Housing Density as a Climate Lever with Scott Wiener

Guests

Scott Wiener

Jennifer Hernandez

Ben Bartlett

Summary

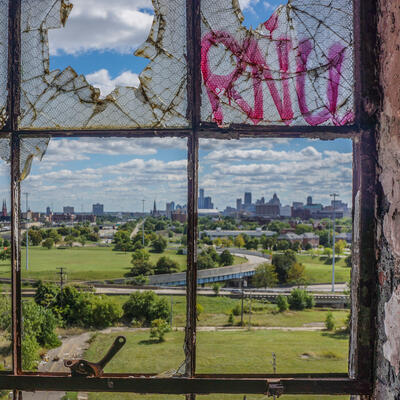

The lack of affordable housing in the U.S. has contributed to a homelessness crisis and has forced people to move farther away from urban centers. Inevitably, that increases car travel and emissions. Yet building multi-story apartments in urban cores usually costs more per square foot than one or two-story houses where land is cheaper.

California State Senator Scott Wiener, a driving force behind the housing density and zoning conversation in the Golden State, says, “The easiest place to put housing is where there are no neighbors, or very few, which means sprawl, which means destroying open space, destroying sensitive habitat, building in wildfire zones.”

In California, a historic undersupply of housing has led to soaring prices and an increasing number of people without homes. And it’s not just California; cities across the country are facing a housing crisis. Home prices have risen more than 30% over the past few years, and rents are rising sharply too. A lot of cities that once were affordable aren’t anymore. It is estimated that the U.S is 3.8 million homes short of meeting its housing needs.

Infill development could be a solution. That means building in vacant or underutilized land typically in urban areas. It can also mean adding more density to existing single-family home neighborhoods by changing zoning to allow things like accessory dwelling units, more commonly known as guest houses or mother-in-law units.

Changing zoning laws would allow more people to live where there are jobs and infrastructure in place to support them, and reduce the amount of traveling necessary. Wiener says, “Having housing that's located in a place where people don't have to drive everywhere, commute long hours, be close to where they go to school. That's how we really, really reduce our carbon footprint.”

Single family zoning is a vestige of a racist practice known as “red-lining.” Wiener says, “Single-family zoning was invented about 100 years ago after the Supreme Court struck down racial zoning.” This style of zoning actually started in Berkeley, California, as an effort to keep people of color out of the community without explicitly forbidding them from living there. Single family zoning has become the norm in neighborhoods across the country.

Berkeley Vice Mayor Ben Bartlett is working to change that. Bartlett says, “It’s a necessary function if you wanna have a holistic society with your children able to live here and your company able to have workers remain here, you have to expand the portfolio.”

Not everyone believes that infill development is a good idea, though. There are some that don’t like the idea of their communities changing, and have adopted a “not in my back yard” stance, often referred to as NIMBY. Others feel that it doesn’t have to be a binary choice.

Jennifer Hernandez, a lawyer and leader of Holland & Knight's West Coast Land Use and Environmental Group, argues that new construction further away from urban cores can be both more affordable and more environmentally sound: “It's...easier to build new in a way that is entirely sustainable, net zero for greenhouse gas. The most water and energy conserving structures that we know how to build are the current building codes.”

The move to EVs and other low emission vehicles may alleviate some of the climate harms of transportation. Hernandez says, “Housing is very much about respecting and all of the above and all of us strategy.”

Episode Highlights

3:44 State Senator Scott Wiener on housing construction

6:19 Scott Wiener on racist origins of single family zoning

17:28 Scott Wiener on community displacement

25:02 Scott Wiener on The California Environmental Quality Act

30:49 Ben Bartlett on his personal story growing up in Berkeley, California

31:48 Jennifer Hernandez on her family history in Pittsburgh, California

34:31 Ben Bartlett on Berkleley’s not so liberal history

38:08 Jennifer Hernandez on development in California

49:50 Jennifer Hernandez on the “golden rule”

Resources from this Episode (4)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. The lack of affordable housing in the US has contributed to a homelessness crisis and has forced people to move farther away from urban centers.

Scott Wiener: The easiest place to put housing is where there are no neighbors or very few which means sprawl.

Greg Dalton: On the other hand, increasing density where there’s already infrastructure and jobs could be good for both housing prices and the climate.

Scott Wiener: Having housing that's located in a place where people don't have to drive everywhere, commute long hours, be close to where they go to school. That's how we really, really reduce our carbon footprint

Greg Dalton: But building multi-story apartments in urban cores usually costs more per square foot than one or two-story houses where land is cheaper. So how do we address the need for affordable housing and the climate crisis at the same time?

Jennifer Hernandez: We need to build policies around what we can afford, not what each special interest decides they want.

Greg Dalton: Housing Density as a Climate Lever. Up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious.

Female Speaker: Stand up for your property right before they get taken away! They wanna take away your decision of where you’re gonna live and how you’re gonna live!

Male Speaker: We live here in this community just like they do. And while we respect their position, we’d like them to hear our side of it.

Female Speaker: We’re really clear about the demands that we’re making. We want a hundred percent affordable housing.

Female Speaker: In those 40 bedrooms there could be as many as 80 people. And if even 20 of them have cars it will be a nightmare for this neighborhood.

Male Speaker: We want to be a city that includes Latinos, includes African-Americans, that includes seniors, that includes people who have limited income. We do not want to be a city that is just overtaken by the highest bidder. But that is what the city is becoming.

