Gloria Walton and Wawa Gatheru Believe in Grassroots Change, Not Just Charity

Guests

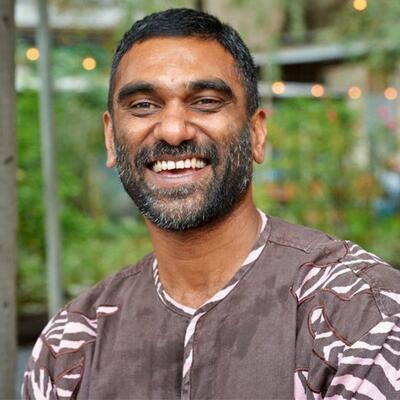

Gloria Walton

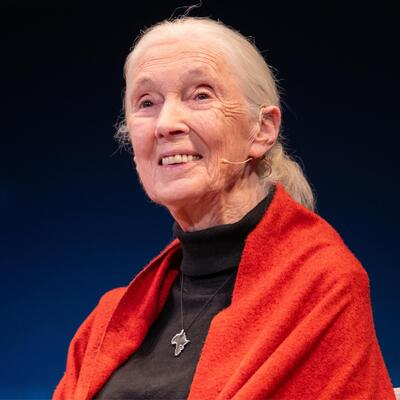

Wawa Gatheru

Summary

Those standing up to climate and environmental injustice face challenges they weren’t seeing a year ago. But Gloria Walton, president and CEO of The Solutions Project, sees a bigger picture:

“ The reality is that the same systems that created the climate crisis, whether that's colonialism, white supremacy, racism, and the patriarchy, those are the same ones that have harmed communities of color for generations,” she says.

The Solutions Project has channeled tens of millions of philanthropic dollars to grassroots efforts that build community resilience. Walton says the organizations that The Solutions Project supports recognize the core idea that people are more resilient together.

“We are not in this alone, right? And you know, abundance is knowing that you have neighbors and an entire community that can show up for each other and look out for each other.”

She spent years working as an economic justice organizer in South Central Los Angeles, and says as she began to explore and understand climate change, she saw that justice was about more than jobs and the economy. “This is about air quality, clean water, the energy transition away from fossil fuels to renewables and solar energy. It's about transportation, food, justice, equitable resources and access to those resources. And that's when I realized that, okay, climate justice is what's interwoven into all facets of society and the systems in which we live.”

When Wawa Gatheru started attending climate and environmental meetings, she didn’t see many people that looked like her. So she set out to change that. She founded Black Girl Environmentalist, a national organization that helps more Black girls, women, and gender-expansive people enter and lead in the climate space.

She’s also focused on shifting the narratives around climate disruption and the role of some of the most impacted communities.

“Social media really rewards fast, simplified narratives that oftentimes fall into misinformation and voyeurism, especially when it comes to telling stories of climate disaster, and maybe sometimes sidelines the climate resilience and even climate joy that can exist when you get involved,” she says. “Whereas climate storytelling always must lead with truth and nuance, and sometimes the two can feel at odds. But I'm a firm believer that you can do both at the same time. It just, again, requires intention and requires the communities themselves to be in the front seat.”

Resources From This Episode (2)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Ariana Brocious: Kousha, how long have you been an interview host?

Kousha Navidar: Um, my first hosting job was in 2016 on PBS, but I was just not just, I was reading scripts into a camera and I think my first interview was when I was in seventh grade and there was a day long like. Choose your own adventure workshops for everybody to like learn about jobs and whatever And I didn't want–

Ariana Brocious: Like a career day?

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. Or like, here are skills that you can learn in half an hour sessions. And I didn't wanna do any of 'em. I just wanna walk around and talk to other people about. What they thought about the sessions. And one of the teachers suggested that I do this instead. And at the time I was like, I'm special. That's right. I'll do this. But I think in retrospect they're like, oh, this seems to be what he's interested in. We can like, which is like great teaching. Um, so it's been a while for me. How about you?

Ariana Brocious: That is a while. Um, so I was the local host of Morning Edition for the Nebraska Public Radio Station for a few years, and that was, you know, a great experience. Lots of on-air time, but then. I didn't really do much interviewing to be heard on air until later. I did a lot of interviewing as a reporter where I would talk to people, but usually my voice didn't end up on the tape. Uh, I don't think it's really until a couple years ago, a few years before this job that I began to do more interviewing.

Kousha Navidar: Hmm. What do you like about it?

Ariana Brocious: Oh, I like talking to people. I always have. Um, and I like learning how people view the world and what they think you know, about whatever issues we're discussing, obviously, but. I think when done well, it's a way to just get to know somebody and, um, it's a nice human experience. I don't know. What about you?

Kousha Navidar: It is a total human experience, right? Like, I feel like the thing that, uh. So many of us have in common despite like whatever our job is or whatever our background is, is that we all wanna be understood. And I think that when you listen really intently and you hear what somebody's offering, it can be a very meaningful shared human experience. And that's one thing that I like. I also like the performance art aspect of it, which I feel like you will not be surprised about at all. But there is drama in people's stories. There is the flow of a conversation. There is an art form and a sport to it actually of, of listening and engaging.

So those are some of the things I like about, and I like learning new stuff, right? Like when I was a speech writer, I was interviewing people. All the time. And then I was just kind of writing down what I heard and adding like the, like weaving the plot together. And it was so wonderful to hear it on the other side. Like you were just learn, becoming an expert in something for like a few weeks. From experts. So that's what I really like about it and I think that reminds me of this. Episode especially because I got to talk to, and it sounds you as well, got to talk to, uh, individuals that had really wonderful stories to share and uh, it was really cool to hear it on the, on the other end 'cause I felt like I was in a, a very meaningful conversation.

Ariana Brocious: Likewise, so let’s get into it. I’m Ariana Brocious.

Kousha Navidar: I’m Kousha Navidar.

