The 2020 Election: Anxiety and Incrementalism

Guests

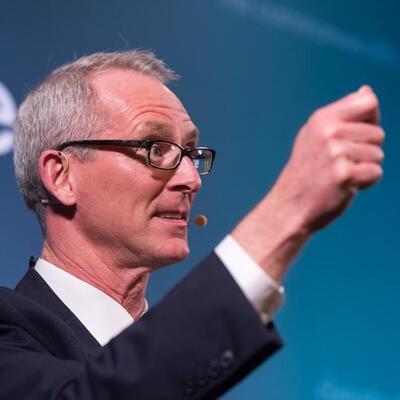

David Roberts

Renee Lertzman

Eric Utne

Summary

The 2020 campaign season has finally come to a close. And days after November 3rd has passed, the country is still reeling.

About seventy percent of Americans - Democrats, Independents and Republicans - say the election caused a significant amount of anxiety and stress in their lives. That’s up from fify percent four years ago.

How should we process those difficult emotions surrounding the election? Climate psychologist Renée Lertzman recommends practicing self-awareness and self-care.

“It’s very important for us each to know what our own thresholds are,” she says. “So knowing when it's time to sort of disengage and to take care of ourselves. To do what we need to do to restore our sense of being grounded, of being connected, of being in balance. So definitely, it’s a balancing act.”

With so much at stake, hopelessness might be seen as the default.

“I like to say that I'm not hopeless, I'm hope free,” says Eric Utne, founder of the counter-culture magazine the Utne Reader and self-described “recovering hope junkie.”

He goes on to explain the distinction:

“When I think about being hope free, it’s not despondent and despairing” Utne says. “It's realizing that there's another choice.”

As a divisive election drags on, what are the prospects for confronting climate disruption? Some of the biggest advances for Republicans came in areas experiencing climate impacts. Democrats lost House seats in Oklahoma and New Mexico in districts dependent on fossil fuels. And the day after the election, per Trump’s edict, the U.S. officially withdrew from the Paris Climate Accord.

David Roberts, climate and energy reporter for Vox, believes that a President Biden would waste no time getting us back into the agreement.

“That's the one, I mean the one clear I think good outcome of this that people can hang their hat on,” he says, “is the president has a lot of power and latitude in foreign policy…So, there's a lot Joe Biden can do on foreign-policy to get us back in Paris. He can start you know, drawing together small groups of nations that are willing to move faster. He can pressure Brazil to stop burning its rain forest, things like that.”

Regardless of the outcome, Lertzman prefers to see the 2020 election as a beginning, rather than an ending. “It's a gateway into a deeper way of doing our climate work and our politics and our educating and our innovating and all of that -- all of these activities that we’re needing to do right now.”

Related Links:

What happened in 8 state energy battlegrounds (E&E News)

A second Trump term would mean severe and irreversible changes in the climate (Vox)

Project InsideOut

Utne Reader

Far Out Man: Tales of Life in the Counterculture (Eric Utne)

Environmental Melancholia: Psychoanalytic Dimensions of Engagement (Renée Lertzman)

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

About 70 percent of Americans - Democrats, Independents and Republicans - say the election caused a significant amount of stress in their lives. That’s up from 50 percent four years ago.

Renée Lertzman: How do we really pay attention to those fears and anxieties? [:04]

Greg Dalton: And people worried about the climate have even more to worry about now, after election results that rebuffed some voices for cleaner energy.

David Roberts: slow action leads to three to four degrees of warming, which is extremely not good. [:04]

Greg Dalton: On today’s program, we’ll talk about difficult emotions brought up by the contentious and divisive national election happening amid rising climate disruption. With so much at stake, hopelessness might be seen as the default. But some see a distinction between being hope-less and being hope-free.

Eric Utne: When I think about being hope free it’s not despondent and despairing. It's realizing that there's another choice. [:08]

Greg Dalton: Election anxiety, hope and grief. Up next on Climate One.

---

Greg Dalton: As a divisive election drags on, what are the prospects for confronting climate disruption?

Climate One conversations feature all dimensions of the climate emergency, the personal and the systemic, the exciting and the scary. I’m Greg Dalton.

Later in the show we’ll hear from psychologist Renée Lertzman about self-reflection and empathy in the wake of high stakes elections. We’ll also hear from Eric Utne, founder of the Utne Reader, about his surprising approach to hope.

First, a quick take on the election.

