California’s Story: How Did It Get Here?

Guests

David Vogel

Huey Johnson

Jason Mark

Mark Arax

Diana Marcum

Faith Kearns

Summary

California has long been on the frontlines of environmental protection. These days, however, the state is also on the frontlines of a destabilized climate, careening between record drought and extreme rainfall, while its largest electric utility shuts off power to more than a million residents to avoid more damage from climate-amplified megafires.

“We’re gonna see havocs that have never been created before,” says Mark Arax, author of The Dreamt Land: Chasing Water and Dust Across California. “We’re going to be showing the way for the rest of the country, and so I think it's important to pay attention to what California is doing right and wrong.”

California has been showing the way since the mid-19th century, according to David Vogel, author of California Greenin’: How the Golden State Became an Environmental Leader.

“Beginning in the 1860s by protecting Yosemite, [California] has long been on almost every dimension the environmental leader in the United States,” says Vogel, who cites “auto emissions regulations, energy efficiency for appliances, energy efficient building codes, and coastal protections as initiatives that began in California and spread around the country.”

But can the state’s legacy of environmental leadership save it from the effects of recent weather whiplash? Diana Marcum won a Pulitzer Prize for her series of articles on California’s central valley farmers during the drought. Years of parched weather have taught her to appreciate the green times we do get.

“I think that’s one thing I took away from the drought,” Marcum recalls. “During it I kept thinking, I wish I would've paid more attention. I wish I could picture the snow. I wish I could picture the grass.”

Related Links:

California Greenin’ How the Golden State Became an Environmental Leader

The Dreamt Land: Chasing Water and Dust Across California

Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man

Scenes from California’s Dust Bowl (Diana Marcum, Los Angeles Times)

California Institute for Water Resources

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One, changing the conversation about energy, the economy, and the environment.

Greg Dalton: California has long been on the frontlines of environmental protection.

David Vogel: First unit of the United States to regulate automobile emissions... energy efficient building codes... energy efficiency for appliances.

Greg Dalton: These days the state is also on the frontlines of a destabilized climate.

Diana Marcum: Every night this cloud comes up and inside the cloud there's lightning that starts more fires. It is hellishly scary.

Greg Dalton: As it careens from drought to floods to fires, what will become of the California dream?

Max Arax: When you're that inherent nature that we have and then you add on climate change, we’re gonna see havocs that have never been created before and we’re going to be showing the way for the rest of the country. And so I think it's important to pay attention to what California is doing right and wrong.

Greg Dalton: Climate stories from California. Up next on Climate One.

---

Greg Dalton: Can California’s legacy of environmental leadership save it from climate disaster? Climate One conversations feature oil companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats, the exciting and the scary aspects of the climate challenge. I’m Greg Dalton.

Greg Dalton: Americans have been dreaming about California’s never-ending sunshine, fertile soil and rivers running with gold for over two hundred years. More recently, though, those dreams have been turning to nightmares.

[newsclips of fires, blackouts]

Greg Dalton: The state now experiences regular weather whiplash, amplified by climate change, careening between record drought and extreme rainfall. Yet extremes have always been part of life in California.

Diana Marcum: People came from all over the world and they didn't have a lot to get started. So that's exactly the places where some of our most beautiful and interesting cultures are.

Greg Dalton: Diana Marcum covers water, wildfire and drought for the Los Angeles Times. She and others will join us in the second half of today’s show to talk about the future of the California dream in the era of climate disruption. First we ask, how did the state get here?

David Vogel: California since ‘67 has had an exemption which has gone on now over 100 exemptions which, for the very first time in American history the Trump Administration is now trying to take away.

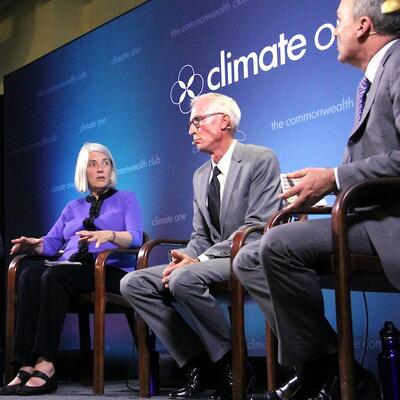

Greg Dalton: David Vogel is professor emeritus of business and politics at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of California Greenin’: How the Golden State Became an Environmental Leader. He joins us to talk about California’s climate legacy along with Huey Johnson, former California Secretary of Natural Resources and founder of The Trust for Public Land; and Jason Mark, editor of Sierra Magazine and author of the book Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man. We begin with David Vogel listing some of the environmental measures first adopted in California that have since radiated around the country.

David Vogel: Well, it’s the first unit of the United States to regulate automobile emissions, which began in California and then became national and spread to other states. Energy efficiency for appliances began in California, it became national. Energy efficient building codes began in California, it became national. The coastal initiative played a very important role in creating both national and local coastal management practices throughout the United States. So California from beginning in the 1860s by protecting Yosemite has long been on almost every dimension the environmental leader in the United States.