Ariana Brocious: And this is Climate One.

[music change]

Kousha Navidar: You know, Ariana, this episode feels special to me. I really enjoyed the conversations.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, I agree.

Kousha Navidar: I had the opportunity to talk with Gloria Walton, president and CEO of the Solutions Project. She’s channeled tens of millions into grassroots efforts building resilience.

Ariana Brocious: I talked with Wawa Gatheru, founder and executive director of Black Girl Environmentalist, who’s working to create much more inclusive climate spaces and advocate for a more complete picture of the climate narrative.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, that complete picture theme ran through both conversations. For me it was very invigorating because some of the themes that came up were how you bridge grassroots to philanthropy. And what does grassroots really look like today?

Ariana Brocious: Both of these women are focused on local solutions, and people on the ground. And they know that people closest to the issues often know how to solve it, sometimes they just need resources.

Kousha Navidar: Both have strong interest in shifting the narrative from victimized frontline communities to people with agency who are solving their own problems – even ones they didn’t create.

Ariana Brocious: And these solutions can be really impactful. A July report prepared for the MacArthur Foundation and some others that documents how community-based climate strategies can achieve measurable greenhouse gas reductions. AND they can build lasting community engagement.

Kousha Navidar: Those are the kinds of efforts supported by Gloria Walton at the Solutions Project. Let’s jump into my interview with her.

Kousha Navidar: I wanna start by like acknowledging the moment that we're in, because a lot of people are standing up to climate and environmental injustice and they're facing challenges that we weren't seeing a year ago. So how are you processing what feels to me like both a political and a cultural change?

Gloria Walton: Ooh. Um. You know, my year started with the Altadena fires. And Altadena was my home. Like that's actually where I lived and where I bought my first home, which is like this historically Black community. and you know, experiencing the fires there just hit like in a way that I, you just can't even be prepared for. Like my heart dropped the minute that my former neighbors called me the night that their homes started burning. You know, and that just kind of gives you a sense of how close we were and how the community is like for me to have moved and my neighbors are calling me the night that the fires hit our home is a big deal. And thinking about today and how they’re still impacted because it was kind of like headline news at the top of the year. And then fast forward to today, you know, now we have different fires, but those communities are still in recovery. Many displaced, dealing with like the effects of what happens when communities end up being hit by a climate crisis where you have people from outside the community looking at this land and really seeing an opportunity to kind of swoop in and leverage the disaster to further privatize like the land and the water and accumulate more capital and displace those communities that live there. And all in all those communities are coming together so that they can actually put forward a strategy so that they can remain in their community.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. So even with changes happening one way or another, the tragedy is like being felt very close to home for you no matter what.

Gloria Walton: I mean completely, like the empathy just runs deep because it literally could have been me and in and in a lot of respects it feels like it was because it affected and impacted people that I deeply care about. You know, these are some of the best neighbors that I've ever had. And the fires is just like, you know, when you think about this political moment, that was just the top of the year. You know, since then, it's like we've had severe rollbacks to DEI, you know, climate policies, the gutting of FEMA and NOAA, right? These are supposedly the first government responders when disasters hit NOAA being like a federal agency that works to understand weather and predict weather and climate. You know, I think about communities that we serve, like the immigrant communities that are being targeted right now with the ICE raids. And that's happening in California and all over the country where it's like job sites, you know, they're targeting schools, hospitals, parks, and other ostensibly safe spaces. And then you think about like the legal, digital, and physical threats that are happening right now to a lot of communities and the surveillance and the harassment. We know that there's been like so many federal cuts that have also impacted a lot of the groups and organizations that we support as well as local communities.

Kousha Navidar: Before we move on, I mean, I'm interested in how your former neighbors are doing.

Gloria Walton: Yeah, so I appreciate that. You know, they're still struggling. A lot of people have been displaced and they're staying with family. And for those who haven't been displaced, You know, they're also still in their homes and they're now dealing with the public health implications of fire. And we were able to, The Solutions Project, connect the families there with this company and organization called Aclima. And essentially they do air quality and water, quality monitoring, and we connected them to the local community and they went and they tested the soil and the ground and the homes, and there's basically high amounts of benzene and lead, right? And so these have really serious health implications. And so families are dealing with the public health consequences while like meeting with each other and trying to have a vision. For how to rebuild that actually keeps the people there, versus displacing them and moving them out and letting developers, and other folks with capital kind of swoop in and, and seize this moment.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, so now we're getting into some of the work that you do at the Solutions Project and, and I think a lot of it is rooted in, in your own experience too. So before we dive deep into the work now, I think it might help to think about you, Gloria, and what you brought to the table. I mean, before you started what is now a multimillion dollar organization, you worked for 16 years as a community organizer in South Central LA. So what did that experience teach you?

Gloria Walton: So much. My time at Scope, Strategic Concepts and Organizing and Policy Education, which was my former organization, really set important and critical foundation in my life and for my work. I always say that being born Black in the US and around the world is intrinsically political. But being at an organization like Scope actually took that political awareness and my political analysis and my political experience to a completely different level. You know, I was in college when I started there, and so I did community organizing and learned from some great organizers and leaders to this day. Anthony Thigpen, Mayor Bass, the mayor of Los Angeles. You know, she's a former community organizer in South Central, right? So I had the privilege and the honor of learning from them. And what was great about organizing is that it helped me understand. And situate my personal experience and my family's experience in a broader context. And it helped me think about the systems that are at play that created a lot of the conditions that we lived in and how we grew up, like the problems in those conditions that we lived in.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. You know, when we spoke earlier, you told me that you grew up in poverty, and yet you also had a sense of abundance, I think is the word that you used. How do you simultaneously hold a sense of scarcity and abundance?

