Indigenous Perspectives: What Makes a Just Transition?

Guests

Chéri Smith

Steven Wadsworth

Raylene Whitford

Maui Solomon

Summary

We often talk about a “just transition” from dirty to clean energy as if the term means the same thing to everyone. Indigenous people have seen their resources extracted and exploited to further the wealth of others for centuries.

Indigenous people are not a monolith — there are so many different tribes and experiences. Many of those experiences have been shaped by a long history with colonization: white outsiders, and later the U.S. government, systematically killed, abused, and betrayed Native people over the course of centuries. Tribes were forced from their historic homelands to reservations, which were often on very undesirable land.

The young U.S. government signed treaties with tribes, acknowledged them as sovereign nations, and then routinely ignored those agreements in service of its purposes. And in the years since, major corporations have extracted resources from Native land — leaving behind poisoned water and soil. Steven Wadsworth, Vice Chairman of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, says, “We've seen what kind of damage, you know, doing mining does. And you're asking a small amount of people to let us destroy everything that you've fought so hard for generations.”

Now another industry is looking to expand to indigenous land: renewable energy. While many welcome the opportunity for clean energy, others are wary of being exploited once again. Chéri Smith, President & CEO of the Founder at Alliance for Tribal Clean Energy, says, “For it to be just, it should include our Native people building it. It shouldn't be outsiders coming in and usurping all of the value of these systems and sending it off res, or out of the community.”

“Solar energy is important for the tribe and it has been for many years. So, before the big movement of installing solar farms, the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe was one of the highest numbers per capita of solar energy,” says Billie Jean, a Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribal Elder. Despite embracing solar, the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe currently gets most of its energy from a methane-burning power plant off the reservation, sold to them by the outside utility, NV Energy.

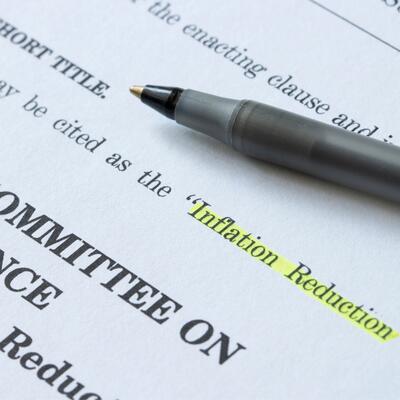

The Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, was supposed to make the transition to clean energy more economically feasible for everyone, including Indigenous communities. But because Tribes are considered sovereign nations, the funding mechanism is unworkable for many. Tribes would have to put up lots of capital for the projects and then file for a tax refund, but that poses a huge problem. As Steven Wadsworth says, “You can get 40 percent of that back when you file a tax return. However, Tribes, we're independent sovereign nations. We don't file tax returns. So how are you supposed to recoup that money with something like that in the IRA?”

Outside the United States, Tribes can face additional challenges when it comes to a “just transition.” “In my home province, we are not even allowed to say the term just transition,” says Raylene Whitford, Founder of Canative Energy. “That is a bad word because I come from a very petro-centric oil producing province in Canada. But in her opinion, “We need to be thinking forward. We can't continue to do what we're doing because it is destroying the environment”

“Modern society think indigenous people want to go back, turn the clock back a thousand years. It's not about that at all. It's about taking those lessons and those values and that wisdom that's accumulated over thousands of years and applying it in a modern day context,” says Maui Solomon, Executive Chairman of the Moriori Imi Settlement Trust.

This episode was produced in collaboration with the show On Shifting Ground with Ray Suarez, featuring Suarez as a guest host. Additionally, Sarah Howard provides field reporting.

Episode Highlights

3:20 Chéri Smith explains what a “just transition” means to her

6:35 Chéri Smith on extraction from indigenous land

14:11 Chéri Smith on the recognition of tribal sovereignty

20:24 Sarah Howard on solar projects and the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe

25:34 Steven Wadsworth on the tribe’s first experience with solar heating

28:05 Steven Wadsworth on the difficulty for tribes partnering with outsiders

37:35 Raylene Whitford on the recognition of indigenous rights

38:31 Maui Solomon on indigenous rights

44:04 Maui Solomon on a “just transition”

Resources from this Episode (4)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: I’m Ariana Brocious

Greg Dalton: And this is Climate One.

Greg Dalton: We often talk about a “just transition” from fossil fuels to a renewable energy as if the phrase means the same thing to everyone.

Ariana Brocious: Yet the reality is that different communities have different needs. This week we’re going to hear from indigenous people about what a just transition means to them .

Greg Dalton: Now we know that indigenous people are not a monolith – there are so many different tribes and experiences. We’ll hear from a couple of them today. But many of those experiences have been shaped by the historic backdrop here: from the earliest days of colonization, white outsiders and later the U.S. government have systematically killed, abused, and betrayed native people. Tribes were forced from their historic homelands to reservations, which were often on very undesirable land.