Male Speaker: One of the guys that I work with currently, he commutes from Tracy. And he says that he starts his shift at 6:30 but he leaves his house at 3:00.

Male Speaker: We do not want to put the lives of our citizens at risk to what I would call ill-advised, multiunit, high-density units.

Greg Dalton: Wow. In that news montage I hear fear of traffic, fear of displacement, and a racial dog whistle about ill-advised density bringing in others. And yet in California a historic undersupply of housing has led to soaring prices and an increasing number of people without homes.

Ariana Brocious: And it’s not just California, we’re facing a housing crisis nationwide. Home prices have risen more than 30% over the past few years, and rents are rising sharply too. A lot of cities that once were affordable aren’t anymore. It is estimated that we’re 3.8 million homes short of meeting our housing needs.

Greg Dalton: That’s a big deficit.

Ariana Brocious: One proposed solution is infill development. This is building in vacant or underutilized land typically in urban areas. It can also mean adding more density to existing single-family home neighborhoods by changing zoning to allow things like accessory dwelling units, more commonly known as guest houses or maybe mother-in-law units. Increased density tends to decrease reliance on cars and thus cut carbon footprints.

Greg Dalton: Right. When most people think about housing and climate, they may think about replacing gas furnaces and stoves with heat pumps and induction cooktops. That’s all good. And transportation is a bigger lever. To find out how we might help mitigate both the housing and greenhouse gas crises, I talked with California State Senator Scott Weiner. He’s the guy making this conversation happen in the Golden state. And I asked him how he sees new housing construction as a climate lever.

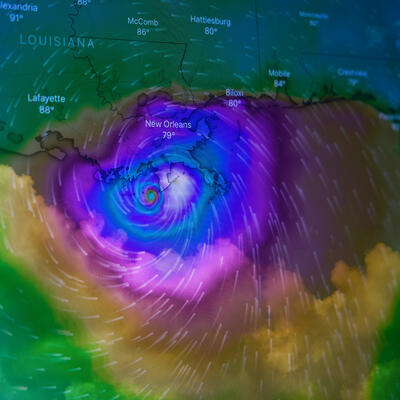

Scott Wiener: I mean of course we want all of our buildings and particularly new ones to be decarbonized and to have a lower carbon footprint and of themselves, it's very important. But even more important is having housing that's located in a place where people don't have to drive everywhere, commute long hours where people can drive less or if they choose not drive at all have access to public transportation, be close to where they go to school where they work, go to the gym and so forth. That's how we really, really reduce our carbon footprint because transportation is a massive aspect of carbon emissions, in California it’s almost half. And so, if we’re serious about reducing carbon emissions we got to have a more sustainable land-use patterns in terms of where we’re putting housing.

Greg Dalton: Right. And most of the curves in California on climate are going in a positive direction down if they’re bad things and vehicle miles traveled is the one thing that’s getting away from California.

Scott Wiener: Absolutely. We’re not doing enough personal to support public transportation because we make it so hard to get housing approved in the places where we want it. An infill housing near jobs near transit in existing communities we make it so hard and expensive, The easiest place to put housing is where there are no neighbors or very few which means sprawl, which means destroying open space destroying sensitive habitat building in wildfire zones building further and further and further out where there are fewer people to complain about the housing and that is very destructive environmentally.

Greg Dalton: Two thirds of residential land in California had been restricted to single-family homes that have been off-limits to the development of backyard houses. A law you authored changed that yet it hasn't opened up a whole lot of new supplies. So, why is it so hard to build affordable housing in the world's fifth largest economy?

Scott Wiener: Well, in terms of zoning you're right the large majority of land in California was zoned only for single-family homes. And what that means is to put in totally planning means every other kind of housing was banned. Didn’t used to be that way until like 50 years ago, you could build apartment buildings in a lot of different places. And then starting in the 70s into the 80s cities methodically banned apartment buildings and set only single-family homes. So, only one unit of housing per parcel which creates a math problem. And it also completely induced sprawl and people knew at the time.

Greg Dalton: And racial filtering, let’s be honest.

Scott Wiener: Single-family zoning was invented about 100 years ago after the Supreme Court struck down racial zoning. Communities starting with Berkeley discovered well we can’t explicitly ban people of color, but what we can do is make it impossible for anyone who's not upper income to live here and so they said you can only build single-family homes. So, we did pass, well first, we really strengthened their existing law to allow for in-law units or what we call an accessory dwelling unit. And that it took a while but that's now exploding. We’re seeing it up and down the state these accessory units are being built in increasing numbers. A couple years ago we passed legislation led by our Senate President Senator Toni Atkins from San Diego to basically eliminate single-family zoning and to have duplex zoning or 2 to 4 units. It’s only been in effect for a year, you know, development never moves as fast as we want so people are worrying that it’s not producing enough, but it'll get there it; just takes time.

Greg Dalton: Okay. So, granny units or in-law units, we’ll get there. Yet when it’s still cheaper to build outside of cities further from jobs and amenities how do you address climate and the justice and equity issues at the same time?