Gloria Walton: Yeah, so you know, growing up in poverty, I was partially raised in Jackson, Mississippi, but also parts of Northern California. And my mom and my grandmother raised me and we were conservationists out of necessity and what that means is that we thrifted, we reused everything. We like conserved energy, right? Like if you're not in a room, you turn off the lights. If you're, like, when you're brushing your teeth, you don't just let the water run while you're like brushing the whole time, right? Like,

Kousha Navidar: We grew up in very similar households. Yeah. Every light.

Gloria Walton: – because they're paying those bills, right? So, you know, and that's kind of like that conservationist attitude. And we did that in a sustainability attitude really. But it was rooted in survival, right? Because it's like if you already don't have much, like, you're gonna be mindful of like how much energy you're using how much water you're using. That's one serious reality.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, that's the scarcity side.

Gloria Walton: But the other –

Kousha Navidar: Tell me about the abundance side.

Gloria Walton: That's the scarcity side, right? That many are familiar with, too many really, but the abundance side, which I think so much about, and a lot of the organizations that we support at the Solutions Project is very central to the work, is recognizing that we are not in this alone. Right? And you know, abundance is knowing that you have neighbors and an entire community that can show up for each other and look out for each other. So when my grandmother went to the grocery store 'cause she had a vehicle, but our neighbor across the street didn't, she would let her know, right? And she would say, Hey, I'm gonna be going to the grocery store on Monday. Do you wanna join me? And we would carpool together, if someone needed certain resources to kind of know how to save money on this particular bill or where you go to get this particular resource. It's like people talk to each other, you know, neighbors, just like we knew each other's names. Everyone on the block knew me.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, you weren't on your own.

Gloria Walton: Exactly. You're not on your own. And there's an abundance in that. Right? It's recognizing how much more you can have when you share and pool your resources. Right. And it's not just thinking about the little bit that you have, but like, what do we have together?

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, which kind of lies at the heart of what the Solutions Project does a lot. It's finding the communities to help support the projects that you find, which makes total sense. And one more question that I had about your experience as a community organizer is you, you talked about it helping you put into a systems context what you, yourself, Gloria, experienced.

Gloria Walton: Absolutely.

Kousha Navidar: Can you think of a specific example where that systems level thinking, where that just like context filled in for you?

Gloria Walton: Yeah, so you know, when I started in organizing, I was actually an economic justice organizer and I was often thinking about the economy, and I felt like that was the space that held all of our interlocking systems. And to some degree, it, it really, it does right? Like it, it holds so much. And my entree point into climate was actually researching the economy and jobs and like thinking about, okay, what's gonna be the next big growth sector? And this was way back in like 2006 or something like that, 2005. And I started researching what investments were going to be coming down to create jobs and how to make sure that black and brown communities could have access to those jobs. And it was actually climate at that time where I saw and found that it was gonna be trillions of dollars that were going to be invested in this new industry, and that it was gonna be an opportunity to have like a career ladder, an entree point for new folks, but then also a career lattice if you're thinking about, already existing jobs that will be, you know, transformed to cleaner jobs. Right? And, and thinking about how to move from a dirty job to a clean job. And then the more that I delved into climate, I really saw how, okay, this is more than about jobs in the economy. This is about air quality, clean water, the energy transition away from fossil fuels to renewables and solar energy. It's about transportation, food, justice, equitable resources and access to those resources. And that's when I realized that, okay, climate justice is what's interwoven into all facets of society and the systems in which we live. And the reason it became bigger than the economy to me is because climate justice is not just about the economy. It's about people, and it's about our land and our resources and how we interrelate to each other. Right? And that's like the real all encapsulating issue of our time.

Kousha Navidar: I'm really interested in the fact that you brought up people as a part of that, because like this is kind of bringing us to the present now with the Solutions Project. A key tenant of your organization is that the solutions to the climate crisis exist within frontline communities, exist with the people. Right. How did you come to that realization?

Gloria Walton: Organizing. In South LA we were a community that was defined by the freeways that surrounded us.

Kousha Navidar: Mm-hmm.

Gloria Walton: It was called South Central because there was a freeway to the north, the south, the east and the west. And we, our community was at the center of all of that. Plus we had the ports that were in Los Angeles. So you know that there's diesel trucks coming through our communities. On all the freeways that surround our communities. So we actually had some of the poorest air quality in LA County which meant that we were some of the sickest communities, the highest rates of cancer and other illness, the highest mortality rates compared to other places in the county. And this wasn't happenstance, right? Like there are decisions that are being made every single day that create those conditions that we're living in. And. Once I realized that, that I learned that from the communities that had already been doing this work, like I was able to join a legacy of organizers who've been doing this since before I was born.

And I had the honor and the privilege to learn so much from them. And when you kind of narrow it down to the fact that there's people sitting in a room making decisions about your life and my life. And either you can be on the side reaping the consequences of that, or you can actually go in that room, and share your perspective, your voice, and your analysis and your solutions and, and have a seat at the table. Just knowing that it's that easy, like to make that phone call, to do that delegation to an elected official, it's that easy to help shape your democracy, to shape your community, to influence the real conditions that you and your family are living with.

Kousha Navidar: Well, when you say easy, what do you mean by that? Because I imagine some people will be listening be like, easy, I don't know.

Gloria Walton: It’s not easy, huh? Right. What I mean by easy is that our democracy is about your power and my power. Our democracy is about community power, and too often I think it's easy, like a dominant theory of change that we all rely on or defer to is that you just put someone in office and you know, supposedly they align with your values and what you believe in, right? At least that's what you surmise and, and you just kind of leave the decision making up to them. But the power in our democracy is actually saying, okay, yes, I'm going to try to elect someone who I think aligns with, uh, my best interests. But I can't stop there because the magic and the power comes with me holding them accountable to my vision and my interests. And that's through voting. That's through making phone calls, that's through lobbying. And you don't have to do these things alone, right? You can link up with your neighbors, you can link up with community organizations to make this happen. But there's a lot of avenues if we look for them to be an agent of change, right? And not just like on the sidelines, reaping the consequences of other people's decision.