Greg Dalton: Great. And we’ll drill down into some of those topics. Huey Johnson, you founded The Trust for Public Land an organization that then grew across United States. One day you were walking by a park in San Francisco, there were some elderly Chinese people exercising and that was an inspiration. Tell us that story.

Huey Johnson: Well, I had an early morning meeting and I was walking by Washington Square with a city official to go to the meeting. And a lot of people were out there exercising. He stopped and he said, “That’s their living room.” And we kept going and I remember that it really made an impact on me. So I started a thing called The Trust for Public Land and it would have urban emphasis. And my first office I opened was in Oakland, the next one was in Newark in a minority community and we went around and had great success. We went to the banks and savings and loans companies and said, “You got all these properties you foreclosed on in these areas. If you give them to us we can give you a tax credit, otherwise you’ll never gonna get anything from them.” So we had a whole bunch of properties and established community gardens, schools, housing, a lot of things. The first property we bought when I started Trust for Public Land was out at Point Reyes. The next one was a huge canyon in L.A. And they’ve now acquired 3 million acres in urban sectors around the country.

Greg Dalton: The Black Panthers were also involved in these early efforts to bring parks. So tell us how you were dealing with national officials in the Nixon Administration and the Black Panthers at the same time.

Huey Johnson: Oh yeah, sure. The head of the Zen Center, Richard Baker was working closely with the Black Panthers and he was a good friend of mine. He said, “Why don’t you come and meet Huey Newton?” And I said, “All right.” And we go there and we go in an apartment. And there is Newton and a great big guy leaning against the wall with a pistol in his belt, protecting his boss. And Newton, we told him, I could train some people for you and they could acquire land. He said, “Let’s do it.” So they started coming to my office. And one day, there was a wall in two little conference rooms on each side. One side was Huey Newton and a bunch of other Black Panthers, on the other side was a group of vice presidents from the Bank of America all getting the same lecture. And they were really a fine outfit. It was sad that society came down so hard on them. They had visions and I thought great hope and they were nice people. I didn’t have any trouble with em.

Greg Dalton: Robert Hanna is the great-great-grandson of John Muir, cofounder of the Sierra Club. He now works as a staff member for the California State of Assemblies Republican Caucus. Let’s hear him talk about his grandfather and his legacy.

[Start playback]

Robert Hanna: I grew up learning about my great-great-grandfather in such a different way than most people. You know, my parents’ role was really to put us kids in the middle of the experience of our parks and open spaces. And as they always said that each one of us would form our own connection and bond with the outdoors. As a teenager I was going through a lot of stuff. I was really heavily, you know, hanging around with the wrong people. I was, you know, drugs, alcohol. And so I would often just take off, you know, going up to the Sierra where I knew none of that was gonna continue to tempt me. And, you know, I was able to break addiction. This would have been around, let’s see, 2011. And at that time, you know, there were 70 state parks on the closure list due to budget cuts. So I was able to roll up my sleeves and was part of the effort to work to protect the 70 state parks from closing. And from there, it just kind of started snowballing and soon I was able to bring together members of the legislature to create funding mechanisms for our parks. I was able to create legislation that was passed that connected veterans to our parks. And most recently was able to put together a legislation that passed that renamed the southern entrance going into Yosemite after the Buffalo soldiers. And currently I’m working on legislation to rename the highway going into Sequoia after Colonel Charles Young. My legacy that I want to pass down to my kids is action. Identify what makes you happy and dedicate yourself to doing that for the rest of your life.

[End playback]

Greg Dalton: That’s Robert Hanna, great-great-grandson of John Muir. And he referred to Colonel Charles Young, Buffalo soldier, civil rights leader and diplomat under President Teddy Roosevelt. Jason Mark, Huey Johnson talked about working with the Black Panthers and getting them involved in environmentalism. But overall the environmental groups have had a really difficult time engaging, you know, communities of color. Here we are four white men sitting up here talking about this, keenly aware of that. And so tell us about what the Sierra Club or other groups have done to try to reach out to communities of color because that iconic lone hiker, probably a man with a scraggly beard walking in the wilderness is a really strong image of what it means to be out in nature.