Ariana Brocious: The young U.S. government signed treaties with tribes, acknowledged them as sovereign nations, and then routinely ignored those agreements in service of its purposes. And in the years since, major corporations have extracted resources from native land - leaving behind poisoned water and soil. Just one example of this is the decades of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation, which has contaminated land and water.

Greg Dalton:That story of extraction by non-native people is the story of “Killers of the Flower Moon.” And the bulk of the benefits of that extraction rarely go to the local people.

Ariana Brocious: So it makes sense that tribes may be wary of partnering with outsiders to install renewable energy projects on their land.

Greg Dalton: But a lot of tribes don’t have the capital to develop large-scale wind or solar farms on their own, even when their sovereign lands get plenty of wind and sun. Rich is land and minerals but not rich with money.

Ariana Brocious: Right. There's also an issue of “energy poverty.” According to the US Department of Interior, here in the Southwest, 21% of homes on the Navajo Nation and 35% of Hopi Indian homes are unelectrified.

Greg: Wow I think of energy poverty in Africa, not in the United States.

Ariana: So while you and I might talk about transitioning the electric grid from coal-fired to wind or solar, people on the Navajo reservation, for example, talk about transitioning from no electricity to any kind of electricity.

Greg Dalton: Wow. Yeah. I can see that. So a “just transition” doesn’t mean the same thing to everyone. Another term I’ve been hearing a lot when talking to indigenous people is the idea of being in right relation or right relationship. I still don’t claim to have a complete understanding of what that means, but generally I think it means that if we as people are in relationship with each other and nature itself, then we also have to have a responsibility to each other and other living things. So an important part of a just transition is doing so in right relation.

Ariana Brocious: We’ll hear the terms “just transition" and “right relation" more in this episode, starting with Chéri [Sherry] Smith. Chéri is a descendant of the Mi’Kmaq [Meeg-em-ach] Nation and President and Chief Executive Officer of the Alliance for Tribal Clean Energy. Here is what a “just transition” means to her.

Chéri Smith: A just transition, broadly speaking, means... by the people for the people. It means that indigenous people have the opportunity to design what their energy system looks like going forward, they have an opportunity to get some help with it. Because of the oppression that they've suffered for so many centuries. You know, a little help, please, is, is welcome to build an infrastructure on which our communities can start the next economy. And, and for it to be just, it should include our Native people building it. It shouldn't be outsiders coming in and usurping all of the value of these systems and sending it off res, or out of the community. It should be the tribes themselves or partnerships that are in right relation. And it should be built by native people for native people and that applies to any community. It should be built by the community. The jobs should be in the community, the operations and maintenance should remain with people in the community. If not, it's not just and the money just goes out of the community and into the pockets of the settlers again.

I'm of Indigenous descent. I descend through both of my parents from the Mi'kmaq Nation of so-called Maine and the Canadian Maritimes. But I did not grow up on a reservation. And tribes on the East Coast and in California as well, we were assimilated really. a long, long time ago. So we don't have, um, the experience that our, uh, plain state tribes, our Midwest tribes, uh, Southwest tribes have. We live in typical cities and towns, for the most part. So when I first after being in the clean energy space for the better part of three decades, when I first encountered what I call energy poverty, I was, I was devastated, astounded, shocked, you know, all of those adjectives to see that in the 21st century in America, that there were Native people living in abject poverty. Without access to electricity sometimes, and that's one form of energy poverty. But the one that struck me the most was the high costs of energy for Native people simply because they're Native people. And the culprit is oftentimes small cooperative utilities served by big suppliers. And the rates that Native people are charged versus non-Native are sometimes double or more for the same electrons down the same line. And when I saw how that contributed to this dilemma of heat or eat on reservations, I knew in that moment that my whole career in, in energy and in education, living at that nexus, that I, I, I had to do something. So that's how I came to the work.

Greg Dalton: Chéri Smith spoke with Ray Suarez, host of On Shifting Ground.

Ray Suarez: Isn't there an intense paradox embedded in the heart of this? Native people have significant presence in places that supply energy, whether it's hydroelectric in the Great Lakes, natural gas in Utah, uh, uranium and oil in the Southwest. But those resources haven't made Native people rich, or as you just told us, even secure. What has to change?

Chéri Smith: Well, it's a good point, Ray. Many tribes, despite the promise of riches under their feet, have not succumbed to, um, that pressure, and these, these tribes have upheld their sacred covenants to protect and preserve the earth, and so in, in exchange for that, they suffer from poverty. Those that have allowed the extraction on their lands have benefited. But it's usually the outsiders, the settlers, the Western corporations that are having most of the benefit. And clean energy represents an opportunity to move away from those extractive economies and extraction period and towards clean and regenerative practices, which are very much in line with Native ethos. And, and that's what has to change. When we're talking about energy development, clean energy development, and all the opportunity that exists right now, because of the IRA and related legislation, we have to make sure that we don't repeat what happened in our last build out of the electric grid in our country, for example, where it was built squarely on the backs of Native Americans. We need to make sure that tribes are not only having a seat at the table, but they're building the table and inviting everyone else to it. That's, that's what has to happen.