Greg Dalton: The path for climate action is narrower now in the United States than it seemed a few weeks ago amid talk of a potential blue wave opening up new possibilities for moving to cleaner energy.

Some of the biggest advances for Republicans came in areas experiencing climate impacts, according to reports from Climate Wire and the New York Times. In Miami, voters ousted two democratic house members. Donald Trump improved his vote in that democratic stronghold that is experiencing sunny day flooding related to rising seas that are caused by burning fossil fuels.

Charleston, South Carolina is being hit by rising ties, and voters there ousted Democrat Joe Cunningham in favor of Republican Nancy Mace, who says that climate science is unsettled.

In Texas, Democrat Chrysta Casteneda received $2.5 million from Michael Bloomberg as part of his climate campaign. But Casteneda appears to have lost her bid to serve on the Texas railroad commission, the state's powerful oil and gas regulator.

Democrats also lost House seats in Oklahoma and New Mexico in districts dependent on fossil fuels.

There were a few slivers of light for people concerned about climate.

Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), Ilhan Omar (D-MN), Rashida Tlaib (D-MI), and Ayanna Pressley - all strong supporters of the Green New Deal, won decisively.

Denver increased the local sales tax to raise money for efforts to reduce the city’s greenhouse gas emissions.

In Nevada, voters affirmed a state initiative requiring half of their electricity come from renewable sources by 2030.

Add it all up, and the election didn’t accelerate a transition to cleaner energy, although markets, technologies and companies are all reducing carbon pollution.

To make sense it all I turned to David Roberts, who covers energy and climate for Vox. We spoke as he was still processing the election results, like everyone else. He wondered what it would take for Americans to fully realize the magnitude of a disrupted climate.

PROGRAM PART 1 - DAVID ROBERTS

David Roberts: Well, I think the climate community doesn't necessarily like hearing this but I just don't think climate was a particularly salient factor in the elections this year. There's too much else going on. There's too much chaos. And I think what we learned is what we keep learning over and over and over again what I personally keep learning over and over again. Every time I think I've learned it I learned that I have not learned it hard enough which is just that polarization is the strongest force in U.S. public life now, nothing is stronger than it. And we have sort of like this almost sort of like ludicrous case study like what if a president came in and allowed a quarter million people to die like what if there was the greatest mass casualty event in U.S. history on a visibly, you know, sort of incompetent president’s watch. It didn't move the poll numbers at all like the Biden-Trump poll numbers were not dented at all by these catastrophic historical events. And I think that's just what you see up-and-down the ticket is just that with just sort of very, very, very tiny moves along some margins basically the sides are set and it appears that literally nothing can break through that.

Greg Dalton: And you've written about this how people sort of process information and make decisions whether it's election or what information to accept based on tribal motivations, queues from social elites. So, does not just makes sense that people, a quarter million people died, but my family, my tribe, my people have this narrative about that that it's not his fault that it came from China. And that just, you know, we, we’re not rational beings we’re tribal animals.

David Roberts: I just think that something like, and especially people of the liberal temperament. Let's say the sort of your standard highly educated, highly verbal, liberal arts trained liberal wants to believe even though I think liberals have come to acknowledge the sort of basic irrationality and this basic sort of like social determinism in the U.S., I think they still want to believe on some level that it has limits, that there is some edge, some limit to it something that could happen that could break through it people really want to believe. And I feel like now like if a pandemic that kills a quarter million people and is very clearly one party's responsibility. If that can't do it then I think we have to acknowledge that literally nothing can. There's nothing climate could do could break through that.

I mean these people, they are also the ones dying, their communities are dying. It's worse in rural areas right now, the virus, than it was, you know, a few months before the election. And it just didn't change anything. It’s just hard to imagine what could change anything. So I think the conclusion for the left has to be at least for the time being, you're not going to, you know, like there's stuff you can do to change numbers along the margins, but the big problem is just the structural features of U.S. government exaggerate the power and the voice of Republican constituencies. And so even though they have a minority, even though there are more Democrats you know like everyone knows Joe Biden's gonna win the popular vote by a pretty big margin, it’s just common knowledge now, there are more Democrats. It's just the system is set up so that the minority of Republican constituents have a lock on the structures of the U.S. government. As long as that's in place I think we’re just in for spinning our wheels like this for forever.

