Faith in Climate Progress

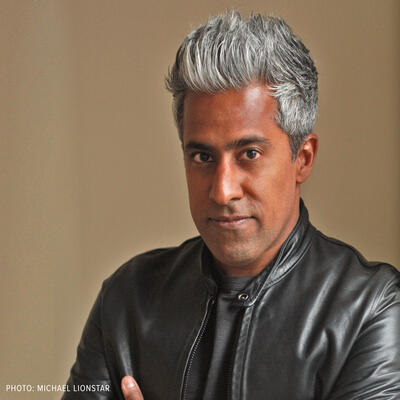

Guests

Celia Deane-Drummond

Jennie Rosenn

Iyad Abumoghli

Summary

It’s been ten years since Pope Francis issued his landmark encyclical on climate and caring for our common home, Laudato Si’. That call to people of all faiths is widely considered to have helped spur world leaders to achieve the collective commitment known as the Paris Agreement, which pledged to limit global temperature rise to “well below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels,” with the goal of holding the line at 1.5 degrees. Ten years later, countries are struggling to take action in line with their promises. This raises the question: When governments fail to take meaningful climate action, what can faith leaders do that diplomats and elected officials can’t?

According to the Pew Research Center, about 75 percent of the global population follows a religion. And faith can be a powerful force to drive human action.

“What determines the behavior of people is their culture, their upbringing, is their beliefs and their ethical values,” says Iyad Abumoghli, founder and former director of the Faith for Earth Coalition with the United Nations Environment Programme. He’s also founder and chair of Al-Mizan, an Islamic approach to protecting the environment and addressing climate change that takes inspiration from Laudato Si’.

Celia Deane-Drummond is director of the Laudato Si' Research Institute and senior research fellow in theology at Campion Hall at the University of Oxford.

“What Pope Francis believed was that the climate crisis wasn't just a technical crisis that was somehow happening and we couldn't do anything about it. It was a wake up call to see that actually we are responsible as human beings collectively for what is happening to our common home,” she says. “As far as he was concerned, the western world was caught up in over-consumerism, indifferent to the suffering of others, including the suffering of all creatures and those who are being affected most by climate change.”

The Catholic Church is not alone among religious institutions in its directives to care for creation. Organizations like Interfaith Power and Light, the Hindu Bhumi Project, and the Buddhist Climate Action Network demonstrate the universality of creation care as central to religions worldwide.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn is founder and CEO of Dayenu, a group that organizes the American Jewish community to address the climate crisis through political action. She calls the climate crisis an “issue of the soul.”

“It's also a moral crisis. It's about valuing human life and our planet over corporate greed, and the ability to continue, in Jewish tradition, l’dor vador, from generation to generation, and that all people can thrive no matter where they live. So protecting the most vulnerable, calling out real villains like the fossil fuel industry, lifting up the way the climate crisis disproportionately impacts certain communities,” she says. “All of these core moral issues, religious communities and leaders, I think are very well situated to do this and to do this grounded in values and teachings.”

Episode Highlights

00:10 – Quick update on COP30 conclusions

03:40 – Celia Deane-Drummond explains importance of Laudato Si’

08:15 – Will Pope Leo continue Pope Leo’s environmental legacy?

11:00 – Role of religion and ethics in climate conversations

17:45 – Rabbi Jennie Rosenn explains Jewish concept of Dayenu

20:30 – What religious leaders can do that political leaders can’t

26:30 – Rosenn on deregulatory agenda of EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin

37:45 – Iyad Abumoghli on how religion shapes human actions

40:30 – Al-Mizan’s origins and approach

51:00 – Faith and political leaders meeting to discuss the role of faith and values in facing climate change and climate justice

54:40 – Climate One More Thing

Resources From This Episode (6)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Ariana Brocious: I’m Ariana Brocious.

Kousha Navidar: I’m Kousha Navidar.

Ariana Brocious: And this is Climate One.

[music change]

Ariana Brocious: COP30, the global annual climate summit, recently wrapped up in Belém, Brazil. And without a lot to show for it. A lot of nations had hoped countries would adopt language pledging to transition away from fossil fuels. But they didn’t.

Kousha Navidar: That’s wild. We’re talking about a United Nations climate conference. And the words “fossil fuels” didn’t even appear in a final agreement until two years ago. And still world leaders can’t agree to promise to get off of them?

Ariana Brocious: Right. There’s a lot of pressure from fossil fuel producing countries. However, countries did agree to triple the amount of money promised to help poorer countries adapt to climate change, though on a slower timeline than many had hoped.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. It’s disappointing, to say the least. Which has more people questioning the value of this annual conference altogether.

Ariana Brocious: There has been some progress over the years. Ten years ago, at COP21, leaders in Paris agreed to limit global temperature rise to “well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels,” with the goal of holding the line at 1.5 degrees. And since then, the rate of climate pollution growth has slowed.

Kousha Navidar: Also ten years ago, Pope Francis issued his landmark encyclical on climate, Laudato Si’. Many say that document – a call to action for all people of the world to protect our common home – helped spur those world leaders in Paris to come to that agreement.

Ariana Brocious: And that has us asking today: If political leaders are failing to take meaningful action, what role can religious leaders play? Many are hoping that the new Pope, Leo XIV— will follow in Francis' path. And the Catholic Church isn’t the only religious institution that encourages its followers to care for creation.

Kousha Navidar: A few years after Laudato Si, Muslim leaders issued Al-Mizan, which draws on principles from the Quran on protecting nature. And there’s all these other groups: the Jewish group Dayenu, Interfaith Power and Light, the Hindu Bhumi Project, and the Buddhist Climate Action Network – all demonstrate the universality of this idea of creation care.