Ray Suarez: Recently, I've been on Crow tribal land in Montana, on the land of several different bands in New Mexico, and one thing they have in common, a lot of sunshine and not a lot of solar collectors. Is that one road that's, so far, not being fully taken toward energy independence?

Chéri Smith: Well, you've got to look at the history. For example, the Crow have a fossil development history and they went that route because they did not want their people to suffer from poverty. And they have had challenges with fossil development in their communities. There's addiction and missing and murdered indigenous women and people and all the things that come with outside developers being on your land and, and the extractive industries have harmed the tribe in many ways, even while paying the bills. So some tribes are not opposed. We don't see a lot of opposition to solar or to other renewables in themselves. It's just they don't want to have to give up a reliable source of revenue. So we have to do everything all at once. And solar represents a tremendous opportunity. It is the low hanging fruit. We work with tribes on all kinds of renewables, but solar represents the cheapest form of new energy generation in our country, right now in the world. And with tribes controlling 2 percent of all land in our country, 5 percent of that is ripe for renewables development. And it makes Indian Country a very valuable place to do business and to develop solar. So our job is to protect the tribes best interest and to vet those developers with direct pay and elective pay and the wonderful tax incentives that are now available as well. We are standing shoulder to shoulder with tribes and our subject matter experts are helping to, uh, ensure that their best interests are protected throughout the process.

Ray Suarez: Earlier on, you mentioned that there's been broken promises and exploitation and failing to live up to their side of the covenant from energy production industries. Is there at long last enough accumulated expertise on how to shape these agreements, how to shape these covenants so that Tribal organizations don't get fleeced, don't get exploited, don't end up with falling way short of what they're promised on the front end.

Chéri Smith: That expertise, that wisdom has always existed, Ray. It's just a matter of whether or not the federal construct wants to acknowledge it and do what's right.

Ray Suarez: Tell me more about that.

Chéri Smith: This administration is, in my lifetime, uh, it's, it's the first time we're seeing a genuine dedication to righting the wrongs of the past. And when you think about the history from the deliberate extermination of the buffalo by colonists, westward expansion, manifest destiny, all of those things put not only Native people, all of us, um, every walk of life, every human that lives in this country is a victim of colonizationThat legacy is going to take, you know, my lifetime and my children's lifetime before I think we see a true reconciliation. But we're on the right track. I have hope.

Ray Suarez: If we're going to rebuild, uh, let's say a right relationship between governments and the tribes, between tribes in the land, between Americans in general and the land. What does that look like?

Chéri Smith: Well, first, it takes an acknowledgement of how we got here. And then a willingness to, in the words, there's a word in my ancestral language, the Mi'kmaq, when they were colonized very early, you know, the one of the hereditary chiefs I descend from on my mom's side was baptized Catholic in 1605. So you think about they were being colonized then and they I coined a term eduapdemonk, and I won't ask you to pronounce it, but eduapdemonk literally translated to English means two eyed seeing, and it means seeing the benefits of indigenous wisdom and knowledge and ways of being. And also appreciating and using responsibly the wisdom and technology of Western ways. We have to get to that point where both are considered equal by all. And we have to, uh, in our government, meet tribes where they're at. Don't make decisions and come later and tell us about them. Don't seek forgiveness instead of permission. And they don't even seek forgiveness throughout history, right? So what it looks like from here is having Native people in those conversations from the get go, not as an afterthought later, not as a checkbox on a federal application. Native people, marginalized communities all across the country, not just Native communities, need to be a part of the planning and the discussions from the very start.

Ray Suarez: Does recognition of tribal sovereignty, almost force a seat at the table where in other eras, uh, one might not have been assumed or given.

Chéri Smith: You would think, based on the term sovereignty, that it would, but it hasn't. And tribes being sovereign nations, but beholden to the federal government if they want federal recognition, which comes with, you know, certain benefits that tribes need to, many tribes that don't have economies of their own, need to survive and so that in itself is problematic and when you're talking about clean energy development there is still, uh, we are supporting tribes right now who have wonderful viable projects that could be life changing for their people. They could actually set them on a path towards energy sovereignty but the systemic inequities in the interconnection system and in just the grant application system in itself present hurdles. So it's, it's, it's one thing to pump billions of dollars into Indian country. It's another thing for tribes to have the capacity and the ability to, to actually get these projects done. There are too many hurdles. And that's what we're focused on now, is eliminating those hurdles. And philanthropy has been picking up the slack of government and, but it, it's going to take radical change within Washington for this to be a just transition.