Jason Mark: Well, I think first of all it’s important to think about kind of riffing off of the thesis of David's book about things that have started here in California and then expanded. One I do think is the emerging people of color leadership within the environmental and the conservation movements. If you look at really the front-line communities and the grassroots leaders in places like Oakland and Richmond and Los Angeles, they’re people of color. Again, it’s sort of awkward to talk about four white guys on the stage but that is the truth. And I don’t wanna like guild that too much because the truth is that the environmental movement is still heavily white-led at the executive level and at the board level and still you don't have that diverse of national staff. That said, I do think the kind of emerging cutting edge of where the Sierra Club is and where other major conservation environmental groups are is ensuring that the 21st century environmental movement reflects the ethnic diversity of this country and doing that in number of ways. One is hacking that stereotype, right. So Sierra Club’s inspiring connections outdoors is working with communities nationwide to make those connections. You don't need to go to the very remote wilderness. Like yes, it's fantastic you go to Yosemite, go to Kings Canyon or Death Valley. But there's a lot of virtue in the nearby nature, right, in these urban parks and places like the Golden Gate National Recreation Area or one of our newer national monuments the San Gabriel Mountains in Los Angeles, right, where a plurality of people who recreate in the San Gabriel Mountains are Latino families. So I think it’s important to recognize that, yeah, we hold that stereotype, but when I find myself going out backpacking and certainly day hiking and certainly in our state parks, a lot of the folks in the front country are people of color and are coming from different cultural backgrounds and different ethnicities. And you see, especially here in California, you know, folks bringing in their own cultural traditions, especially let’s say Latino traditions of not going out like the solo white guy in the wilderness, but going out with your whole family having an asada, having a barbecue out there. That’s a lot of what I see at the state parks these days and I do think some of that is being broken down organically and some of it because the Sierra Group, the Sierra Club and other groups are making a real deliberate effort and intention there.

Greg Dalton: David Vogel, in writing the history of environmental leadership in California is it all white men, where were there people that, you know, people of color of other communities, you know, were they present? Were they part of it?

David Vogel: Well, women certainly had a very big presence. The initiative to protect the Bay came from four women who lived in the Berkeley hills who were appalled when they learned that the city of Berkeley planned to double its size by expanding into the Bay. And they started a major movement, an environmental movement to mobilize people throughout the Bay and eventually Governor Reagan signed legislation that created the Bay Area Development Authority. The first Coastal Development Authority in the United States and one of the first in the world. And that’s why the Bay has not continued to shrink and through its parks and its trails has become enormously successful and accessible to everyone who lives in the Bay Area. So this was an extremely Democratic impulse to basically make sure that the Bay would not be filled in and only available to property owners.

Huey Johnson: One quick story, in the East Bay and these four women who saved the Bay, I had just gotten here accepting a job as a western regional director of The Nature Conservancy, I got to my office, a little lady came in and she said, “Can I talk?” I said, “Yes.” She said, “I wanna save the Bay and we’re gonna save the shoreline over there.” And I said, “Oh, that’s fine.” The shoreline was owned by a railroad and there were rail cars parked along it. And I said, “Boy, she is -- no way that’s ever gonna happen.” Well, she persisted, it is now named after her.

David Vogel: And I think if you look at the coastal initiative that was a very Democratic impulse where, you know, most Californians live within 45 minutes of the coast, and by keeping the coast accessible which is unprecedented this means that all people of any ethnicity and of any income have access to what is a democratic part of California's heritage.

Greg Dalton: That coastal protection, which is very different on the West Coast than the East Coast, a lot of the East Coast is locked up, you can't, there's no public access. It's all privately owned. We sometimes take for granted this public access, and there’s lot of very high profile lawsuits lately over particular billionaires in Silicon Valley trying to keep the surfers off their land.

Huey Johnson: And it is important for all of us to realize that the next challenge is that we have to save the places that have been saved.

Greg Dalton: So where some people would say there's new land to be saved, Huey Johnson, you're saying people need to protect what has been saved because they can be unsaved.

Huey Johnson: That’s even more important. We pretty much save the places that need to be saved and there will be others. But places are being lost because there’s no defense for them. Right now the state of California up at Lake Tahoe is going to let the state park become a golf course. And Diane Feinstein is behind it and she has Goldman Sachs golf course division out in front and you really got to fight the bastards. The battle is never over.

---

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about how California became an environmental leader. Coming up, more about the state’s current climate crises, including the critical role of water.

Diana Marcum: There were people whose wells were going dry and there was no civic organization, you know, responsible, no government organization because it’s your own well. I don’t think anybody official understood how much suffering was out there.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about California’s climate legacy with David Vogel, author of California Greenin': How the Golden State Became an Environmental Leader; Huey Johnson, former California Secretary of Natural Resources; and Jason Mark, editor of Sierra Magazine. One of the keys to California’s environmental leadership was its sometimes tense love affair with the automobile. That relationship played out nowhere more vividly perhaps than in the city of Los Angeles, as David Vogel explains.

David Vogel: Well, L.A. began in the 1890s as a health resort because it had the best climate I’ve ever seen in the United States because it had no coal. And all these people would come to Los Angeles because it had beautiful air and you could be there during the summer without having to worry about -- because there was no air-conditioning it was pleasant. And then of course L.A. by the 1940s had the worst air pollution in the United States and no one could quite figure out why. And in 1949, there was a football game at Cal, Washington State playing the Cal Bears and during that day of the game people along the route of the cars began to experience the same kind of tearing and coughing that characterized smog alerts in Los Angeles. And that was the first inclination, the first idea that cars could be a major source of air pollution. And that started a trajectory that would, needed to be well researched et cetera, and by the early 60s California, understanding that cars uniquely were the major source of pollution in Los Angeles, that and California, enacted the country's first automobile emission standards.