Ariana Brocious: According to the Pew Research Center, about 75 percent of the global population follows some religion. But regardless of your personal spiritual beliefs, one thing that struck me in putting together this episode is that all of these faiths view action on climate and environmental sustainability as a moral imperative. And that moral framework is something most of us can agree on.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah in fact, Rabbi Jennie Rosenn, who I talked with, described the climate crisis as a moral crisis. So today we’re talking about paths to progress led by faith traditions.

[music cue]

Ariana Brocious: Let’s start with Celia Deane-Drummond. She’s the Director of the Laudato Si' Research Institute and Senior Research Fellow in Theology at Campion Hall, University of Oxford. She helped me understand what Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato Si’ is and why it was so groundbreaking when he wrote it ten years ago.

Celia Deane-Drummond: What Pope Francis believed was that the climate crisis wasn't just a technical crisis that was somehow happening and we couldn't do anything about it. It was a wake up call to see that actually we are responsible as human beings collectively for what is happening to our common home. By the common home, he meant the home of all people and other creatures as well, and the people who are most severely affected of those in the global south. So he had a particular care for those living in the global south. Not just because he was an Argentinian himself, but also because he'd spent hours sort of talking to those in the Amazonian region and other places, and he'd witnessed firsthand the sort of degradation that was taking place in some of those countries. So he suddenly, as he said himself, he got how the ecological issues are joined up irreversibly with social issues and social justice questions, as far as he was concerned, the western world was caught up in over consumerism, indifferent to the suffering of others, including the suffering of all creatures and those who are being affected most by climate change. He also pointed out that technologies and what he called the technocratic paradigm, was sort of throttling societies so that they no longer really knew how to act. They presuppose that our technologies would provide the solutions when actually it was a much deeper moral and spiritual problem that he was identifying. He was trying to push cultures in the western world in particular to go through what he called a cultural revolution. I mean, it's a very radical encyclical in many ways. It was addressed not just to Catholics, but to all people of goodwill, including scientists. There was more science in this encyclical than any other encyclical before or since. Which is another amazing thing about it because he was also a scientist by training, a chemist.

Ariana Brocious: It is interesting because there's often a real or perceived conflict between science and religion. And so to have a pope who is a scientist by training, really embrace and sort of advocate for that within a religious document is especially interesting. And Pope Francis was a radical in a lot of ways. He broke with tradition in many ways. I can think of notably his rejection of a lot of the trappings that come along with the papacy, right? Some of the kind of fancy cars and stuff like that. But when we speak about his leadership specifically in climate and an environmental sense. Can you point to a few specific examples where his leadership did shift policy or behavior at scale?

Celia Deane-Drummond: Yes. I think one of the most important things is the timing of when he released this encyclical in 2015. It was just before the Paris COP 21, conversations and agreement took place. And I think that he did influence that conversation. You know, something happened in the Paris Agreement that people weren't necessarily expecting in, in that it went a bit further than many people thought. Of course, he was also, like many others, quite frustrated with the extent to which that agreement has been monitored and implemented. And so when he wrote Laudato Diem, which was a sort of exhortation just before the Dubai COP 28 Summit in 2023, he expressed his own frustration that his comments about what Paris might achieve, you know, hadn't really done as much as he intended or hoped. But again, I think he helped shape the conversations on the ground in these international agreements. In addition to that, it also influenced the extent to which indigenous communities need to be taken seriously.

Ariana Brocious: Hmm.

Celia Deane-Drummond: Although many indigenous peoples don't think that their voice has been heard enough, they are now being recognized, at least in a way that wasn't the case, you know, five, 10 years ago and I think that's, not only down to Pope Francis, but he was one of the many influencers that pushed that agenda and said, we really have to listen to alternative forms of knowledge from those who have, if you like, found a way to live alongside and be in harmony with the the natural world.

Ariana Brocious: This year also marks the beginning of a new papacy. Pope Leo was elected in May. What evidence are you seeing so far that Pope Leo will continue Francis' environmental mantle?

Celia Deane-Drummond: Like Pope Francis, he's concerned issues of poverty, and as he's also, spent a, you know, half his life in, in Peru as well, he was able to bind up that concern for issues of poverty with concerns for issues of the climate, the two in intricately linked. He's said on a number of occasions that he's gonna continue with Pope Francis' legacy. And so we can expect that, I don't think he'll introduce any more changes than Pope Francis has, but he's trying to mediate, if you like, within the church what Pope Francis intended.

Ariana Brocious: You mentioned that there are tenets maybe underlying the Laudato Si’ and, and the way that Pope Leo has continued some of that legacy. Especially at a time when governments are falling behind on taking meaningful action, what influence can the great religions wield toward climate progress?

Celia Deane-Drummond: I think that always within a religious tradition, they're gonna be some who disagree. But on the other hand, I think that they have the capacity to enable a kind of mass movement and also underline a deep desire for change and action that comes from a deep spiritual root in a way that's sort of distinctive for that particular religious faith. That sort of desire of that change of heart, if you like, that's possible within a religious tradition, that conversion, if you want to call it that, is an ecological conversion. And I think it goes very deep in the psyche of people who are religious.

Ariana Brocious: Many would say that environmental destruction has roots in a long history of extractive colonialism, and this is something in which the Catholic Church historically played a significant role. So how do you think the church can overcome its past endorsement of extractive colonialism and reclaim that moral authority?