Ariana Brocious Coming up, Gloria Walton shares her vision of philanthropy:

Gloria Walton: It's about change, not charity, right? Like it's about solidarity and showing up for the people and the communities and the places that we love.

Ariana Brocious: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Kousha Navidar: This is Climate One. I’m Kousha Navidar. Let’s return to my conversation with Gloria Walton, president and CEO of the Solutions Project. One of the initiatives her organization supports is the West Street Recovery Project in Houston, Texas, a state that recently experienced deadly climate-driven flooding.

Gloria Walton: West Street Recovery emerged in response to Hurricane Harvey, and we know at least now from like looking at the media that there's like repeated floods. And communities basically have to take their lives into their own hands. And West Street Recovery has been like fighting for these communities and really trying to rebuild this neglected infrastructure in their community. And one thing that I wanna mention is that they recently won $ 20 million for like drainage investment and reversing a 22-year-long city ordinance that basically led to unequal infrastructure in communities of color.

And all this happened because of the grassroots organizing that they were doing that advocacy. and it was all around improving outdated drainage systems given that they had so much flooding there. The drainage system is so important to make sure that it's actually up to date. And so when they passed this $20 million victory, it basically increased the local drainage program and the city started to respond and address a lot of these neglected areas.

Kousha Navidar: So how does a project like that, exemplify your personal mission?

Gloria Walton: West Street Recovery, it's grassroots. It's about the community. It's led by, driven by the people most impacted by the problems and conditions. And a lot of the organizations that we support at the Solutions Project are grassroots organizations. So they're local. One of the things that West Street Recovery is doing that a lot of our partners are actually doing, is building resilience hubs. Have you heard that term?

Kousha Navidar: No. No. What? Yeah. I was about to ask what is that?

Gloria Walton: So resilience hubs, basically it's like a collective response, at the local level where you have community, local organizations and businesses working together as first responders, boots on the ground, offering mutual aid to each other and mapping community assets and resources.

Kousha Navidar: Well, like can you gimme an example of a community asset, like a shelter in place, location, or like, or what? Yeah.

Gloria Walton: Yeah. So like if a disaster hits, and in Texas they're dealing with winter storms, severe heat waves, a hurricane, right? And so if the community facing any of those and a power outage happens, for example, they've actually mapped who on the block or in the neighborhood is the home that has backup solar panels and batteries.

Kousha Navidar: Oh wow.

Gloria Walton: Who's the point of contact, who's gonna reach out to the local community who can provide food and water to the community when there's an outage? Because those things end up being a matter of life and death when crisis hits.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. A quote that I've heard you say before is, our communities are too often depicted as victims when in fact we are victors, and there's a lot to unpack there. So first, why do you think frontline communities are portrayed as victims?

Gloria Walton: Often our stories are told by someone else. Right now we're constantly inundated with misinformation, lies, climate denial, and so many counter narratives that push against us and try to hide the political will that is at play and telling us that we're powerless, right? Which is another lie and climate change, deniers are using their power to gaslight us all right? Now, you know, up is literally down on every issue, whether that's democracy, climate change, reproductive rights, family values, equity, diversity, you name it, right? And they're using the news and social media to misinform and malign and to invoke fear and overwhelm and to spread hate.

And so they've taken the very narratives that we've created and they have appropriated, undermined and villainized them because they know that stories are powerful. And so the Solutions Project, we support communities and grassroots movements taking their power and their stories back. And that's literally shifting away from victims to victors and visionaries and rewriting the narratives from disempowerment to self-determination, you know, and taking control of our stories and showing that solutions don't just come from like the top down, but they actually come from the ground up.

Kousha Navidar: Mm. At the same time. I hear in so many circles I hear about people of color, you know, here in the US or, or residents of developing countries, low lying island nations, they are affected by climate disruption first and worst, right? Like those who contribute least to the climate injustice in the world are also experiencing the greatest floods, the greatest fires, et cetera. Is that not true? I mean, if people are being hurt by a problem that they didn't cause isn't that the definition of victim?

Gloria Walton: Yeah, so if they're being hurt by a problem that they didn't cause. Absolutely one part of the story can be victimization, but the story shouldn't stop there. And often the story stops there. And so when people think about these communities, that's what they think about. Oh, victims, those poor communities, the people who are impacted by that thing over there, it's not going to impact me. But when communities tell their own stories, they can talk about the problems, right? Because I think that that's. Important. And it's, it's like a way that people understand the impact of things, but they can also talk about the solution and they can talk about how they overcome those problems. They can talk about their vision, they can talk about the power that they're building. They can talk about who they're an allyship with. So it just creates a more expansive story so that people can actually see themselves in it and know that when disasters hit, it doesn't just begin and end with victimization.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. In your mind it is the, the, the 360 view of a person who is experiencing a hand dealt that is quite difficult but it is. One piece of that story is what I hear you saying, which is crucial. Yeah. You know, one root of injustice is the unequal distribution of money, and you're now deeply embedded in the world of philanthropy and you're channeling tens of millions of dollars into frontline communities. And yet that's still a drop in the bucket, right? Like it's been reported that of all the philanthropic dollars that are out there in the world, less than 2% is devoted to climate. And of that, how much of that flows to frontline community organizations? Do you have a sense of that?

Gloria Walton: A fraction, right? If it's already less than 2%, a fraction of that flows to those who are most impacted.

Kousha Navidar: So for you, I mean, the position that you are in, I find so fascinating because you are looking at what is oftentimes like the lifeblood of change. On one hand, like money, money makes a huge difference. Money can solve problems, money can move mountains. How can you change how and where philanthropy dollars flow?

