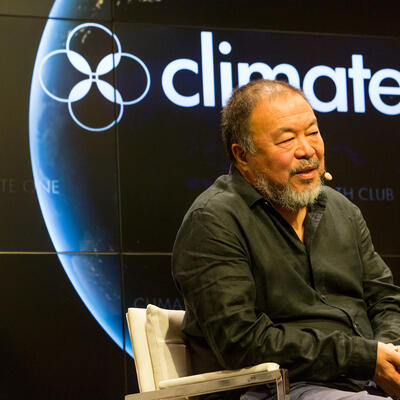

Driving Forces: How Climate Fuels Human Migration

Guests

Paul Salopek

Dina Ionesco

Francesco Femia

Lauren Markham

Oscar Chacón

Summary

Climate instability is an increasing driver of human migration. But no one identifies themselves as a climate refugee.

“The Geneva Convention does not provide for persecution by climate change,” says Dina Ionesco, head of the Migration, Environment, and Climate Change Division at the U.N. Migration Agency. “It's something that talks to our spirits, to our hearts. But you can’t have the status of a climate refugee today in our world.”

Yet even with erratic weather, extended droughts, and resource scarcity fueling political conflict and pressures on vulnerable rural livelihoods, Ionesco doesn’t believe that reopening the 1951 Refugee Convention is necessarily the best way to address the issue.

“First, a lot of this migration is internal,” she explains. “People are not crossing borders, they are not asking for third country protection, which is what defines in fact that refugee protection. And second of all… it’s very difficult to isolate climate change and environmental drivers from the other drivers.”

Oscar Chacon, co-founder and executive director of Alianza Americas, agrees that causes of migration need to be addressed at their source first.

“I think that there is still work to be done in countries of origin to actually prepare for the likely event that there will be even more severe changes coming down the pike in terms of climate change,” he says, adding that “changing laws in the U.S. to accommodate the inevitable reality of more people on the move is also part of what should be a much more realistic understanding and practice of shared international responsibility.”

Lauren Markham, a writer reporting on youth, migration and the environment, observed some of the root causes of climate migration after spending time in southern Guatemala.

“[The] relationship between poverty and gangs is huge and climate change in countries that are highly agrarian,” she notes. “Climate change is only leaving fewer options for farmers and fewer opportunities for people to lead any kind of realistic subsistence life.”

Related Links:

National Geographic Out of Eden Walk

International Organization for Migration

The Center for Climate and Security

Alianza Americas

The Far Away Brothers: Two Young Migrants and the Making of an American Life

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One, leading the conversation about energy, the economy, and the environment. [pause] Climate change is a global challenge. But international law is still catching up.

Dina Ionesco: The Geneva Convention does not provide for persecution by climate change, that does not exist.

Greg Dalton: As climate instability drives more people from their homes, migration within and across borders is becoming a defining issue.

Francesco Femia: There's a tendency to think well that’s not really happening here we can’t have internally displaced people in the United States can we? But it's happening.

Greg Dalton: How can nations better protect (vulnerable) migrants at home and abroad

Oscar Chacon: I think that there is still work to be done in countries of origin to actually prepare for the likely event that there will be even more severe changes coming down the pike in terms of climate change.

Greg Dalton: How Climate Fuels Human Migration. Up next on Climate One.

---

Greg Dalton: Will climate change turn us into a world of uprooted migrants? Climate One conversations feature energy companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats, the exciting and the scary aspects of the climate challenge. I’m Greg Dalton.

Greg Dalton: Climate instability is an increasing driver of human migration. But no one identifies themselves as a climate refugee.

Dina Ionesco: It’s a notion that doesn't have a legal meaning today. It's something that talks to our spirits to our hearts. But you can’t have a status of a climate refugee today in our world.

Greg Dalton: Dina Ionesco is Head of the Migration, Environment, and Climate Change Division at the U.N. Migration Agency in Geneva. She acknowledges that environmental degradation may be one among many factors driving migration. But people leaving their homelands are even less likely to cite climate as a cause.

Oscar Chacon: People in Central American countries, if you actually ask them why did you feel forced to leave your country, they would not tell you oh because of climate change.

Greg Dalton: Oscar Chacon is co-founder and Executive Director of Alianza Americas, a network of Latin American and Caribbean immigrant organizations in the U.S. Extreme cycles of drought and rain have left many subsistence farmers around the world without any viable options to work and eat.

Lauren Markham: Any place there's a cash crop when that cash crop is decimated there's no fallback plan, right. There's nothing that we can kind of do tomorrow in order to feed our families and to buy our food.

Greg Dalton: Lauren Markham is the author of The Far Away Brothers: Two Young Migrants and the Making of an American Life. We’ll hear from her and others later in today’s show. First, a conversation with a voluntary migrant out to retrace the earliest movements of human populations. In 2013, journalist Paul Salopek began his “Out of Eden” walk -- setting out on foot from the Rift Valley of Ethiopia through the Middle East and across Central Asia. Along the way he’s documenting how current populations are coping with climate change and other challenges.

