How Activism Can Win Bigger and Faster with Kumi Naidoo

Guests

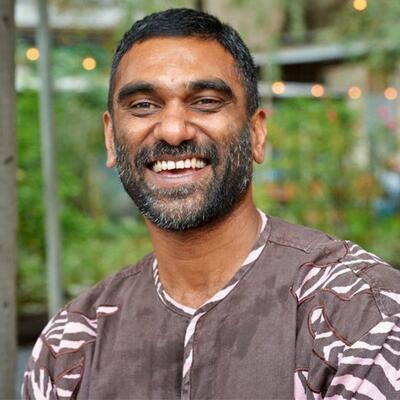

Kumi Naidoo

Alex Ajose Nixon

Mystic

Dana R. Fisher

Tamara Toles O'Laughlin

Summary

Kumi Naidoo is a world renowned activist and climate leader. Before going on to lead Greenpeace International then Amnesty International, Naidoo was a 15 year old anti-apartheid activist in South Africa. Naidoo says, “Many of us in that generation of activists, We lived on the basis that we could be killed anytime.”

Naidoo organized school boycotts against the apartheid educational system in South Africa, which made him a target for the Security Police. The situation became so dangerous that Naidoo had to flee South Africa and live in exile in the UK. Upon his return, Naidoo played a pivotal role in the legalization of the African National Congress in his home province of KwaZulu-Natal.

“The [South] African situation was pretty black and white, literally and figuratively. Climate and other struggles are actually a very different, more complex problem,” says Naidoo. The complexity can make it particularly difficult for climate activism to be effective. Climate advocates tend to appeal to the intellect, Naidoo says: “Facts, figures, policies, and proposals. Everything is aimed at the head, and we have ignored the heart.”

When we talk about change on a massive scale, the road to get there may require some compromises. Compromise can make solutions more durable and less affected by political winds. Naidoo is willing to forge alliances that include people from the oil and gas industry, especially the workers. “At the Paris Climate Negotiations in 2015, I shocked some journalists when I said the men and women who work in the fossil fuel industry are our brothers and sisters,” says Naidoo.

Kumi Naidoo points to another issue that is preventing more movement on climate solutions. He even describes it as a disease. Naidoo says, “It's a disease we can call affluenza. And affluenza is a pathological illness where humanity has come to believe that a good, meaningful, decent life comes from more, more, and ever more material acquisition.” Naidoo believes that people have become dependent on gadgets and status symbols. Naidoo says, “the struggle on climate change has to be a struggle to rethink consumption patterns.”

Even as the window to address climate is closing, Kumi Naidoo says “We still have a small window of opportunity. So long as that window is open, we need to keep our optimistic take on it.”

Of all the forms of protest and activism Naidoo has engaged in over the decades, he now places most faith in the power of arts and culture. This view is echoed by Hip Hop Artist and Educator Mystic.

“Art allows people to tune in,” she says. “I think sometimes when we're enjoying ourselves or engaging with art. some of our defenses come down.”

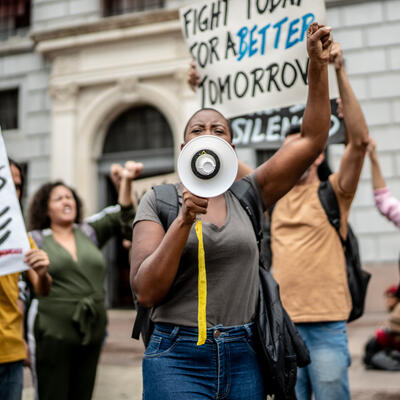

As the climate situation becomes more dire, some activists have chosen more confrontational tactics – like throwing soup on paintings or disrupting meetings. Sociology Professor Dana R. Fisher is author of the new book “Saving Ourselves: From Climate Shocks to Climate Action. She says the goal of the radical flank that engages in those more confrontational tactics is “to push the activism to a more extreme place that mobilizes people to be more willing to participate in moderate types of activism.”

Climate chaos will affect everyone, and that gives activists the unique opportunity to speak to a broad audience. Tamara Toles O’Laughlin, President and CEO of Environmental Grantmakers Association, says “We are in a time when the youth agenda is no different than the black agenda, than the indigenous agenda, because at the end of the day, we need to be in a space where we can move the needle for change because there is no separation of success here.”

Episode Highlights

2:15 - Kumi Naidoo on the passing of Alexei Navalny

9:24 - Kumi Naidoo on the power ordinary people have

12:44 - Kumi Naidoo on the tensions between inclusion and speed of climate action

17:01 - Kumi Naidoo on the “disease” of affluenza

29:12 - Kumi Naidoo on speaking to the heart and not the head

36:32 - Kumi Naidoo on the climate progress we’ve made

38:35 - Excerpt from Alex Ajose Nixon poem

40:18 - Mystic on the importance of art and activism

47:37 - Dana Fisher on confrontational activism

53:57 - Tamara Toles O’Laughlin on the shared climate agenda

What Can I Do?

Resources from this Episode (1)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. Growing up in South Africa, Kumi Naidoo became an activist at a young age. When he was just 15, he organized protests at his school against the apartheid regime.

Kumi Naidoo: Many of us in that generation of activists, we lived on the basis that we could be killed anytime.

Greg Dalton: He grew up to lead Greenpeace International and then Amnesty International. But he says that work was not always satisfying.

Kumi Naidoo: I cannot tell you how much time we have all spent in what young people now dismiss as handshake activism. You know, going in good faith and meeting with UN bodies, CEOs of big companies…it was a ritualistic exercise.