Gloria Walton: Yeah, so you know, philanthropy. Is actually a Greek word. You know, before I chose to be in philanthropy, coming out of organizing, and I still identify as an organizer even though I'm in philanthropy. And that's really important because it's. Giving you a sense of my purview and who I'm accountable to, which is always the ground and communities, and who I'm actually in this work for, which are local communities. And so when I think about the Greek word, um, once I look this up, it's philanthropic and it actually means for the love of humanity.

Kousha Navidar: I love that. I love that.

Gloria Walton: Me too.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. I love that.

Gloria Walton: So, when I learned that, I was like, of course this is what I would be doing. Like, you know, it's about change, not charity, right? Like it's about solidarity and showing up for the people and the communities and the places that we love. And then the more that I experienced philanthropy, when I ran an organization on the ground, SCOPE, it was clear how hard it was actually to get resources to communities that are most impacted by the problems and conditions. And then being in philanthropy, I learned exactly that stat that you just talked about with the less than 2% going to the communities that are disproportionately impacted by problems and conditions. And so when you look at the flow of capital and philanthropy 'cause that's the, the main resource that's moving around. It was actually flowing to well-resourced, predominantly white-led larger organizations and institutions, and the least amount of resources were actually flowing to the communities most in need. And not from just a victim sense, right? Because the community is most in need or actually advancing solutions in real time. They're not just saturated in victimization. They're trying to create change right now. And that's where the least amount of resources was going. And that's the sweet spot for the Solutions Project is actually,stepping into that gap and painting a picture of like, if this is about the love of humanity, we are not meeting the mark, right? And it's having that larger conversation with philanthropy. I have to fundraise, right? Like, you know, we all fundraise at The Solutions Project because we raise this money to move to communities that are on the front lines.

Kousha Navidar: You know, you've been recognized for, quote, wrangling $43 million from Jeff Bezos. And you got that for climate work, climate justice work, how do you navigate relationships with major philanthropists while maintaining grassroots authenticity?

Gloria Walton: I actually helped to raise about $151 million for the movement and part of that is also thinking about accountability, because as great as it was to raise that kind of capital, you know, we started off with a small amount that was offered to us and I amplify that up more than, like 10 times the amount that was offered to us. Basically it was like a 2 million dollar conversation transformed to $151 million conversation that supported many organizations. And I didn't stop there. I didn't immediately say yes to that. I actually was grateful and I thanked them for listening to us for those couple of months and, and heeding our call and our request to some degree.

But I also made sure that they were clear that we are accountable to the movements, and that I needed to talk to those folks. And so I personally, before accepting those resources on behalf of movement. And again, a good amount of those resources were going to organizations directly, not just through the solutions project, but I personally talked to about 33 labor leaders across the country, and this was important given.

You know, Amazon's a big company. Jeff Bezos is a world renowned name that many know, and there's a lot of controversy around both of those things, whether it's him or his company. And that's not to knock the great people that are working at Amazon and, and doing good work. 'cause you know, obviously that's part of the story too. But given the controversy, I knew that it was important to personally talk to those labor leaders and share the story and share how we started,what the original offer was, what we were able to transform the offer into and get their blessing, to receive those monies and move it to the communities that are most impacted.

Kousha Navidar: So you –

Gloria Walton: And hands down,

Kousha Navidar: You got their blessing before you accepted.

Gloria Walton: Hands down, all of them said, you know, Gloria, this, you know, many, many folks get a little bit of money like $200,000 and don't have these conversations with each other. And the fact that you have $151 million on the table and you're calling us personally, to have this conversation means everything. And so if we trust any organization with these resources, we trust you and the organizations that you all are representing.

Kousha Navidar: How do you maintain that momentum that you're talking about when facing both climate urgency and systemic inequities?

Gloria Walton: Oh. What comes to mind is. The reality that the same systems that created the climate crisis, whether that's colonialism, white supremacy, racism, and the patriarchy, those are the same ones that have harmed communities of color for generations. So when I think about the federal and climate policies and equity investments that have been rolled back and under direct assault, it's no accident that the targeting of climate and equity by authoritarian actors is intentional and calculated. And it's really about weakening movements and grassroots power. And there's a strong interplay between climate and authoritarianism, like the control over land and resources, criminalizing dissent are essential to authoritarian playbooks.

And so in this moment when the imperative is to fight for our country and to fight for our democracy, I'd contend that we can't have a democracy without a focus on climate justice. And so in this moment and in this context, that's what's energizing me, is making sure that folks understand that climate justice really is the antithesis of an authoritarian agenda. And we don't have to do this work alone. Like we have a whole infrastructure, the solutions projects connected to upwards of 350 plus grassroots organizations across the US that are working to, to transform communities right now and to build power, and to ensure that we all have the rights that our democracy is supposed to protect.

Kousha Navidar: It makes me think of what you brought up about the etymology of philanthropy. Its definition, meaning the love of humanity. So for you, how does love fit into the work that you do?

Gloria Walton: You know, when I think about the dominant theories of change and the world views really, that influence us and, and shape our democracy and capitalism right now. It's a lot about individualism, competition, the commodification of people and the places that we call home. And when I think about the communities and the grassroots organizations that the solutions project supports, it's flipping those world views on its head and it's actually practicing and demonstrating a different way. That's about interconnection, that's about care. That's about the abundance and sharing of resources. And it's about community recognizing that we don't have to do this work alone. So yes, philanthropy at its heart and in its true meaning is about love, which is why, as an organizer, after doing this work, working on the ground for nearly two decades, I'm trying to do my part to move more resources, capital, uh, and shine a light on the solutions that are already happening and underway. And these are solutions that are, yes, benefiting many local communities, but it's benefiting the broader democracy and society as a whole.

Kousha Navidar: Gloria Walton is President and CEO of the Solutions Project.Gloria, thank you so much for spending time with us and, and talking to us about your work.

Gloria Walton: Thanks so much for having me.

Kousha Navidar: One example of the kind of organization funded through The Solutions Project is Hoʻāhu Energy Cooperative Molokai. Ho’ahu is a community-owned energy company on this small Hawaiian island, where the majority of the population is Native Hawaiian.