Paul Salopek: I’m following the pathways of human migration out of Africa back in the Stone Age and using that is kind of my template for talking about current events. And so I picked what an ancient human site about 120 km north of the capital Addis Ababa called Herto Bouri and that is in the Sahel it’s kind of a transition zone between desert and pure desert and kind of grassland savanna. And as I started walking very soon within a week or two started bumping into evidence of other migrants, you know, who were doing their migrations involuntarily very privileged walker. I carry a powerful passport I’m backed by powerful institutions my ethnicity my gender everything I realize I’m very special I’m not typical. But I began encountering other migrants on foot inching their way across this extremely harsh environment on their way to the Gulf of Aden. Why the Gulf of Aden? Because that was the nearest coast that would give them access to the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East in general. So these were migrants coming from Ethiopia coming from Eritrea coming from Somalia, Somaliland and further afield. Looking to basically rent out their muscles as laborers on farms on the Arabian Peninsula places like Saudi places like United Arab Emirates, labor jobs in urban centers. And some of these people were being pushed as I began to interview them by what became clear to me as an increasingly fickle rain pattern. Many of them were farmers many of them were from the Amharic Highlands of Ethiopia. And people were telling me, we would rather die crossing this desert than sitting back on our drawing farms and starving to death in-situ . That was an interview that I just heard over and over, mainly from the young men that were on the move there were young women as well.

Greg Dalton: You went to Georgia which you describe as an oasis of stability in a turbulent region. And then through Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan where you saw experienced epic rains. Tell us about that part of your journey.

Paul Salopek: Yeah, I think once I reached the old Silk Road, Central Asia has been traversed by human migrants for millennia. And in Kazakhstan the winter and spring that I walked across a region of Kazakhstan very isolated called Mangystau and it’s this very high plateau this kind of vast steppe country in the west of that country. The rains were so intense that I had interviewed people who were 90 years old who had never seen the kinds of plants that were springing up after these rains. Two things were happening here. One is the rains were so intense that they were turning to step into a bog which made them impassable. So the nomads were having trouble getting their sheep out even in the pasture because they’re getting bogged down in mud. And that created a problem for me as well I was walking with two Kazakh gentlemen and I had a cargo horse and we had to do all kinds of zigzags to kind of make our way slowly eastward towards Uzbekistan, one thing. The second thing is again the botanical explosion after these rains was extraordinary. I have photographs of it where steppe as far as the eye can see 360° on the horizon with no interruptions. It's flat as a pancake there's grassland as high as a horse's belly. In some cases even higher. And, you know, for the pastoralists this was like heaven, you know they're saying we've never seen a year like this since our grandfather's time. And again the kind of haunting thing was that they were plants that I would point to and see what was that, and they said, you know, we’ve never seen it before. So it could have been these seeds that were requiring massive amounts historic quantities of rain to finally germinate I just don't know. But that’s hinting at the other extreme, where like at least temporarily, at least you know, taken at face value. Here’s climate change that might have like some immediate positive impact on the local economy.

Greg Dalton: You’ve travelled through so many different cultures and so many different places. Do you talk to people about climate do they have words for climate change? You know, you’re talking with traders and nomads, farmers. Tell us about the concept they have of this, they’re so close to nature and yet it's changing in ways they haven't seen.

Paul Salopek: So when you’re traveling across continents like this on foot you cannot walk very far without encountering people. And when you encounter people on foot as opposed to being in a motor vehicle you can't just blow them off. You can't just walk by them and not say anything. You engage them, you know, you say hello, you’re polite you might have a very brief conversation or a very lengthy conversations in case maybe. It’s the opposite of lonely it’s the opposite of solitary kind of, you know, walking the earth alone. It’s been one of most social parts of my life. I have a dozen conversations at least a day sometimes dozens, you know, in India where there’s a village every 1.5 km. You talk to an awful lot of people. And I don't have to raise the issue of climate change. I don't, even from the very beginning of this project almost seven years ago it came up spontaneously. If you're talking to people who are living in rural economies who depend on the land who depend on farming or pastoralism, they bring it up. And I say, how is it going? They say, it’s okay, it’s alright, or, you know, generally it’s not alright. When you talk to any farmer whether it’s in Iowa or Ethiopia they always complain, that’s the way farmers are. I have farmers in my family. But now, it’s like, you know what, things are really strange isn't it kind of weird how, you know, early the rains came, or how they're not coming or how much runoff there is this year from the mountains or how little there is. And so it comes up if there’s a suite of like topics conversations as you're walking across the earth and you engage total strangers they fall into certain categories across culture, language, religion. It's I'm not loved enough or I’m loving the wrong person or somebody doesn't love me back, that's one kind of theme. And other is, you know, I hate the boss, and the boss can be the comments it could be, that’s the guy who’s like paying your salary or not. And the third is isn't the weather mighty odd, I mean that comes up again and again. And so these I’ve had variations on these conversations I think thousands of times. And it could be just a few words or it could be really long enough. If I’m doing a formal kind of interview for a story I can get quite detailed. It's everywhere. There is absolutely no disputing it.