Greg Dalton: After decades of working for civil and climate justice, Kumi Naidoo has plenty to share about what works – and what doesn’t.

Kumi Naidoo: Facts, figures, policies, and proposals. Everything aimed at the head, and we have ignored the heart.

Greg Dalton: How Activism Can Win Bigger and Faster. Up next on Climate One.

Ariana Brocious: I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One.

[music change]

Greg Dalton: Each week on the show, we talk with people who have made climate action their life’s work. They’re scientists, writers, community leaders, artists…

Ariana Brocious: We talk with famous people like Jane Fonda, Al Gore, the writer Rebecca Solnit...

Greg Dalton: And also emerging young activists like Vanessa Nakate and Nalleli Cobo.

Ariana Brocious: Many of the voices you hear on this show answered the call to climate action – very early in their lives – and have carried that with them through their life and their work.

Greg Dalton: Whenever I talk to activists, I want to know: how do they think change happens and what’s the most effective way to achieve it? What’s the best lever to pull: do you protest in the street? Infiltrate corporate boards? Or do you need access to people in power, presidents and prime ministers to influence them?

Ariana Brocious: Our guest today has kind of done it all: he’s protested in the streets AND secured high-level meetings in the halls of power.

[music change]

Kumi Naidoo became an activist pretty early in life…

Greg Dalton: He grew up in South Africa. When he was just 15, he organized a series of boycotts at his school and others – they were protesting the segregated educational system under apartheid. That work made him a target for the “security police.” And he had to flee the country and live in exile in the UK for several years.

Ariana Brocious: But that was just the start of his career in activism and social justice. He was arrested for scaling an oil rig ... while he was leading Greenpeace International. He went on to lead Amnesty International. Now he’s a visiting scholar at Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law, where he’s focused on how activism can win bigger and faster.

Greg Dalton: He’s one of the few people I’ve met who seems equally at home at a protest and working the room at the World Economic Forum in Davos. To me his comfort with elites AND his ability to challenge those SAME elites makes him a really intriguing figure.

[music change]

Recently, I talked with Kumi Naidoo in front of a live audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. The event was just a couple days after the death of Alexei Navalny, the Russian opposition leader and anti-corruption activist – and his passing was really fresh in our minds.

Kumi Naidoo: It brought back lots of memories of people that I had lost in prison and in exile, killed through depression during the struggle against apartheid. And mostly it reminded me about what his message of his life was communicating, like we have seen with many people across the world over history. And what he was saying In his life was the struggle for justice is a marathon and not a sprint. And that sometimes ordinary people are called upon to make extraordinary choices. He had a choice after they tried to poison him not to go back to Russia. He chose to go back. And if you look at our Class of politicians today across the world in this country included, they don't come anywhere near Navalny in terms of having any sense of integrity and any sense of being able to put their lives on the line and do that which is right. And of course, I understand your former president made a comparison with his court cases with that of Navalny. And I just want to say we should highly disassociate ourself with any comparison between Donald Trump and Alexei Navalny.

Greg Dalton: You grew up in apartheid South Africa, talk about personal price, were you willing to give your life to the anti apartheid cause? Was there a time when you thought you might give your life to anti apartheid?

Kumi Naidoo: All the time basically. We got involved, at the age of 15. And I like to tell the story. Because at the front of the march, our slogan was “we want equality.” But then the slogan got to the younger kids at the back of the march. They were chanting, we want a color TV. We want a color TV. Truth be said though, we wanted equality and a color TV almost equally. And both appeared equally unattainable. But many of us in that generation of activists, We lived on the basis that we could be killed anytime. Because we used to go to funerals every other weekend, right? And at those funerals, people get killed, and it was a cycle, right? And when I was fleeing South Africa into exile, my best friend Lenny, says to me, What's the biggest sacrifice we can make for the cause of justice? And I say to him, Giving our life. And then, he says that's the wrong answer. He says, it's not giving your life. But giving the rest of your life. And at 22, he was like way ahead. He was the only person amongst us who got the intersection between racial justice and environmental justice. In fact, I jokingly say at that time he probably was one of only 5,000 voluntary vegetarians on the entire African continent. So we shrugged and cried and we went in different directions. Two years later I heard that Lenny had been brutally murdered by the Apartheid regime with three other young women from my home city. There were so many bullets in his body his parents were not able to recognize him at the mortuary. And I had to think deeply about that distinction between giving your life versus giving the rest of your life. We have to shift our young people from any logic about you should die for your country. We need to shift people that you should live for your country. You should live with purpose, both for your country and the world.

Greg Dalton: Apartheid human faces, FW DeKlerk and there were villains and there was this system and there was, the police, climate can feel so abstract, especially compared to civil and human rights. And so how does addressing climate require different tactics and thinking than the regime of F. W. DeKlerk.

Kumi Naidoo: Yeah as I like to say, the African situation was pretty black and white, literally and figuratively, right? Climate and other struggles are actually a very different, more complex problem. Let's say when I was doing human rights work and you're dealing with the issue of torture. With torture, you can take a person who has survived torture and they might have scars on their bodies, and you can take a photograph and you can communicate that. Or if somebody is homeless, you can capture the reality. The reality to show exactly what climate change is not that easy and say for us in Africa Even though we have contributed least to the problem. We are paying the first and most brutal price, right? And for us the manifestation of climate impacts is not like typhoons and hurricanes and tornadoes that you have here, things that is a massive media moment when it happens.

Greg Dalton: It's slow moving, it mores slowly.