Todd Yamashita: If you grow up on Molokai, you realize that the community here is like no other. So you're just reminded every day that we really have a responsibility to that.

Kousha Navidar: Todd Yamashita is a volunteer board member with the organization. He says that Molokai has some of the highest electricity rates in the country. And that can be tough on the residents.

Todd Yamashita: My neighbor, his electric bill was $700. He doesn't have a job. He has a 5-year-old son. And he's begging me for help.

Leilani Chow: 60% of Molokai residents are low to moderate income, and about 40% of those people live below the poverty line.

Kousha Navidar: That’s Leilani Chow, projects coordinator for Hoʻāhu.

Leilani Chow: Quite a lot of our people on Molokai live off grid, they burn propane, and then some people just don't have anything.

Kousha Navidar: Molokai’s electricity is so expensive because most of it is generated by burning fossil fuels - which have to be imported. Isaac Moriwake, an environmental attorney with EarthJustice, explains:

Isaac Moriwake: Hawaii's the most isolated land on this planet, and it's dependent on imported oil, which is a crazy thought, if you think about it. If the ships stop coming, we're screwed. We have no energy, and fossil fuels are expensive.

Kousha Navidar: But this community has rallied together, training their own members to install solar panels. They hope to provide cheap, reliable power to everyone who needs it.

Todd Yamashita: This is now or never. Molokai has never experienced such expensive electricity. If we fail at this, I, I, I am afraid to think about what it could mean.

Kousha Navidar: To help meet the need for home-grown power, Hoʻāhu offers fully subsidized tuition for Clean Energy Technician training programs. These programs provide photovoltaic solar courses, safety certification, and hands-on building experience. Participants come out of these programs trained and certified to construct small-scale solar systems.

I want you guys to hand me up these two panels.

Todd Yamashita: Solar happens to work really, really well in Hawaii. In six short months, we've graduated 12 clean energy technicians. We're already installing systems for our friends and neighbors. We are a family. We are creating jobs now in a community where there were no jobs before. We're giving people livelihoods. You know, we're teaching their sons and daughters how to become solar installers.

Okay. Oh, look at that. 110. We got solar coming off the roof.

Kousha Navidar: In the long run, the investment in renewable energy will almost certainly pay off, but coming up with the initial capital is a challenge for a small, relatively low-income community like this one.

Todd Yamashita: We have the most amazing board. We have the most amazing staff. I'm a volunteer. I get paid nothing for this. We're all doing this because it, it is exciting. I lose sleep at night because I know that if I can just raise enough money, if I can just find the right partners, if I can thread the needle, then you know, maybe we can make this work.

Kousha Navidar: For Todd Yamashita, this is personal.

Todd Yamashita: I’m trying to leave a legacy for my kids. Something that will benefit them and their peers. And the hardest thing about climate change is that where I own my family home, where I built my farm, when my kids are probably just a little bit older than I am, there’s a good chance that it’s going to be under water.

Kousha Navidar: EarthJustice’s Isaac Moriwake says that grassroots projects like this can serve as an example of how people can literally take power into their own hands – and not just in Hawaii.

Isaac Moriwake: I think Molokai can show how a community like this can come together and drive towards a hundred percent clean energy and achieve these goals from the people, from the community. Bottom up,

Kousha Navidar: The Ho’āhu Energy Collective interview audio was generously shared with us by the Years Project, a 501c3 climate media company.

Ariana Brocious: Coming up, why we need to make climate and environmental spaces more inclusive and welcoming for everyone:

Wawa Gatheru: And the common denominator was someone at some point would always approach me with this question on their face of. Oh, that's interesting that you're interested in this. And I'd go, well, why is that interesting? Because you're interested in climate, so why wouldn't I be interested in climate?

Ariana Brocious:That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious. Wawa Gatheru didn’t see many people like herself when she began to participate in climate and environmental activism. So she decided to change that. The Gen Z climate activist and Rhodes Scholar is the founder and Executive Director of Black Girl Environmentalist, a national organization dedicated to helping more Black girls, women, and gender-expansive people enter and lead in the climate space.

Wawa Gatheru: My story in regards to joining the climate movement, I think started before I was born. So I come from a long line of farmers. As far back as oral history goes back on both sides of my family, earth stewardship has been a part of our story. And when my parents immigrated to the US they did so because of lack of opportunity in Kenya, but also because of climate change, because they were experiencing a lot of the dynamics of what is now a 40 year long drought. And so for them, when they thought about opportunity for their future children, they factored that into their migration story in a lot of ways. So I have connected climate to my genesis as the years have gone on and I've better understood the reasons why my family went to the US. On a more specific aha moment end of things, when I was 15, I stumbled into an environmental science class, and as the story goes. Didn't wanna take the class. I thought I was gonna be a doctor, didn't do well in chemistry, and the only course that I could take was environmental science. And so I took that class and it ended up changing my life. I had an incredible teacher. Her name was Mrs. Rose, who did such a great job at connecting the dots between climate change and the very real dynamics that myself and my classmates were seeing and experiencing as well as including a chapter on environmental justice, which really opened my world to the ways that climate change doesn't impact us all the same, and the ways that specifically so many of the communities that I'm a part of, particularly the Black community across the diaspora and, and how climate change is disproportionately impacting us while unfortunately we aren't adequately represented in climate leadership.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. So when you were a kid, if someone had asked you to draw a picture of an environmentalist, what would you have drawn?

Wawa Gatheru: I would've drawn anything that didn't look like me. You know, I grew up with like so many other people feeling as though environmental work at large just required a really fancy science degree, like Patagonia, like liking to go hiking and, and camping, which is funny because now I love hiking and camping, but at the time, I hadn't had the opportunity to do that until I was in college.

Ariana Brocious: But it's not a prerequisite.