Greg Dalton: And underneath that is there a fear, mystery, curiosity. What are the emotions underneath these people are living a lot closer to nature than most people who listen to this radio show and podcast, and I'm sure it's a range. But what's the feeling underneath when you encounter people is like, because some farmers I've talked to is like my daddy got through the dustbowl and we will too. We’re hardy people we’re used to being whiplashed by mother nature but is this different?

Paul Salopek: The underlying tenor of all of these conversations is anxiety. The ones that I've had to some tend some color of anxiety even if you're benefiting and I’ll give you an example. I walked through the Wakhan quarter a very remote salient of Afghanistan that kind of just like a finger from the Northeast up to touch on China. And it’s kind of all it’s a big mountain valley that’s hemmed by the Pamir and hemmed by the Hindu Kush in the Karakoram range very beautiful, very remote, very few roads. And as I walk through that region I was commenting and complementing the farmers on their orchards they’re beautiful new apricot trees were blooming and there were simply a lot of kind of cultural activity. New crops are going in, vegetable crops for the first time. And they’re saying, yeah, they said, you know, we’ve had more water than we've ever had before. And also the trees are flowering higher up earlier because it's warmer in the spring. And we’re kind in this golden era of agriculture in a place that have been kind of a cold desert pretty marginal. So again from warfare in the Horn of Africa to a place that was kind of like turned into an oasis a garden of Eden by climate change, but even there if you spent enough time with the farmers and just listen to them talk all night there was an underlying anxiety knowing that they were living on borrowed time. Because the water surplus was coming from glaciers that were melting unnaturally fast and that even worse times were ahead. Because once those glaciers were gone, the place is gonna be even drier than ever. So their kind of philosophy was, you know, we’re gonna take it while we get it, it was no guarantees what comes next.

Greg Dalton: Of all the places you’ve walked through what concerns you the most for climate migration. You think, wow, when this water comes or too much or too little or something that is happening now continues in motion. When these people go on the move, boy, this is really going to be quite a human migration.

Paul Salopek: India, without question, without question. The scale of the problem is so big that it invites denial from the farmer all the way up to the government minister. It is so huge. A recent study commissioned by the government of India itself revealed that up to 600 million people in India live in water crisis. Some of it is water quality but a lot of it just access to water. 600 million, that's twice the population of the United States and it's not looking any better right it’s going the opposite direction. So that is to me the biggest sort of climate change linked resource crisis in the world that we’re facing it’s a time bomb.

---

Greg Dalton: Journalist Paul Salopek describing some of the forces that are fueling human migration. You’re listening to Climate One. Coming up, we’ll hear how the impacts of climate change, security and mobility sometimes go hand in hand.

Dina Ionesco: The people who are the most vulnerable and most exposed, these are the people who are more likely to be trapped populations, who do not have the means to go somewhere else. And who do not have the means even to afford that one member of the family goes away.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about how climate fuels human migration. Movement of desperate people across borders is typically seen as a national security issue. But national security can also be at risk, when populations in areas suffering from climate instability, are unable to seek a better life elsewhere.

Francesco Femia: There's a tendency to separate out our strategic interest with humanitarian interest and actually I think they can go hand-in-hand.

Greg Dalton: Francesco Femia is co-founder of the Center for Climate and Security in Washington DC. He joins us along with Dina Ionesco [ee-uh-NESS-koh], Head of the Migration and Climate Change Division, at the U.N. Migration Agency in Geneva, to talk about the relationship between migration and security -- both national security and the security of migrants themselves. We begin with Dina explaining how experts might determine the current global number of climate refugees.

Dina Ionesco: Let's start in a very transparent way. I will tell you how many climate refugees are in the world. We do not know. This is the answer. That we do not know not because we are failing in trying to understand the issue, but we do not know because behind this notion of climate refugees. In fact, we are hiding many different realities of human mobility on of migration. So I can tell you what we know we know for sure that climate change impacts human mobility today in the world. And a lot of this migration would be internally to countries and not crossing borders. And we know that if we continue with these scenarios of climate warming and global warming, we’ll have millions of people who will be at risk and in risk zones from desertification sea level rise, extreme heat. But that doesn't mean that these people will become climate migrants or climate refugees because migration doesn’t work this way. In fact, you have even to have means to move and many of these people we are talking about are in great poverty and will not necessarily have the means to move. And once again, I think climate refugees it’s a notion that doesn't have a legal meaning today. It's something that talks to our spirits to our hearts. We realized that climate change impacts negatively people movements in the world. But you can’t have a status of a climate refugee today in our world. So this is why also we cannot say exactly how much of current migration is due to climate change. It's very multicausal.