Kumi Naidoo: Exactly, it's drought and desertification, which is one of the biggest impacts of climate change. Parts of our continent are becoming completely depopulated, but it's hard to make the connection to climate change is easily the other challenge we have with climate change is it's not in, yeah, in absolutely an immediate way every single day. It can be there. If you're following the news in different parts of the world, but if people live in a particular community, like we come from Durban, right? And two years ago on two days, we lost 500 people like that through a massive storm, like flooding, like we've never seen before hundreds of billions in, in, in rands of infrastructure.

Greg Dalton: Barely made the news here.

Kumi Naidoo: Of course. And right now, I don't even get surprised when lives are lost in the Global South, that the Global North just doesn't register it, because it's just become the norm. We fight against it, we want people in the Global North to understand that we our lives are no less, uh, cheaper than your lives are. I just would end this point by saying, when we say Global North and Global South, please understand what we are saying is that the overwhelming global majority in the global south and the minority in the global north. I understand, look at the numbers that we are talking about. So we have a deeply undemocratic world and that is probably one of the main reasons why we're not making progress on climate.

Greg Dalton: Let's talk about intersectionality as it relates to getting more people involved. You created a graphic that shows four quadrants,four paths for how people can get involved on climate justice. Tell us about the different pathways and people don't think they have power when it comes to climate because it's so big. I talk to a lot of powerful people who run the U. S. Navy, the state of California. They're like, I can't, I can't really put a dent in this. It’s hard.

Kumi Naidoo: This is the most important question for me, right? Because our starting point of activism, those of us who say we need to change things. We start with a mentality about how people are oppressed, repressed, excluded, marginalized, and so on. And what has happened over time unwittingly is we have actually come to think that people have much less agency than they actually, notwithstanding all those injustices that people have absorbed, that they have, right? And what is needed for us to remind ourselves about the power that people have, the different kinds of power that people have. So on harnessing our autonomy, for example, people have tremendous powers as citizens and voters, as enforcers of transparency and accountability as litigators, even in the red state of Wyoming recently young people were able to take a court case and actually win a court case showing that the federal government was betraying.

Greg Dalton: it was Montana, but I know you're British, so geography's not so good

Kumi Naidoo: it is it was Montana. I've made this mistake before. I've made this mistake before.

Greg Dalton: One of those big square states, yes. It's all right.

Kumi Naidoo: Sorry, I've made this mistake before. This is Montana. But I want to just say that the second area which is harnessing our creative participation, and this is where I consider climate activism has made its biggest error, right? And that is, we have tried to shift people into action by science, facts, figures, policies, and proposals. Everything aimed at the head, and we have ignored the heart. Now I hate to say this. But Steve Bannon and Donald Trump actually get it. They get that you move people, not by facts, figures, and so on. And I'm not saying we need to do what they are doing, where they actually falsify the facts and talk outright lies and create alternative realities. We can stick to the facts, but we can communicate the facts in, hopefully, less of a boring way than we currently do it. We have to learn to move people and so yeah, it's about harnessing our arts and culture and so on. And I'll quickly just say that harnessing our wealth is a critically important thing. We have more power in terms of wealth, even amongst poor people around the world or low income people. If we aggregate, and we've seen this happen. Where people have gone in Australia, for example, when the wanted to do the biggest coal mine in Australian history in 2015, a coalition emerged, they mobilized people, they went to the banks every Saturday over a period of time and said, you will not lend to the destruction of our children's future. And all four Australian banks said, no, we won't do it.

Greg Dalton: There's lots of ways that people can be involved and we hear a lot about a just transition from away from fossil fuels needs to include communities, lots of talk, deliberation, consultation with Indigenous people. That sounds slow. What's the tension between speed and inclusion wen it means getting off fossil fuels. Are those things intention, inclusion and speed?

Kumi Naidoo: We need to be able to do both. We need to include people and we need to move much faster than we're moving right now If you think we're going to move faster by excluding people and so on Then we are making the wrong calculation because those people that have been excluded are going to hold you back

Greg Dalton: I hear Al Gore say, if you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.

Kumi Naidoo: Yeah, so you know, this is an African wisdom which i'll go always uses and I welcome the use of it.

Greg Dalton: Often without attribution, he does. Yeah.

Kumi Naidoo: But let me just say that the scale of the changes that we need to make to address the climate crisis requires a level of participation by ordinary human beings on this planet on a scale that we have never seen. And that doesn't mean we cannot move fast in doing that, right? Let's take the just transition which you should speak about. So if we are wanting to get the trade union movement to be a key partner In the fight on climate justice, which has been a big challenge.

Greg Dalton: Cuz labor unions love building fossil fuel pipelines and love –

Kumi Naidoo: But if I look at where unions were 20 years ago and where unions are today. Another story altogether and we have to acknowledge it. But and I think the time is right now to.

Greg Dalton: Although a lot of clean energy jobs are not unionized, there's still

Kumi Naidoo: Yeah, of course, there is a tension. Let me just tell you a thing that might shock you. The most powerful one liner on climate doesn't come from an environmentalist, comes from a trade union leader, right? At the Rio Plus 20 conference, 20 years after the first climate conference, I find myself sitting with 14 civil society leaders, including the head of the global trade union movement, Sharon Barrows, in Rio, waiting to go see Ban Ki Moon and Sharon is almost as naughty as I am so she, so we were looking at each other's notes, and she suggested, Hey, why don't you use my notes in the meeting with Ban Ki Moon, and I'll use your notes. And so there she was. As a trade unionist, speaking so strongly on climate change, you can see Ban Ki Moon is confused. He's like, why is this trade union lady banging on about climate? And then she says, Secretary General, you might wonder why me as a trade unionist, who has to focus on decent work, decent working conditions, and decent compensation, I am so concerned about the climate. And she said, because as a human being, as a trade unionist, and as a mother, I realize there are no jobs on a dead planet. There are no jobs on a dead planet. And I can tell you the whole room froze in a way that nothing that could have come out of my mouth could have actually done that.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a conversation with the internationally renowned activist Kumi Naidoo.

