Another Look at Bridging the Great American Divide

Guests

John Curtis

Joan Blades

John Gable

Summary

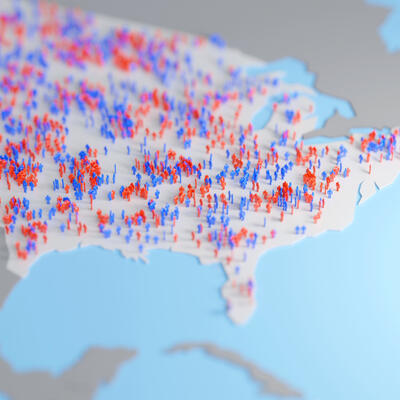

Most Americans support climate action, but you wouldn’t know it from Congress or the courts – or from most of the media. A recent study found that a majority of people significantly underestimated the extent to which their fellow Americans are concerned about climate disruption, as well as public support for policies to address it. That misperception can affect our ability to work collectively on climate action.

People on both the left and the right experience the same devastating floods, the same life-threatening heatwaves and catastrophic wildfires. Yet in our increasingly online and partisan world, we tend to isolate ourselves from information tha t disagrees with our worldview.

“We all are biased. We all live in bubbles. We cannot rely just on ourselves to be fair or balanced, or see the world evenly,” says John Gable, co-founder and CEO of AllSides.com, a website dedicated to fighting political polarization online by presenting the same issue covered by media outlets with different political leanings.

“Common ground is boring for press, it's not good click bait,” he says. Falling back onto polarizing viewpoints and echo chambers is often easier, especially via social media. But finding that common ground across partisan and other divides is essential to making progress. “We have to decide what's more important to us: being right about that issue or actually solving the problem.”

But we know it’s possible to find common ground on climate. Back in 2008, for example, John McCain and Barack Obama shared a similar stance on addressing climate change.

Mediator and attorney Joan Blades is a co-founder of MoveOn and LivingRoomConversations, an open source platform to encourage discussion across ideological, cultural and party lines. She recommends starting from a place of relationship-building as a way to find understanding with people who hold different views. “It's that relationship and starting to soften these boundaries that we’ve been creating between each other that's most important,” she says.

As an example, with one friend, “when we started becoming friends, climate wasn't on his list of concerns. And it got on his list of concerns not because I'm a brilliant presenter on climate but because he cares about me,” Blades says.

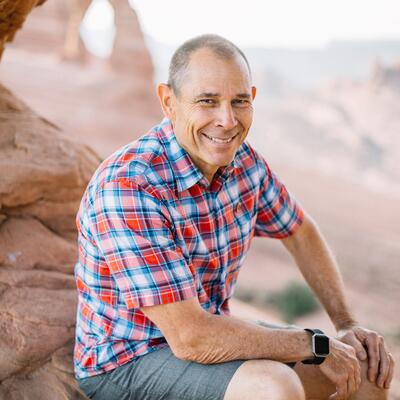

Republican Rep. John Curtis of Utah is chair of the Conservative Climate Caucus. He hosts dinners with friends and colleagues farther right than himself to talk about climate, and tries to start from a place of mutual connection.

“It's hard to come into my home and listen to me talk for an hour without them understanding why they should be engaged, why they should care, and that, by the way, they don't have to abandon their conservative values to be very good at this. And I make a pretty strong case for that.”

Curtis focuses on local issues when talking with his constituents, and says he’s found three easy topics for conservative Utahns to join the conversation.

“They care deeply about the Great Salt Lake and the shortage of water…regardless of the political affiliation. They care deeply about forest fires. They care deeply about the ski season. And these are not political issues.”

Episode Highlights

2:00 Rep. John Curtis on his home electrification

5:15 Connecting with Utahns over local climate impacts

8:00 Curtis on hosting far-right friends for climate conversations

13:30 Why Republicans oppose IRA when jobs and funding are going to their districts

17:00 Need for bipartisan legislation to make it lasting

18:00 New House Speaker Mike Johnson

23:30 John Gable on why common ground is a hard sell

27:00 Joan Blades on why we are not rational beings

35:20 Different camps use different language

40:00 Addresing our loneliness epidemic and divided ideologies simultaneously

44:00 American news has a trust problem

47:00 Getting around villainization of those we disagree with

Resources From This Episode (4)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: And I’m Greg Dalton. It’s that time of year when we gather together with friends and family to celebrate what we’re grateful for, to eat too much ...and navigate some difficult conversations.

Ariana Brocious: You wouldn’t always know it from Congress or the courts, but despite what many of us may think, most Americans support climate action. Regardless of our political leaning, we underestimate how much we ALL want a habitable planet.

Greg Dalton: Yeah that makes sense – people on both the left and the right experience the same devastating floods, the same life-threatening heatwaves and catastrophic wildfires. Yet we tend to live in social bubbles, information bubbles and see the problems and solutions through different lenses. Use different language.

Ariana Brocious: But there are some working to bridge this divide. Republican John Curtis represents Utah’s third district in the House. He’s chair of the Conservative Climate Caucus. We had him on the show earlier this year.