Celia Deane-Drummond: This is something that we are actively involved in at our, in our research institute, the Catholic Church and mining, and some of the social issues around the Extractivism industries. So I would say that because it's a sort of social justice issue, it's of fundamental importance to Catholic social thought. The fact that, Catholic Church was involved in this in the past is to their shame. It wasn't putting into practice the fundamental aspects of its teaching. So obviously there's room for the church to say that we made mistakes in the past and we need to turn around.

Ariana Brocious: Many climate conversations focus on technology and policy. What essential questions are we missing when we leave theology and ethics out of those discussions?

Celia Deane-Drummond: Yes. I think it, it, it goes a little bit back to some of the earlier parts of our conversation where the technocratic paradigm, as Pope Francis put it, isn't enough to solve the problem. It's enough to try and generate a sort of scientific solution, but if people don't come on board and don't endorse it, then nothing changes. And I think that one of the frustrations that many scientists have had, and I've spoken to a number of them over the years, being a scientist myself by training originally, is that, that, you know, why don't people listen to the knowledge? Um, the reason why they don't is that however much information you give people, they're not gonna change their behavior or their hearts or their way of looking at things. There has to be something else that challenges them then to move. and that sort of ecological conversion can come from, from a religious route. and that's why I think it's fundamental that theologians, you know, such as myself and others actually, you know, helped people to understand how important it is to put, um, issues of creation and social justice right into the heart of, of their teaching. If Christians start to understand that it's part of their fundamental Christian identity, it's not just an optional extra, then I think that we're going to see real change and real movement towards taking this, even more seriously than it's been taken already.

Ariana Brocious: If you could get every climate activist, policymaker, and concerned citizen to grapple with one theological or ethical concept, what would that be and why?

Celia Deane-Drummond: Oh, um,

Ariana Brocious: Just an easy one.

Celia Deane-Drummond: Yeah, you got the sting in the tail at the end of this. I think all things are interconnected, so, so it's the, this weaving in issues of social justice with issues of ecology and seeing that as the fundamental. insight that we need to grasp that the breakdown of our relationship with each other and with the natural world has come from the breakdown in our relationship with God. So it's about the healing, if you like, of ourselves, of our relationship with others, our relationship with the creation, our relationship with God. And that reconciliation is something that theologians have been pressing for, for centuries. But now it applies on a bigger scale to, to the globe as a whole. You know, we need to work for the common good. The science needs to work for the good of all, and not just its own agenda. Nations need to work for the good of all and not just their own agenda. Individuals need to work for the common good and not just their own selfish consumerist habits. So we all need to change and start thinking more broadly and more, inclusively of what our actions are gonna do to affect others and to affect the natural world around us.

Ariana Brocious: Celia Deane-Drummond is Director of the Laudato Si’ Research Institute and Senior Research Fellow in Theology at Campion Hall at the University of Oxford. Thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Celia Deane-Drummond: Thank you so much for having me. It's been a real pleasure to talk to you today.

Music: In

Ariana Brocious: Coming up, Rabbi Jennie Rosenn on how her faith helps guide action on climate:

Jennie Rosenn: Ultimately the climate crisis is about closing the gap between the world as it is and the world as it could be, or frankly as it should be. And faith, I think, is really also about holding strong to a vision of a world transformed.

Ariana Brocious: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: Help others find our show by leaving us a review or rating. Thanks for your support!

Music: Out

Kousha Navidar: This is Climate One. I’m Kousha Navidar.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn has spent more than two decades leading Jewish non-profits that advocate for social change. She’s founder & CEO of Dayenu, a group that organizes the American Jewish community to address the climate crisis through political action.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: The climate crisis is coming more quickly and more furiously than I think really all of us had imagined. I think many scientists are even sort of shocked at the pace of acceleration. I also think that the climate crisis is both a political issue, It's obviously an ecological issue, and I also think that it's an issue of the soul. We know that more than 80% of the American Jewish community is concerned or very concerned about the climate crisis. That's actually a statistic from a number of years ago. It's significantly higher now, and I think there are two reasons, at least two reasons why more folks don't engage. I think one is people don't know what to do in the face of such a complex issue. And the second is that it is so overwhelming on a spiritual psychological level to imagine what the world will be, uh, what the world already is for many, many people, what it's becoming for many, many more of us and what it will be for our children and grandchildren. And so I think there's a way in which we disassociate or look away and get busy with our lives because it's too much for our souls to bear what's at stake. And so, as I was having my own realization about just how quickly and devastatingly the climate crisis was coming, how it is an issue of social, economic, and racial justice, how the Jewish community was not mobilized in all its people in power at the scale that's needed. I was coming to realize that we needed to create an organization and a movement that was addressing both of these reasons for an action. Giving people strategic ways to take action in community and spiritual resources to really make the space to confront the climate crisis with our eyes and hearts open.

Kousha Navidar: Jenny, this is one of the reasons why I was so excited to get to talk to you, because when I hear you say that. Climate is a matter of the soul, and it can be overwhelming, it resonates with me, even though that's not how I necessarily think about it. You know, like I talk to so many people in the climate space nowadays, and it does feel overwhelming. There are so many statistics and stories and human experiences, but an issue of like where I put my own faith and where the idea of who I am as a, not a person, but of something larger than a person. It is a matter of the soul. I just, it's a, it's really beautifully put, not an angle that I think about a lot, and so it makes perfect sense that you would start this organization, call it dayenu. Which I understand is a big word in the Jewish faith. I wanna talk about that word a little bit. I have been to a Passover. I am familiar with the term,

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: You've sung the song.

Kousha Navidar: I have sung the song. But you know, for our listeners, for me as well, I wanna know, what does the name Dayenu signify in the context of climate action?