Greg Dalton: During the election there was some discussion of energy. There was the talk about Joe Biden's comment during one of the debates about transitioning away from fossil fuels. That created quite a stir. Even though polls show that American support that, Americans support moving towards clean energy, etc. until you put a price tag on it or there's a personal impact. So, tell us your thoughts on that on how the debate around climate change energy in the election and how that played out.

David Roberts: Yeah, I think if being honest I think most of that was a bored national media wanting for there to be something to say or write about. Because I mean one of these things about partisanship being so frozen and the respective candidates’ numbers being so steady and frozen no matter what happens is it gets very boring as a political journalist. I mean the question is like will this gaffe or this incident or this little thing affect the race. The answer is just always no it won't.

I don't think I honestly don't think energy play that huge of a role in the election or in the election results. I don't think any substantive policy related discussion did. We’re in a level way deeper than that now. We’re like identity, gut identity level, basic values level. Like policy is just sort of the least of everybody's worries at this point. So, you know, and on the larger point of like how the public thinks about energy is just I tried to get at this in a post the other day is just the general public by and large, and this something political scientist know but like can’t seem to persuade everybody else to take seriously is that the general public doesn't know anything. They have lives, jobs, worries like sports and TV shows to watch like they just don't have time to keep up with politics. And so, they just don't have substantive views on issues as such. Their views on issues are very shallow and often self-contradictory and often just pull together scraps of information that have managed to make it to them. And so, they're very malleable so you can push them easily either one way or the other.

So, if you talk about energy in terms of cleanness and lack of pollution in like the future and innovation, they’ll give you positive poll responses. And if you emphasize, oh, a cost, a penalty, some sort of restraint on your life or lifestyle you’ll get a negative poll result. But there's no deep conclusion to draw from either of those.

Greg Dalton: In this program we’re exploring election and climate, anxiety, grief and hope. Some experts, including psychologists Renee Lertzman in our next segment say that after divisive elections people on both sides should like inward and someone compassion for voters who see things differently rather than ridiculing them to listen and seek to understand. Your Twitter feed is full of strong statements about people who don't see climate the way you do. How often do you reflect on your own tone and seek to understand people who are not as concerned about climate as you are?

David Roberts: You know, maybe it's just the mood I'm in today, which as you can probably tell is not a good one. But to me there's something so characteristically left about losing and then spending the period after losing telling one another that losing isn’t really so bad after all and let’s be nice and let's feel compassion for the people who just destroyed us and want to destroy everything we care about and want to roll the country back centuries. And want to do nothing about climate change and want to put refugee kids in cages and want to, you know, bring in federal troops and beat protesters. Yeah, if we compassioned them a little harder, you know what that would do, it would make us feel good. And it would make us look good to one another, but the alleged targets of the compassion don't give a damn. They just want us dead and they never pretended otherwise.

Greg Dalton: Several years ago, Trump announced his intention to withdraw the United States from the Paris Climate Accord and the day after the election that officially happened. U.S. had already stopped pursuing Paris pledges and today the country is roughly halfway to the Obama era reductions in carbon pollution. Europe has stepped up with more ambitious goals. But how big a deal is this that U.S. is now out of Paris?

David Roberts: The U.S. will get back in Paris if Biden wins as it sorts of mostly looks like he's going to. That's the one, I mean the one clear I think good outcome of this that people can hang their hat on, is the president has a lot of power and latitude in foreign policy, more so than on domestic policy. So, there's a lot Joe Biden can do on foreign-policy to get us back in Paris, he can start you know, drawing together small groups of nations that are willing to move faster. He can pressure Brazil to stop burning its rain forest, things like that.

So, on foreign-policy there is, you know it's good but ultimately the U.S. can't lead on this if the U.S. isn’t acting on this, right. I mean there's only so much you can do with words and plus now all our international partners like well whatever you say Biden, for all we know in 2024 you’re gonna flail back the other direction and the next president will undo all this. The international community can trust U.S. intentions and steadiness less and less and less, which is just bad. I think unequivocally bad for the global climate effort. As much as people criticize the U.S. and US foreign policy. The U.S. is about as good as it gets in terms of who can play a leadership role in this international effort who has sort of the power and the money and the influence, the soft influence and the hard influence, to lead these things in the right direction. I don't think the E.U. is gonna be able to do it and I don’t think we’re gonna much like the way it looks when China is leading the effort. But at least on foreign-policy there's a chance now to sort of send a different message to the international community, but ultimately like things are moving in the right direction too slowly.