Coming up, Naidoo takes on the fossil fuel industry. And his approach… well, it was unconventional:

Kumi Naidoo: I shocked some journalists when I said, the men and women who work in the fossil fuel industry are our brothers and sisters.

Greg Dalton: Leading with empathy. That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: Please help us get more people talking about climate by sending this episode to a friend. Or take a moment to give this podcast a rating or review – we’d love to hear what you think, and it helps others find the show. Thanks!

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton

When we talk about change on a massive scale, the road to get there is inevitably going to involve some compromise. And I think that’s a good thing. For durable progress, we need more people saying yes, even if that means purity or perfection is not achieved.

When I talked with lifelong activist Kumi Naidoo, he explained that there’s another issue that is preventing the action we need on climate. He even describes it as a kind of disease…

Kumi Naidoo: The biggest problem in the world with disease we face is not COVID. Or any other disease, but it's a disease we can call affluenza. And affluenza is a pathological illness where humanity has come to believe that a good, meaningful, decent life comes from more, more, and ever more material acquisition. And the struggle on climate change has to be a struggle to rethink consumption patterns, right? We have become children in many parts of the world about how we've become dependent on all sorts of gadgets and symbols of achievement. When in fact, we should be incredibly embarrassed that so few have that when so many cannot, you know, even survive.

Greg Dalton: So how do you navigate yourself, your own personal complicity, you know, your own consumption, whether it's flying, et cetera. It's easy to say, like, Oh, I'm not a bad person. My little bit doesn't matter. And other people can obsess and get so hung up on tiny, tiny little things that have become paralyzed with their micro actions and they are weighed down and can't see the bigger picture.

Kumi Naidoo: So, When I was at Greenpeace, I used to get this question a lot, because evidently when I was at Greenpeace, I was one of the people that traveled most in the world, I was told. But if you take the entire budget of Greenpeace at the time, about, at that stage, about 300 million euro in global budget, right? And I'm up against 20 fossil fuel company leaders, right, right, who are flying in private jets to go to climate negotiations and so on, right. And, when we look at just Shell, take one company, their marketing budget, like our entire 400 million is not even 10 percent of the marketing budget, right? I was never going to be apologetic about using the only means of transportation sometimes that we had available to us to go and take on those CEOs of those fossil fuel companies. And so it's not, I mean, it's not like. I'm traveling, you know, lavish holidays on planes and so on. And, and, you know, I made choices and I, you know, you can check it out. I live, I live in a very poor community in South Africa where our government has destroyed our society. So I'm, I'm trying to live a low consumption lifestyle, use whatever money I earn for public purposes, and, but I'm not going to apologize for traveling to a space to fight a struggle that needs to be fought,

Greg Dalton: I understand CEOs, but how about rank and file workers? Because a lot of people here work for fossil fuel companies and hear environmentalists talk like, Oh, you hate me. You think I'm bad. I'm a bad person because I, I, you know, am working to provide energy that everybody uses every day. So can you parse the villainization of fossil fuel interests? Can you have some empathy for rank and file workers who are in West Virginia or Nigeria?

Kumi Naidoo: yeah So at the Paris Climate Negotiations in 2015, I shocked some journalists when I said, the men and women who work in the fossil fuel industry are our brothers and sisters. Right? They are not our enemy.

Greg Dalton: That's not an applause line at an environmental rally in Paris.

Kumi Naidoo: Yeah, no, no. People got very, what is he going to say now? But thankfully I say enough crazy things that people are used to it. So, so, I said, many of the men and women at the rank and file level who work We're told by the governments, by society, you are providing a critical service to make sure that this country runs. They want to provide energy. They don't particularly want to provide dirty energy, but they have not been given the option. And the beauty of if we get serious about a transition from an economy that's driven by dirty energy to an economy that's driven by clean energy is that if we get serious about it, the job creation possibilities, the pollution levels, a whole lot of, you know, things go down. I remember there was a cartoon at the Copenhagen 2009 climate negotiations where, you know, you had a bunch of people biting their fingernails and one person says to the other, What if we do all of this? And climate change was a hoax, right? And then, and then people said, well, that's air quality, more protected biodiversity and so on.

Greg Dalton: How do you, say, answer the question, is it too late?

Kumi Naidoo: Hey, shh! This one so, so, this is my line, but I must confess to you, not every morning when I wake up, I feel I can say it as confidently as I'm going to say it to you now. The reality is, we still have a small window of opportunity. So long as that window is open, we need to keep our optimistic take on it, right? But that window of opportunity is closing and fast closing. But, we have to believe that humanity can rise to the challenge and broaden that window and turn things around.

Greg Dalton: And good things are happening.

Kumi Naidoo: Yeah, and as you and others point out, it's happening too slow. So, yes, the main sort of rallying call that I'm promoting everywhere, and all the movements that I'm part of, where I say that in the moment of history that we find ourselves in, pessimism is a luxury. we simply cannot afford. And the pessimism that justifiably arises from our analysis, our observation, and our lived experience can, must, and should be overcome by the optimism of our thought, our action, and our courage. However, I said this once to some young people, and some of them confronted me after and said, Kumi, you know, that's all airy fairy bull* as far as we're concerned. But here's the science. We're almost getting to 1.5. And why don't you just say, we left it too late, and now we should just be thinking about how we survive. And then I say, well, that's not going to help us find the solutions necessarily. But let me just say, let me agree with you. That it is too late, right? and I, and I say to them, honestly, you know, there are times that I genuinely feel that.