Greg Dalton: At one point, the industry tried to argue that, well, it's not cars there’s something about L.A. that causes the pollution, right. It’s not our cars, it’s L.A.’s problem.

David Vogel: Yeah, and then they argued this is only a California problem, so that was okay. Then it became national and when New York began to establish its own automobile emission standards, the industry panicked and they said, “Okay we want federal standards.” And in 1967 they got Congress for the first time to enact federal standards. And then the question was, what happens to California standards? And the state was very worried that of course, the federal standards would be laxer than in California and California has a unique problem in that no other state has so much air pollution caused by cars. And it was a huge battle in Congress. It was very, very close because the industry wanted national standards. The federal government wanted national standards and a very famous story, Bobby Kennedy of New York went to the California Republican senators and said, “Look, you guys are gonna lose. You need to make this a state rights issue and get the southern racist Democrats to vote on California's side.” And that was successful and that is why California since ‘67 has had an exemption which has gone on now over 100 exemptions which, for the very first time in American history the Trump Administration is now trying to take away.

Greg Dalton: And so the Trump Administration which nominally supports state’s rights is trying to say California can't set more stringent air quality, actually fuel efficiency standards, which was one of the pillars of really the Paris Climate Accord because that really led the U.S. into Paris. So what's at stake there, is this gonna be drawn out in court for a long time because the Trump Administration is going -

David Vogel: Yeah, I mean it’s very consequential because curbing automobile emissions is very critical to California's climate change goals, greenhouse gas emission goals and to air quality. We’re driving more and more, and the only way to keep air quality and greenhouse emissions under control is to have better pollution controls, including electric cars. So this is a very serious issue. The industry's nightmare, of course, is that they relax federal standards which they can do and California keeps its exemption and thus we have a two-tier car market, California and 13 states one kind of cars, the rest another kind of federal standards. That's the nightmare for the industry. Because in 1977 the federal government gave states the right to choose California or federal standards and so many of them have chosen to adopt them. But the current fuel economy standards are pretty much national standards a compromise worked out with the Obama Administration. And so having dual standards would be a big deal.

Jason Mark: You know, one industry we didn’t mention, we got to mention this, is the organic agriculture industry. Which certainly I think is based here and born here out of California. You think about the new, the sort of good food movement sparked by Alice Waters and then folks like Michael Pollan. Michael Pollan’s got East Coast roots and the good food movement came out of other places but --

Greg Dalton: Earthbound Farms.

Jason Mark: Yeah, our food and agriculture industry and the landscape of what that looks like and the sort of cultural player if not a huge market player but the cultural player and the cultural force of the organic movement that started here in California and it spread to the whole country.

Greg Dalton: Yeah. So culture out of Hollywood, culture out of Silicon Valley, food for sure. Jason Mark, tell us there's been some suits lately where counties in California have tried to sue the oil companies saying you're at fault for selling oil that is causing our shores to erode and causing climate change.

Jason Mark: Yes, this is I think a probably right now among the sharpest point to the spear in terms of the kind of grassroots climate movement is now 13 different cities and counties across the U.S. And one state, Rhode Island, have now sued the major oil companies, coal and gas companies, you know big oil. And those suits started here in California. Now again that since spread, you’ve got lawsuits from three Colorado jurisdictions King County, Washington, City of Baltimore and state of Rhode Island. Now some of those suits have gotten tossed out, the suit from San Francisco and Oakland that was in federal court was tossed out, the New York City suit also in federal court was tossed out. But you still have all these state suits. And I think these towns and counties are very much committed to push these as far as they can. And while it is sort of an issue of numbers it is important for I think more cities to sign on that these suits, will present more of a threat to the major carbon polluters. You only need one to actually get the green light and go into discovery and then things are gonna get very uncomfortable for the oil and gas companies. And the oil and gas companies as then litigators are able to go in and request their internal documents which present the threat of them sort of repeating the path of big tobacco and being really publicly revealed.

Greg Dalton: But the oil industry response was very interesting. What they said to these counties was, “When you issued municipal bonds for your sewer plant or your roads, you also underestimated and covered up the climate risk to their investors.”

Jason Mark: Sure. A lot of people are hiding climate risk. The insurance industry is hiding climate risk, you know, every real estate agent in Miami Beach is hiding climate risk. I mean, these things are gonna come to a head when the horizon of the 30-year mortgage starts to run up against very serious flooding and sea level rise. And some of that property is here in California though I think the East Coast is probably in bigger trouble on that.

Greg Dalton: David Vogel, there are lot of examples in your book where business was pursuing self-interest or, you know, the railroads wanted forests to be preserved for one reason or another. What are some examples where business got out in front and saw something happening, and kind of, you know, rather than the sort of the rearguard defense but other examples where business got out in front of a change rather than waiting for it?