This is the big story of climate change, right. I mean everything is moving in the right direction. Clean energies rising public opinion is changing very slowly policy is changing across the world it’s changing in cities, companies are coming around big companies like things are moving in the right direction just much, much too slowly. And what this election was, was a chance to speed them up substantially. And now I think that chance is lost and as you know, slow, slow action leads to 3 to 4° of warming which is extremely not good.

---

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about the 2020 election. We’ve been talking with David Roberts, Energy & Climate Change Writer for Vox. Coming up -- when it comes to dealing with difficult emotions surrounding the election, climate psychologist Renée Lertzman recommends practicing self-awareness and self-care.

Renée Lertzman: So knowing when it's time to sort of disengage and to take care of ourselves, to do what we need to do to restore our sense of being grounded, of being connected, of being in balance. So it’s definitely a balancing act. [:18]

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about election anxiety, hope and grief. My next guest, Renée Lertzman, is a psychologist who works with the messy emotions of climate change. When we talked a few days ago, campaign season was reaching fever pitch, with most polls showing Joe Biden in the lead. I asked Dr. Lertzman how she responded to Donald Trump’s surprise victory in 2016.

PROGRAM PART 2 - RENEE LERTZMAN

Renée Lertzman: Well, at the time I thought okay now we will finally get it. That there is a profound and deep sense of pain and people feeling aggrieved people feeling left out to the point where we would see what happened with the election which is, you know, a behavior that just seems really counterintuitive, but people coming from a place of fear. I thought now we will get it and we will start to change and we will engage in a deep reflection as a community as a climate community as a climate sector as a progressive community. And looking back, I think that I underestimated the profundity and the real dedication that it would take for us as humans and particularly those of us who were caught off guard and shocked to do the hard work the inner work quite frankly of really looking at ourselves and looking at how am I showing up and how am I pushing myself out of my comfort zone. So that I'm willing to truly listen to engage to be curious about the experiences of my fellow Americans, and my fellow humans. I think I just didn't really take that quite, you know, on board enough. And looking back I wish that I had kept the attention on that more consistently.

Greg Dalton: The election of Donald Trump I’m hearing you say presented an opportunity to kind of lean in to talk to people to understand what fear or anger motivated their vote. So, what are you thinking about as we head into, you know, as this election is being counted and decided, have we learned our lesson? What are you thinking about now in terms of the opportunity after this election to do what we didn't do last time?

Renée Lertzman: Well, what I'm thinking about is how when the stakes are so high and we care so deeply about the outcomes is precisely the hardest time it is to show up in the ways we’re needing to. So its sort of the ultimate human paradox that the more heightened the more fear the more anxiety. Those are the conditions that actively make it hard for us to move into what I think we kind of know we need to be doing, which is what we sort of give lip service to. Which is more listening, more empathy, more relationship building, you know, healing across the divide all of that. That's what I'm really aware of. And the way that I frame this is really as a truly human developmental opportunity that we have this opportunity now to unfortunately through pain, you know, which is usually the impetus for change is discomfort and pain. That we have the opportunity to allow that to really change us and to move into ways of being and relating that are different that actually require us to listen to pause to be curious.

But the other really important aspect of this when we’re talking about anxiety and high-stakes is that we need each other right now more than ever to help us kind of stay in that place of being what neuroscientists would call regulated. Like when we actually are able to self-regulate and stay grounded to stay balanced to stay responsive versus reactive that we need each other to be doing that. And in my experience, you know, really the only way we can do that with each other is by being able to name and acknowledge what's actually going on. To be able to speak about and normalize the experiences that we’re having, you know whether it's anxiety, fear, overwhelm, sadness and, you know, inspiration and motivation all those other things too.

Greg Dalton: But how do we know that getting together might just fuel that anxiety. Sometimes I get together with certain people and they gripe and I’m feeling like, oh, this is making me more anxious, maybe I’m getting together with the wrong people. But it’s making me more anxious when people who all agree kind of kvetch and they talk about one candidate or another and it just seems like, whoa, this is not soothing.

Renée Lertzman: [Laughs] Good point. I think that's the dark side when we get together and we talk about our feelings. But I think there's more of a phobia about if we start talking about our feelings where you just gonna sort of get mired there. What often can happen is the opposite is that when I share this is what’s up for me, I’m feeling anxious and overwhelmed. What often does happen is that we tend to move into a different mode of okay now what do we want to do. How do we want to proceed? We tend to kind of move through it more often than not.