Greg Dalton: Right. I really enjoyed talking with John – (reflect more) and appreciate him joining us again.

Ariana Brocious: News peg of new house leadership.

Greg Dalton: Congressman, welcome back to climate one. I'm excited to talk to you again. Thanks for being a Republican, coming on a climate show.

John Curtis: Imagine that, right?

Greg Dalton: I watched your video on electrifying your home. Very cool. I saw the solar of course, and then the batteries, and then I saw the water. Part I was like, oh, this guy's really getting into it. He's doing energy and water. and I do climate conversations and your video was the first time I heard of a climate friendly dog door. So kudos for that. Why did you do all that work and spend all that money?

John Curtis: You know, there's a couple of reasons. One is, obviously, I do a lot in this space, and I thought it would be very hypocritical if I was building a home and didn't do it. I also wanted to learn. It was a very good learning opportunity for me. And so I, you know, in each of the things that we chose to do, we spent a lot of time researching alternatives. And then I would say number three, I'm absolutely convinced that these can be done in a way that is long term saves me money. I say long term because some of it, you know, there is some upfront cost with it, but my wife and I plan on being in that home the rest of our lives. So it's somewhere between one year and 50 years. I'm going to be living in that home and I want to save money. I'm very thrifty. I wanted to save money.

Greg Dalton: And you mentioned tax credits in the IRA for home electrification. Did you take advantage of those and how big a deal were they for you?

John Curtis: Yeah, so I, I want to be clear because some people feel like, uh, you know, uh, a Republican that didn't vote for the IRA shouldn't take advantage of those tax opportunities. But, uh, with some modification, they were all there even before the IRA, uh, the solar credit and the geothermal credit. And by the way, I was making my decisions before the IRA came along, but those credits, I mean, they clearly influenced my buying decisions. To do the solar, particularly the geothermal, just would have been very hard to get to pencil without the help.

Greg Dalton: Right. I did home electrification, did an induction cooktop, took out the propane, many of the things you did. That's good. And I think that to really address climate, it takes more than some privileged white guys, you know, putting in cool things in their houses. Would you agree?

John Curtis: I would agree, but let me, let me just bring up this point. I feel like too often, many of us don't want to change our lifestyles when we point to Washington, D.C. And say, Why don't you fix this? And I don't think we should underestimate the millions of small things. When I was mayor of my city, we had a valley with half a million residents. And I used to say, Look, if each of you would cut one vehicle trip per week, that is a half a million vehicle trips per week. And, I totally understand what you're saying, but I don't think we should disincentive or, or, overlook the value of individuals saying, no, I'm in this too. And I'm not going to only look to my federal government to solve this.

Greg Dalton: Right. That's, that's fair. Personal change is hard. It's easy to say someone else should change or, or do something. I saw that you met with some Olympians about reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Utah's in the running to host the 2030 Winter Olympics. Many of those events would happen at ski resorts in your district. What do you see as your role in that effort from a climate standpoint?

John Curtis: First of all, let me say, use this opportunity to point out in a very red state, Utah, we’re a very conservative state. We do a lot of oil and gas and coal that, one of the ways that we can get people turned on to this conversation is to show them how it impacts them directly. So in Utah, when you talk about the ski industry, people, they all of a sudden sit up and listen and say, okay, I'm listening, right? And so it's easier for me to point out the shortness of the ski season, that is starting later and ending sooner than it is something you know 10 000 miles away or 2 000 miles away And so I think this is a really good opportunity to say look local situations sometimes are what it's going to take to get people engaged. And for me, two things. Well, really, three things have been very important: pointing out what it's doing to the ski industry in Utah, pointing out the wildfires that we're having and the drought. And these are three easy place for very conservative Utahns to jump into this conversation. And to care. And let me tell you, they care deeply about the Great Salt Lake and the shortage of water at Utahns, regardless of the political affiliation. They care deeply about forest fires. They care deeply about the ski season. And these are not political issues. And so for me, having these things in my state has been a good opportunity to get people engaged who might not otherwise engage in this conversation.

Greg Dalton: Sure makes sense, making it a local issue. It's often seen as far away in time and space. Many people expected you to run for the Senate seat vacated by the retiring Mitt Romney. Why did you decide to stay in the House and not try to go for the Senate?

John Curtis: So this is a very complicated question, and all I'm going to say is let's just say it's not over. How about that?

Greg Dalton: Ah, okay, Alrighty, well, must be there's some change in polling or something there.

John Curtis: It's not a change in polling. The initial polling was incredibly positive. I think it's fair to say that since I announced that I wasn't running, there's been a drumbeat that is loud and consistent, asking me to reconsider. Including my wife and my children and many people close to me, and that drumbeat is getting louder and actually, quite frankly, a little bit more organized. And so, all of those things are consistent and loud enough for me to do a little bit of re-evaluation.

Greg Dalton: Interesting. So, as a former Democrat, you think that you're looking at a statewide run in Utah. Will you keep climate as part of your views if you try to go for that bigger seat?