David Vogel: Yeah, the real fascinating part of the California story and I think a key to California's environmental leadership has been the support of business in so many places at so many stages. Yosemite, for example, was protected at the initiative of the steamship industry, which wanted to encourage tourists to come to California and visit Yosemite. The big supporter of protecting and expanding the national parks and the Sequoias and the Sierras, was the Southern Pacific Railway, which wanted people to come to California and visit the trees. The drive to curb automobile emissions in L.A. was driven by the Los Angeles real estate community, which feared that unless air quality improved people wouldn’t continue to go to L.A. and their whole business model would end. The drive to get rid of oil drilling on the beaches of Southern California was driven by Southern California real estate tourist developers who wanted that to be a pleasant area. So throughout California's history you have businesses on both sides. And alliances between citizen groups and businesses have been central to California's environmental leadership. And you see this now of course in climate change where you have Tesla, a huge clean tech sector or huge renewable industry sector, you have a whole segment of the business community which has a financial stake in moving California forward on climate change regulation.

Greg Dalton: David Vogel, professor emeritus of business and politics at the University of California Berkeley, and author of California Greenin’: How the Golden State Became an Environmental Leader. We also heard from Huey Johnson, former California Secretary of Natural Resources and founder of The Trust for Public Land; and Jason Mark, editor of Sierra Magazine and author of the book Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man. You’re listening to Climate One. California's iconic place in global popular culture is built on the availability of water, much of it transported from far away. The state’s water system was built in the 1960s and 70s when the state had about half the number of residents it does today.

Mark Arax: In my lifetime the populations of California has gone from 11 million to 40 million. And the system wasn't designed for that; the system’s certainly not gonna see us into a future of more houses and more almonds. So something has to give.

Greg Dalton: Mark Arax is the author of The Dreamt Land: Chasing Water and Dust Across California. He’s joined on the Climate One stage by Faith Kearns, a scientist with the California Institute for Water Resources, and Diana Marcum, who covers water, wildfire and drought for the Los Angeles Times. In his book, Mark Arax calls the invention of California a “mad act of hubris.”

Mark Arax: We took the edge of a continent a thousand miles long and we drew a line around it and called it a state. And then we proceeded to try to make each different state of nature inside that, there's a dozen of them, equal. And so that the invention of California required the invention of a system to move the water from, you know, 750,000 miles. And so I think that qualifies as hubris.

Greg Dalton: So that hubris that you write about, you know. Tell us a little more about that and how it's manifest with the system we’re living with today.

Mark Arax: It starts with the first taking which is the taking of the body of the native Californian. We had the most concentrated population of indigenous anywhere in North America 300,000 natives. And when Father Serra came up through Mexico and started his missions that was the taking of the body of the Indian and that allowed for the taking of the rivers. And then we see Sutter coming in to Northern California, gold being discovered -- that's the first, you know, the mining of gold is really the mining of water first. And so you see the flumes which are nothing but irrigation canals made out of wood. You see dams and ditches and this really intensive experiment going on to move the water so it has a great deal of erosive power to unearth the gold. And then at some point in the 1880s, the silting of the rivers end up damaging, doing great damage to the alluvial plains and California has a choice. Do we mine gold, do we mine soil? And so the industrialists who made all the money off gold they end up living in Nob Hill in San Francisco and farming the hinterlands and they plant wheat. So that was the industrialization beginning from mountain down to valley floor.

Greg Dalton: Diana Marcum, during the drought you wrote about a number of characters quite vividly that earned you the Pulitzer Prize. What are some of those characters whether it's Diana Johnson or Fred Lou John or others that -- tell us their story, you painted these very vivid portraits during the drought.

Diana Marcum: When the drought first started, not everybody knew about it. It hit the outlying agricultural towns first. And there was just this incredible hardships there that people were pretty unaware of even in Fresno, you know, certainly not in San Francisco and not in Sacramento, where it would've maybe mattered. And there were people whose wells were going dry and there was no civic organization, you know, responsible, no government organization because it’s your own well. So they would call and there was nothing to be done but people didn't -- I don’t think anybody official understood how much suffering was out there. And then this one woman’s well went dry and she started thinking well I wonder how many other people's wells are drying. So she started going on these roads that nobody drives out to the mobile home out to the places that are really off, you know, off the beaten track. And she found out all these people that didn't have water and then she thought well as long as I'm counting I’ll bring them some water. So then in their little local paper she had them put a notice with her phone number and her address and said she was doing this in case anybody wanted to bring water. And the next day she came out of her house and her whole backyard and her garage was just full of pallets of water because people knew, they knew how bad it was. So that kind of sticks with me. And then after the drought left the Central Valley and kind of moved on to the rest of California, I moved on to another project. Where a photographer named Rob Gossi and I we just drove around California with no particular plan, kind of doing this Tumblr thing, just live to see how much the rest of California was aware of what was going on, which was then the nucleus of it. And it had hit everywhere and there were just these random stories that would even now are just kind of burned into my mind like we’re driving down the road and we see this old man with a bucket of water, watering his rose bushes. And it was a rose that his wife who had died had planted and he was trying to keep it alive during the drought. So he would wash his dishes and then he would the leftover water to water this rose that meant so much to him. All these people that were making these tremendous personal sacrifices and using hardly any water. And at the same time like that’s not gonna make a difference, right. All of the people that you are writing about are the ones that could maybe, possibly change things. But there's these other people making these just horrible, horrible choices.