I think that it's also very important for us each to know what our own thresholds are. So knowing when it's time to sort of disengage into, you know, take care of ourselves to do what we need to do to restore our, you know, a sense of being grounded of being connected, of being in balance. So, it's definitely it's a balancing act.

Greg Dalton: Joe Biden said during one of the debates that we need to transition away from fossil fuels. Something that is actually supported by polls that show that 80% of Americans support getting 100% of clean energy in this country. So it's a popular statement yet so many people still there's fear that so much of this climate conversation is driven by fear of us losing something, our hamburgers, our airplane flights, our comfortable cars whatever it is. Is that contrived fear or is that real fear underneath?

Renée Lertzman: Well I think it's incredibly important to situate any kind of change any kind of transition. It's going to evoke anxieties and fears with people like that's just a given. I think that for those working within the climate sectors and movements it's easy to overlook and to forget that what we’re really talking about when we talk about fossil fuel transition is incredibly profound. And that it really touches virtually every aspect of who we are our identities our attachments. Basically, how we live in the world and all those ways of being in the world that kind of make us who we are and feel how we are. That when we talk about fossil fuel and energy and climate change, and food and all of these various practices we’re basically going right into real existential territory.

So, I think what I observe is that for those working to push for an advance an accelerated transition away from fossil fuels, which we need to do, we can overlook that or we can almost get impatient or frustrated with you know, come on, let’s go on with it, we not only do we need to do this everything that you care about is at stake here. And if we do this, we will have an even more positive and beneficial future and way of life for all of us. So, there's that difficulty to you know when we see that as possible to actually slowdown and pause and really kind of attune to what might this bring up for people whether or not it's rational. Whether or not it's even reality-based. How do we really pay attention to those fears and anxieties?

Because when we don't that's where exactly what leads to inaction to resistance to all the things that we’re actively working against when we don't actually acknowledge and address those anxieties and those fears.

Greg Dalton: When we’re talking with other people about difficult issues, whether it's climate change it could be abortion other things. You talk about four roles, educators, cheerleaders, righters, and guiding. Righters with R-I-G-H-T-E-R-S. So, tell us about those roles and how they frame the way people talk to each other about difficult issues.

Renée Lertzman: So, when we care very deeply about issues and we’re actually trying to help and be helpful on behalf of the planet and humans, we tend to fall into these modes of being that are very common. And what I've observed over working with organizations for many years now are these very kind of predictable modes very understandable modes. It might look like being an educator where we really focus on educating and we really believe deep down in our heart of hearts that if people really understand the issues that, you know, really get it that they can't help but want to do something to change the situation. So that's the –

Greg Dalton: If you knew as much as I do about this then you’d think my way.

Renée Lertzman: Yes, because that's often what our own story was, right? That we had a wakeup moment we had the light went off and so we wanted therefore have others to have that same kind of experience and so we lean into being an educator. The other mode that's very common is a cheerleader. A cheerleader is, you know, feeling like we have to keep things really positive really upbeat various solutions focused and sexy and all of that which is sort of like the other end of the spectrum which is we don't want people to feel overwhelmed or you know, bummed out the whole doom and gloom thing. So, we’re gonna keep things really upbeat. So that's a cheerleader mode, which is can be pretty exhausting for a lot of us.

The righter mode, R-I-G-H-T, that language comes out a motivational interviewing and that refers to righting. So that's the righteous, the moralizing, the ethical, like you know the finger-pointing where this is the right thing to do. And if we don't do this now, we’re all gonna, you know, be in really big trouble and that's a very strong stance that makes a lot of sense as well.

So, all of those modes the educating the cheerleading and the righting, they all make complete sense. But they're not actually very effective on their own at truly engaging people, especially people who are not already dialed in. Which let's face it right now at this moment in time, we have got to level it up. We've got to be able to develop more sophistication and more skill like engaging with much, much broader groups and communities than we have been, right. So, it's on all of us to do that. And the paradox is that educating, righting and cheerleading don't really get us there.

But what I found does get us there is when we bring those together in a new way and we actually show up as guides. A good guide actually knows a lot. You don't want a guide that doesn't know a lot about where you're going and what you’re doing. A guide has a very deep expertise and a guide knows what to do or not to do. Don't fall off that don't go off that trail you're gonna you know fall off the cliff. So, a guide can be very directive, but at the same time if you think about the experience of being with a guide, guides listen and they work with you and they partner with you and they give you the sense that we’re in this together and let's go you know let's do this. And it’s a nuance but it's a very powerful very effective shift that I see our community starting to evolve more into and I think needs to be growing into right now right at this moment, more than ever.