Greg Dalton: Dina, where are the areas with the largest vulnerable populations. We hear a lot people coming out of the Sahel Northern Africa into the Mediterranean, and you’ve done an atlas of environmental migration. Where are the concentrations where are the people moving the most either internally or across borders?

Dina Ionesco: So we know that for instance in the past 10 years we have over 260 million people who are displaced because of sudden onset disasters because of storms because of floods. And the majority of this displacement remains in Asia but also we have storms for instance, that have hit very strongly Latin America or the Caribbean and there as well there are impacts. What it’s very difficult to know it’s the very slow onset degradation of the environment. So for instance desertification or sea level rise. And there we see that for instance areas that are very hot and where there is a lot of drought over the past years, for instance the Sahel, or sub-Saharan Africa more generally. There has been a lot of migration but it's combined to other issues of conflict and for instance of poverty. We know also that from a lot of evidence we have now on sea level rise that coastal zones and in particular low lying delta zones around the world everywhere where there are deltas also for instance Vietnam or Egypt or even in Europe delta areas of the Danube or of the Rhine. These are areas that will be strongly impacted. And then we have also the example of very small island states, in particular in the Pacific, but also in the Caribbean who are very much affected by both sudden onset storms and very slow degradation of the coastal zones of the ocean reefs of the acidification of the ocean and there as well there is migration from this zone. So we have displacement type of movements mainly related to sudden events. And then we have different types of migration very often internal and very much related to development or to conflict in relation to this very slow degradation of the environment.

Greg Dalton: Francesco Femia, 260 million climate refugees that’s a huge number, she said concentration in Asia. How does this affect U.S. national security?

Francesco Femia: Well, I think it’s important to note first of any migration out across borders or even within borders is not by itself a security issue. I think the main thing that we’re concerned about and I think this is how many in the security establishment might see it here in the United States, is what does that migration do to political stability in a number of areas around the world. And also, how do host countries react to that migration. How are political forces you might describe as ethno-nationalist political forces going to take advantage of these kinds of dynamics, whether they're real or perceived problems and does that disrupt the security environment. And from our perspective, it's a very dangerous dynamic but I think the policy recommendation would be to figure out more flexible ways of absorbing that kind of migration and also making significant investments in climate resilience in places where we are seeing displacement as a result of climate and other factors. Rather than, you know, basically the armed lifeboat response which is put up walls, implement draconian immigration standards. Because ultimately, even when walls “work” that leaves those countries where people are trapped unstable politically unstable and that can have security consequences as well. And so I think the response right now that we’re seeing in general, is the wrong one. But I have hope that cooler heads will prevail.

Greg Dalton: I interviewed Ray Mabus when he was secretary of the Navy for most of the, if not all the Obama administration and he talked about how the U.S. Marines are often the first in when places are, there’s a big disaster response whether it's the tsunami out of Indonesia, etc. How is looking at the prospect for more migration, how is that affecting U.S. military doctrine its presence around the world thinking that the Marines are often at least for the U.S. the first ones in?

Francesco Femia: Yeah, I think as Dina was mentioning before with quick onset disasters it is starting to enter into the thinking of the U.S. military quite a bit. I know U.S. Pacific command for example going back to when Admiral Locklear was the commander there called climate change the greatest long-term threat to the Asia-Pacific region for example. And I think what the military is concerned about is if we're seeing more of these disasters greater disasters that are driving people to either have to migrate or to have to be protected or supported through humanitarian assistance. If these are happening more often they’re happening simultaneously, potentially, as we’re getting cascading disasters as one, you know, a major disaster leads right into another before recovery is possible. That this might be a serious strain even on the U.S.'s ability to deliver humanitarian assistance while other disasters are also might be happening in other places, including in the United States where the U.S. military has been increasingly called upon to support state forces and national guardsmen in fighting fires and other natural disasters. And so I think that’s a big concern and I do think the U.S. military is planning for that new world. I think right now they think it's something that they can deal with but actually when you look at the trends for climate change and the likely displacement that’s going to happen in the future when you look at sea level rise trends coupled with storm trends. Then I think there’s a real concern that the U.S. military's ability to deliver humanitarian assistance and disaster relief or HADR will be strained, particularly when you have a number of other war fighting missions on their plates etc. But it's a scary new world and I think the U.S. military recognizes that.

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining us I’m joined by Francesco Femia, Cofounder of the Center for Climate and Security. And Dina Ionesco, Head of the Migration and Climate Change Division at the U.N. Migration Agency in Geneva. Dina Ionesco, we talked earlier about trapped populations when people who leaves is it the really rich because you can afford to leave or the really poor because you can’t afford to stay and the middle income people stay. How does the income scale relate to people's decisions and ability to stay or go?