Ray Suarez: Certainly in the western United States, a lot of tribal land sits on pretty big parcels, but is thinly populated. And the energy infrastructure is terrible in those places. Now, if you look at the example of the telephone, in places where telephone infrastructure was terrible, it just sort of leapfrogged the home, hardwired phone, and we just went past it, when finally, in a lot of places in the world, people could have telephones. They never had a wire that ran up to their house. Is there a way to leapfrog and not lay hundreds of miles of copper to each individual homestead? And are there possibilities offered by more recent developments in transmission and distribution, that mean that, okay, instead of trying to get a do over for the 19th or 20th century, we go right to the front of the line for something new and better.

Chéri Smith: Absolutely. As I was saying earlier, lack of access to energy can be considered a form of energy poverty. There are, as we sit here today 35,000 homes on the Navajo reservation that do not have access. to energy 800 on the tiny little Hopi reservation, for example. Those lines don't go there yet. Do we want to wait for that copper infrastructure to reach them? No, what we're, we're looking at is developing microgrids and completely self sustained islanded communities that can use clean energy instead of worrying about all that comes with even being connected to the grid in those communities in many parts of the plains in the southwest being connected to the grid doesn't mean you have reliable electricity. If you're in a lot of these tribal communities you get it. It's at the end of the line You know, and, and you're the first to lose power, and it doesn't come back on for days. Right? And so because of colonization, we are dependent on electricity. So when, when your power goes out, and you're not used to being without power, you don't have refrigeration, you don't have pumped potable water, you don't have air conditioning when it's 120 out. So, yes, that's problematic and that's why clean energy, especially solar, represents such an opportunity to, to, to solve those problems. But the costs of acquiring the money from the federal government to do those projects and the systematic barriers that still exist are the issue. And when you can offer community solar or residential solar to your people, the avoided costs there, you know, when you take that bill away from a family that is struggling, they're not buying, you know, Gucci bags with it, right? They're, they're buying clothing and better food and, and medicines and it's, it's a tremendous impact on a family that's in poverty to have the energy bill go away. And so it is smart for any tribal community and any community in general to take advantage of what clean energy means.

Ariana: Cheri Smith is the founder, the president and CEO of the Alliance for Tribal Clean Energy. She was talking with Ray Suarez, the host of our sister podcast: On Shifting Ground.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about a just transition for indigenous communities.

Our podcasts typically contain extra content beyond what’s heard on the radio… so if you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods.

Ariana Brocious: Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend.

Greg Dalton: Coming up, a tribe considers bringing more solar energy to their land, even though their first experience with solar hot water didn’t go very well…

Steven Wadsworth: Back in the seventies, we weren't there yet. And they were actually, um, all taken out. They just were not working. I was told we just had pipes burst left and right during the winter.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious.

Our next stop this hour is in Northwestern Nevada – on the Pyramid Lake Paiute Reservation. When you look at a map, you’ll see that at the center of the land is a 27-mile long lake, sort of in the shape of a teardrop. Most of the tribe’s income is currently generated by that lake – including fishing and recreational activities on the water. Now the tribe is trying to use the renewable resources on their land in new ways. Reporter Sarah Howard takes us there.

SARAH HOWARD: When driving north from Reno on highway 80, you can feel the landscape change as you turn off the highway and reach the edge of the Paiute Tribe sovereign territory. The mountain range opens up to a valley and you can see the lake off in the distance. I expected the vast desert landscape, but I didn’t anticipate the fierce wind that whips across the terrain, cutting through anything in its way. It's a character in and of itself.

SARAH HOWARD: This land is the ancestral home of the tribe which includes their namesake lake. Billie Jean is a tribal elder and director of the Pyramid Lake museum:

BILLIE JEAN: We know that our ancestors lived here thousands and thousands of years ago. And they were able to survive based on Native plants and utilizing a lot of local resources for making baskets and hunting and gathering. We're known as the Cuyuhi Takata, meaning the Cuyuhi Eaters, basically, fish eaters.

SARAH HOWARD: On my drive in to visit the tribal offices, a long sleek black mass slid over the horizon. A solar farm that comes right up to the edge of the reservation, stopping just at the border line. That farm - not owned by the tribe – shows the vast potential for more solar in the area.

BILLIE JEAN: The solar energy is important for the tribe and it has been for many years. So, before the big movement of installing solar farms, the Pyramid Lake Paiute tribe was one of the highest numbers per capita of solar energy. The highway 447 was named the solar highway because we had so many installations of solar arrays.

SARAH HOWARD: Billie Jean says the early adoption of solar is a point of pride for many in Pyramid Lake.

BILLIE JEAN: We have been solar powered for a number of years. In fact, my son designed some of the solar arrays here at the Pyramid Lake Museum. The advantages for the museum with solar power is that we have lower power bills as far as electricity goes.

SARAH HOWARD: The array designed by Billie Jean’s son sits right near the circular shaped museum meant to evoke a tribal meeting house. The array is shaped like an arrow and points from the building to the mountains.

BILLIE JEAN: With the museum, we're responsible for educating the public, including our tribal membership, our tribal youth, so that they can understand where they come from.