John Curtis: Well, for good or bad, I've been associated in Utah with climate, and, you might enjoy this, tomorrow night at my home. I'll be back in Utah. I have invited 50 to 60 of the furthest right people I can find, and our topic will be climate. And it'll be about the fourth or fifth or maybe even sixth dinner that I've done with my very good far right friends because it's hard to come into my home and listen to me talk for an hour without them understanding why they should be engaged, why they should care, and that, by the way, they don't have to abandon their conservative values to be very good at this. And I make a pretty strong case for that.

Greg Dalton: Well, that's interesting is elsewhere in this episode we have a former aide for Mitch McConnell talking with the co founder of MoveOn.org, the progressive organization and it's just about that how getting people from different sides or different parts of a spectrum that you're not doing left and right. I understand. Are you going to change your language when you speak to your far right friends about climate? How do you get different people together around climate and talk about it without them shutting down right away?

John Curtis: So it's a great question and I think we do this on a number of issues and not just climate. I think you could point to immigration and other issues where we just quickly bring up these words or these terms that are divisive that spread us apart. And at the end of the day, there's actually very little that separates us on climate as Republicans and Democrats. And there's far more that we agree on. And Republicans do want to leave this earth better than we found it. We have ideas on reducing emissions and, I think a lot of Republicans make the assumption that to be good on climate, they have to embrace the green new deal. No, they have to bring their ideas to the table. To be good on climate if that does that make sense and and let's debate those ideas and and let's let's agree that less pollution is better than more pollution. And so, so what are those ideas that reduce emissions? And I don't talk to people a lot about the science, but I do talk to them a lot about What I consider to be a innate born inside all of us desire to leave this earth better than we found it.

And how do we express that? And I also talk a lot about the fact that the myth is that we need to give up energy independence. The myth is that we need to give up low prices. The myth is that we have to give up affordability to reduce emissions. And I think that's turned a lot of Republicans off that myth. And so we talk about the fact that like, let me show you how we do this without sacrificing energy independence. Let me show you how we do this without sacrificing affordability, reliability. And when we redistrict, I was given oil and gas in my new part of my district, and I went out to visit with them and I said, Hey, they, they said to me. I don't think this is going to work. You're the climate guy. Have you not noticed we're oil and gas? And I explained to them my philosophy of how they can actually be part of the solution. And nobody had told them that before. They've always been told they're the problem. And they like being engaged. And they like being challenged. And they like knowing what, under terms and conditions, they can actually be part of the solution. And my highest percentage of re elect came from the oil and gas part of my district.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I think it's actually called Carbon County. I've been out there. So you didn't mention faith. Of course, many Mormons in Utah, you yourself are LDS, there's been some moves lately to get, you know, something of an environmental creation care as part of the faith. How is that going to be part of the conversation when you bring these far right friends?

John Curtis: Yeah, you're right. By the way, the official name of the church is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints. People know us by Mormons, by LDS, , but officially that is our name. And part of the doctrine is stewardship of this earth. And I don't think we talk about that enough. And I think that's one of the ways I do connect with people. I mentioned, I think we're, we're born with this innate desire. I think that, in my opinion, that comes from God to leave this earth that he created better than we found it. And it's a big part of my conversation, and it's a big part of the way I connect with Utahns, and not just Utahns, but really people all over the country, I think, share that with us.

Greg Dalton: Does that include science? I know that there's some very good climate scientists in Utah, BYU and University of Utah. Does the science come into that?

John Curtis: Yeah, but you know, what's interesting is I find that science is very convenient for people. I like to point out sometimes my colleagues on the left. Like to pick what science they're going to use. The reality of it is, and I don't care if it's the science of COVID or it's the science of climate or the science of whatever it is, that if we're not careful, science is not a very good motivator. And I would show, you know, to my friends on the left, I'd say, you know, how's it working for you? Trying to convince Republicans with science, that they should be engaged. It hasn't worked. And so I think I can show you what does work. And I don't think we should have that litmus test out there that if you're going to engage on a climate discussion. You have to agree with me on the science. No. Can we just have the litmus test that you want to leave the earth better than we found it? And that's a very different way to engage people. People have different political philosophies and just take that temperature down, right? Of, look, do you want to prove yourself right on science? Or do you want to get Republicans engaged to talk climate? Well, I think we want to get Republicans engaged, right?

Greg Dalton: That's totally fair. It's complicated. You mentioned the Inflation Reduction Act earlier, which you voted against. I think you said because Republican ideas were not included. It passed on a straight party line vote. Political reported earlier this year that 198 billion is going into Republican districts because of the IRA. Nancy Mace praised the Volvo plant in Ridgeville, South Carolina for making all EVs by 2030. No gas powered cars. She voted against it. And some people are trying to claw back that law. Help me understand why your colleagues are trashing the law that's sending money and jobs into their districts.

John Curtis: I think this is really important, and if Democrats want to engage us, they need to understand this point that I'm going to make. So imagine being a House Republican. Imagine no ability to even offer an amendment on the IRA. Imagine being asked to spend $1.5 trillion at a time when inflation is rampant and the debt is soaring and given no input on the bill. In truth, there are many provisions in the IRA that actually started out as Republican ideas. And I'd point to nuclear and carbon sequestration and direct air capture –

Greg Dalton: Hydrogen.