Greg Dalton: And we’ll get into that. So there’s a huge users of water and the small users of water and there’s the others. The disparity in water like there is a lot of other things, wealth and power in our state and country.

Diana Marcum: But I think there’s also that, you know, there is sort of a rural small-town thing that you take care of each other. So, you know, if you're living by like Oroville, which is one of the lakes that provides a lot of water for California and you're watching the boats on dry land and you’re watching it drop and you know that's the water people drink then you start throwing in and doing your part.

Greg Dalton: Faith Kearns, let’s bring climate into this conversation. How much is, you know, climate contributing to these, you know, the stress. Mark Arax has said that it’s kind of crazy to build California the way it was in a certain period. Now climate is kind of making that equation different. How is it changing the water equation?

Faith Kearns: I think we have a growing sense that our particularly our water infrastructure was built for a very different time when there was a lot more water coming down and particularly snow, so precipitation in general. And so what we're seeing is that as temperatures warm which every year over the past many years has been the warmest year on record and then the warmest year on record. The way that we’ve built our water infrastructure to essentially have these large dams that capture snowmelt and are intended to do that gradually over the course of the dry summer, the dry season in California, you know, is really challenging when more of that precipitation is falling as rain. And so what we saw on 2016 when we had a particularly rainy year that kind of ended the drought was that, you know, we ended up with an emergency at Oroville, right because there's too much water. And so things are --

Greg Dalton: So it was that dam that almost burst, yeah.

Faith Kearns: Yeah, I mean there were a lot of other things going on there but it does challenge our basic ability to kind of think about water in the way that we’ve always thought about it.

Mark Arax: I think to use a cliché the canary in the coal mines. We got Florida, we got the Mississippi, you’ve got California. We don't need climate change to swing wildly between drought and flood. Early in my book, I list the drought years and the flood years and it goes on for several sentences. So when you're that inherent kind of nature that we have and then you add on to that it links up to climate change. We’re gonna see havocs that have never been created before and we’re seeing that already. We saw in Paradise the whole place burning off the California map. So I think we’re going to be showing the way for the rest of the country. And so I think it's important to pay attention to what California is doing right and wrong.

---

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about water, weather and wildfires. This is Climate One. Coming up, we’ll hear about the ethics of managing scarce water resources.

Diana Marcum: This is dystopian, this is people trying to make billions and billions of dollars on there not being enough water to even drink.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about water use in the west with Diana Marcum of the Los Angeles Times; Faith Kearns of the California Institute of Water Resources; and Mark Arax, author of The Dreamt Land: Chasing Water and Dust Across California. Farmers in the central valley have been hard hit by the drought. In recent years we’ve seen a push away from flood irrigation toward drip irrigation as means of conserving water. But now, Faith Kearns and other experts are flipping on flooded crops.

Faith Kearns: You know, for a long time there was a focus on water use efficiency and that's where sort of drip irrigation technology came from, right. You used to just irrigate in furrows or flood or that kind of thing and so the idea was, oh, if we can just make every drop work to its fullest and then things will be good. And then I think what’s happened over time is people have seen that water use efficiency isn’t the same thing as water conservation, right. So what people have been doing is instead of just using their water efficiently, they take what they have saved and apply it to something else. So there is no sort of like net water conservation happening. And then the other thing that sort of come up in the last few years is just related to again and Mark has written extensively about groundwater withdrawal and subsidence which is land sinking in the Central Valley. And the fact that drip irrigation is so efficient that it doesn't help us to recharge groundwater in any way. And so now what you’re seeing is people making a move back towards studying how flood irrigation back to the beginning sort of full circle can be used as a groundwater recharge tool.

Greg Dalton: Mark Arax, this sounds crazy because we’ve done conversations here about kind of shaming farmers for flooding. Spend money to drip and now, no, go back to flooding, that’s just --

Mark Arax: There this just paradox of drip. The farmer, his yields are so much higher with drip that he takes those lines and he goes uphill now where farming never was. And then he's taking up land that is so poor that it wasn't even for pasturage. But because the drip can deliver a precise dose of water and chemical to a root zone, you don't need good earth. So they’re farming that if you look at the footprint of agriculture in the Central Valley it's gone from the primo alluvial plain soil that was when the rivers were first taken turned into canals. And then when the advent of the turbine pump came in 1920, the year my grandfather arrived here, then you started seeing the extraction of the aquifer. And you started seeing the footprint of agriculture go from prime land to not so prime. And now with drip we’re actually farming millions of acres of poor land. And this is the land that will probably come out of development when the groundwater regulation law goes into full effect.

Greg Dalton: So are you saying that's a good thing or a bad thing, you know, making water go further and it’s getting food off of land that didn't previously produce food.