SARAH HOWARD: Across the street from the museum is the High School, which is also solar powered, something all the students know a bit about.

JAZMIN: My name's Jazmin. We're at Premier Lake Junior Senior High School. I think it's really cool. I like it that it's solar because it helps our environment and more because it helps us as a school. Think it's important because it really helps keep our environment safe. It's not polluting our lake and it's not polluting the air quality here.

SARAH HOWARD: The tribe would like to build more solar – a LOT more.

JAZMIN: My dream for this community and its future is that it really grows into something more than what people see it as now. Us as a people is a strong community who knows what we like, who we are, and I think more people need to know about us.

SARAH HOWARD: At the moment, those plans are on hold due to investment and infrastructure limitations….. But Billie Jean is optimistic:

BILLIE JEAN: As Indigenous people, we've been here a long time. We've survived all kinds of trauma and tragedy. And so, as very strong people, we want our youth to be the same way and be able to carry on traditions.

SARAH HOWARD: With ample wind and geothermal resources – in addition to solar – the tribe hopes to become a literal powerhouse in the region.

BILLIE JEAN: We entrust our tribal leadership to make the best decisions because when decisions are made, not only do we have to think about today, but we have to think definitely for our future generations, our unborn generations.

SARAH HOWARD: The challenge for that tribal leadership is how to turn all that renewable potential into actual income. That will take savvy negotiation to access outside investment. Then, like so many renewable energy projects on both Native and non-Native land, it will join the long line to get access to the electric grid. Currently, the wait time to connect new wind or solar projects is about five years. For Climate One, I’m Sarah Howard.

Ariana Brocious: Right now, most of the Tribe’s electricity is generated by burning methane at a power plant off the reservation, sold to them by the outside utility, NV Energy. Steven Wadsworth, Vice Chairman of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, is excited about the potential to get significantly more solar on their land, both to reduce electric bills for his people and to generate income. He says the tribe was an early adopter of solar technology.

Steven Wadsworth: One of the earliest projects we did was it was in the seventies. Um, when we were building some new homes out here, we actually put up solar panels on the roofs specifically for the hot water heaters. And, you know, I mean, I know the technology is vastly improved today, but back in the seventies, we weren't there yet. And they were actually, um, all taken out. They just were not working. I was told we just had pipes burst left and right during the winter and, you know, causing flooding. So that was one of our first.

Ariana Brocious: So maybe a bit of a negative taste first,

Steven Wadsworth: Yeah, and then in the last 12 years, we've, uh, we partnered with a company that came out of Burning Man called BlackRock Solar, and they're the partners that we used to put up the infrastructure that we have now, and we have solar panels, I mean, we, oh gosh. We've got them through our, uh, elementary school. They're right in front of the elementary school. We have, um, we have a few different spots around our junior, senior high school. We have them powering our clinic, our senior center, our tribal offices, our police station, our museum. Our museum's the big one cause it's actually in the shape of an arrowhead.

Ariana Brocious:So even with this amount of solar that's integrated into some of these buildings and, you know, very important structures for the tribe. You're still dependent on this outside utility for the bulk of the energy. What is your dream or hope, um, that the Pyramid Lake Paiute could get developed on your own property?

Steven Wadsworth: Currently, you know, we, we would like to see something that would benefit our people, you know, um, if it, if it offsets their power bill, that's a big one. You know, we're, we're a very poor tribe. So, um, we have, I believe we are at 40 percent unemployment rate on the reservation. So that's just one of the things that we'd like to try to do. I mean, we definitely have the land. So if we could incorporate something like that, where we could, you know, provide, give something back to the membership, I should say,

Ariana Brocious: And there are solar farms, um, owned by others that go right up to the edge of your border. That's demonstrating that it's a great place to develop solar and you have the land for it. So what's stopping you perhaps from partnering with some of those companies to do larger scale installations on your land?

Steven Wadsworth: You know, there's a couple of different roadblocks. One of them would be, you know, trying to partner with the tribe. Like I said, we're very poor, so we can't really do the infrastructure ourselves. And then, um, various governmental programs like the, the inflation reduction act, getting some of that going, some of the, uh, language in there is It's a good idea, but it's a horrible execution because one of them is, you know, you, you do it and then you file a tax return and then you get refunded, you know, up to 40 percent back. But the problem with the language in there is that you have to do big projects. I mean, and then you have to put up the money upfront. We're talking, you know, I think, what was it? 60 million. And then you can get 40 percent of that back when you file a tax return. However, tribes, we're, we're independent sovereign nations. We don't file tax returns. So how are you supposed to recoup that money with, with something like that in the IRA?

Ariana Brocious: So there’s not a framework even to give tribes a way to access the money in the way that other companies or, or, you know, uh, groups can.

Steven Wadsworth: Yeah. There, there really wasn't the framework for that. Um, I, I know they were working on trying to redesign that language in there so that tribes can access it, but until they do, it's kind of just like, great. The money's just sitting there and what tribes can access it.