John Curtis: Hydrogen. Yes, there's a lot that in standalone bills, Republicans would have supported. So people shouldn't be surprised that Republicans pushed back in the House on $1.5 trillion dollars of spending, when in reality, three, four, five hundred billion of that was for climate initiatives, that we couldn't even offer an amendment. And I'll just give you a really good example. I want to deal with methanes in cities and in city landfills. What a perfect place to have dealt with that. I couldn't even offer an amendment right on that. So when people say, well, you didn't vote for the IRA, that doesn't mean there aren't individual provisions that we don't support. That doesn't mean that projects coming in my district. I have to pretend I don't like because they were funded by the IRA. Of course, I'm going to like some of these projects coming into my district.

Greg Dalton: Are you going to be part of trying to roll back the EV tax credits or other things that seem to be a big part of the Republican plan for ‘25?

John Curtis: So how about this? Let me rephrase that question and see if even my democratic colleagues would join me in this. We have limited number of dollars to spend on reducing emissions. Let's make sure that we're spending those dollars on those things that reduce the most emissions most effectively. So yes. When we waste money on provisions that I don't think lead us to the best outcome. I think it's my responsibility to push back. I think it's democratic responsibilities to push back. And if we're honest in the IRA was a lot of shoot ready aim. Here's my pet project. I want it in the, let's fund it in the IRA, but nobody asked the question, how much carbon does it reduce per ton? What are we spending per ton to reduce carbon? And why aren't we doubling down on something over here that reduces more carbon per ton instead of spending money on this project over here? And I think Republicans have a right and actually a responsibility. This is why it's important that we're at the climate table.

We do need to ask tough questions and nobody should be afraid of the answers, right? Like there's no reason that we shouldn't have a debate about which projects should be have more money and which projects should have less money. And the IRA is not perfect. I think even my Democratic colleagues would tell you that. Remember, this bill was put together almost the middle of the night and and rushed through. And so–

Greg Dalton: Why weren't you able to, to, excuse me, why weren't you able to offer an amendment?

John Curtis: So, because we didn't control the House at the time, the way the package came and the way that we had the House rules, Republicans were just totally tick tock, the game is locked, and by the way, that was my Democratic colleagues in the House as well, it's just the way the package came to the House, it was the way that Nancy Pelosi set up for the rules on that, and the reality of it is, if you look at any legislation that comes through as one sided without input from the other, it's going to be pushed back on. And I'll go back to Republicans tax reform of 2017. No wonder my colleagues, they would say the same thing, right? They didn't have a chance to influence that legislation. Of course.

Greg Dalton: Your Democratic friends would –

John Curtis: Yes, sure. Of course, they're going to push back on that. If you go back to the bipartisan infrastructure act, where in the Senate, Democrats were given that chance.

We weren't given that chance in the House, and it became bipartisan. And so in the best of worlds, yeah. We pass bipartisan legislation because it's lasting, right? Because you don't have people taking shots at it later on. This is why all of my Democratic colleagues should cheer Republicans coming to the table to talk climate, because if they're going to do it without us, it's, it's going to be attacked, right?

But. To the extent that we can find agreement and find things that, and, and I, by the way, in history, I can show you, uh, you know, in, in, in the year 2000, we passed one of the most transformative climate bills that got totally overlooked it reduced hydrofluorobic carbons in the United States by 85%. That was bipartisan, right?

And that's stuck and nobody fought right afterwards.

Greg Dalton: Policy durability is a big thing. And that's, that's fair. Now your party, the Republican Party, does control the House. Have you had a chance to sit down with Speaker Mike Johnson and talk about climate and energy?

John Curtis: I'm smiling because we all know Mike's just a tad bit busy, but I will tell you this. He does acknowledge my work and that it's important for Republicans. And he's got a number of things he's dealing with that doesn't put us on the top of his calendar, but we have a little marker in there for him in a week or two or three, when he's got a window for me to be able to sit down with him and have this discussion.

Greg Dalton: And you're on the Energy and Commerce Committee, where most of the important legislation in this area happens. What would you like to see, what would you advocate for when you do get that sit down with the Speaker? And how will you include Democrats?

John Curtis: Yeah, so clearly the issue that's screaming, screaming at all of us, Republicans and Democrats, is permitting reform, and this should be a bipartisan issue, and my good friend from San Diego, Scott Peters, is very active on this, he and I are sitting down and talking about a permitting bill that he has out there that I like a lot of things about I think this can be bipartisan.

I think it's a great place for the speaker to jump right in and be supportive early on. And look, I don't care what your energy goals are. I don't care what your climate goals are. We're not going to be able to accomplish them without permitting reform. And both sides agree on that issue.

Greg Dalton: Well, John Curtis, thanks for coming on Climate One and, whether you stay in the House or in the Senate, come back and talk with us again.

John Curtis: Yeah, you bet. Thanks. Bye.