Mark Arax: Well, when the resources finite then you have to make choices. And so on the San Joaquin Valley they're gonna have to choose which land deserves that water. And you will see in the San Joaquin Valley there's 6 million acres of farmland it'll probably go down to 4.5 because they've decided to idle the land that an argument can be made, a strong argument should have never been farmed in the first place. It's alfalfa, it's Holsteins; we need to find a place other than California that where cows are truly happy because our land and water is too valuable for Holsteins.

Greg Dalton: California has abundant water this year but some investors are betting that water constraints in the future will drive prices upward. Ry Rivard covers water and power for the Voice of San Diego. He’s reported on land and water rights purchases in Southern California that suggest speculation by some unusual investors. Over the past several years, a company called Renewable Resources Group has bought land in the Imperial Valley. In one case, it re-sold land within a couple of years for about double the price to the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which provides water to nearly 20 million people. We talked to Ry Rivard about what these secretive deals worth hundreds of millions of dollars might mean for the future of California water.

[Start Playback]

Ry Rivard: If you look at the Imperial Valley in particular, it's really desert. The only reason it's a big farming area is because they diverted the Colorado River into their Valley. Renewable Resources Group this Los Angeles-based company that does water, land and energy development. Renewable came in working with Harvard as the sort of silent partner the Harvard Foundation and bought a bunch of land. They knew that people were interested in the water that came with this land. We’re talking, you know, multi-million-dollar deals for thousands, tens of thousands of acres of land. So much of water in California a lot of this water trading happens beneath the radar. There could be other companies that we don't even know about. There’s so little freshwater in the world some of it is getting polluted some of it is being rearranged by climate change in unpredictable ways. So betting on making money from water is a good bet as water becomes scarcer. I think we really need to start paying more attention to who these people are who these actors are who these lobbyists and officials, many of them unelected are and who these companies are. And if we don't I think we could find ourselves subject to prices in situations and scarcity real or artificial that we could've prevented or dealt with or anticipated if we’d just been paying more attention

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: That was Ry Rivard from the Voice of San Diego. Faith Kearns, water markets are controversial, but water is unique in some respects as both a commodity and the UN has declared a human right to water. So it's both a right and a commodity. Your take there on sort of, you know, investing; is that necessarily bad to be trading water rights?

Faith Kearns: So I’m not a money person I’m an ecologist by training. And so for me, yes, I think it’s a bad thing. Do I have some other solution per se? No. I am not a huge fan of the water market conversation. I think for me what I’ve, you know, kind of come to over the last many years of working on this issue in California is that there is a lot of stuff that goes on really behind the scenes and that is completely inaccessible to most of us even those of us who work on this topic professionally. In a way that’s pretty disturbing for me. And I think, you know, I’d actually like to see us move in a completely different direction which is back to the idea of, you know, water really as a public -- I don’t even like the word resources how radical I’m getting these days is, you know, it belongs to all of us. And so this idea that you've got kind of the 1%, you know, capitalizing even further on this finite resource is incredibly disturbing to me. And I am really grateful for people like Ry and Mark who actually spend the time to kind of figure out what's going on behind the scenes. I’ve sat with certainly colleagues, talking about how we feel, you know, like our hands are tied behind our back a little bit because we aren’t operating in that same financial space that other people are. And we’re kind of running around trying to do the best we can, but also these forces are so much bigger than any of us.

Greg Dalton: Mark Arax. We live in an economy where most everything is traded there's marketplaces for all sorts of things, parking spaces, etc. But somehow people think differently about water.

Mark Arax: Selling water. It is a problem -- it belongs to all of us but this water like Imperial it was captured before 1914, they have these rights to use that water beneficial use. And we have, I won’t get in all the complexities of it but we have this very weird water law out here. It's a combination of appropriative rights. In other words that you could take a river and take that water via canal to some farmland far away if it's beneficial use. And then also you can use it along the riparian corridor, riparian rights and we have a kind of combination of those two. Selling water, I don't mind if it's farmer selling to farmer. What really bothers me is farmer selling to city. The farmer can never compete with the cities for that water. And if that water leaves the farm belt and ends up going up and over the mountain so L.A. can build more houses across the desert, that's to me a problem. But that's the farm boy in me going back a few generations talking.

Greg Dalton: There’s a whole sort of urban coastal versus the inland farming tension in California water wars. There’s a lot there --

Diana Marcum: But this kind of stuff goes beyond that. I mean this is dystopian, this is people trying to make billions and billions of dollars on there not being enough water to even drink. I mean I was there when the UN came to some of the smaller towns in the East Valley, I mean the UN came to California because people don't have drinking water. How can we even discuss it? I have like, it’s hard for me to even think of it in a calm sort of way because I just have these snapshots. I remember the first time all the almonds came in. We were having dinner and we were both exhausted because we’d both been covering drought forever. And there was this one moment where it’s like who’s putting these almonds in, where's the water coming from? This was like the absolute height of the drought and every time you drove down the road here we’re more and at the same time, it was the same year that the UN is in another part of the valley because people don't have drinking water. And person after person is getting up and saying, I spend 30% of the money that I make as a farmworker. I mean they’re really physically going thirsty they don't have enough water to drink, they can't give their babies baths. And then the same time, you've got these backroom deals that you’re tracking down.