Scott Wiener: Well, we need to make it easier and easier to build in sustainable locations infill housing, in existing communities near jobs near schools near public transportation. And that's what we’re trying to do to try to because right now we’ve set up a system that's designed to fail. A system that empowers, I’m a former local-elected official. I'm a former neighborhood association president, I believe in public input and people having a stake in their own community and having the right to have an opinion about their own community. But we've gone so far beyond that, that we have endless process that can take years and years and years, even if you're building within all the rules. In addition, we have empowered obstructionists who are not typically representative, right, most don’t even know that this public hearing is happening. They’re working and they’re trying to get their kids to do their homework. They're putting dinner on the table. And you have people who may or may not be representative of the community at large. But they have the ability to show up in a million community meetings and to file appeals and we've given them the tools to obstruct, delay, kill these projects and that needs to change.

Greg Dalton: Some people say that housing is an example where NIMBYs and progressive areas have captured regulators. Something that liberals often accuse people on the right and corporations of doing. But NIMBYism for the regulatory capture from the left. So, what’s the solution?

Scott Wiener: Well, first of all I don't think NIMBYism is left. True progressivism is not NIMBYism. And so, I think you have people in the blue areas like parts of California and other parts of the country who have they might have a Bernie Sanders sign on the lawn or Black Lives Matter sign on their lawn or a big rainbow flag unfurled which was great. But they are at the same time acting in a very, very conservative way by saying I don't want any change in my community. I'm worried about the "kind of people" who are gonna come here who are gonna somehow "degrade" my community. If showing up at a planning commission or a city council like development appeal in a blue area sometimes it doesn't sound that different from a red area in terms of the things that come out of people's mouths. And things that it's shocking to hear people say and I get it people were very passionate about their neighborhood I completely respect that but sometimes we need to be forward thinking in saying hey this might maybe it’ll be a little bit harder for me to park. Maybe there'll be a view that I've had for a long time that isn't quite as good anymore. But more people are gonna be able to live here, that there will be a prayer for the next generation to have a place to live. Maybe fewer people will be living in their cars. Maybe we won't have 5% of San Francisco Unified School District 5% of those kids are homeless and that's consistent and probably an undercount statewide. That we have families who are literally waking up in a homeless shelter or a car dropping their kids off at school going to work. And so, that's what this is about. And so, I think NIMBYism is inherently very conservative, even if you're registered as a Democrat.

Greg Dalton: California has a statewide goal of reaching 2 1/2 million new housing units by 2030 one million of which was must be affordable. New housing construction has fallen behind demand for decades. And for decades cities and counties have not met their goals and not much has happened. Now those jurisdictions face financial penalties for not meeting state-mandated levels of new housing. Will the hammer get the job done?

Scott Wiener: I think it will move us in a very good direction. And we see what's happening in the last six or eight years where we've really been putting teeth into long-standing state housing law in California and passing new laws and it has, I think it’s gradually working. And we look at in San Francisco the Board of Supervisors just adopted what we call housing element. And a housing element in California is every eight years, a city has to put the other housing plan incorporating like numbers of new homes that the state provides. And you have to plan for how you’re gonna meet those housing goals in the next eight years. And historically, the process has been a sort of a joke. I went through, I was in the Board of Supervisors it was very controversial, but ultimately, it's like a document that sits on a shelf collecting dust. The housing element process now has teeth in it, and San Francisco just adopted a new housing element to plan for 82,000 homes. So, a very, very strong plan. I want to commend their planning department and the Board of Supervisors and the mayor and everyone who made this happen. But that happened because the people and our city government who want to do the right thing now have the leverage to do it because the hammer of state law was out there. That if the city adopted a bad housing plan or didn't adopt one on time there’ll be all sorts of consequences and cities up and down the state are seeing that and a lot of them are trying to do the right things. And the ones that don't do the right thing are gonna have consequences.

Greg Dalton: And so, that's 2 to 3 times the amount of annual production that San Francisco and Bay Area –

Scott Wiener: Three times.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, three times. So, is that gonna make the NIMBYs not be NIMBYs?

Scott Wiener: No. What we found is that even when you streamline housing approvals and if there are cities that want to fight it, they’ll try to find loopholes with in-law units for years, cities were technically required to allow people to put in-law units in their homes. Cities ignored it. They found all sorts of loopholes. We eventually it took us like five or six laws that we passed. We finally I think sealed off every loophole and now it just sort of happening. And unfortunately, and there are certain cities that have showed us the way like they’ve been so obstructionist that they unearth every loophole which I really appreciate – Cupertino did a great job with that where Apple is headquartered. They unearth every loophole and so we will close the loopholes based on what they discovered. And they now have a new city council that's a lot better so that's a good thing.

Greg Dalton: Transit oriented development has been talked about for a long time aims to build housing near transportation hubs. I recently drove around near the BART station in Concord, a city of 130,000 people, 30 miles from San Francisco. There are empty lots near the regional commuter rail station, also blocks of housing 4 to 5 stories tall. It’s like, okay, I can see kind of things happening here. Yet, building on parking lots near that commuter rail is highly controversial. Some say how housing is a higher use of that land and others say removing parking hurts working-class people who can't afford to live close by because housing prices are so high. So, how do you balance that?