Greg Dalton: For some people it's, it's

Kumi Naidoo: oh, of course for the, the, the, the 500 people that died in Durban two years ago in my own city, of course it was too late for them,

Greg Dalton: For a lot of people it is, yeah.

Kumi Naidoo: So I say. Assuming you're right, and we're all going down, I refuse to accept that those that brought us to this point will not be named, shamed, and held accountable for what they did to us, for those that didn't listen, for those like the Chevron, Texaco, and all these other companies, when their scientists were telling them about the dangers of fossil fuels before the IPCC and the United Nations were saying, and they were building their rigs higher in the oceans and so on because in they were taking into account, but publicly they were spending hundreds of millions saying, Oh, this is just a joke, right? And so when I say, I said, if we're going down, let's not go down without a fight, right? Let those that brought us to this point be held accountable. And if human life ever were to emerge again from this planet, then hopefully we can learn from that. And young people like the idea because it's hard for young people to find optimism in this current moment, right?

Greg Dalton: Young people are getting more confrontational, throwing soup on paintings, disrupting democratic politicians. What do you think when you see people gluing themselves to streets, disrupting, people who had formerly considered allies, moderate Democrats, making us all feel uncomfortable? Is that effective?

Kumi Naidoo: Before I comment on specific acts of civil disobedience by a relatively small number of people globally, I have to say, it's important that we actually name and identify the violence of the states, the violence of corporations, and what they are doing. Right? They are destroying all efforts. Right now, one of the worst statistics I can give you is, ten years ago, an organization called Global Witness, who does some really good work. They were measuring that we were losing two environmental activists every week, right? They now, the latest reports, we are losing four activists every single week, nameless to many, hidden from the view of the media, or ignored, but that's the reality. So, having said that, Activism has to also be looking at ourself and always saying, how can we be better? How can we shift people? How do we bring people on our side? And yeah, I think that, you know, let's take civil disobedience, which is what you focused on. Civil disobedience is one extremely important tool in the struggle for justice toolbox, right? Historically, what we know is that when people face terrible injustices or challenge, it was only when decent women and men stood up and said, enough is enough, I'm prepared to go to prison, I'm prepared to give my life if necessary, that change came. And that's the moment where we are. However, having said that, you know, civil disobedience is a very contextual thing, right? And like any tool, you have to use it strategically. And if you overuse it, it can also get planted. So let me ask you a question here. How many of you know what's mooning? Mooning? Okay, so mooning, okay, most of you don't know. I never thought I would be educating Americans on mooning. But let me, let me try. So mooning is if, say, ten of us want to make a poster saying, Stop climate change, but we couldn't get our posters into the meeting. We would each paint one letter on our bum cheek, and then we'll pull our pants down, turn around, and they'll say, Stop climate change. Now, that might be super effective in New York and in San Francisco as a strategy. It might not work that well in Saudi Arabia or Indonesia, for example. Or for that matter, Montana, right? But we have to give Montana credit for having got that good legal decision. So, so, so I think, you know, also what you need to be, the number of incidents where people went and, you know, put their things on paintings and so on. By the way, mostly with things that could easily be cleaned and not long term damage. It's the privileged elites of our society in the media and so on went bonkers about it. But they control the media. And therefore, I'll just end by saying why programs like this are so important, like Climate One, is our biggest challenge we face. It's not whether we got the right policies and the right, uh, you know, specific technical strategies. The biggest problem we have is that we have a media environment that we operate in. Like the United States, where close to after people get one reality from Fox Newsmax and right wing talk radio and the others get a different perspective and the bottom line is to advance climate justice, we have to address the issue of communications, and how can we talk to people that moves them into action.

Greg Dalton: And do you think that climate philanthropy recognizes that? Because what I see is a lot of climate philanthropy is focused on policy, policy, policy. They underinvest in communications, which you just, you said Steve Bannon and Donald Trump understand communications and the narrative and the left is saying, oh, but science, oh, science.

Kumi Naidoo: So, without naming any foundations or anything, let me say thankfully there's some new kids on the block who seem to get it, right? And you know, uh, that we have to invest there, but I want to be blunt here. In the United States and globally, we don't really have that much philanthropy. We have mostly fool anthropy, right? Where we are fooling ourselves that we're making a difference, where we are using resources in ways that are not courageous enough, not strategic enough, and so on. Because how do people move into action, move to do things, right? And here I just want to conclude this point by saying people like myself must also take, uh, responsibility for the kinds of personas we are allowed to be projected. Lots of people see me as like a serious committed, hardworking, overworking person, right, who is like always 24 seven. That's not the image we want to send to people. We need to send the thing. You can be an activist and you can live a life and you can make change. And most importantly, as Secretary General of Amnesty International, when we gave the Ambassador of Conscious Award to Greta Thunberg and Fridays for the Future, these are the words I said. You know, I said, The thing that hurts me, right, is that your generation, these kids generation, have to do so much. And I apologized for the, our failure as a generation. And then I said, but please do us one favor, execute your activism with fun, sing, dance, laugh, celebrate each other. And unless we're able to encourage people to have a positive feeling about activism, right? We don't stand a chance.