Dina Ionesco: Yes of course that's a very important question we have when we look into migration trends and strategy at family level at community level. And when we add in the climate change and the environmental issue it makes this equation even more complicated because you realize how much migration it’s also about perceptions. And that there are moments that the decision it's like a turning point for a family and that the environment more and more it's this turning point. We see this for example, in countries like Mali where the rainfall patterns have change and it has impacted agriculture people lose jobs and that leads to migration then. We saw this a lot in Americas when you see changing water resources and access to water resources. And this is the turning point the tipping point where a family decides to move. So you have examples where families will decide to just send one person ahead and very often it will be an internal migration. So there will be a strategy of sending may be one brother or the mother or one person from the family household to the city as a first stage of migration. And then it can lead to future form of migration that will be for instance international once the person has achieved already an income in the city. So it’s a very nuanced and complex story to define how people will decide to at one point that migration is the response to their situation. And very often you need indeed resources to move. So it's true that the people who are the most vulnerable and most exposed in the poverty trap I think these are the people who are more likely to be trapped population who do not have the means to go somewhere else. And who do not have the means even to afford that one member of the family goes away.

Greg Dalton: No one identifies themselves as a climate refugee. They’re often fleeing something else and climate may be a factor, but people don't identify as climate refugees. In fact climate refugees don't have any status under the 1951 Refugee Convention. Do you think that that should be reopened to include climate migrants or would that potentially backfire and weaken that important convention?

Dina Ionesco: Yes, it’s completely true that currently you cannot become a climate refugee under international law and that the Geneva Convention does not provide for persecution by climate change, that does not exist. You have to show persecution for other reasons and very often it's persecution by your own country. That’s why you need a third country protection or international protection. From all the work we've been doing now the International Organization for Migration it’s quite an ironic story. We have done so much work to identify the evidence on attributing some of the migration issues to climate change impacts and adverse impacts. And we are now convinced that it's really the case that the environment degradation and climate change are drivers of migration but very often combined with other drivers. But now we are not necessarily saying that changing the refugee definition and the Geneva Convention is the good response to this. First of all because as we discussed before a lot of this migration is internal, so it’s under the responsibility of the country. People are not crossing borders they are not asking for third country protection, which is what defines in fact that refugee protection. And second of all, the problem is also that it’s very difficult to isolate climate change and environmental drivers from the other drivers. So we might have very good intentions to create new visas or new protection regimes just for people moving because of climate change, but will they be able to prove that and how and would not this becoming at the end may be backfiring for people who might not be able to prove that or who are in deep poverty situation and where the environment has a strong impact on their movement on their mobility. But it's not the main factor. So this is why we are much more encouraging migration policy and practices responses that are not necessarily about the status as a refugee. But more fluidity in migration options more regular pathways for migration and more areas for countries to be prepared to receive people for instance for temporary time for a temporary visa humanitarian visa. These can be responses to people moving because of the climate change and the environment. And I'm saying this in a very personal way as a former child refugee myself. I benefited from the refugee status. So as a child running away with my family for political reasons in Romania and I'm saying this because I think many people do not want to be defined as refugees, because there are still negative images about refugees having lost everything and having to start completely something new and not necessary positive image. And I think I'm fighting also this idea I think that whatever your status on migration people moving it's very empowering as well to start a new life somewhere and to build something new and bring with you your own culture and learn a new one. I think it's extremely feasible. So I think in the context of climate change and of the environment this might not be the best solution we can offer to people who have to move because of these drivers.

Greg Dalton: Francesco Femia, I’ve learned in this conversation that most climate migration is internal within countries. In the United States, there's a few villages small populations indigenous people in Alaska and Louisiana that have already begun to move because of sea level rise that’s pretty clear. When you look at migration within the United States, will it be slow and manageable if not orderly or is there potential for rapid and disruptive migration within the United States because it’s either too hot, not enough water, hurricanes, etc.?

Francesco Femia: Well, I actually think we’re already seeing both migration that's quick in response to quick onset disasters. We saw this with Hurricane Katrina which displaced a number of people that had to essentially migrate. We've seen this more recently with other storms and also slow onset. You don't often hear about it but I'm actually here in Eastern Maryland and at the end of the southern tip of Eastern Maryland, you have entire communities who are being affected by sea level rise who are slowly but quite surely moving. You have whole areas of Dorchester County for example, where you can’t really get public services if you live near the coastline and they're not keeping up roads, etc. So people are slowly moving out. So I think it’s gonna be a combination of both slow onset displacement from sea level rise storm surges that displace communities where it's impossible to rebuild. And I think that's actually why you're starting to see some bipartisan sort of collaboration on at least accepting that climate change is a serious issue and starting to try to figure out some solutions. We might not be seeing that from the White House but we’re seeing it in the U.S. Congress for example. And if you're a politician in Florida for example, and you’re a Republican it's pretty impossible at this point to deny that climate change is happening. And I think this is the case for a number of coastal states and also states on the west that are facing wildfires. And so I think you are already seeing migration here in the United States it’s often not called migration and I think there's a tendency to think well that’s not really happening here we can’t have internally displaced people in the United States can we? But it's happening and I think it's gonna happen more and more if something is not done about it.