Ariana Brocious: So you've mentioned, money is an issue getting the capital to begin one of these projects. Um, land is not an issue, uh, but the sort of rebate or, um, incentives that are built into the Inflation Reduction Act don't work as they're currently written. So if there are these hurdles, how are you hoping to move forward with developing more solar? Are you looking for investors to come in and provide that upfront capital, but still allow the tribes to have ownership? Are there hybrid arrangements you can work out? Um, you know, what's possible?

Steven Wadsworth: I think we're taking into consideration everything. Um, one of the things that we've actually thought about too is ownership of the panels. Currently it's one of those, one of those weird. I guess weird takes on, do we want to own the panels or, or would we just rather, you know, rent the land, which I think is kind of more, more where we're moving to, um, because, you know, with ownership, with something breaking, you know, something not working, we have to go out there and fix it. And then the other part also becomes a reclamation. With all that land, you know, in 25, 30 years when the panels are no good anymore, do we want to be on the line to try to get them out of there, to recycle them? To bring in another project, you know, maybe the technology vastly improves, but it's still that cleanup and reclamation is always on our mind, just because we've seen, you know, what's like, we have a mine on the reservation, we've seen what kind of damage that can do. Um, and especially when they leave, who's cleaning it up, who's responsible?

Ariana Brocious: This episode broadly is looking at the idea of a just transition, which is a term that's gotten a lot of, um, more usage lately. It's been talked a lot about in terms of energy and renewable energy. But maybe it doesn't mean the same thing to everyone. And so I'm curious what do you think when you hear just transition or what it means to you?

Steven Wadsworth: Well, to me, it means, you know, I guess being fair. Oh gosh, I mean, you know, it's, it's real hard to think about, you know, just, just from the history of how America treats Native Americans, you know, when it comes to what land, you know, a lot of us were forced on their land. We, we at Pyramid Lake are very fortunate because this is our ancestral homeland. Oh gosh, it's just, it's very difficult because, Native Americans have just been treated so unfairly since the beginning. But now we're just right at the time it's gosh, you know, I, I, I think about Thacker Pass, which is not, you know, a hundred miles from here with the lithium mine and it's. It's just, again, I'll say it again, it's not fair, how can you expect, you know, a small amount of people to, I guess, save the world? That's what it feels like, because we've seen what kind of damage, you know, doing mining does. And you're asking a small amount of people to let us destroy everything that you've fought so hard for generations.

Ariana Brocious: So let's stop there for a second. And for people who don't know, because I think this is a great example, but I want the listeners to know what we're talking about. Thacker Pass, as you mentioned, is a lithium mine. Can you say a bit more about it and why it's, it's been controversial,

Steven Wadsworth: So yeah, Thacker Pass has the potential to be the largest lithium mine in the world. And you know, with mining, any mining, you know, you, you just destroy everything around there. There was, um, there were, that was the site of a Native American massacre back in the 1800s, which is why they try to protect it. Um, it's not, it's not my tribe. It's another tribe out that way near, um, Winnemucca. Um, but again, you're, you're asking a native tribe where that's their ancestral homelands, you know, to let's just destroy it. We know it's sacred to you, but we're gonna, we're gonna do what we can because, you know, the world's heating up. It's, uh, it's tough.

Ariana Brocious: When you think about the future of the Pyramid Lake Paiute, what's your hope for what that looks like when it comes to energy production?

Steven Wadsworth: I'm hoping we can get some projects going out here. I know it's just my hope, you know, it's for the people. You know, that's, that's who elects me. That's why I sit up here. You know, I spent, I spent three years as the senior services director here on the reservation. And it's mostly women and talking with those old ladies. I call them my old ladies. You know, it was. It was just so funny just to hear them talk, you know, because a lot of these ladies were born in the thirties, and they've seen, they've seen this place when it was nothing. They've seen it go from little shacks. We had little shacks, um, wigwams and you know, four, four walls, a roof and a dirt floor. That's what they've seen growing up in the thirties. And then they've seen, of course, you know, where we're at today and progress has kind of stalled. So I'd like to see progress continue. And I think the next, next bit would be that electricity, the solar, uh, and you know, making the, making a, making this a place where our people can come back to, getting something out here, a big project like solar, where we can make some money, offset power bills for our people. And that way we can, you know, save that money and let's say, build more homes because, you know, we have, we have, oh gosh, I think our housing list here is 60 families looking for a home. And so if we could just do more to build more homes, when we do those projects, that'd be great.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. Stephen Wadsworth is vice chairman of the Pyramid Lake Paiute tribe. Stephen, thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Steven Wadsworth: Oh, thank you very much.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about how Indigenous communities are tackling the clean energy transition. This is Climate One. Coming up, Revenues flowing from fossil fuel projects make it difficult for some indigenous communities to move away from them.