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: Yes. So Dayenu, as you referenced, is a really joyous song of gratitude that we sing each year at the Passover Seder when we retell the story of the Jewish people's journey from slavery to freedom. So it recounts all the things that God has done for us. If God had taken us out of Egypt, but not given us the Torah Dayenu, it would've been enough. It's usually how it's translated. It would've been enough. It also means we've had enough. We've had enough destruction, we've had enough valuing fossil fuel companies over human life. We've had enough letting the impacts fall disproportionately on black, brown, indigenous, poor, marginalized communities – dayenu – enough. But there's also a double entendre because it can mean. We have enough. We have what we need to confront the climate crisis and to move towards climate solutions. We have the resources, we have the policy rubrics, we have the technology, we have what we need so that everyone can have enough.

Kousha Navidar: Mm. We've had enough and we have enough. The Jewish tradition also has deep roots in concepts like stewardship, concepts like repair of the world. I'm sure that also informs your climate work as well.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: Absolutely. The concepts that you mentioned of shomrei adamah, protecting the Earth and bal tashchit, don't waste, are foundational, really Jewish environmental concepts. And I think there are many other values that also are profound kind of foundational Jewish values that come to inform our work and, the work of confronting the climate crisis as a Jewish community and as communities of faith. This is a social justice issue, tirdof tzedek pursuing justice, protecting the most vulnerable, choosing life and at the most core living l’dor vador, living from generation to generation. The very idea that the generations continue through time, and all of these really come to inform, the call to take action in addressing the climate crisis and doing it in a way that also centers values, like protecting the most vulnerable, like justice, like ensuring that all people can live and thrive.

Kousha Navidar: This is getting to the heart of the conversation for me because a question on my mind is what role religious leaders can play that other leaders can't. So for you as a religious leader, just thinking about it broadly, thinking about faith, what role can religious leaders play that politicians, scientists, activists can't as well?

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: This is one of my favorite questions, because I believe, as you said, that there is so much that faith communities and faith leaders contribute to confronting the climate crisis and, and, and to the climate movement more broadly. I'll start. Most fundamentally, the climate crisis, I said earlier, is an issue of the soul. It's also a moral crisis. It's about valuing human life and our planet over corporate greed, and the ability to continue, as I said, in Jewish tradition, l’dor vador, from generation to generation, and that all people can thrive no matter where they live. So protecting the most vulnerable, calling out real villains like the fossil fuel industry, lifting up the way it, the climate crisis disproportionately impacts certain communities. The stark reality of environmental racism that affects millions of people. All of these core moral issues, religious communities and leaders, I think are very well situated to do this and to do this grounded in values and teachings.

Kousha Navidar: Hmm.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: So that's, that's the, the moral voice, the moral role.

Kousha Navidar: Well, yeah, to talk about the moral role too. I want to touch on that for a second. Sorry to interrupt you, but there's the trust there that I think is very important as well, like the trust between a leader and their community to actually talk about these moral things, right?

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: Yes. And to be rooted in community and to be rooted in a core set of shared values. I also think that ultimately the climate crisis is about closing the gap between the world as it is and the world as it could be, or frankly as it should be. And faith, I think, is really also about holding strong to a vision of a world transformed, some would say, a world redeemed. And right now we need to stop terrible things that are unfolding, but we also need to envision a different future. What the world could be. We need the power to see the world as it could be, and to truly believe that we can build a different society with a different energy system, with more justice, with more wholeness for all people. And I think this takes a kind of moral imagination to envision a different kind of future. And I think that kind of imagination of envisioning a different future and believing it's possible is the muscle of faith. And I think people need spiritual resources to grapple with the climate crisis, to keep our eyes and hearts open. And so another unique role I think for faith communities is to spiritually resource people to be open. To what is happening, not to shield their eyes, avert their eyes, and for those who are working on climate to support them and resource them for the, the long haul. This is hard, hard work, and to do that in the context of community,

Kousha Navidar: Right, 'cause you're talking about it kind of at two levels, I think I hear you tell me, but there's this community building aspect of it, but then also this very intimate, I think a term you've used before is, is spiritual adaptation aspect of it. Is that two tier kind of a good way of thinking about it?

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: I think there's a moral, political and spiritual dimension. And we say spiritual adaptation because in climate we talk about mitigation and adaptation, and I think there's spiritual adaptation that we all are in the process of doing to adjust to this very stark reality, which is so different than what many of us grew up understanding about the world and about reality. Obviously for younger generations they have grown up with this as very much the reality, but there is significant adaptation that we all need to be doing, And then just tactically. One of the unique added values that I think faith groups can play in the climate movement is that we can play both, what I would say call an inside and an outside game. So raising up a moral voice, calling on our elected leaders to act in alignment with values kind of being the agitating voice, and then to sit down with them on the inside. Building relationships. If we have time for a short story?

Kousha Navidar: Sure. Yeah, please.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: Okay. So in 2021, I and a colleague, a Muslim leader, were arrested together, along with many others, outside of the White House where we were protesting with people versus fossil fuel, the way in which then President Biden was continuing to sign off on certain fossil fuel infrastructure. So we were literally arrested by Capitol Police outside the White House. There's a picture of us being taken away. There was also a reverend there, kind of the three Abrahamic traditions,

Kousha Navidar: Right.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: in handcuffs. Fast forward. Almost exactly one year later, I run into my colleague, the Imam in the gardens of the White House. We had both been invited to celebrate the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, because we had been organizing our communities and I think that is sort of a very visual snapshot of the way in which religious leaders and religious communities both need to be outside, raising up a voice and a protest, and also people on the inside who are trusted and valued and invited in to really try to make change from the inside.