Greg Dalton: So too much focus on facts. More heart, more stories. You’ve promoted what you refer to as “artivism,” and written that “Mobilising the power of arts and culture may not on its own deliver justice, but without it, our efforts will surely fail.” So talk about the importance of artivism.

Kumi Naidoo: So, I think most of you know that in history, arts and culture has been used very, very effectively by fascists and Nazis and so on, right? So I don't want to say arts and culture by its very nature is always progressive, but let me do a quick story on it, Iceland, right? I'm the Secretary General of Amnesty at that time, I get a call from one of the most amazing artists in the world, a guy called Olafur Eliasson, uh, who's from Iceland, and he calls me, he says, Kumi, can you please come to Iceland? And he says, can you please bring Mary RobinsonSo I said, what's happening in Iceland? So he says, no, we're having a funeral, right? You need to come for this funeral. And then I say, oh, I'm really sorry, who passed away? And then he said, an iceberg, right? And Mary and I went, and we stood with the prime minister of Iceland. And about 500 people go up this dead iceberg, and there's a plaque there which says something like, you know, we know what we should do at this moment in history, and if you're reading this plaque now, it means that we probably succeeded at something better than what I just said. But do you know, the impact of that event was a thousand percent more effective than 90 percent of the actions that I did while I was at Greenpeace. the way it actually moved people.

Greg Dalton: I saw a very powerful one in Egypt where doctors stood up in white coats inside the conference and they said, my patients are dying from climate impacts. And then that, that clinician lied down on the ground. It was very powerful to see clinicians one after one saying the people I've taken an oath to care for are dying from climate impacts that they did not cause.

Kumi Naidoo: And let me just say, you know, we, my better half Louisa is here with me, and we had a. terrible tragedy when our son took his life, uh, two years ago. And in the last conversation, he was a very successful hip hop artist and, uh, rapper. And the last face to face conversation I had with him, he basically, that Louisa and I had with him, he said something along these lines, you know, you guys, you're not really good at what you do. You've all been fighting for democracy, human rights, climate, and so on, and everything is going in the wrong direction, right? So maybe you should just chill. You're old now, just chill, spend more time with us, and, and so on. But what that's encouraged us to continue doing is to look at. Because he moved millions of people through one song, you know? Millions of people, you know? And made them feel good about themselves, made them feel positive and so on. And so, of course, I should say that he was really pulling our legs a lot. He didn't necessarily literally believe what he was saying. But what's clear to me right now, If we don't harness the full power of arts and culture as part of reaching people, moving people, and if we look at the history of struggles all over the world, right, including the anti apartheid struggle, you know how central arts and culture was to our struggle because most of our people were not able to read and write. And that was a conscious design of the apartheid state, right? And so, I remember in my teens, one of the campaigns, in a working class, communities, was when things were really bad. Depression, cost of living, everything. Just one big Zulu word in English, three words, was what communicated the whole message. Asinamali, which meant, we do not have money. Right. But sometimes the simplest words are the ones that can move people rather than coming up with terms like LULUCF, which stands for land use, land use, change for forestry, a very, very often quoted thing at climate negotiations.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, we're good at jargon in climate world. You're now writing a book, Reflections of a Failed Activist, what are your greatest failures and successes?

Kumi Naidoo: So, firstly, I just want to say, right, had all those that have been part of the world of activism not done what they did. Whichever place you were, whether you were at the YMCA, or whether you were at Greenpeace or Amnesty, had all of that not happened, the world would be in a much it would be a time up for climate. Long time ago, we would have lost on climate.

Greg Dalton: We've made a lot of progress. Some progress. Not enough, but we've definitely made some.

Kumi Naidoo: Well, I don't know whether I would put it as strongly as that. I would say that we, we, we've been holding the wall from crushing us, right? We've been pushing the wall back and we've held and contained it a bit, but. I cannot tell you how much of time we have all spent in what young people now dismiss as handshake activism. You know, going in good faith and meeting with UN bodies, CEOs of big companies, uh, and, and, you know, it was a ritualistic exercise. What would happen was, I would go into, like, say if I was meeting with the President of Afghanistan, for example. When I go into that meeting, I pretty much know what he's going to say to me. He pretty much knows what I'm going to say to him, right? He ticks off a box, civil society consulted. I tick off a box, government advocated upon, and nothing changes, right? Now I'm, listen, so I'm, I'm caricaturing here, right? I'm not saying as a principle, we should never engage with government and business. But at some point we have to look at what's the return on that investment and it doesn't look good at all, right? And so, so I don't know the answers to what the solution is, right? But I do know that all struggles are dependent on the participation of people who are impacted.

Ariana Brocious: That was the activist and climate leader Kumi Naidoo. Coming up, when it comes to addressing climate chaos, we’re all in this together.

Tamara Toles O’Laughlin: The youth agenda is no different than the Black agenda than the Indigenous agenda. Because at the end of the day we need to be in a space where we can move the needle for change because there is no separation of success here.

Ariana Brocious: How to join forces… That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious. We like to explore many different kinds of activism on the show and the power of culture to affect change. Sometimes this iscalled “artivism”: combining art with activism.

Greg Dalton: And for the show with Kumi Naidoo, I invited a young poet to join us on the stage. Her name is Alex Ajose Nixon – and she’s just 17 years old.

Alex Ajose Nixon: What should be the goal of humanity? Everything is just a mess, I mean, Fracking factories and oil spills overseas No one says thank you or please unless they're spreading the disease Of spoiled brats who waste everything While others are praying on their knees Everything is for money these days And there's no space for the games we played The idea of fun is funny to say But bombing foreign countries Yeah, that's okay There's so many people that aren't thriving and so many people that aren't trying and dude you gotta open your eyes cuz look around everything's dying.