Greg Dalton: What do people who care about climate need to do? There's some hope for bipartisan climate progress, but a lot of people on the left are upset at the Republican Party for blocking climate progress and shaming on people for supporting Donald Trump. If people who care about climate want to come together and have something bipartisan meaningful in 2021 what should they do? How should they approach that?

Renée Lertzman: Well, I think it's essential that we begin or continue the work of true conversation. And, you know, we talk a lot about climate conversations we've been talking about it for years. I don't think we actually really understand what that means. And what it means is really centering our climate crisis in the context of compassion and recognizing that these are profound and existential issues that that are scary and overwhelming for a lot of us. And that we need to be having honest and open conversations. What we’re needing right now is to lean in to convening and forging new ways of interacting and connecting right now more than ever.

It's truly about a moment of care. It's shouldn't just be moment but right now my hope is that we enter into a true kind of moment where we bring care to every aspect of what we do. And, you know, this relates to the need to push ourselves, to stretch ourselves, to have uncomfortable conversations with people that we are not used to talking to and to, you know, to look at how can we resource ourselves and support ourselves so that we are better able to do that. So, you know, again the frame is, how do I develop myself and how can I help develop and support those around me to grow and to know that this is the long haul, right. This is really the long haul.

I know that we’re all exhausted. We are all feeling absolutely maxed out that many of us are feeling stretched in ways we never could've possibly imagined. And we've got a real cognitive load going on where there are so many kinds of inputs and pressures and stressors and all of that. So that's all a given, right, that that’s where we are. And I prefer to see this as a gateway. It's a gateway into a deeper, you know, it's a deeper way of doing our climate work and our politics and our educating and our, you know, innovating and all of that all of these activities that we’re needing to do right now. I think that we’ll find when we bring humility and we bring kindness and care and compassion into the mix of our work on the front lines of advancing change, keeping the pressure up, keeping it going, we’re gonna find that we’re gonna have so much more traction and we’re gonna be less exhausted.

---

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about moving through our feelings as we move past the election. That was Renée Lertzman, climate psychologist and founder of Project InsideOut. Coming up, Utne Reader founder Eric Utne confronts our collective mortality.

Eric Utne: Life is ephemeral. Change is the constant. And the big change is we may die at any moment. And, you know, I'm especially motivated by the thought that all of us may die. [:13]

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking about processing the feelings brought up by the 2020 elections: hope, anxiety and - depending on how closely the outcome matches your expectations - even grief.

Eric Utne’s new memoir is “Far Out Man: Tales of Life in the Counterculture.” The title is a play on his Norwegian surname, which translates loosely as “far out.” We spoke on the morning after the first Biden-Trump debate. Utne told me that, as a self-described magazine junkie, he started the Utne Reader in 1984 in order to shine a light on the best of the alternative press.

PROGRAM PART 3 - ERIC UTNE

Eric Utne: In the 70s, 80s and 90s I was able to track a lot of different kind of ideas and social movements and currents from my perch in Minneapolis, Minnesota by reading magazines and browsing newsstands. And that was the way we sort of surfed the web of ideas at the time. And I had a tendency to photocopy and send favorite articles to a few in my family or friends, and I knew damn well they weren’t gonna read them. So, I got the idea that I should publish a digest of the best of them and make them pay for it. So, I put together what I thought was gonna be a little newsletter. Initially, a 12-page newsletter then it grew in a couple issues to 16 pages.

And then I realized that people weren't, they were taking me up on my free copy offer, but they weren't actually paying for it once they got it. So this was in 1984. So, I had to suspend publication and retool it and I designed 128-page magazine and sent that to everybody who taken me up on the free copy offer. And this time people did pay for it and it just it grew like topsy to eventually 300,000 which was twice the size of Harper’s three times the size of The Nation and The New Republic and the National Review. And it had the most educated readers after the New York Review of Books more educated than the New Yorker, the Atlantic and Harper’s but they were 10 years younger and they were very active. They were truly activists.

So, my favorite thing at the magazine was to introduce the readers to each other in what we called the neighborhood salon movement. And we set up 500 salons all across North America there were 17 of them in San Francisco, 40 in the LA area 29 in New York. The Blue Man Group met in an Utne salon, marriages, businesses, cohousing projects, schools all got their start in the salons. So that was my favorite part of publishing the magazine was bringing these people together.