Kousha Navidar: It's so interesting to talk about that inside, outside dynamic that faith institutions can play. And I'm happy that you talked about the White House specifically because I mean, there has been so much happening from there lately with regards to climate. I mean, earlier this year, EPA head Lee Zeldin unveiled his plans to, in his words, drive a dagger straight into the heart of the climate change religion. What was your reaction when you heard those words?

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: Yeah, that was a doozy. Honestly, when I heard this, it made my stomach turn. Zeldin managed to denigrate religion, science, and the desperately needed life-saving efforts to address the climate crisis all in one, full swoop. I'm not sure what climate change religion is. I do know that Judaism, the religion, Zeldin and I share values the protection of life. and that Zeldin's actions are profoundly and continue to be profoundly at odds with another Jewish concept, which is pikuach nefesh to save a life. The values that we talked about of tirdof tzedek, of pursuing justice, v’charta b’chayyim, choosing life, all of these, dozens of Jewish values, that he is really denigrating. And even more pointedly, I think what has really galled me, it's not even a strong enough word, is the way in which he's lifted up Jewish values and practice while tearing down the foundations of our nation's climate protections. I don't know if you remember this, but he had this big public mezuzah hanging, at the office of the EPA, so he was hanging on his office doorway a passage from the Torah about the foundational Jewish value of oneness, about keeping Jewish precepts front and center at all times. And this is what the text inside the mezuzah says that we should pass them to our children. He was sanctifying the space with the mezuzah holding this scripture. While taking a sledgehammer to the very things that protect human health and our environment, it felt like a tremendous farce. And I think as a Jewish climate movement and a Jewish climate organization, we feel a particular responsibility to call out the ways in which what he's doing is completely antithetical to Jewish values.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, I mean, you didn't say the word, but hypocrisy seems to be at the heart of those actions from, from your perspective, right?

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: For sure. I would say worse than hypocrisy, I mean. Since he took the helm of the EPA, he's been dismantling decades worth of environmental protections. These are protections that help ensure basic human rights, clean air to breathe, water to drink, healthy food to eat. He's been throwing up obstacles, one after another, making it harder, not easier to transition from fossil fuels to clean energy, which we so desperately need. And now, as you know, he is in the process of repealing the endangerment finding. I still find it hard to wrap my head around the fact that the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency is now waging full on war against the climate. The endangerment finding is what establishes the scientific truth that greenhouse gas emissions released by fossil fuel cause harm. Getting rid of this. It's like tossing out the 10 commandments. I'm not even being hyperbolic. lLke by trying to eliminate the endangerment finding. Zelin and the EPA are literally trying to destroy the legal framework our country has to drive a coherent climate policy.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: They're stripping away the government's ability to regulate emissions. and part of what makes me think about the 10 Commandments is it also seems like it's like denying something that's fundamentally true about the world.

Kousha Navidar: Mm.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: Greenhouse gas emissions released by fossil fuels cause harm.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: Full stop. So what does that even mean to get rid of that finding, and to get rid of what enables our government to live and act in alignment with science and our values.

Kousha Navidar: What does it look like for you when Dayenu’s work really makes the impact that you want? Like how do you know when you're on the right track?

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: We organize, primarily through grassroots organizing. So we have dinu circles all over the country. We are raising up and training leaders, people who can move, as I often say, from angst to action. Some of those –

Kousha Navidar: I love that. Sorry, I like that angst to action. Sorry. Go on.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: Yeah, because I think that's actually, we don't see our work as convincing people that the climate crisis is an issue. Probably at this point close to 90% of American Jews, somewhere between 80 and 90%, and, and increasingly for all Americans, the climate crisis is, it's not a question of whether it exists and actually the fact that so many more people have experienced direct impacts just in recent years, has driven home just how real this is. The question isn't, is there a climate crisis? The question is how do people move from concern or angst or despair or fear or anxiety too? Action. And how do we ensure that that action is strategic and really making a difference? So grassroots organizing and really giving people meaningful ways, training people, giving people organizing skills and designing campaigns that are strategic that really focus on different levers for change. So for example, we were one of the many, many efforts to pass the Inflation Reduction Act, the historic investments in clean energy, the very thing that Trump is now trying to dismantle. We had many public actions over the course of those months leading up. being able to get politicians on record making commitments through organizing would be one metric. I think. being able to work on specific pieces of legislation at the state and federal level is another indicator. We do a lot of get out the climate vote, work with the Environmental Voter Project, and, that is very, uh, strategic work to identify low propensity climate concern voters. So these are people who, climate is their number one issue, but they don't, always vote. getting Jewish institutions to screen fossil fuels out of their investment portfolios. So those are some of the external kind of indicators. And then they're all the internal indicators. How many new leaders do we have? How many more folks are being able to really take action and organize their peers to take action? Because ultimately this is about people owning their agency and not just, worrying quietly at home, but really coming together in community to take, to take action.

Kousha Navidar: Jennie, you've pointed out that Jews have faced existential crises many times in history and have survived. So how does that shape your perspective on the climate crisis?

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: I'll start by saying, you know, sadly, Jews do not have a monopoly on having faced difficult times before, I think like many, many people's Jews have faced annihilation and faced it in a way that we've not only survived, but thrived. I think some of that has been through the kind of envisioning and building a different kind of future, and I think some of it has been through how do we cultivate courageous action. One of the things we think a lot about at Dayenu is how do we support and encourage folks to connect with our own ancestors, whether those are our great grandparents who may have come to this country in hardship situations, um, having been persecuted. Is it our biblical ancestors like Shiphrah and Puah, who risked their lives to save Jewish babies at the time of slavery in Egypt? Is it Moses who tirelessly confronted authority over and over again. Is it our ancient ancestors who embarked on the treacherous journey through the desert to build a better future. All of these are people in our own past who we're connected to l’dor vador, generation to generation who have faced existential threat. So as we face the existential threat of the climate crisis, I think we're really called to draw from our well of strength, and that includes our access to our tradition and our teaching and our values and our ritual and our practices, and also our ancestors. I think we can all benefit from thinking about the generations before us and the kind of resources that they brought to do everything we can to secure a different future.