Scott Wiener: Yeah, I mean if you think about it when you look at like the BART system in the Bay Area. We have all these BART stations. We made public investments and very few people live within walking distance. It's people who live in single-family homes who are privileged to have been able to afford those homes right by the BART station. And so, the idea is to also allow for apartment buildings, particularly BART has a lot of land around the stations to put apartment buildings. And we actually a few years ago, we passed a law authorizing BART to approve its own projects within certain constraints. It was very controversial. We felt that it was important because some of the cities that have BART stations were just refusing to allow it. We want to make sure that these are mixed income developments that some will be hundred percent affordable, or mixed income with market rate and below-market rate mixed together which is great to have mixed income developments. We want to make sure that people of all incomes can live there. There’s also nothing that would stop BART instead of having if you think about it these massive parking lots that surface parking lots. If you replace that most of it for housing you can still have, they can create a parking structure. If they want there’s nothing stopping them from doing that so the people who are, you know, still the ability to drive in if they don't live anywhere nearby. So, there's nothing stopping BART from having that kind of mixed use.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about housing density as a climate lever. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Coming up, how can more vulnerable communities be protected against displacement from development in their neighborhoods?

Scott Wiener: If you combine anti-displacement strategies with adding new housing you're not going to see that kind of displacement. You will reduce the pressure because you have all these new buildings that people can live in without having to try to displace people and other older buildings.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

Displacement is also a huge part of the housing crisis for low income communities and communities of color. New housing often follows upscale shops and eateries. Together they can drive up prices in neighborhoods that were once affordable and force the existing community out.

Let’s continue my conversation with California State Senator Scott Weiner. I asked him how we can make sure new development doesn't increase displacement.

Scott Wiener: I think that we have to be very clear that the cause of displacement is not having enough homes. When you have a shortage of homes there's competition and the prices go up. And we know what happens and we know who tends to be the winners and who tends to be the losers. And lower income working-class people tend to draw the short end of the straw when you have a shortage of homes. And so, for example about nine years ago we had a big fight about whether to have a moratorium on new housing in the Mission. And there were advocates in the Mission who are pushing for that because they’re very concerned the new construction was going to push out –

Greg Dalton: This is a historically Hispanic part of San Francisco.

Scott Wiener: Yeah. And what they pointed to correctly was over the last prior 10 or 15 years something like 8,000 Latino families had left the Mission. And while some of those families no doubt left because they maybe bought a home in the Excelsior or went to another city there are clearly a significant number of Latino families that have been pushed out of the Mission. But if you look at housing construction over that same, I forget, 10- or 15-year time period, almost no new housing has been built in the Mission. If you rank San Francisco neighborhoods for that time period the Mission was very close to the bottom in housing production. That's changed over the last decade, but at that time we were seeing massive displacement in the Mission with almost no new housing being built. And that is because the Mission is an amazing neighborhood. It is central it’s great weather it has good transit. It is a beautiful wonderful neighborhood. And a lot of people wanted to live there. And that jacked up the rents and it gave landlords incentives to evict people and all that. And so, having a shortage of housing is the core driver of displacement. You can have a bad situation where you allow for new housing where you're demolishing old housing and displacing people. And that's why new development needs to be accompanied by anti-displacement strategies like not knocking down apartment buildings where people are living just to replace it. And in the narrow circumstances where it does make sense to replace a building taking care of the people who are there by giving them temporary housing and then bringing them back paying the same rent which we've done in some developments. We need strong renter protections so people aren't evicted. So, if you combine anti-displacement strategies with adding new housing you're not going to see that kind of displacement. You will reduce the pressure because you have all these new buildings that people can live in without having to try to displace people and other older buildings.

Greg Dalton: So, there’s often a formula that new construction has to be what 30% affordable; is that enough?

Scott Wiener: First of all, you need projects to be able to pencil out. So, we have publicly funded projects that are typically 100% affordable where we use tax credits and bond financing, and so forth. When you’re talking about private development, San Francisco's inclusionary the required affordability is like 20 or so 21%. And, you know, different kinds of projects pencil in different ways. There are some smaller projects where 21% may not be feasible for that project. Larger projects, especially projects that also maybe include office or other economic drivers can probably support a higher percentage of affordability. And so, we want to make sure we have these mixed-income projects. But we also need to make sure they pencil out financially because you can have you can say we want 30 or 40 or 50% affordability. But if the project doesn't pencil out 50% of zero is still zero.

Greg Dalton: Right. Still has to attract capital to do that project. Because even the state doesn't have enough money to build all of this yet we’re still talking about what million dollars a door. I mean is it really ever gonna really make build enough housing when it's so bloody expensive.

Scott Wiener: Yeah. The cost of construction is off the charts. And it’s higher in San Francisco now. So, it’s going to be higher I mean it’s more expensive to do anything in a place like San Francisco or New York City, you know, big cities. But it’s way, way, way too expensive and --

Greg Dalton: How do we get it down?

Scott Wiener: Well, the process costs adds to that. If it takes 3, 4, 5, 7 years to get something approved instead of like 3 to 6 months which some of the laws that we've been able to pass that streamline permits say that the city has to give the permit within 3 to 6 months depending on the size of the project. So, for example I’ll tell you, BRIDGE Housing which is the largest nonprofit affordable housing builder in California told us that after a particular law that I authored was signed into law SB 35. Once that happened their average time to get a permit to build dropped from an average of seven years, to an average of four months.

Greg Dalton: Wow.

Scott Wiener: And so, when you think about it if you have a project that goes on and on that is dragging on appeals and lawsuits and endless process. You think about all the architects and the lawyers and the consultants and everything that is very expensive and adds to the cost. We have a construction workforce shortage in California that drives up the cost. We want to make sure we need to train more construction workers. We have much less control over the cost of materials and we know that construction materials have gone up in the last few years, but it is way too expensive and it is a problem.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, prior to the pandemic office vacancy rates in San Francisco was about 4% today it’s around 26. Nationally, that number is about 12%. Can cities in California around the country convert some of those empty offices to residential?