Ariana Brocious: If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods.

Coming up, why it can be hard to put aside differences and meet in the middle:

John Gable: Common ground is boring for press. it’s not good click bait. And actually, if you’re trying to raise money telling your contributors to the other side is evil and they’re terrible and awful… that's the easier way to raise money.

Ariana Brocious: Building buzz on common ground, that’s up next when Climate One continues.

This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: And I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And today we’re talking about bridging divides across political and cultural boundaries. We’re revisiting a conversation Greg had a few months ago with two people working to develop trust and find common ground to rebuild respectful civil discourse.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, because this is a hard thing to do. We naturally censor ourselves and avoid conflict so we don’t usually approach people who disagree with us.

John Gable is co-founder and CEO of AllSides.com–a website dedicated to fighting political polarization online by presenting the same issue covered by media outlets on the left, right and center.

Ariana Brocious: Mediator and attorney Joan Blades is a co-founder of MoveOn.org and LivingRoomConversations.org, where she invites people to bring a friend from a different viewpoint to discuss difficult topics like guns, mental health, and abortion.

Greg Dalton: John is a Republican. Joan is a Democrat. And I asked them each to reflect on how it’s become more difficult to have a good conversation about climate across the political spectrum.

Ariana Brocious: This interview was recorded live in front of an audience at the Commonwealth Club World Affairs.

Joan Blades: Well, politically the story of climate became one of the polarization points, which is kind of a tragedy. When in fact what I've seen over the last 10 years is the opportunities have totally changed. The cost of clean energy is less than the cost of oil, you know, that we can do clean energy so much more effectively is good for the local community good for the global community. And at this point, I think our division is causing us to not see how much we agree. There are huge opportunities and we are just not grabbing them because we’re so caught in this fight.

Greg Dalton: And John, this is painful for you because you think that there’s more agreement on climate than a lot of other things.

John Gable: So much more agreement on climate than most issues. A large majority of Republicans do believe in climate change do believe it's impact that's man-made do believe it's impacting our lives. Huge majority agree with some of the specific solutions like planning a trillion trees or actually using tax credits and other types of financial measures to encourage better behavior. There is a lot of agreement there and I think that's actually what we need to focus. I mean the political class who get elected by saying we’re better than all those other guys do not emphasize common ground. Common ground is boring for press, it's not good click bait. And actually, if you’re trying to raise money as an environmental group saying hey, we agree with the other side isn't necessarily the best way to raise money telling your contributors to the other side is evil and they’re terrible and awful. That's the easier way to raise money. So, there's a lot of opportunities here to actually work together and focus on the planet. I think all of us who really believe in this issue or any issue, if you will. We have to decide what's more important to us being right about that issue or actually solving the problem. So, if you hear me or somebody, you’re talking with saying hey, let's plant a trillion trees. Let's do financial incentives to have cleaner air. And I also say I don't think the climate is as big of an issue as you do. I think there are other issues that are more important today. So, if you stop and listen to that and think about how you might how we might respond to that person. If your tendency is to respond by saying oh the climate is really bad you're not paying attention to these things and that thing about the UN, saying that some of these scenarios aren’t likely to happen la, la, la, la. That’s one approach. The other approach is do you want to plan a trillion trees do you want to do financial incentives? Let me help you do that, let me introduce you to groups that want to do that. I will help you do that. The first response of saying what they’re wrong about is really about me or us being right. And my gosh we love being right all of us do we’re human beings we like being right. But does that really save the planet? If it's more important to you to solve the problem to address climate change, I recommend the other approach. Finding the common ground seeing where you agree and working together to make it real.

Greg Dalton: And a variation of that that I've heard is you want to be right or you want to be in relationship. And many people like that's like oh the relationship, right. So, Joan how does that when you're talking with people who have different views than you, you know, is there a little voice in you that wants to like spring facts or counter them or do you think, oh this is my friend, I'm going to be quiet and listen and bite my lip.

Joan Blades: Well, I'm not biting my lip these days. I mean what's been really great about this is making friends like John who I am curious why are saying things. John’s brilliant. John is someone I really trust at a deep level. And when we disagree it causes me to look at what I'm thinking. What I believe and where are the holes and why do we see things differently. This stuff is confusing. I mean it’s not that it makes life simpler, it's really easy when you got black and white, but we don't. And there's actually a lot of colors in this whole system too.

Greg Dalton: And you say that there’s, you know, research shows that people make gut judgments about people and our brains follow. So, what is that mean and contrary to often people say it’s not rational we got to be rational we got to be optimal.

Joan Blades: Yeah, people keep on thinking we’re rational beings. And it's nice fiction but over 90% of the time if you look at the science over 90% of the time we’re doing it by gut and then our reason follows. We rationalize why we made the right decision and that's human. So, you know, with my dear friend in Utah when we started becoming friends climate wasn't on his list of concerns. And it got on his list of concerns not because I'm a brilliant presenter on climate but because he cares about me.

Greg Dalton: Wow, he cares about the climate because he cares about you and you care about climate.