Raylene: A plethora of communities are dependent on oil production, gas production, transport, etc. The way our industry has developed has tied us to the economic, prosperity that these projects can bring.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. The challenges indigenous people face in transitioning to clean energy are by no means restricted to communities in the United States.

I want to turn now to a conversation with two indigenous leaders: Maui [Mau-ee] Solomon is Executive Chairman of the Moriori [morr-ee-OR-ee] Imi [ih-me] Settlement Trust in New Zealand. And Raylene Whitford is founder of Canative Energy, a Canadian social enterprise dedicated to economically empowering Indigenous communities who have been impacted by extractive industries.

Raylene and Maui spoke with Ray Suarez for our sister program, On Shifting Ground.

Ray Suarez: Raylene Whitford, there have been many times, and certainly in the western United States as well, when indigenous people who were often, um, taken off their ancestral lands, parked somewhere else, and when they found out the somewhere else where they were parked was now very valuable, they tried to move them again, and they just said, No, are we at a point where we can't go back to? Those old ways of, uh, of handling indigenous people. Are their rights recognized in a way that makes that backsliding impossible?

Raylene: What I'll offer as a response is that, One, I want to recognize that all Indigenous people, we're not a monolith. We have a massively diverse, um, set of cultures, governance systems, spirituality, languages. So you know, it's, it's one thing to advocate for the recognition of Indigenous rights and inclusion, um, but we are not the same. And, you know, in Canada, Latin America, Asia Pacific, you know, the, the one thing, well, one of the things that we have in common is the oppression and the colonization and the process of being removed and kept away from any of the, the decisions that are made about us. So it's been a very patriarchal approach in Canada. And I would say that, you know, we're only at the beginning of recognizing and upholding Indigenous rights in, in, in my country.

Maui: I'd just like to have the chance to also respond to that question. Um, because it's not about going back to the past. And this is the issue a lot of, um, the developed nations and, um, Modern society think indigenous people want to go back, turn the clock back a thousand years. It's not about that at all. It's about taking those lessons and those values and that wisdom that's accumulated over thousands of years and applying it at a modern day context. You know, we talk about traditional knowledge. Traditional knowledge continues to evolve. We have modern day traditional knowledge based on our ancestral values. How to care for the earth, how to care for the sea, how to care for the sky. These are the things that I think need to be factored into how we're managing our planet. And, uh, if you look at it, we've managed it just in the last two hundred years is the reason why we're now facing this crisis, this climate crisis, and yet, indigenous peoples, we've, we've traded Maitre Nor forever, for, for thousands of years. Um, but, when indigenous people come to the, to the, table to do, um, you know, to talk economics and trade and commerce, you know, it's not about, it's about putting people and the planet, uh, above profit because if profit is the sole motivator, which it has been for the last hundred or so years in our capitalist and materialist and consumer society, then we're failing, and we're failing as a planet. We're failing as a species. And I think this is where indigenous people have a really important contribution to make.

Ray Suarez: One of the themes this year's is making a just transition to a new energy economy. I understand that you both have problems even with the phrase, so why don't we pick that apart and talk about, uh, justice and transition. Raylene,

Raylene: So in my home province, we are not even allowed to say the term just transition. That is a bad word because I come from a very petro-centric oil producing province in Canada. Um, I think the term just. That means different things to different people. Um, I think that to me, it means being as inclusive, uh, as possible or as, I don't even know how to put it into words. It's being inclusive as you can of the unheard. Um, I don't like the term underserved because I think that's imbued with a power differential. And, you know, that is not going to help us get through the challenge that we have in front of us today, but I think it is involving the unheard and these different perspectives, these different knowledge holders, these different rights holders to participate in the, the change that we all have to make. If we don't, we will continue to have projects delayed, permits, uh, revoked, and just in this terrible conflict that, you know, we've faced, um, well, in Canada and in the U. S., for example, to date, so we have to be inclusive, we have to listen, and we have to be open to a diversity of perspectives.

Ray Suarez: Well, right at the beginning of your answer, you noted that, uh, you come from a part of Canada that's involved in energy extraction. In fact, in Alberta, the tar sands, uh, are both a treasure trove of, uh, of British thermal units, BTUs, and also some of the dirtiest energy possible to use on the planet. So when we think about the Alberta tar sands, and we think about just transition, what would you tell Justin Trudeau? What would you tell your fellow Albertans? What's the answer?

Raylene: There's no simple solution. So, for example, in my province, we have a plethora of communities who are dependent on oil production, gas production, transport, etc. So, you know, the way our industry has developed has tied us to the economic, um, prosperity that these projects can bring. I do think, though, that we need to be thinking forward. We can't continue to do what we're doing because it is destroying the environment, and the world is moving on. So, what I would encourage, uh, my relatives, our communities, our Indigenous people, and the Canadian public is to find a, a meaningful path forward that involves the input of everybody and prioritizes Indigenous rights holders. Um, there are several communities in, in my home province and across Canada who strongly support oil production. Now, should we make that decision for them and say that that should not happen? Well, that doesn't allow them to be self determining nations, which the United Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples provides us. So, I think being open to having that conversation and bringing a diversity of perspectives is key. I also think that it'll be a reiterative process, so we can't come up with one report that has a very clear, linear pathway to net zero, but I think working better together with stronger relationships will give us a better possibility of arriving at that.