Wawa Gatheru: And it's not a prerequisite, but it's great if that's what you love to do, right? Now, I know that there's so many different ways that you can show up as an environmentalist, but at the time I, I certainly thought that there was also this requirement of perfection, and I just understood myself as a very imperfect person, and couldn't really see myself showing up in a way that I could be maybe, a perfect environmentalist.

Ariana Brocious: Hmm. I think you focus a lot on this question and need for more diverse representation in the climate space. And I just wanna explore that a minute because it's so powerful, especially I think as you've said, when you're a younger person, to see what's possible, to kind of look to the world as it is and, and be able to put yourself in it. So can you talk a little about your work expanding this idea of who is in the climate movement?

Wawa Gatheru: Yeah, and you know, it's interesting because I experienced a lot of those dynamics. Once I decided to join the climate movement when I was 15, I started showing up at random climate events. And showing up at different community meetings and joining clubs at college. And something that really hit me was that it seemed as though in so many of the spaces that I was in, I was the “only one.” I was oftentimes the only person of color. I was almost certainly the only Black person. Almost all of the spaces that I frequented. And then when I was in climate spaces outside of my university, I was oftentimes the youngest person by like at least 20 years. And the common denominator was someone at some point would always approach me with this question on their face of, Oh, that's interesting that you're interested in this. And I'd go, well, why is that interesting? Because you're interested in climate, so why wouldn't I be interested in climate? And I realized through so many of those circumstances that unfortunately the mainstream climate movement, especially at that time, so we're talking like eight years, seven years ago, wasn't as diverse as I think it is now, even though there's a lot of improvements that we can make. And so in a lot of ways there was some trauma embedded in my pursuit to help cultivate spaces for more people of color, and specifically Black girls, to see themselves in climate work, especially as I continued to grow in my scholarship and advocacy and began to really understand that there had always been a long, long, long legacy of, of Black people, folks of color, indigenous folks, stewarding the land and having a really deep, ancestral connection to earth stewardship and even connecting my own family's history to that legacy. And so I think a huge part of it has been also uncovering the very real history that unfortunately I just didn't get to access as a student and making that more accessible to other people.

Ariana Brocious: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. So you touched on this idea of the disproportionate impacts of climate across this country, across the world. Elsewhere in this episode, we talk with Gloria Walton and she talks about this need to shift the narrative about those most impacted by climate disruption from victim to victor. So how do you see frontline communities portrayed, you know, in the media in like a large sense?

Wawa Gatheru: Yeah, that's a great question. And shout out to Gloria. She's wonderful. It's interesting because in some ways, I'm in a bubble. I've found so much of my climate community in the past five years, so I'm actually surrounded by really great climate storytelling. Often, like I am surrounded by folks who engage in Hollywood and are really interested in telling authentic stories that are in direct collaboration and in communication with frontline folks. I am constantly with frontline folks as being someone who runs an organization for black youth, who is a demographic that is a frontline community, in regards to environmental hazards and the climate crisis at large. But I am also very aware that that perception is not everyone's perception. And I've had to build that for myself really intentionally. And so I say that all to say, there's still a lot of work that needs to be done and I think that there's this dichotomy that exists, particularly on social media, where social media really rewards fast, simplified narratives that oftentimes fall into misinformation and voyeurism, especially when it comes to telling stories of climate disaster, and maybe sometimes sidelines the climate resilience and even climate joy that can exist when you get involved. Whereas climate storytelling always must lead with truth and nuance, and sometimes the two can feel at odds. But I'm a firm believer that you can do both at the same time. It just, again, requires intention and requires the communities themselves to be in the front seat.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, I want to unpack that because I think you're a very talented storyteller and you work in this space of social media, which as you said so accurately really does reward, like simple, easy, digestible, you know, bite-size, whatever. And a lot of your social media posts are based in some sense around facts. You know, like the Arctic is heating up four times faster than anywhere on earth. Or the US is currently producing more oil and gas than any petro state in history. We talk a lot on our show about how sometimes facts aren't what compels people. There's been science around the impacts of climate change for decades. People have known it hasn't shifted the action that much. And what really captivates people are stories, you know, like human stories. So, how do you kind of balance those when you're creating things to put on your feeds?

Wawa Gatheru: To put it plainly, I believe that facts ground us and that stories move us, and that I see them as partners, not as opposites. And so I think that anytime we talk about climate data's grounding all of that, right? Like we understand that the climate crisis is happening because we have a plethora of data and also we have a plethora of lived experience. And so that data helps people understand the scale of the crisis. Stories do that as well. But I think where stories really have a unique hold on people is that they allow people to see themselves inside of it. I think we're at a point where we have data paralysis. We got so much data, there's always a report. And those reports are so important, obviously, but we're not gonna report our way out of this in, in, in transforming people's minds and hearts. It's through telling stories and it's through connecting with people on an emotional level because climate change is a deeply emotional problem. And this is where we have to really move from this technocratic language of climate change. and, we need to infuse this idea that there are ways for us to solve this crisis and that the climate crisis, in my opinion is an opportunity for us to finally build a world that's just for all of us, and that there are few other opportunities for us to do that as a species.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. So you've said that narrative change comes down to crafting a narrative that dismantles another prevailing narrative that can be harmful. What, what harmful climate narratives are you working to dismantle? Do you want to even give them space and list them, or would you rather focus on the ones that you wanna see?