Greg Dalton: When you were younger how important was hope to your personal identity and work?

Eric Utne: Well, I was a hope junkie like many baby boomers. I was optimistic and thought that, I actually was -- I realized listening to Donald Trump and Joe Biden last night that I was probably raised in a Trump like setting. I thought that I couldn't have anything but hopeful thoughts or I would create my thoughts would create the reality. And I was afraid to have anything but hopeful and optimistic thoughts. And I realized how that plays out last night in watching the debate. It doesn't play out very well.

Greg Dalton: So, you were hopeful when you're young because you thought you were that’s the way you were supposed to be because if you had less than hopeful thoughts that they would somehow manifest themselves. So, you like you pushed anything else away?

Eric Utne: Yeah. And I think that's a fairly typical American certainly baby boomer worldview or kind of approach. But it took me, you know, a lifetime to get over it. I’m a recovering hope junkie now. And I like to say that I'm not hopeless, I'm hope free.

Greg Dalton: And you say you lost hope slowly over time. If there was one moment when it really died for you. Not long after Donald Trump election, you realized that if Hillary Clinton or even Bernie Sanders had been elected, we’d still be rushing headlong over a cliff.

Eric Utne: It was less a moment. I mean I don't want to -- I think Donald Trump is a symptom rather than the cause even though I do think he’s, you know, he’s a symptom of hope run amok. I mean, he was raised on Norman Vincent Peale and the power of positive thinking. But it's really it was reading Paul Kingsnorth and the Dark Mountain Journal and the Dark Mountain manifesto a few years before that. That kind of opened my eyes. Paul Kingsnorth was an activist and environmental editor for 20 years in the UK worked at The Ecologist and was very active in environmental protests and other work. And at some point, he realized after 50 years of environmental action of environmental movement, things are going in the wrong direction and his conclusion was it's not gonna turn around. And he said a piece in the New York Times in 2014. He said when people use the word hope with me I reach for my whiskey bottle.

And I got it and actually ended up going to Ireland to work on my book and went to meet him and his wife and two kids living in the back of the beyond in rural Ireland. And, you know, I was struck by how hope free he was. He wasn't despondent and despairing except possibly on a deep existential level, recognizing that we’re all mortal. But he was raising his kids and living his life with beauty and grace and it seemed that love was informing his behavior rather than hope. And I think that's a big difference.

And so, when I think about being hope free it’s not despondent and despairing. It's realizing that there's another choice. We have a choice, moment by moment to do and to act in the world to be a grandparent to my grandchildren. Not out of hope but out of love. Just shower them with love. And so I'm actually kind of lighter and freer and more activist than I've ever been, partly because I've finished eight years of writing this book and now I'm free of that.

Greg Dalton: That’s a certain freedom. So, it's counterintuitive, and perhaps a paradox to say that when you realize when you let go of hope most people would think that leads to despair, depression like so much of the climate conversation, is there hope can we turn it around. It’s just obsessed in this future what I hear you saying is what a meditative person would say is, we don't know the future, what we have is right now and it sounds trite and cliché. Live in the moment, right. But it's one thing to say it, another thing to do it. So, you're saying that you're liberating you don't see hope and it's okay?

Eric Utne: Yeah, I mean we’re all mortal. We’re all gonna die sometime. The bigger dilemma is that maybe the civilization is mortal, maybe it has a lifecycle. And maybe we’re winding down. I mean Margaret Wheatley writes a book called Who Do We Choose To Be? And she looks at the lifecycle of 22 civilizations, I think. And we’re very much in the kind of end times behavior this polarization that separation of the haves from the have-nots. The rampant exploitation of national resources. We’re exhibiting all those behaviors and she says that at some time in most of those civilizations a kind of warrior shows up a spiritual warrior who feels called to preserve those things that are worth preserving in the society and to help protect the people help them transition. And to help people find the others find their true community. And that's where I think we are right now is find the others and live a more -- well, you know, in this piece I talked about a kind of hyper local Green New Deal where we really need to turn our attention while being mindful of what's going on on the planet and on the national scale. But where we can really affect change is locally is family and friends and neighbors. That's where it can happen. And we’re so divorced from that so estranged.