Scott Wiener: Last year we passed legislation that facilitates commercial conversion. And that typically is gonna be, you know, strip malls or office parks or sort of low-rise. When we talk about downtown San Francisco, converting high-rises to housing is very hard. And it can be very cost prohibitive because if you think about how the plumbing for example, it's very centralized like one bathroom per floor. So, you have to completely restructure the whole building. It could work for some highrises, but for many it won't be feasible. I also just want to say and this is just in defense of the great city of San Francisco. Our obituary has been written a million times. And every time we come back stronger than before downtown is obviously going through challenging times. It is more vibrant now than it was six or nine months ago. The owners of the Transamerica Pyramid are making a massive investment in that building. And I think downtown San Francisco will come back. And what I don't want to see is cannibalizing our office stock and then all of a sudden we’re back where we were in 2019, where we had a massive shortage of offices and small businesses and nonprofits, and law firms, etc. were getting push out of the city because there was no office space they could afford. So, I want us to take the long view. I don't think anyone knows what offices gonna look like in three years. Anyone who says they does I think they’re speculating. So, I think we need to be very thoughtful about how we approach that.

Greg Dalton: Environmental regulations like California Environmental Quality Act, the National Environmental Policy Act often used to slow down they’ve been weaponized. Should they be reformed or relaxed in some way?

Scott Wiener: Yeah, massively. The California Environmental Quality Act is I referred to it as the law that swallowed California. This is a law that was created in 1970 for excellent reasons. And I’m not one to say CEQA should be repealed. CEQA needs to be refocused on actually protecting the environment. And CEQA needs to be turned into a climate action law, which right now it is not. The purpose of CEQA was when you're doing something that could be potentially environmentally destructive building a highway building a dam doing something that could be really harmful environmentally that you have to analyze environmental impacts to inform the decision-maker. That's a great idea. CEQA was never intended to allow your neighbor to jack you up because you're trying to replace your windows. And right now, you can do that --

Greg Dalton: Or stop a bike lane.

Scott Wiener: Stop a bike lane stop a bus rapid transit lane. Stop an apartment building on top of the public transport on top of a rail station. That some of the things CEQA is being used for or to stop UC Berkeley from admitting students that's what a court decision ruled last year before the legislature overruled the court and change the law. And so, when you look at some of the things that or to stop solar it’s used for that too. And so, that is a problem. CEQA converted from environmental law to a process law. And I'm not saying there are times when CEQA can be used to stop really bad projects, but there are a lot of good projects that either get killed or delayed and become more expensive or get chopped in half. And anyone who can hire a lawyer, you can be a CEQA player and you can delay and stop projects. And that is government at its absolute worst. It's not democratic.

Greg Dalton: Again, CEQA is the California Environmental Quality Act. What housing and city models do you look at elsewhere, who's getting it right? You're an expert on housing here in California. Look around the country, what do you see that's real bright spot?

Scott Wiener: Well, I think there are cities that the rents and this is pre pandemic the pandemic scrambled things up a bit that built a lot of housing and rents came down. Like Washington DC was one Chicago was another. I’m not saying they have perfect systems but is show and these are great amazing cities. I'm a believer in social housing which we used to call public housing publicly built and run housing typically mixed income. And we used to do that, Ronald Reagan killed it off in the 80s, which is by the way when homelessness started to skyrocket. That was not a coincidence. We need to get back to significant public investment in social housing. So, a group of us went to Vienna last September and they have an amazing social housing system, but other European cities do as well as well as Singapore and it's a really great model. It doesn't have to be the entire housing system, it's not about taking people's homes away, but it should be there as a bedrock really just to make sure that everyone has a home and can afford a home. That should never be a question in a society, but whether someone has the ability to have a home. Having a home should never be a privilege, it should be a right. But it can only be a right if we have enough homes for everyone who needs them.

Greg Dalton: Even Hong Kong, one the most capitalistic places on the planet, has a lot of public or social housing. For how long can the California ecosystem continue to support population growth?

Scott Wiener: You know, I don't agree that building new housing is what drives population growth. People move where they want to live.

Greg Dalton: But the lack of it can drive people out of state.

Scott Wiener: It can, but let’s figure out we stopped building housing in a meaningful way, decades ago. And our population for decades continued to grow. And what that meant was we have more homelessness. We have more overcrowding in homes. And so, I just don't agree that if we stop building housing it's going to just people are gonna stop coming here. They’re gonna still come here. And even though we have in the last few years, California's population growth has plateaued and then shrunk by a tiny amount. I don't know that's gonna continue.

Greg Dalton: We’ve been discussing housing as a climate lever with State Senator Scott Weiner. Thank you, Senator, for coming here and for your leadership on so many climate issues.

Scott Wiener: Thank you.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about home construction in a climate crisis. This is Climate One. Coming up, what effect might generational divides have on addressing the housing crisis?

Ben Bartlett: That generation is spending untold money to private equity and investment to buy up every single-family house in the country. They want to make the whole population below them into subscribers and not owners. So, this is economic warfare.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

Talking about housing supply and prices can be fraught. To discuss the best solutions for the housing crisis in an equitable and climate conscious way, I had a conversation with Jennifer Hernandez, a lawyer and leader of Holland & Knight's West Coast Land Use and Environmental Group, and Ben Bartlett, the Vice Mayor of Berkeley, California, which hasn’t always been as liberal as it is today.