Joan Blades: Yes, and another friend of his, he has two people that he feels close to and we really care. And I care about him being concerned about being put in a position of being isolated and othered, you know, we care about the people we love and what they care about and that's good. So, whereas talking about climate change is really important, talking and having relationships across differences is critical also.

Greg Dalton: And it just seems, John, that so many conversations with people care about something they try to persuade over and one conversation over one beer or one meal. And so, how do you approach, is persuasion a persuasive or other way to connect with people?

John Gable: Joan has completely convinced me and brought me on board with the relationships-first piece. And when she and I first met, friends of us introduced us and we were at a walking around on a walk in Reston, Virginia on some parking lot. And I always say that if Joan Blades asks you to go on a walk, go on that walk because it was transformative for me at least. And what we found that we are both --

Greg Dalton: But did you trust her? She's this founder of this liberal MoveOn.org thing. Did you trust her?

John Gable: I never lived in a place where most people agree with me, so it doesn't bother me. Yeah, I’m a Republican in San Francisco who worked for Mitch McConnell so I’m really popular here. So, that's not unusual for me. And I'm actually I love discovering people I love finding that kind of brightness in them it’s just something I've learned, being from Kentucky and also being in both poor areas and then very wealthy affluent areas and going back and forth to like Bar Harbor, Maine, and coal mining Kentucky I learned at an early age how people can other, others, whether it's people without wealth othering those people fortunate or vice versa. And you begin to get a good sense of real character and not being caught up in the kind of covering of the book or the stereotypes. And so, it was very obvious to me what anybody who meets Joan it's not hard at all to recognize the sincerity and intelligence and just solid person she is. And we discovered that we are working on the same thing. I came from the technology side. 25 years ago, I worked at Netscape team lead for Netscape Navigator or the product managers. And 25 years ago, I gave a speech saying how I thought the Internet might actually train us to discriminate against each other in new ways. How I thought it might actually, as it evolved, divide us. And that was concerning because those of us who work in technology, those of us stayed up obscene hours, we wanted to create this thing and made it possible for us to all have better information to make better decisions.

Greg Dalton: It was gonna democratize information.

John Gable: And you can make better decisions on everything in life. And we would know people as individuals around the world because we connect with them on things like Zoom today and really get to know them. That was the dream of those of us working crazy. And in a lot of ways the Internet has done that. But when there's a lot of money or a lot of politics or a lot of power involved it's doing the exact opposite. And so, when we started AllSides, AllSides.com 10 years ago started creating technologies what I was describing was the Internet's broken. It's not doing what it was intended to do, and that's both scary but also kind of good news because that's technology we can change that. The business models around it we can change those. But whether they speak to our better angels inside of ourselves or whether they pull out the worst of us. That's what we have to develop and focus upon.

Greg Dalton: And I think it's fascinating that all sides actually uses humans in that. It’s a site that sort of compares side-by-side the headlines and narratives on the left the center and the right and they’re labeled LL, C, RR. And I thought oh, there must be some algorithm that’s doing that. But you got humans which I find fabulously reassuring.

John Gable: And I am a technologist, but I do think people get carried away with AI or algorithms. Because all algorithms mean, is it somebody you don't know behind a closed door deciding what was important and then they wrote the computer just decide that. So, they are biased. They are biased by whoever wrote them. And we were very interested in coming up with the system that was not in danger by our own biases. In all sides we have people in the left and right and everything in between. We joked we have never had food fights and occasionally some of our arguments get a little bit heated. But we consciously have people across the board but that's not good enough. And journalists who really work hard to present news fairly they’re just doing it inside themselves. We all are biased. We all live in bubbles. We cannot rely just on ourselves to be fair or balanced, or see the world evenly. So, we created a system based on American people all across the nation to be able take a look at different things and we reflect what they would see. And we use that not so much to say, oh, you’re news media you’re a left or you’re a right. We use it mainly as a way to enable all of us to quickly see different perspectives on the same issue on the same news. Because the idea of technology for my point of view is to enable human beings to do what we do best think for ourselves decide for ourselves connect with other people. Technology is to serve that not replace that.

Ariana Brocious: You're listening to a conversation about what it takes to cross political divides and make progress on climate. When we come back, why we should make a habit of talking to people who disagree with us:

Joan Blades: When we have a conversation that's about a polarized topic you don't want to get a bunch of people that agree in the room because you come away feeling more extreme.

Ariana Brocious: How to become less extreme. That’s up next.

This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: And I’m Greg Dalton. For today's show, we're channeling a Thanksgiving meal -- inviting family members of all political colors to the table for some comforting food and conversation. We’re talking about better ways to communicate and find mutual understanding, especially across ideological divides.

Ariana Brocious: Let’s get back to your conversation with two people with opposite political leanings: Joan Blades of Living Room Conversations dot org and John Gable of All Sides dot com. You spoke in front of a live audience at the Commonwealth Club World Affairs in San Francisco.

Greg Dalton: So, Joan, when you're talking to your conservative friends in Berkeley where you live people talk about planet and earth and others talk about markets and jobs. So, how do you deal are you careful about the language you use?