Ariana Brocious: You can hear her full poem on our website – we’ve got a link in our show notes and at climate one dot org. And wow. The power of words.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, it made me question. Am I doing enough? Am I lying to myself? Am I lying to my children? What are we doing here, people? And her performance reminded me of a conversation I had a couple years ago with Hip Hop artist and educator Mystic.

She’s one of the clearest thinkers I know about the power of art. And she speaks from decades of experience, as an artist with Digital Underground and as an activist and educator with the Hip Hop Caucus.

Mystic: Art plays in its many different manifestations, right. It plays this role of opening up pathways for communication and understanding. It helps to shift the culture that is felt in the community, in the room. It can help shift the culture in the context of legislation and policy makers. Art allows people to tune in, right. I think sometimes when we’re enjoying ourselves or engaging with art, some of our defenses come down. And particular for me as a music artist music is a universal language, right. I've had the privilege to study in South Africa and to work with children in Haiti and children and youth and indigenous youth in Canada. And you know children in various parts of the nation and part of what I know is that people sing along to songs whether they understand what the words are saying but the art itself is a bridge. It helps to build a bridge across man-made borders and the beautiful variety of cultures that exist. Art is also the voice of the unheard and the excluded if we’re using it right, right? And if we understand the power of what that art is. Art has this unlimited power to open up conversations so that we can work collectively. I also understand having engaged in research on culturally relevant arts education that because it's so powerful people can also use art to kind of subvert the will of the people and to push forward, you know, authoritarian messages, so we have to be careful, and we have to understand that art can be powerful no matter who is using it.

Greg Dalton: Traditionally most science communication and this includes a lot of climate communication follows the information deficit model. If we just give people more information, that's what's needed to affect change. And then there are sort of the empathy or emotional deficit model: if we can get people to feel more that will prompt action. I’m curious how you think about this as a musical artist and now you’re involved in film, that emotional connection versus, you know, do you need to get people to feel more or know more?

Mystic: Right. There is so much information that's hitting us from all angles in where we are, right. Whether it's via social media or the radio or in our communities, we’re constantly being bombarded with information and that can be an overload. Scientific research and when it's presented in this kind of, we need more information, the understanding that information is not guaranteed. It's not that people lack intelligence. It's just how do you take that science and that data and apply it to your everyday life and what you're experiencing. Like what does that science and data mean when your community floods even on sunny days, right. And so, I think that part of the power of music and film and just creativity and culture is that, that is about connecting on an emotional level, but you also have to take an approach like look. Typically, my verses are 16 bars. I can't try to fit in there the science, right. As academic I can actually read some of those scientific documents and the data.

Greg Dalton: There’s no footnotes in your lyrics, right?

Mystic: Right. There’s no footnotes in my lyrics. But it’s figuring out I don't just create my art for myself it's about communication art. And so, I think in some ways it's equally if not more powerful than just offering more information that is in the form of data and scientific language when you can use art. More people can connect with that they can gravitate to it and it can be cool and it can make you move and it can make you understand in a different way what's happening. You know when we talk about the climate movement or the environmental movement more broadly, the movement there have often been disconnects between the crisis that we’re facing and what's happening. And then how do we create information and knowledge and resources that is culturally relevant and responsive in ways that the communities that we want to communicate with can receive what we’re trying to say, right.

Greg Dalton: How do you know if your art has any effect, it can emotionally connect but how do you know if it causes change and do you have any specific examples of when art has really changed someone's mind or really had a tangible impact?

Mystic: I probably have more than we could talk about in the space of this conversation. I have fans across kind of areas maybe that people wouldn't expect, but people who are police officers and people who work in government as well. And they too will have conversations though maybe ask me and challenge me about something I’ve said or say, hey, I'm not that kind of person, right. But that they've come to me and said that listening to my music has given them ways different ways to think about our communities and to think about the ways that they serve. And maybe it's not the art itself but being an artist and being nominated for awards, it might not be the music but it's my platform that gets me into the room to speak with politicians that gets me into the room to be able to speak to what is on the table in terms of legislation and the importance evident to advocate for what our communities need.

[music]

Ariana Brocious: That was Hip Hop artist and educator, Mystic. You can hear more of that conversation by going to our website, Climate One dot org.

[music starts to fade]

There are lots of ways for activists to find their audiences. Some make music… some interrupt meetings, or glue themselves to runways.

Greg Dalton: Those people don’t speak to me personally, BUT I do see their desperation that comfortable elites are not going to make the required change in the time necessary. We gotta all move faster, and wake up.

Ariana Brocious: As things get more dire, I think more people feel like this sort of disruptive action is necessary. One question I have is: how do we measure the effectiveness of that action?

Greg Dalton: One person who’s done actual research into the effects of more confrontational activism is Sociologist and Professor Dana Fisher.

Dana Fisher: Confrontational activism has gotten much more common. It also has kind of broken into what I think of as two different camps in terms of disruption. So, we have disruption like the people who threw food, threw paint, used crazy glue. And that’s the kind of disruption which I'm calling disruption as shock. And that is becoming increasingly popular and we see it all around the world at this point targeting art, targeting meetings, targeting performances. In all those cases, the goal of that tactic specifically is to get public attention. And they want to basically reach out and try to mobilize more people in the general public, what they think of as you know, sympathizers to the movement.

Greg Dalton: But when those sorts of things happen I have to wonder whether they repel more than they recruit. That it turns more people off than it wakes people up.