Ben started by sharing his story.

Ben Bartlett: I was living my life as a normal young person in Berkeley having fun. And then all of a sudden, my mother and her friends live in a house they’re a bunch of seniors, retired schoolteachers, they were all victimized by their landlord, who was prepping the building for development. And so, they turn the water off the heat off. It was a very intense situation of economic eviction. They damage their cars all these I read about the horror stories. And when they left, I was like okay, we'll just have and go to senior housing. And then I saw there was no senior housing. The wait list for senior housing I was told was 14 to 17 years. And I didn't quite understand it, I was like, wait, this is America, right? These are taxpayers, they've done their duty and now there’s nowhere for them to go. So, at that moment I realized that there was a thing called a housing crisis and there’s also an economic crisis and a crisis of disrespect of our people. So, I decided to get involved in addressing these issues.

Greg Dalton: Jennifer, your father and I believe both of your grandfathers were steelworkers in Pittsburgh, California where you grew up. How did your upbringing shape your understanding of the relationship between jobs and housing?

Jennifer Hernandez: Sure. So, we had fathers, grandfathers, everybody in town mostly had good union jobs. And one of the things that that came with in America was the opportunity to buy a small home. And that small home became a piggy bank because every month, paying even a modest amount of mortgage I was paying in part to your own family's equity. And the housing crisis really hit first for both grandmothers who spent each almost 20 years as widows with no income. And then for my dad who was laid off permanently from his job at age 56. It was the fact that they own their house outright that allowed my sister to stay in college, my younger sister and ultimately has provided for their old age. That's the American dream. Homeownership was affordable in Pittsburgh. Our family could've never afforded to live in Berkeley. There are different levels of affordability. And for me housing is very much about respecting and all of the above and all of us strategy. And all of us isn't necessarily gonna entice a construction worker which we need more of to be content living in someone else's backyard cottage. and any effort to make one-size-fits-all leaves out people like my dad and my grandparents and my brother and my nephew who are still in the trays. So, it's time to be respectful and that's respectful of both economic and color lines.

Greg Dalton: Ben, Berkeley was one of the first cities to implement single-family zoning shortly after the US Supreme Court struck down racial zoning as unconstitutional. They just rebranded it. Now Berkeley's housing element or housing plan commits the famously liberal city to address its historic underinvestment in communities of color. Will that really happen?

Ben Bartlett: Yes. It will. And it’s important to realize that housing is the fulcrum of the economic health of society. Because you can live in high resource areas your house itself can become a source of wealth and there are good schools and good jobs nearby. So, in Berkeley we, of course, the home of single-family zoning or exclusionary zoning or race zoning as I call it.

Greg Dalton: Which is kind of shocking for a city that’s known and free so liberal. It was new to me we’re learning from you.

Ben Bartlett: Well, there’s a reason why Berkeley is home of the counter cultures because they're reacting to the dominant paradigm at the time, which was hard Corley conservatism. So, the Berkeley radicals were abutting up against the power structure. And that structure still exists as we heard earlier, they are landowners, they may be liberal in politics, but they are still the landowning elite and it’s land hoarding as we were talking about here. So, when you have a timeframe where you have extreme wealth inequality and we talk about people hoarding wealth you think of stocks and bonds money but really land as wealth. And when one group of people has all the land and you see the result, the cascading poverty throughout the city of California and the country and the world you have to address it. So, in Berkeley we're also the home of the Fair Housing Act which addressed the same issues in the 60s and 70s. And so, now we have this buttress to really change all the zoning and allow people who have smaller apartments and duplex and things in wealthy areas and therefore achieve hopefully and I believe it will economic and race diversity in these high resource neighborhoods.

Greg Dalton: But when you say duplexes and density in wealthy areas, they hear black people they hear color, right? That’s code for like, oh, right?

Ben Bartlett: Oh, yeah.

Greg Dalton: So, are those wealthy areas in Berkeley gonna accept more density when they somewhere whether they acknowledge it or not that means scary people.

Ben Bartlett: Well, look, here’s the thing. The generation below mine, the millennials, is the largest generation in human history. They dwarf the baby boomers and they are out here because the older generation above them has not expanded the portfolio of infrastructure from housing, education, health, where you see the student loans out of control the healthcare the housing even arable land, even food. And so, all across the world you have a crisis of affordable housing in every county in the country and also around the world and homelessness now. I was in a meeting with some Republicans in Missouri who asked me for advice about the fact they had 250 homes encampments in their suburb of Kansas City. So, it’s everywhere. So, this is a matter of survival of the economy. You can have that many people at the gates, but you will not stay in the castle very long. So, it’s a necessary function if you wanna have a holistic society with your children able to live here and your company able to have workers remain here you have to expand the portfolio. And also, there’s the economic lesson here as well. As people get older their physical imprint shrinks but their house is still big. And we know that senior care is super expensive so a better way for them is to downsize the house keep a portion of it to live in and make money off the rest by opening up to other people. So, there’s an economic incentive that I think could be persuasive in the end.