Joan Blades: Absolutely. When I started Living Room Conversations it was to be about climate and energy. We rapidly learned we should just have an energy conversation because people that don't believe in climate aren’t coming to a climate energy conversation.

Greg Dalton: But energy you can get them in.

Joan Blades: Yeah, and the people that care about climate they’ll be here about that in the process. Over time I've come to believe that, have a conversation about anything. It's that relationship and starting to soften these boundaries that we’ve been creating between each other that's most important. I mean talking about the technology there is a thing about algorithms that’s really problematic because with Facebook and all these different platforms. If it causes anger, fear, anxiety it's more likely to get shared and the algorithm is to get maximum profit which is maximum sharing. So, we have to become intentional about what we are taking in that's why I love All Sides because that’s a way of saying, actually, I want to see the full picture.

Greg Dalton: John, do you think that some of your liberal friends are too shrill and over worried about climate?

John Gable: I think everybody is in one issue or the other there's always people who are too shrill or too worried on any issue. It’s interesting, I don't really think about it that way. I do think that a lot of people in the right do think folks go too far --

Greg Dalton: Alarmist. Oh, it’s not as bad the climate, oh.

John Gable: And they lose little credibility when they kind of push some things. But I think that there is always a debate on any issue on different sides, on what's the solution there are always people who’d be a little bit more extreme. I think that's always going to happen particularly in an open society like ours we have different extremes arguing different pieces. I think the real question is what works, what do we do. And Joan mentioned that 3 1/2% of people 75% of Americans would prefer news that’s not slanted one way or the other or 78%, my apologies from Pew Research. And that's a big change from just two years before that where it was in the 60s. We have 3.5% of the people of America being engaged in some kind of idea for movement to succeed. If we only talk about voters that’s like five and a half million people or a little over 10 million people we’re just talking about adults. That's a very achievable number. We’re talking specifically about how to engage that number of people in ways that really solve problems. Because when you get the number of people engaged, culture changes, policy changes. And the fact that there are some people who may be more shrill or one way on the extremes on either side of the issue. I try not to be disrespectful about it, but to some extent they don't really matter. The people who matter are the ones who are trying to solve the problem who are truly listening to each other to solve the problem to avoid the pitfalls of either extreme. And so, if you really believe in the data you got to commit to the processes that work to lead to better solutions which includes open conversation with people who disagree with us who aren’t experts in the area in order to get the better solution decided and acted upon. And that's our opportunity.

Joan Blades: So, one of the thing that's exciting, you know, COVID cost us not to be here for a couple years, but we’ve got tens of millions of people that are really comfortable having conversations by Zoom now. We have a problem with local connection. We also have a problem with national trust in connection. It would be possible if people are ready to show up. We could do this at a massive level if people wanted to. Now, what makes this harder than what I did with folks years ago with Move On is you just sign a petition you wrote a sentence about why you wanted to censure and move on. This requires showing up with --

Greg Dalton: Relationships are hard they take a lot of time and like they’re kind of messy and like you get vulnerable.

Joan Blades: And we have a problem with loneliness in this country, isolation and belonging. So, it’s the answer as well as the hard thing.

John Gable: It’s both a hard thing and what everybody in the nation in the world who are feeling alone are craving. We are wired to be tribal. We are wired to go against each other. We’re also wired and needing connection. And connection across differences means that I can show you who I really am, rather than what I'm supposed to be according to TikTok videos or whatever that has to be which really damages us psychologically. So yes, it takes more work but it is really as Joan points out, fun and much more fulfilling at a deeper level. We as a society need this even outside of climate change. We as a society need to learn how to connect and disagree in order to share who we really are and be more fulfilled as human beings and healthier.

Joan Blades: Last year a book was written called The Power Strangers just about all this data about how we’re better off when we talk to strangers. We have fears about that and we have to overcome them, but we’re happier we’re healthier it brings our day up. And so, this is actually creating a context where we shift the story so that more people that talk to strangers. But the beauty of the one form of Living Room Conversations was it his two friends each invite two friends and that personal invitation you get to meet a couple strangers you get to see a couple friends. And then you have a conversation that goes deeper than it otherwise would.

Greg Dalton: But, you know, John, in the political system however, I hear that we’re wired for this, we need this and the business and political incentives are all going toward the extremes for the clicks and the primary wins. So, what does that mean we have to change culture first?

John Gable: Well, you're seeing we’re seeing in a lot of hard data a real rebellion against that. So, Churchill's old quote was “America will always do the right thing, after it’s tried everything else.” And I think we tried everything else recently. And now we’re going, that's not working. And there is a shift: there's over 5000 organizations nationwide according to something that Princeton did that are focused on bridging divides. The demand for something other than the pundits yelling at each other is real. And the fact that news in America has the lowest level of trust in any nation top 45 nations in the world according to Pew, there is less trust in America for our news system than any other nation. And the more and more they go for that clickbait and just taking one agenda or the other or just emphasizing the differences and never dealing with problems, the more and more their credibility go down. That's the biggest problem in news media today is their lack of credibility or what I say the lack of trustworthiness.