I tell about meeting Margaret Mead actually a few times and interviewing her about tribalism and community. She said something to me that really struck me. She said 99.9% of the time that humans have lived on the planet we have lived in tribes. And then she defined that as groups of 12 to 36 people. And she said only during times of war or what we have now in modern urban Western cities does the nuclear family prevail because it's the most mobile unit that can ensure the survival of the species. But she said for the full flowering of the human spirit we need tribes, we need groups, we need community and we don't have it.

People are desperate to dive deeper than the either political debate or the chitchat that happens over the water cooler to something really deep and meaningful. And that's what your show is trying to do there’s not many opportunities for people to really dive deep.

Greg Dalton: And COVID seems to be bearing that as well. The isolation of COVID in some ways there’s more connection with COVID because we can just click on you and you and I, we’re talking over the Internet now from across the country. So, you said a little bit how COVID is a gift. How is COVID a gift?

Eric Utne: Well, it confronts us with our mortality and that's a good thing. I had a Tibetan friend, Tashi. And he was working in the laundry of the Children's Hospital schlepping soiled linens. And then someone realized that this guy is really different. He had a kind of presence that so they asked him to leave the laundry and to come up into the ward where people were terminal either because they were at risk of taking their own lives or because they had been declared terminal with cancer, especially. And I said, well, what did you do with them? And he said, well, I just sit and talk with them. What do you talk about? Well, life is very precious. And then I asked him, do you have a spiritual practice? He said, yeah, I think about death every day. And that really struck me at the time as kind of morbid, but now it’s kind of spiritual practice.

And I also I think COVID, I think the fires and global climate change and how it shows its face everywhere we turn. And the chaos in the streets and what's going on with the economy. I mean there are so many fronts in which changes so huge and extraordinary that we realize that life is ephemeral. Change is the constant. And the big change is we may die at any moment. And, you know, I'm especially motivated by the thought that all of us may die. I mean climate change is really it could get much worse very soon.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, so it seems to be hard because so much of this is like, oh give up. There’s an alternative which is and you talk about how the boomers lost their way. The alternative is just like indulge into immediate gratification. Well if the world is ending let's party.

Eric Utne: Yeah. And then with COVID that doesn't work so well. But there’s another path and that's Extinction Rebellion. And what they're doing in the UK right now, which I think is really exciting. And Zadie Smith, I don't know if you saw what she said a few days ago, but there's a group within Extinction Rebellion called Writers Rebel. And it’s writers like George Monbiot from the Guardian and Margaret Atwood and on and on, and Zadie Smith. And Zadie Smith spoke and she said that six years ago she talked about climate despair and how that was kind of almost a species shame that humans, it was a natural feeling that people would have because so much of life dies at the expense of our lifestyles and our energy consumption and our food choices and the rest of it.

She said -- they were protesting in front of the offices of the Global Warming Policy Foundation which states on its website, “While the foundation is open-minded on the contested science of global warming it is deeply concerned about the costs and other implications of many of the policies currently being advocated.” That's from that foundation. And so, Zadie Smith writes, let’s see here. “She realized that her previous beliefs that climate change denial was rooted in a genuine fear was naïve. Now we know better, she wrote. Now we know the outsized unruly emotions that surround the scientific fact of climate change. They’re fueled by something far more calculated and external than species shame.”

Basically, it's fueled by think tanks and right-wing lobbyists who are paid by the financial institutions and the oil companies. And Mark Rylance and a number of others are really stepping up and saying yeah this is a concerted effort to make us feel that we just have to change ourselves and things will get -- that's what it's gonna take to survive. We don't need to reach out to each other as you were talking about in community but also insist together that our government change its policies to be more not just environment friendly but to really make to recognize that this is an existential crisis and we need to face it now.

So that's the other part of giving up hope is realizing that we still have to act. We have to do whatever we can to make a difference in the way that we best know how to use our energy and talents.

---

Greg Dalton: You’ve been listening to a Climate One conversation about what’s next for the climate movement in the wake of the 2020 elections. We just heard from Eric Utne,

Founder and publisher of the Utne Reader and author of the new memoir, Far Out Man: Tales of Life in the Counterculture. My other guests today were Renée Lertzman, climate psychologist and founder of Project Inside Out, and David Roberts, Energy & Climate Change Writer for Vox.

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation.

Greg Dalton: Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Sara-Katherine Coxon is the strategy and content manager. Steve Fox is director of advancement. Anny Celsi edited the program. Our audio team is Mark Kirchner, Arnav Gupta, and Andrew Stelzer. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.