Greg Dalton: Jennifer, your thoughts on the sort of the class and race part of this. Because what I hear what Ben is saying a little bit is boomers haven't done so well in what they’re leaving behind. I did a whole interview once about how boomers are kind of sociopaths. They started off as, you know, some of the most liberal progressives in Berkeley, right, gonna save the world, hippies, and they became some of the greediest people around. So, your take on that.

Jennifer Hernandez: Yeah, So, I am a boomer and I'm at the bottom edge which means we got educated about drugs to do and not do which was a benefit, right, other people learned about it. And certainly, from Pittsburgh I owe my scholarships to Harvard and Stanford to those who came before in the civil rights movement and in the kind of counterculture and women's rights movements.California, according to Air Resources Board development is 6% of our 100-million-acre state. Other states that have any kind of normal population,are about 10 to 12% developed. New Jersey is 35% developed. It's everyone knows easier to build new in a way that is entirely sustainable, net zero for greenhouse gas, the most water and energy conserving structures that we know how to build are the current building codes.The idea that climate change means we have to reject the 7% solution a million new acres, even in California built on existing infrastructure designed to be sustainable absolutely walkable. That is a conceit held here as dogma in the name of the environment and it's another baby boomer mistake.

Greg Dalton: But help me understand where that's gonna be because there’s something called the wildland urban interface, which is a lot of places like Paradise, California places up against the foothills wooded beautiful that with our new climate reality are fire zones. And some people say we shouldn't be building there and even the people that shouldn’t rebuild there. So, if we’re gonna spread out further isn’t that going right into the fire zone and danger zone, when we go up against the Sierra foothills, where is this gonna happen?

Jennifer Hernandez: So,you skipped a few places in order to get to the Sierras. A lot of Marin right now is being used to grace cows which have their own greenhouse gas emission profile. Adding 50,000 people to Marin is a heck of a lot better for the climate than grazing cows. But it's an aesthetic that we won’t add people to Marin. It’s a baby boomer prejudice and it’s not about the environment.

Greg Dalton: It’s also racial prejudice.

Jennifer Hernandez: I completely agree with you there. I wrote a piece called Green Jim Crow about the use of environmental law to promote racism.

Greg Dalton: Ben, what do you think would you rather have, this is not easy or binary maybe it’s, and but the trade up between more densely populated in cities like Berkeley or building out.

Ben Bartlett: It’s both. I mean we need the whole portfolio. And you make excellent points too, I got to say. So, we need the urban centers of course, because that's where the most heightened human activity is in the world. That's where the healthiest, wealthiest, most opportunities, it’s the place.

Greg Dalton: And low carbon footprint.

Ben Bartlett: And low carbon footprint, of course. And a place that traditionally people of a non-majority status have done well. And then we also need to expand elsewhere as well because I mean looking at the state, we have more than 100,000 homeless people. We have a burgeoning workforce that is leaving the state and we have so many people commuting so far, living in their cars we’ve got to address the whole panoply.

Greg Dalton: And you describe what's happening in desirable neighborhoods as intergenerational warfare, how so?

Ben Bartlett: You know, this movie Tenet, a sci-fi film came out recently. It’s a very talky movie, but there's a line in there which sticks out. It's when the main character is asked why do you think the people in the future are trying to kill us? Because they’re at war at the future. And he says, well, that's how it is its every generation out for themselves. So, you know, right now we are all at least my generation below are in a defensive trench hold position fending off attacks from the older generation. And for instance, my old boss went to law school. I think he paid $15,000, right, you won’t even know what my student loans are, multiple six figures. Everything that they got what they get was good they locked up and kept for themselves. It's almost like the 10 families that owned some third world country. We’re replicating that we’re this one percent as we call it basically a different kind of number. It controls all the resources it makes you fight to death to get your share of it. Case in point, California is 49 out of 50 for homeownership. That's ridiculous. And at the same time that generation is spending untold money to private equity and investment to buy up every single-family house in the country. They want to make the whole population below them into subscribers and not owners. So, this is economic warfare.

Greg Dalton: And owning a house is the way that most certainly since World War II the biggest source of family wealth, the biggest way that families accumulate wealth. So, you're saying that it's concentration more and more on top and the people are gonna be subscribers and never owners.

Ben Bartlett: Right. And the trends involving artificial intelligence, decimating white-collar work, so on, automated train stations coming as well. So, the complete decimation of the transportation sector job wise. So, you have this dystopian future that they are dedicated to making it happen where most of us are surviving on pennies paying rent owning nothing and liking it.

Greg Dalton: And you’re saying it’s been blue-collar displacement, the white-collar people you’re not safe anymore.

Ben Bartlett: Right. They’re not safe at all. They're done. If you've used ChatGPT you see it coming. The next four years in our immediate lifetime you’ll begin to see the economic system began to unravel. So, we’re in it right now. And so, for me this is about as existential because my family we escape slavery. And, you know, our motto is never again. And these conditions that housing again being the fulcrum on is setting the stage for return to servitude and it’s not acceptable so we have to join this fight.

Jennifer Hernandez: Yeah. So, I think that you've open my eyes to still more badness.

Ben Bartlett: Thank you, Ben, for coming.