---

Greg Dalton: Francesco Femia, co-founder of the Center for Climate and Security, along with Dina Ionesco, Head of the Migration and Climate Change Division at the U.N. Migration Agency, on how climate fuels mass migration. This is Climate One. Coming up, connecting climate change and U.S. immigration policy.

Oscar Chacon: Changing laws in the U.S. to accommodate the inevitable reality of more people on the move is also part of what should be a much more realistic understanding and practice of shared international responsibility.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Climate One records many of our conversations with a live audience, at our modern and green new home on the waterfront in San Francisco. When you are in town come check us out. Our programs are open to the public and listed on climateone.org.

We’re talking about the political impacts of climate-fueled migration. Oscar Chacon is cofounder and Executive Director of, Alianza Americas, a network of Latin American and Caribbean immigrant organizations, in the U.S. I asked him how he gets people to connect the abstract climate threat, with more immediate, more personal immigraton concerns.

Oscar Chacon: People in Central American countries, you know, if you actually ask them why did you feel forced to leave your country, they would not tell you oh because of climate change. They will tell you the conditions that they experience that led to a moment in their life or there was no other option but to leave their countries. And those conditions when you begin to ask more details that’s when you actually discover the connection between changing weather patterns in their own countries, you know, changing dramatically the way people used to grow their food in the countryside as rural communities. And for more people in the U.S. to understand that it makes it easier to actually give some practical meaning on how we can actually work on building intersections that are meaningful and as far as getting people protected. But also in as far as changing our own system of laws in the U.S.

Greg Dalton: Lot of immigrants here of course send remittances back to the home country that's partly why they came here and some go back. Does the climate disruption the disruption of agriculture, coffee, etc. does that affect how much money they are sending back or where they're sending money to because, you know, there is that important flow of money back home.

Oscar Chacon: Absolutely. Remittances play such an important role in countries like Mexico any of the Central American countries are also the same story. And what is interesting about remittances as they relate to crises in their home countries is that they follow our counterintuitive behavior from our financial flows point of view. For example, direct investment private direct investment tends to keep away from countries that are undergoing crises. Remittances behave exactly in the opposite way. When crises hit, you know, when there is a huge storm or a serious situation of drought in Mexico or Central-American countries. What you see is more money being sent because people want to be more helpful to their relatives. So in that respect as I said remittances financial flows are very different than any other kind of financial flows that you can think of.

Greg Dalton: Scientists predict that there will be more disruption of agriculture that weather is getting more volatile storms are getting more extreme that’s gonna affect agricultural production. What does that say to you in terms of the future flow of people north can you envision whether that flow would be so much so massive that the U.S. might need, dare I say, you know, some kind of barrier wall to kind of tighten on the border because there were so many people coming north?

Oscar Chacon: Well, I mean I think that Central American countries Southern Mexico are bound to become more critical geographic places on the planet in as far as climate change episodes. And how these will actually affect in a very deeply the lives of people to the point that more and more people will indeed come to the conclusion that there is no livelihood for them in their countries, but to go seek opportunities abroad. And what that really means in practical terms is trying to come to the U.S. because that's the country they have had a historical relationship with. I yet don’t believe that we are too late. I think that there is still work to be done in countries of origin to actually prepare for the likely event that there will be even more severe change. Change is coming down the pipe in terms of climate change. And in this respect I mean I happen to believe that what we need to do is change our existing laws having to do with humanitarian protection to acknowledge once and for all that climate change is likely to become a chief reason why more people will be forced to flee the places they were born and the places they love. And frankly I think that that's a much better proposition than to actually build walls that in the end have proven historically to be very ineffective as far as stopping flows of people when those flows can perfectly be channel in a different way.

Greg Dalton: During President Clinton there was 12 million people deported out of the United States during the second President Bush about 10 million President Obama 5 million. I'm not sure how many has happened under President Trump. But that's quite a lot of people. President Trump gets criticized a lot for sending people out of the country but 12 million people, you know, that’s more than two times what happened under Obama. So your take on sort of deportation is it really as bad today as it’s made out to be?