Dana Fisher: Well, I mean I think the expectation here and the research backs this up is that it will not change minds. This is really a type of activism that’s about taking people who are already sympathetic to the cause and you're getting increasingly worried because of atmospheric rivers or because of forest fires or because of this extreme weather that's been happening in Europe or the melting, you know, glaciers, or the list goes on and on, or, or, or. And those people think they need to do something but they haven’t yet mobilized to do anything. That’s really the point for these activists, and in a lot of ways they use what we call the radical flank effect to push the activism to a more extreme place that mobilizes people to be more willing to participate in moderate types of activism and support for moderate groups. And there's a lot of research that documents that that works that way.

Greg Dalton: Right. We know that there’s what 9% of Americans are sort of hard-boiled deniers. There’s a big group in the middle that accepts climate change is happening according to the Yale’s Six Americas is probably the most authoritative poll on this. And so, what I’m hearing is it’s those people who say, yeah, climate change is happening, it's real, but aren’t really doing much about it. It's about activating that disengaged part of the population.

Dana Fisher: That's exactly right. I mean I would just say within that middle group. I think that most of the people who are engaged in this more destructive type of activism are really looking for the more left-leaning of those group; they're not even trying to get all the moderates. They’re trying to get the moderates who supported the passage of the IRA, but they are worried that it's not enough. Those people. And the idea is to bring them into the movement and to support more climate action and more extreme measures to get to the kind of climate action that's necessary. That's the only audience for this type of action.

Greg Dalton: Political movements are focused on goals that can be specific: oust a dictator stop a war, overturn a Supreme Court decision and less specific in conceptual justice equality, etc. In the case of climate there are very specific numbers overarching numbers 1.5 or 2°C of postindustrial heating and many sub-goals, of course. How do you see the goals of the transition away from fossil fuels in the context of other social movements?

Dana Fisher: I would just say that the climate movement is really very, very similar to these other movements where there are these grand goals these big goals, you know. Climate justice, you know, achieving the Paris goals, which is actually a more specific goal than just climate justice of course, which is just transition away from fossil fuels toward a clean energy future. We see the same thing in other movements. And in fact, I think that because there's so much science backing up the climate crisis, the climate activists are more capable of embedding these broader goals within more narrow campaigns. The big question you know in a lot of my work is how do we get from these activist tactics to those goals which in some cases are so far away from the actual tactics and the targets of the activism. Say, for example, when Declare Emergency had activists spilling paint covering of this Dégas statue. How exactly does that lead us to reducing CO2 emission concentrations in the atmosphere to the degree that we actually hold global heating below 1.5°C? That's a very, very, very big, big arc to get there. And, you know, it goes through public perceptions to theoretically getting public pressure to then electoral politics that then theoretically leads to elected officials actually voting in a way that they say they will when they run for office which we all know is you know a question whenever you support somebody, to that whatever they support getting actually passed and implemented effectively and then might lead to these goals. And so, it’s such a long and indirect road.

Greg Dalton: Right. And which is why people might choose other more direct things that is not either/or, but you know if I take personal action, switch out to a heat pump or something like that. It’s like I know how much that's done. It doesn't solve the big picture, but it's more direct control.

Dana Fisher: I would just say that’s absolutely true. One of the things that I've talked a lot with climate activists about is the types of individual measures you can take simultaneously. But as somebody who spent a bunch of time studying this and working with the IPCC on this, we now there is overwhelming evidence that just our individual actions like we just put solar on our house is absolutely insufficient for getting us where we need to go.

Ariana Brocious: That was Sociologist and Professor Dana Fisher. She’s got a new book out now called “Saving Ourselves.”

Greg Dalton: Saving Ourselves: It’s not something any of us can do alone... But there’s real power in the collective. I want to close the show today with Tamara Toles O’Laughlin. She’s President and CEO of Environmental Grantmakers Association and former Director of 350.org North America. She describes herself as an advocate for the People & the Planet.

Tamara Toles O’Laughlin: We’re in a moment where we’re all pushing for the same thing at once. Energy needs wisdom and vice versa and so we are in a time when the youth agenda is no different than the Black agenda than the Indigenous agenda. Because at the end of the day we need to be in a space where we can move the needle for change because there is no separation of success here. We’re in a time test as Bill McKibben likes to call it. And I assure you that at the end when the buzzer is up, we’ll all be in the same boat so we might as well be running in the same direction.

Tamara Toles O’Laughlin: My gut is politicians only do we give them room to do and what you give them cover for. So, our politics are only as bad as our engagement. So, at the end of the day if you don't like what's happening you can push the button and make them move away. And if you want them to do more you can get out on the street and create an agenda for yourself. We are no longer in a time where we need a proxy, we set up proxies to make the work happen. So, I do think look in the mirror and figure out how are you willing to go to get the world you want to live in and who you else you need to bring along with you because there is no such thing as alone will save us from climate.

Greg Dalton: On the show today... We’ve been talking about how activism can win bigger and faster. You can find links and more information… in the show notes on our website, climate one dot org. While you’re there, subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get a preview of next week’s episode and a look at the biggest stories in the world of climate.

Ariana Brocious: Talking about climate can be hard-- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. You can help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really helps people find the show. And if you like what you hear, consider joining us on Patreon and supporting the show that way.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Ariana Brocious is co-host, editor and producer. Austin Colón is producer and editor. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Wency Shaida is our development manager, Ben Testani is our communications manager. Jenny Lawton is consulting producer. Our theme music was composed by George Young. Gloria Duffy and Philip Yun are co-CEOs of The Commonwealth Club World Affairs, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.