Jennifer Hernandez: But, you know, while all you youngsters have been suffering out of sight for my generation, we've been chasing gremlins. There's a law professor who calls procedural perfectionism a new value that has overwhelmed all other values. So, CEQA is about the California Environmental Quality Act is about procedural perfection. Have you studied everything including stuff we don't even know we have to study to the ends to greet the satisfaction of a 62-year-old judge, who majored in social studies and is a conservative white homeowner? And if not, go back and do it again. But you wonder about your million-dollar per door cost and its value-based decisions, standard base decisions and process based over legalism. That has created a policy suite in California that isn’t replicated even in the rest of the country. It’s choices we've made and we need to be bolder about working together across the generational lines to break it down.

Greg Dalton: So, Jennifer, what's the solution?

Jennifer Hernandez: It’s totally simple. We need to join the rest of America in designing and regulating homes to four times median income. It's a magic number. If your median priced home is no more than four times your median income of households, you have a healthy housing market. And the median income changes depending on where you are in California, but it's roughly 80 to $120,000. Californians make a lot more than most country. But we need to build policies around what we can afford not what each special interest decides they want and has enough political clout to enforce.

Greg Dalton: We know that California's vehicle miles traveled is one carbon metric that's going the wrong direction. Most of California is climate --

Jennifer Hernandez: I'm sorry I completely disagree. It’s not a carbon metric. We’re doing EV vehicles. We went from less than 5 miles per gallon when I grow up to now more than 50 miles a gallon in a hybrid vehicle that can go as long a distance as a regular car. And we’re moving to EV vehicles. Transportation does not equate to terrible climate outcomes, transportation –

Greg Dalton: The biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the state. So, Ben, how are you doing here in between two bougie boomers, you know.

Ben Bartlett: You know, I’m good I’m feeling it, I’m feeling it. Because, you know, I said this before at council again, you know, and I work in innovation on my day job it’s like I kind of pulse what’s coming. So, the whole notion of commuting is gonna be altered by basically these robotic cars that sort of into our neighborhoods. Those people cruising all the time those share a car people, oh you want to drive. The cars will be electric and hydrogen.

Greg Dalton: Sounds like a dystopian hell of traffic jam.

Ben Bartlett: Well, that part will be fun because there’ll be in sync,

Greg Dalton: So, Jennifer, what about the areas that are already urbanized with commercial to have a little more housing there? There's already traffic transit perhaps, isn’t that part of the solution?

Jennifer Hernandez: Well, it's been part of the solution and zoned as part of the solution now for more than a decade. We already have a number of streamlining laws on the books that we do some of the hurdles to getting that developed. There’s just a little problem which is the pro forma, the actual budget. Because those properties, especially in a high wealth community like Silicon Valley are earning a lot of income. And when you think about buying them you need to buy them at a price which makes sense for the owners who are gonna give up that income stream. And then you have to put million dollars per apartment buildings on them and hope that you can find enough now in that case, probably $8000 a month renters. Because we’re not buying or building anything at scale at homeownership; it's all rental apartments. And so, the fact is, and that's before you add the 20% inclusionary for mixed income. The fact is, those projects haven't penciled. If they did, they'd be being built.

Greg Dalton: Ben,you seem to be questioning capitalism the kind of private equity buying up homes the kind of hyper capitalism, which is very different let's be honest. Hyper capitalism today isn't serving us well.

Ben Bartlett: Well, it’s actually like hyper financialism. It is the Wall Streetfication of stuff. Because capitalism is neutral it’s like electricity, it can heat your home or it can fry you in an electric chair, right. Electricity is power. Capitalism is a very efficient means of harnessing human power and it drives innovation, it drives cooperation, it pushes excellence and increases growth. And there’s no question that American capitalism at least are American form of moneynomix has led to the greatest prosperity in human history for most of the world too. And every year it gets better than before. So, I do think like everything else, capitalism needs to constantly be modulated and caused to challenge itself caused to grow because right now our ecosystem is on the verge of collapse. They’re saying that we’re gonna lose half of all species the next 40 years. So, we need to just, put new incentives here so we can put our energies into something that will cause benefit to the world.

Greg Dalton: So, Jennifer, balancing capitalism and environment and human nature.

Jennifer Hernandez: You know there's that whole golden rule thing. It’s simple stupid. It works for me. I think it actually works more broadly. And it has been an underpinning of American capitalism before it became Wall Streetification, I love that phrase, because the idea that you could do financial manipulations at a level that brings down the global economy by playing around the secondary mortgage markets. That's not inherent in capitalism. Capitalism is working hard, being able to save money buy a house, raise your kids and hopefully have the next generation do better than you are. So, a little bit of return of the golden rule and frankly of civil rights. We’ve managed to park civil rights underneath some weird environmental justice only prioritization which is an important part of civil rights. But what about upward mobility. What about equal opportunity. What about respect for people who didn't go to college and don't work on a keyboard that do work with their hands that we rely on every day.

Greg Dalton: And we need a lot of those people to electrify things and we need a lot of electricians in this country in the state that we don't have people that work with their hands.

Jennifer Hernandez: And where are they gonna live? So, it comes to housing is the fulcrum. I like that a lot.

Greg Dalton: Back to Pittsburgh and the steelworkers. Ben Bartlett and Jennifer Hernandez. Thank you so much for joining us here on Climate One. Let’s give them a round.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One... We’ve been talking about addressing the housing and climate crises equitably. Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe wherever you get your pods. Talking about climate can be hard-- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Our producers and audio editors are Ariana Brocious and Austin Colón. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager, who co-produced this episode. Our team also includes Sara-Katherine Coxon and Wency Shaida. Our theme music was composed by George Young (and arranged by Matt Willcox). Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.