Joan Blades: And I’d say it’s something even more than unhappy with the news. It's like it's causing people to turn it off because it makes them unhappy. It makes them anxious. It makes them fearful.

Greg Dalton: My wife can't stand watching, she's disgusted and I think I have another problem I take in too much of it. So, I've been trying to have a news diet lately because I realize it’s kind of toxic for me, like do I really need that one more article about whatever it is like is that… to have an information budget diet just like that’s enough.

Joan Blades: I read a whole book about how it’s bad for you to like really limit your news intake. So, yeah, what does that say?

Greg Dalton: Listen to more podcasts, that’s what I think.

Joan Blades: I think would -- yes, this is a positive solution.

Greg Dalton: And also, yeah, to have a little bit of variety because I think we get on this wheel of like inhaling information and somehow, I feel like the more I know, I don’t know, something, the better I am.

Joan Blades: So, the question is, as we try and know more so we can persuade our friends is have you actually persuaded someone that really disagrees with you? And that's really interesting things about the Living Room Conversations. When we have a conversation that's about a polarized topic you don't want to get a bunch of people that agree in the room because you come away feeling more extreme about that. You really want to be very intentional about differences in that room. And there also depending on the conversation you're having it can be age differences it can be cultural differences it can be political differences gender differences. It all depends.

Greg Dalton: And so, one thing you mentioned just brought up for me, you know, villainization. It’s so easy to villainize and raise money. So, let’s talk about villainization which is part of this polarization. Because there are some people in climate world who are villainizing oil companies and like say, oh, you talk to an oil company or you whatever, like you’re a suspect. John, what do you see?

John Gable: Well, that’s a tried-and-true American entertaining thing to do. I mean back early days we’ve always done that but there was a difference. Back then, when we had and I mean articles written by Ben Franklin or the Tories or Common Sense. They were really, really out there and villainizing --

Greg Dalton: Vicious.

John Gable: Vicious. I mean we’re kind of kind tamed to a lot of things that were written back there but there was a difference then. The difference is that the people reading those articles first of all, they knew that that was from Ben Franklin, The Tories. So, they already knew the point of view of that news. They did not believe that news is somehow accurate. They realized they were different opinions.

Greg Dalton: They were party papers.

John Gable: Yeah. And the time in America, the Walter Cronkite period, “this is the way it is” was really an aberration in history. Most of American history and most of history and all nations I'm aware of have always had kind of partisan different news organizations trying to persuade you. So, one thing is that they had a higher level of media literacy the people who are reading these pamphlets they understood that what they were reading wasn't necessarily true. So, a little bit of news and media literacy is important. The other thing that was different is that if Joan and I were back then in the 1770s. Sure, she was reading that rag from The Tories but she helps me get my plow on stock for my yard the other day and we knew each other as people. And that is a huge difference to know people out there. And so, knowing people outside of our world. When we only know our world, we’d come really confidently ignorant because we know 10% of the story, we hear it 8000 times so we are absolutely true. We’re more confident, less knowledgeable and we relationship with others that's just a bad combination all around.

Joan Blades: We have self-sorted in an amazingly effective way. And so, it's sorting in our, I mean I live in Berkeley I can speak about this with great confidence. Where we live, where we get our information, in so many ways and in those places where the mix is there’s a lot of discomfort in there a lot of flags people put up so that they can talk about the weather rather than about things that are really meaningful. And that's one reason this is such a good practice rather, it's not a one-time thing. It's a practice in faith communities and libraries communities are saying okay we need this because they have found that there are these gaps and people are isolated in all sorts of ways that are not good for us.

John Gable: And it’s important in schools too. School kids learn this more quickly, more easily. But it's actually a skill to learn how to listen to somebody you disagree with to really listen to understand. Not listen to answer not to listen to say how they’re wrong but to listen to understand that human being. And it's important, particularly in communities that may be more divided or have great crisis. It's great if you do it beforehand but when you hit that crisis, we need those skills. These are human skills, human beings learn this well. But we need the opportunity we need the tools online in our modern world where most the tools are doing the opposite. We need to provide people who want these tools to be able to hear each other and connect better and we’re building those to make that massively available to people.

Greg Dalton: Right. All the incentives and tools for transmitting not for receiving--

John Gable: We want to be right we want everybody to know that I'm right as opposed to tools for hearing and understanding others and connecting with others.

Greg Dalton: On Climate One today we’ve been discussing bridging the great American divide with Joan Blades, Cofounder of Living Room Conversations. And John Gable, Cofounder of AllSides.com. Thanks for joining us and thanks to John and Joan for joining us. Thank you all.

Greg Dalton: Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods.

Ariana Brocious: Talking about climate can be hard-- but it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Greg Dalton: Ariana Brocious is co-host, editor and producer. Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Austin Colón is producer and editor. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Wency Shaida is our development manager, Ben Testani is our communications manager. Our theme music was composed by George Young. Gloria Duffy and Philip Yun are co-CEOs of The Commonwealth Club World Affairs, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.