Ray Suarez: Maoi Maui Solomon, when you hear that phrase, just transition, what does it mean to you? And do you have any hesitancy about using it?

Maui: As a lawyer, um, in a previous life, I thought about the word just, and, and it's, um, It's a relative term, really, isn't it? What's just to you might not be just to me or to Raylene. And so, who's determining what's just? Because if you're a multinational, sort of, um, oil producing company, um, you, you might say it's just, just to continue, you know, producing fossil fuels to, to provide, uh, you know, to, to help the economy. But if you're a tribe, or if you're, say, people in the Pacific Island nations who are suffering from rising sea levels and acidification of the ocean because of the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere, you're going to say, Oh no, that's not just. So it's a relative term. And so with anything you need to actually understand what are we talking about? The way that it's being discussed is to ensure that disadvantaged and vulnerable communities in transitioning away from fossil fuels to a net zero carbon and to alternative uses of energy aren't unfairly prejudiced or left out. And if I look at my own small island community of Rekohu Chatham Islands, which is an island based 800 kilometers off the east coast of New Zealand, you know, we're addicted to diesel. Because, uh, diesel, you know, we've got a relatively small population, 600 people, but our mains power is supplied by diesel generators. Our fishing fleet is fuelled by diesel. Um, farm machinery is fuelled by diesel. The third aspect of our economy is from visitors, from tourists, and they get here from flying over from New Zealand and Australia. So, you know, if suddenly we were to go to a alternative, or, or to be weaned off diesel, that's, it's not going to happen overnight. It has to be transitioned or happen over time. There needs to be a clear plan. But, we need to look at what resources we do have. There's the sun, there's solar energy, there's wind. Uh, we've got a lot of wind on the Chatham Islands. In fact, my father once told me it blows so hard on the Chathams, it blows everything off the land except the mortgage. And it's quite true. So we can utilize, um, that the sea is a great... its got two tidal movements within 24 hours, so we could be looking at generating power from the sea. And so, it's looking at what are the alternative sources of energy, and transitioning over time towards a more sustainable net zero carbon, uh, societies. But that's going to take time and, um, you know, when you're an addict, it, it takes time to be weaned off those things, right?

Ray Suarez: Well, yeah, I mean, and as Raylene noted, uh, you're both not a monolith, and in her particular case, there are tribal groups advocating for the continued exploitation of fossil fuels. So, if you look across the world, many of the poorest communities are indigenous people. They need economic growth. They need economic growth in order to become full shareholders and have that burden of poverty relieved and, and be able to live the life expectancy of their fellow citizens in, in these countries. Can you be for economic growth and, and what, uh, what the oil companies might consider against it at the same time? How do you strike that balance, Maui?

Maui: Yeah, no, that, that's a, that's a very good point. But, um, again, if, if we're just going to continue on the path we're on, we don't have a future. You know, that's the bottom line. And, and we're already at, you know, a minute to midnight. Some would say we're actually, we're past midnight, but I, I tend to live in hope. So, um, you know, we've got other, um, We've got wonderful technology today, and we've got wonderful natural resources. The sun is the greatest source of natural energy, um, on the planet. Well, not on the planet, but in the sky. We've got the seas, we've got wind, we've got these magnificent resources available, and we really need to do more to utilize them in driving our economy, our vehicles, our, our fishing fleets Like my ancestors, Polynesian ancestors, um, settled. You know, 30 square million miles of ocean over 3,000 years in the Pacific Ocean. And they did that by sailing, by using the, the wind. So, you know, why can't we be looking at, um, wind and solar to, to drive these big tankers around the world instead of fossil fuels? Um, some might say, well, that's impossible. But I, I think humans have demonstrated, you know, by going to the moon in the 60s, anything's possible.

Ray Suarez: That's Maui Solomon. He's the chairman of the Moriori Imi Settlement Trust. He joined me on Shifting Ground along with Raylene Whitford, director of the Canadian Sustainability Standards Board. Great to have you both. Good to talk to you.

Raylene: Hi, hi, Ray.

Maui: Yeah. Thank you, Ray.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One... We’ve been talking about what a just transition means to indigenous communities. This episode was a collaboration with On Shifting Ground – you can hear more wherever you get your podcasts.

Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency.

Ariana Brocious: Talking about climate can be hard, and it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Ariana Brocious is co-host, editor and producer. Austin Colón is producer and editor. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Wency Shaida is our development manager, Ben Testani is our communications manager. Our theme music was composed by George Young. Gloria Duffy and Philip Yun are co-CEOs of The Commonwealth Club World Affairs, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.