Mark Arax: The water became a means by which the Valley became one of the most unequal places in the world.

Diana Marcum: But now they’re treating it like oil they’re just gonna be trading it.

Mark Arax: So that’s something that we have to confront. How those trades happen, are you allowed to sell to urban at some, you know, already there’s a farmer named Vitovich [ph] he’s not really a farmer he’s a developer from Silicon Valley up and over the mountain to the San Joaquin Valley, buying up all this farmland but he doesn’t care much about the farmland, he’s farming temporarily, it's the water. And he’s already sold a chunk of it for $75 million to the folks in Mojave so they can continue to grow. It's, you know, I don’t want to date myself but in my lifetime the populations of California has gone from 11 million to 40 million. And the system wasn't designed for that, the system’s certainly not gonna see us into a future of more houses and more almonds. So something has to give. And the system is cracking and that's what I basically do in my book I go inside those cracks both historical and present, big farmer, small and try to figure out how did we get to this madness and where is this madness taking us.

Greg Dalton: Diana, you covered the Rim Fire and you said you are changed forever. And I also like to give you a little more space to talk about the emotional impact of the joy of this wet year and the beauty but knowing it won't last.

Diana Marcum: So I'd been covering drought and I've been seeing all of these traumas and I'd also been seeing all this resilience and hope and the best of humanity. So it was moving on all levels. And then I think probably about when I was as tired as I thought I could be, the Rim Fire broke out which, you know, now we’ve been through Paradise. But I think what was scary about the Rim Fire even at the time was that I knew Paradise was coming. So we were in a little town where you could see it, it’s right on the edge of Yosemite. And every night this cloud, you know, fires they create their own weather and this cloud comes up and inside the cloud there's lightning that starts more fires. You can explain it better than I can probably but the bottom line is it is just hellishly scary. So, and it comes every single evening. So we were staying in this cute little town, you know, with the white picket fences and have you seen my lost dog and, you know, life. Life is all around you, there's geraniums in the flower box it's there. But at the same time, certain time at night we'd all walk out into the middle of the road and just wait for this gigantic cloud to come out, it's just larger than if you haven't seen it with your own eyes, I don't know if I can -- you both seen them, right. I mean it towers it's taller than the Sierras. And at the time the firefighters didn't know if they would be able to fight it, and it was the first time I'd ever heard firefighters even admit to the possibility of defeat. So I don’t think that's ever going to leave me, yeah, that stayed.

Greg Dalton: Faith Kearns. For people who live in the American West, you know, we’re talking about issues in California but these issues some of them apply beyond the boundaries of California. Talk to us about fire and affecting water quality. Sometimes we talk about fire we talk about water, let’s talk about them together.

Faith Kearns: Yeah, I mean I think it's been a really interesting evolution in my sort of career I've been out of, you know, I’ve been a professional for 15, 20 years at this point. And when I was in graduate school there were people who are sort of like, oh, I wonder how water affects riparian areas. So, you know, the near stream and fish and things like that. And that was kind of as far as it went, even that was a very small field of study. And I think what we’re seeing right now is this really interesting thing where fire, it sort of moved out of urban areas, you know, after the 1906 earthquake, we learned how to sort of keep houses from burning down in urban areas moved into the sort of wildland fire urban interface thing. And now what we’re seeing is that fire is actually maybe beginning in a wildland area but then burning down, you know, it becomes urban conflagration. And that has brought up a whole new set of water concerns in the last few years that just are completely new in a lot of ways. Every day I’m reading stories about the water system in Paradise and that was true in the Tubbs Fire in Santa Rosa as well that there was benzene found in the water system and we’re seeing the same thing in the Camp Fire. And there are academics who are critiquing even the protocols of how the state measures whether water is considered safe. So I think we’re gonna see, you know, more than just the idea that if it's wet or maybe we won't have as much fire or maybe we'll have more because there's more grass. It's really getting into this much more sort of what I think about as a public health issue where, you know, it’s not only smoke and all these things that are happening with fire but it is also literally, you know, really becoming a broad public health issue with water implications that are much deeper than I think many of us had thought.

Greg Dalton: You’ve been listening to Climate One. We’ve been talking about California’s climate legacy and water woes with Faith Kearns, a scientist with the California Institute for Water Resources, Diana Marcum of the Los Angeles Times; and Mark Arax, author of The Dreamt Land: Chasing Water and Dust Across California.

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast at our website: climateone.org, where you’ll also find photos, video clips and more. Please help us get people to talk more about climate by giving us a review wherever you get your podcasts.

Greg Dalton: Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Sara-Katherine Coxon is the strategy and content manager. The audio engineers are Mark Kirchner, Justin Norton, and Arnav Gupta. Devon Strolovitch edited the program. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, where our program originates. [pause] I’m Greg Dalton.