Kousha Navidar: And you talked about this a little bit when you were talking about the work of Dayenu, but I wanna put a fine point on the connection between faith and secular climate advocates here. So how can those two work together more effectively, especially when they may have different worldviews. I mean, I, for instance, am not a religious person and I really enjoy sitting down and talking to you and I think it takes all hands on deck to solve existential problems, you know what I mean?

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: Absolutely. It's funny you use that language because I often say, this is the time where we obviously need all hands on deck, and that means that. Everyone needs to bring their people, whoever their people are, to this existential crisis. This is something that no one group or one person can solve alone. The climate crisis needs everybody and it needs everybody of all different backgrounds because we can't do it alone and we don't need to do it alone.

Kousha Navidar: In light of everything we've talked about, where do you think religious leaders can have the most influence on climate process, looking ahead?

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: I think that religious leaders in religious communities need to ensure that they're raising up a moral voice because the climate crisis is a moral issue. And how we respond to it has to be rooted in our deepest values and in a sense of urgency and cultivating courageous action because it will take courageous and collective action for us to avert the worst of climate devastation and build a more just and livable and sustainable future for all people for generations to come.

Kousha Navidar: Rabbi Jennie Rosen is founder and CEO of Dayenu. Jennie, thank you so much for joining us.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn: Thank you.

Music: in

Ariana Brocious: We’re going to take a quick break. When we come back, at last year’s global climate summit in Azerbaijan, the host country president praised oil and gas as “gifts from God.” What does a Muslim faith leader make of that?

Iyad Abumoghli: Everything is, is a gift. But of course gifts cannot be abused and cannot be overused.

Ariana Brocious: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Music: out

Kousha Navidar: This is Climate One. I’m Kousha Navidar. Our next guest has spent many years thinking about ethics, values, and spirituality in the context of environmental governance.

Iyad Abumoghli is the founder and former director of the Faith for Earth Coalition of the United Nations Environment Programme. He’s also founder and chair of Al-Mizan, an Islamic approach to protecting the environment and addressing climate change.

Iyad Abumoghli: Sustainable development is economy, social development, and the environment. However, what is missing is the cultural component. And the cultural component includes practices, includes religions, includes ethics and values. And that is important because what determines the behavior of people is their culture, is the upbringing, is their, their beliefs and their ethical values. You know, 85% of the global population believes in a faith or a religion and those have established centuries-old doctrines that inform them how to speak, how to talk, how to walk, how to dress, how to eat, and in all of that is related to sustainability and living in harmony with nature.

Kousha Navidar: So is it like the framework that you're talking about here, like faith can succeed at putting action into frameworks that have lineage and moral understanding? That's what I'm hearing from you.

Iyad Abumoghli: Right, the moral understanding and the spiritual driving force behind the behavior of the people, whether they are individuals in their homes, in their cars, and so on. Or spiritual people who run businesses, you know, people, CEOs of, of any company. They go to mosques on Fridays or Sundays, if they are Christians and, and so on. So their behavior is actually driven by their spiritual belief.

Kousha Navidar: So it kind of sounds like what you're saying is that politics and policy can say the what, but religion can maybe say the why.

Iyad Abumoghli: Exactly. And not only why in terms of how it is related to human activities and nature, but why are we doing good? Why do we have to protect nature, not all our own surrounding, but the surrounding of others and other continents, so we have a moral obligation towards humanity. It's a spiritual obligation that we are all in this together. The main concept of Laudato Si’ to see is interconnectedness between people and between people and the planet.

Kousha Navidar: So let's talk about that interconnectedness a little bit further. Cause I think that's very well said. A few years after Laudato Si’ you founded Al-Mizan, which means “balance” in Arabic and, and I used to be a speech writer. I love etymology even when it's words outside of English. And balance is such a beautiful phrase there. Al-Mizan applies principles from the Quran to meeting current challenges. Tell me how Al-Mizan came to be.

Iyad Abumoghli: Well. Definitely, I would say immediately it was inspired by Laudato Si’ and when I saw that, you know, 2.2 billion people believe in Christianity and they have something that is taken from their belief and, and their basic teaching. And I said, there's also 1.9 billion Muslims around the world. They have one book that they are referred to for their daily lives, but also for their businesses. So the Quran is also a resource for environmental governance. So many verses in the Quran speak about specifically how do you deal with water resources, uh, practices of Prophet Muhammad, peace upon him, specifically talk about how people should not waste. And in the Quran says, God does not like wasters.

Kousha Navidar: Mm-hmm.

Iyad Abumoghli: So Al-Mizan is a general concept in the Holy Quran that God has created everything in balance. Everything was created in pairs, in perfect shape. It talks about, you know, the skies and the earth, talks about the sun and the moon, and, and they cannot, but by God's will, change their courses and and so on. So who are we as humans to play with that and change the course of things that got created. Al-Mizan contains also 50 other principles taken from the Holy Quran that relates to environmental sustainability and our relationship with nature. For example, justice talks about, you know, al Justice is something that drives human behavior between people and with their surroundings. It talks about compassion. If God is compassionate, why can't we be compassionate to others and to nature. It talks about, ilfiltra, which is how God created us, loving nature and living in balance with nature. So if we do, live how God created us, then we do not unbalance anything that we have. So we took the global challenges that we are facing, and we related each one of them to, you know, what the Quran is saying, climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, even economic systems that we have currently. And we related that to the economic system that was created in Islam, using the words of God.