Oscar Chacon: Well I think that we need to look at the metrics. I think that you may be citing numbers that are actually mixing up what are called returns from the U.S.-Mexico border versus actual deportations. Meaning people who are already settled in the U.S. they are captured and then sent back. There has been changes over the years in the way we count how many people were send back so to speak to their countries. Because I believe that the number you cited for the Clinton Administration it’s a combined number of people deported from within the country plus people that were actually send back from the border back into Mexico. And in this respect I mean I definitely believe that the question of deportation as a whole is actually a mistaken policy from the perspective that it has meant to spending very large sums of money, your money my money taxpayers money in an operation that in the end does not address the fundamental question of why have people left their countries. And I think we need to work much more creatively in addressing those inequities in Mexico and Central American countries, including those related to climate change or climate justice. And then we will be able to find a much more healthy humane way of bringing equilibrium to the question of human mobility.

Greg Dalton: Many immigrants of course are undocumented and unable to vote. Many are and have obtained legal status to vote. We’re in an election year there is often concerns that you know, immigrants or Latinos don't vote at high percentages. Is that gonna be different in 2020 given the stakes of the issues that you're talking about?

Oscar Chacon: It’s still too early to say but you are correct that people who happen to be Hispanic or Latino, you know, in origin in the U.S. and there will be nearly 32 million people who are born in the U.S. or naturalized U.S. citizens of 18 years or older in age who will be potentially able to vote in the elections in 2020. However, will they be able to come out in larger numbers than before? That is a question that in my view depends a lot on number one what are candidates proposing, you know, to what degree what they are proposing relate to the reality of people who are Hispanic Latinos in the U.S. And number two, who is the candidate? I mean if the candidate happens to be somebody they definitely they don’t feel a connection with, I think is going to be difficult to predict that there will be a surpassing of the precedents so far which is 49.9% participation rate by Latino voters, which was reached in 2008.

Greg Dalton: Would Julian Castro as vice president change that?

Oscar Chacon: It may but it will really depend both as I said, I mean, I gave you two answers in my previous answer. One is what are they really offering that is relevant to Latino voters and two of course, who heads the ticket. I don't believe that just having a Latino by itself is a magic bullet to get more Latinos engage. I think it will depend on how much money gets to be invested in Latino led organizations really doing the hard, heavy lifting to get people to come out.

Greg Dalton: Oscar Chacon, co-founder and Executive Director of Alianza Americas. You’re listening to Climate One. Lauren Markham is a writer reporting on youth, migration and the environment. She came to appreciate how climate amplified the immediate causes of migration after spending time in southern Guatemala.

Lauren Markham: What I was looking at a couple of years ago specifically is the intersection between violence, climate change, poverty, and migration. So I was in what's called the dry corridor of Central America, a couple of hours south of Guatemala City. In an area that has been for, you know, years and years and years very drought prone, but climate change has hit this region particularly hard and it's weathering the impacts of climate change sort of shouldering the impacts of climate change more, much more than many of the surrounding communities. And the region is a huge coffee grower so the main source of income there I think over 90% of families relied in some form on coffee. But the thing is that when drought comes in that weakens the plants and make those plants more prone to plague. So there was a huge incidence of coffee rust which decimated and destroyed a lot of the plants, meaning that a lot of the people there didn't have anything to live off of anymore and that forced people out of their homes and many to the United States.

Greg Dalton: And that La Roya is affecting coffee all over the world.

Lauren Markham: All over the world. Yeah.

Greg Dalton: And so La Roya comes in, amplified partly by climate. What choices do some of these people face and there are any particular individuals or stories you can tell us their story.

Lauren Markham: Yeah, absolutely. So I mean, essentially, when any place where there’s a cash crop that’s it’s a non-diversified economy, right. So anyplace there's a cash crop when that cash crop is decimated that means that there's no fallback plan, right. There's nothing that we can kind of do tomorrow in order to feed our families and to buy our food. So what happened was a number of those people were forced into the city where there are higher instances of gang violence. And in Guatemala City, people were also struggling to find jobs because it's a challenging economy in the first place. So people were either forced to the city or forced to the United States to attempt to start a life over. The thing is going to the United States requires taking out essentially a massive debt in order to pay someone to help you get there. So there is actually a really excellent report by Jonathan Blitzer, of The New Yorker, who wrote about this sort of cycle of climate change migration and debt, in which people are trying to go to the United States, once they make it there they end up in thousands and thousands of dollars in debt and having to work triple time to send this home, such that families don't lose their homes or their land. And in many cases there are families who are losing their land and losing what little they have.

Greg Dalton: And then you mentioned the intersection of poverty, climate and violence. And we know, there’s pretty strong research that rising temperatures actually increases violence, when humans get hot they get angry there's more fights there’s different there’s more conflict at the individual scale and country, you know, group scale and even nation state scale. More fights at ballpark, it’s really strong data. So talk about the intersection between sort of violence and we always hear about fleeing from gangs in those area.