Kousha Navidar: Justice, compassion. These are complicated, heavy concepts. And to find a framework that applies it to climate sounds so valuable. How is the Faith for Earth Coalition using Al-Mizan as a framework for engaging Muslim communities on climate action?

Iyad Abumoghli: Well, we are using both Laudato Si’ and Al-Mizan because, you know, Faith for Earth is an interfaith initiative. We do not promote one religion over the other. Uh, we then we work with Hindus with. Buddhists with these artists, with all types of religions. However, as I said, those two religions are the most established in terms of having something concrete. One specific document that we refer to. Judaism is the same. Right. So we do work with Jews as well but Muslims and Christians constitute more than 55% of the global population. So it's a great golden opportunity to work with both communities. So we have translated Al-Mizan into 11 languages, so we wanted to reach as many people as we can. And then we are trying to push the implementation of the principles mentioned in Al-Mizan on the ground. For example, the establishment of Al-Mizan Park in Jordan, which uses a concept called al-hema, which is protected area that was established 1400 years ago. And it details how people should plant trees, how they should do hunting, in specific seasons with specific amounts for specific reasons. So it's a whole complete system. We are also using the ecotourism concepts of Al-Mizan in Tanzania. You know, to prevent overextraction of resources. So there are many on the ground actions that have been adopted and implemented by a number of countries.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, you mentioned that if you put Islam and Christianity together, it represents more than half of the world's population, right? So.

Iyad Abumoghli: True.

Kousha Navidar: In my mind that made me also think they must own a lot of assets as well, including land. So what are they doing to leverage these assets for environmental benefit? And, and maybe even after that, what should they be doing?

Iyad Abumoghli: Right. And, this is one of the main goals for the establishment of the Faith for Earth Coalition within UNEP. We looked at the wealth. Let me put it this way of, faith organizations. And it is found to be the fourth largest economic power on earth, and they own 8% of habitable land on earth. If you want to imagine that, imagine the size of the United Kingdom. What faith organization owns is 36 times the size of the United Kingdom. So this is humongous. They own more than 5% of commercial forests at the global level. So one of the main objectives was to work with these organizations to green their investments and assets. First of all, most of the religions have principles for financial transactions and investments. For example, Christianity and Islam, and, you know, Hinduism, they don't allow investment in alcohol production. Okay, this is a no no. Uh, they don't allow investment in arms industry. But we did not find, except probably in Islam because it's more advanced in its financial system, principles for green investments, right? So we have worked with many financial organizations and many faith organizations to first of all launch a divestment movement. So we divest from investing in fossil fuel. But then again, after that, where do you invest? If you divest, you need to put your resources somewhere. So, of course, with the science and, and economists and so on, we are finding that green economy is the alternative so we move to green economy. It's more profitable to the people and the planet.

Kousha Navidar: Are you saying that religious institutions should be doing more of that? More of that transferring of assets to the green economy?

Iyad Abumoghli: Definitely, as investments first, but also as greening their own assessment. Look, there are estimates of, more than 4 million mosques, more than you know, a hundred million temples across the globe. These are buildings, and we know the building sector contributes to climate change.

Kousha Navidar: That's a great point.

Iyad Abumoghli: because it produces carbon, it uses water, you know, uses electricity and, and so on and so forth. So if you green your house of worship by installing solar system, reducing water consumption, planting trees that are around it, using, you know, the spaces for organic farming and so on, then you are contributing to reducing climate impact.

Kousha Navidar: You are encouraging Al-Mizan to use the phrase that I learned before this, before this interview. At last year's UN Climate Change Conference, the president of the host country, Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliev praised oil and gas as gifts from God. What was your reaction when you heard that?

Iyad Abumoghli: Well it is a gift from God. Everything that God has created, created for a reason, and everything is, is a gift. But of course, gifts cannot be abused and cannot be overused. Water is a gift of God. But if you consume more than what you need, then you deplete water resources and then there's nothing to drink or run your industry or plant your trees. So everything has a limit. Now, I believe over the past 200, 300 years we used it. We produced development, we advanced nations, but it's about time that we understand that we have used it more than we needed because, you know, nature has a natural way of getting rid of pollutants, right? This is the Al-Mizan, the balance that God created. If there is carbon dioxide, there are forests, oceans that absorb carbon dioxide. But if you start producing more carbon dioxide than the capacity of earth, then you need to understand that God did not allow you to use that gift to that extent. Right. So now it's about time that God also provided technology that we can use sun, water, whatever other natural resources to produce energy without contributing to depleting the natural resources nor polluting our environment.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. So for you, for you, it, it's not so much the, the phrase it being gifts from God. You totally agree. It's what we do with those gifts that you feel. Yeah. So, so there's, there's something that you experienced recently that I was very excited to ask you about, and I saved it for the end of the interview. You recently met with Pope Leo, King Charles, Prince Hasan and the president of Lebanon and, and, and other, several other faith leaders in several conversations centered on the role of faith and values in facing our most pressing challenges of climate change and climate justice. Those are, those are big meetings that you had. I'm interested. What was, was there anything surprising or gratifying that came out from those talks with you?

Iyad Abumoghli: Definitely. Well, first of all, having a global political figure talk about not only environmental issues, but about ethical issues is heart-warming. Right. So that means at the top, there are people who care about the environment, about its people, about, you know, how we run economy and so on. So these conversations, discussed how can we maximize the efforts of the people to push forward what we all believe, but all, you know, politicians try to shy away from. So Pope Leo for example, the meeting with him was heartwarming because he re-iterated his support to Laudato Si’. We thought, you know, new Pope, new policy, new direction. But no, he came and said, whatever Laudato Si’, I am behind it a hundred percent and we need to do more. King Charles, I mean, he reiterated the common values between religions. When we talked about Al-Mizan and Laudauto Si’ he immediately said, well, there are so many common things that can bring people together for, you know, an ethical approach to the issues that we are dealing with.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. So for you it was very gratifying to feel like the momentum is continuing right, picking up the mantle going forward. Global religious leaders have been pushing for climate action at least since Pope Francis 10 years ago. So what can be done to get political leaders to listen to moral leaders?

Iyad Abumoghli: We need to do more within the realm of religious leaders. We wait unfortunately until COPs organize a faith leader summit. And we issue a beautiful declaration, that sets out common values and you know, what we ask of member states and, and what we commit to do, but that is a moment in the history of things. What we need is a constant continuous engagement with the decision makers and political leaders. Right. So we don't leave it for a COP to happen and then we engage. We need to work at all levels, not only the high level, but also the community level. You know, faith leaders can impact the electoral choices of people. Right. Don't elect for a decision making post or, you know, a mayor or a parliamentarian if they don't uphold ethical approaches to the relationship between people and the relationship between people and nature. So it's a whole system that we need to create and move forward with a system that works on a daily basis, not only on occasion.

Kousha Navidar: Iyad Abumoghli is founder and former director of the Faith for Earth Coalition at the United Nations Environment Program and founder and chair of Al-Mizan. Iyad, thank you so much for joining us and for all of your work.

Iyad Abumoghli: Thank you very much for giving me this opportunity. It was a pleasure talking to you.

Music: In

Kousha Navidar: Hey everyone, it's Kousha and Ariana. It's the end of our show, which means it's time for climate one more thing, I'll start. Uh, Ariana, have you gone on Zillow like every other millennial and me?

Ariana Brocious: Only just a few million times?

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. Yeah, you get it. So Zillow is the world's largest like platform for buying and selling homes online. And you know, Ariana, that at the bottom of most listings, they have a climate risk score that shows the likelihood that this home you may wanna buy, uh, could experience a flood or a wildfire. Get this, they're no longer showing those climate risk scores.

Ariana Brocious: What, why?

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. Well, okay, so I read this in the New York Times, uh, Zillow's removing those scores because representatives of the real estate industry and sellers of homes, like private sellers are saying that the scores might not be as accurate as what is uh, a hundred percent verifiable and that it might be hurting home sales. They're basically saying it's not required. Why put it up there? The company that provides those scores, First Street, which we've had on the show, says they're very transparent with where that has come from. They're verified by multiple independent groups, even if they're not a hundred percent predictive. So I think it brings into question this weird tension between capitalism and what's good for the environment, frankly, because some folks are saying, we don't wanna hurt home sales. And other folks are saying, we wanna know if this home is gonna experience a flood. So I thought it was a pretty interesting focal point of, of, uh, the state our society is in.

Ariana Brocious: Well, no kidding. I mean, there's a lot of information that's associated with a home listing that's not required that gives you a sense of what kind of neighborhood you're gonna be buying into. But also, as we've talked about repeatedly on the show, this is real risk that people are encountering. And your home is often your largest financial asset. So you should know if you're gonna be buying in a wildfire zone or a flood zone. You know, this is kind of essential information. So, okay, more to, more to learn there.

Kousha Navidar: Uh. Yeah, and there's some nuance to it, so be sure that you check it out. You know, these scores predict years into the future, so there is something to be said for how accurate they are in every single listing, but yeah, like what is the real objective here? Uh, Ariana, what do you got?

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, so mine's a little more uplifting. I was in Salt Lake City a few weeks ago and I was at the Natural History Museum and found this really great interactive climate exhibit, and it kind of surprised me because I feel like that's the thing I don't see that often out in the world, and it was very up to date. It had quotes and testimony from people we've had on the show before, like Katherine Hayhoe and Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, and it even had this interactive screen where you could find your climate action through this sort of climate venn diagram that I've talked about with Ayana Elizabeth Johnson. So it's kinda like what you're good at, what you like to do and like what's useful. And then there was also this very interesting exhibit that was about emotions and feelings around climate. And you had to, oh, select an emotion and then this digital display of aspen trees would react to your emotion by changing color or shifting in the light. And it was a really interesting set of exhibits. So I was excited. I thought it was cool to see that, uh, as I said, in the real world and um, you know, right alongside all the cool dinosaur skeletons and, and other things they had there.

Kousha Navidar: I love dinosaur skeletons. I feel like there's a fossil fuel joke in there, but I'm not clever enough to figure it out. What, uh, do they talk about solutions though?

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, yeah. There was this whole section on what Utah itself is doing, including exploring technologies like geothermal, which we've, we've talked about on the show. Um, there's some really exciting stuff there and, you know, things that are present lots of places like wind and solar and other technologies. So. Yeah.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. Shout out to Utah. And that’s our show. Thanks for listening. You can see what our team is reading by subscribing to our newsletter – sign up at climate one dot org.

Ariana Brocious: Climate One is a production of the Commonwealth Club. Our team includes Greg Dalton, Brad Marshland, Jenny Park, Austin Colón, Megan Biscieglia, Kousha Navidar and Rachael Lacey. Our theme music is by George Young. I’m Ariana Brocious.

Music: Out