Lauren Markham: Right. So, the northern triangle of Central America which is a region that includes Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador and has been for decades struggling with entrenched community gangs and entrenched community violence. And in this case, I would say that it's not so much the rising temperatures that are directly impacting the violence, but rather the violence in Central America is an outgrowth of the Civil War years and the immense trauma sort of decimation to families to people psyches to the economy. But gang violence in the northern triangle of Central America is also inextricably linked to poverty. That people are joining gangs, either by force as in someone will come in with a gun to your head and say if you don't join I will kill you or I’ll rape your mother or I’ll kill someone in your family. Or often by force of circumstances because there's no other way for them to find belonging on a psychic level but even more sort of immediate and dire no way to eat or they don't have anywhere to live. So that relationship between poverty and gangs is huge and climate change in countries that are highly agrarian climate change is only leaving fewer options, right, for farmers and fewer opportunities for people to lead any kind of realistic subsistence life. So I wrote a book called The Far Away Brothers that follows the story of two identical twins from El Salvador who are fleeing gang violence. One gets on the wrong side of the wrong guy in town and has to leave pretty quickly and then quickly the family figures out and realizes that twin number two because he looks exactly like twin number one has to follow, you know, in his footsteps because he’s at risk of being killed. And they’re in a really rural part of El Salvador and their father owns some land and they’re subsistence farmers, nine kids in the family. He's an incredibly expert farmer and he's managed this land his whole lifetime he's getting older but he's managing this land. And when there's some extra tomatoes or some extra beans the mother will take it down from the rural area to town and try to sell the extras. But I have this small piece in my book that felt like sort of, an extra mention at the time of writing it, but it feels to me more and more over the past couple years like it's almost the most important piece of the book. It’s a piece where the father, I went to visit the family and the father sort of pointed to a basin of some of his recent crops. And he points to them and I said, oh those oranges they’re sort of back in the back so they were at a distance. And he said, “Oh no, no those are tomatoes I don't know what's happening but my tomatoes are all orange. And we have so many of them they're not horrible tasting, but they're not great. And we have so many of them and no one will buy them at the market. No one will buy these tomatoes and I just I can't possibly understand what's going wrong.” And he thinks that it must be him, right. He thinks that it must be something he's doing wrong even though he's planted his tomatoes the same way forever. And that was compelling to me because I think it speaks to the fact that in many of the places that are most adversely impacted by climate change, and where where climate change is increasingly a push factor when it comes to migration people don't have a lot of education about what climate change is and what it means and what's causing it. And there's sort of like a heartbreaking, you know, piece of that tale as though which is that this man sort of thinks it’s something that he must be doing wrong.

Greg Dalton: So you’ve also interviewed people in Gambia, Pakistan elsewhere. Are there differences in terms of either the language that people use or their relationship to nature, how they understand climate change in their way. Because it is such a global problems like oh yeah, that's an industrial problem. We have clean air here. That’s not a problem here. We’re a poor country that’s, I don’t know, do you have a counter to that?

Lauren Markham: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I guess my experience has been in interviewing people kind of in the throes of migration all over the world is that I've never met anyone who said I'm a climate refugee. And most of the time people when they give their reasons for why they're migrating poverty tends to come up or the lack of an ability to make a living somewhere. And I've also found that often when you keep pressing against that and you keep asking well tell me what was it like and what had changed and why all of a sudden, you know, why now, you know, why not five years ago. And people will say, oh well, you know, I talked to some young men in Gambia and he said, you know well, it's harder to farm now because there's more sand in our soil. And so this is not a young man who is saying I am a climate refugee or I'm a climate migrant he's saying because of climate change and I’m not using that word, right, but he’s essentially saying because of climate change I am having to leave. But I am defining that as poverty or as an inability to make a life in my home.

Greg Dalton: So then what’s the solution to this if climate change is going to drive more refugees out of places because of poverty amplified by climate economic development to try to keep them in their home country or what is the solution?

Lauren Markham: Yeah. I mean, I'm so happy you asked that because I think we often talk when it comes to migration about what we do once the migration has happened. And the important thing to do, right, is focus on the root causes. Most people do not want to leave their homes, right. Most people do not want to set off with very little on their backs to a foreign land to start over. So to me one of the most important interventions is having like global climate solutions as well as local climate solutions and interventions to make it possible for people to live. And I don't mean sort of, you know, barely live but actually like survive and thrive in their home countries.

---

Greg Dalton: Lauren Markham, author of The Far Away Brothers: Two Young Migrants and the Making of an American Life, on the challenges of climate-fueled migration.

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast climateone.org. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review wherever you get your pods.

Greg Dalton: Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Sara-Katherine Coxon is the strategy and content manager. The audio engineers are Mark Kirchner, Justin Norton, and Arnav Gupta. Devon Strolovitch edited the program. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, where our program originates. [pause] I’m Greg Dalton.