Wawa Gatheru: You know, I think if anything I'm, I'm a huge supporter of nuance. So much of preliminary mainstream conversations on climate makes everything seem black and white. And I don't think it's that simple. And our lives are not that simple. So I don't know why we always default to that. And so I really like to encourage conversations of nuance, and I think a great example of that is when we talk about climate grief, eco anxiety, rage, anger, hopelessness, all these very complex emotional responses to climate change that I feel that, at least in my personal experience, when I first started really feeling those things, I felt so embarrassed and I felt like I was a failure. I was like, how can I call myself an environmentalist? How can I say that I do climate work? How can I say that I'm a proponent of environmental justice when I'm having cold sweats in the middle of the night? Like that's not something people wanna hear on stage. They wanna hear someone who's like, you shouldn't feel these things, et cetera. And so now I'm very open about those feelings with people that I don't know, with people that I do know. Because I think that we have to reframe these conversations and say, okay, the reality is, is that the discomfort that so many of us have around the climate crisis is a sign that you're awake to what's happening. In fact, I would be worried about someone witnessing and experiencing climate disaster and feeling nothing. It is so human to feel all those things and taking a step further, I think we have to feel it. We have to feel it. We have to have better conversations and actually have some sort of literacy, like emotional literacy of like how to navigate these things and then do something with it. Those emotions are incredibly powerful. Like angry people get a lot of sh** done. Like when I'm angry, like that's when I'm like –

Ariana Brocious: It can be, it can be empowering.

Wawa Gatheru: You know? And I think we have to let people know that, and that starts with being honest with ourselves and then with others.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. There's so much in there I wanna respond to. I just, I agree wholeheartedly that you have to be a sentient being, right? Like you can't sort of operate in this dispassionate space around facts and figures. And that by feeling those emotions fully, as awful as it is, sometimes really connects you to the reason for why we're doing the work, right? I wanna pivot back for a second to the work you're doing in creating more inclusive spaces, because I think this is so fundamental. So your group, your organization, black Girl Environmentalist now has more than 2000 members and is recognized as one of the largest black youth led organizations in the country. What does that growth tell us about the demand for more inclusive climate spaces?

Wawa Gatheru: Yeah, it's been really exciting to see the way that the organization has scaled, especially since we started out as a digital page, like we quite literally. Began with the most Gen Z genesis, which is an Instagram page. Mm-hmm. And I was just super lonely dealing with all of these prevailing conversations and just really desperately needed community. And so we started out as an Instagram page that would move to Zoom and have these huge video calls where people would talk about their experiences in the environmental space, which then moved into virtual happy hours and virtual panels and networking hours.

Eventually after I finished my graduate studies at Oxford, I decided to take a chance on this little digital community and see if there was a way to utilize all of what I had learned from the community that I had helped facilitate online for several years and transform it into an in-person organization that could help address so many of these really unique issues around pathway and retention that specifically impacts black girls and black gender expansive youth in particular. And so now, our organization has three impact areas, community empowerment, narrative change, and green workforce development. And through the lens of those impact areas we have six national programs that do their best at addressing these prevailing issues. I just got back from Oregon, actually we were there last week and it was just so beautiful to see 16 early career black women and black gender expansive emerging climate leaders be so firm in their commitment to. Climate work and who now have these experiences, they're going to hopefully continue to ground them as they grow in their leadership. And I'm very, very excited to watch them. And, and I feel like the work that BGE is doing as an organization that is made up of the very demographic that we're working to support really gives us this unique edge and ability to address in really intentional ways.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. That's so empowering. Just hearing you describe how much thought and care has gone into creating a program like that, To have those people take more leadership on and continue to evolve in their careers. You've talked about fighting for an age of quote, unprecedented care. What does that look like in practice?

Wawa Gatheru: I think it means a lot of different things. I've learned a lot from abolitionist frameworks to be honest and abolitionists about what climate justice really means to me and what it is that I'm fighting for. And I actually wish we had more space in the climate movement to dream and to think radically about what it is that we're building. And I completely understand why there is a lack of space given to that because the urgency of the crisis is just so overwhelming, and I think we have to get in a practice of doing that. And so I've been trying to lean into that practice more and more this year. That was one of my New Year's resolutions that I've actually kept up with. I would love for, you know, us not to have to build a climate movement made in the image of all of us. I wish we didn't live in a world where children have to be activists. And those are things that I'm, that I'm thinking about and would like to have actualized. And I don't know if they're possible in my lifetime, but I'll do my best to contribute to making them a reality for someone at some point.

Ariana Brocious: Wawa Gatheru is founder and executive director of Black Girl Environmentalist. Thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Wawa Gatheru: Thank you so much for having me.

Kousha Navidar: Hey everyone, it's Kousha and Ariana. We are coming to the end of our show, and that means it's time for climate one more thing, Ariana, uh, what do you got?

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, I read an article this week that there's new research out in the journal nature that found there are far fewer good places to store carbon dioxide underground than we previously thought. And this is a little bit of a not good news story, um, because according to the article that I read in grist. That's only equal to about as much carbon dioxide as would cut global warming by 0.7 degrees Celsius. And previously we have thought that we could store enough carbon dioxide to equal about six degrees Celsius. So that's a huge difference. That's less than one degree. Uh, and it means that we really have to focus on reducing emissions before they happen, as many people have argued, rather than this kind of after the fact solution.

Kousha Navidar: I saw this article, and you're right, it's not great news. There are other strategies just to like, you know, think outside the carbon dioxide sequestration box that we did an episode about super pollutants, atmosphere pollutants besides carbon dioxide. That could definitely, or, or like low hanging fruit. Cleaning up the air. Yeah. So it, it is a bit of a bummer to to hear, but there is a way forward I think.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. It's good to know what we can and can't do. And again, I think that a lot of the consensus broadly in the climate space is that carbon sequestration was never really gonna save our bacon. Uh, it was like one tool in the tool basket. So I think it's still remains there, but it's less powerful than maybe we, we thought. Kousha, what about you?

Kousha Navidar: So, yeah, I, I can go as well. So a few weeks ago I asked for advice about running on a treadmill and Ariana, I got some advice and I was so delighted that I did. I just wanted to give a shout out to Allison, to Carlo. And to Charles, who are three of our wonderful listeners who all emailed me and gave me some good advice, some, some highlights. Carlo suggested that I do ladder intervals to break up the miles. Alison said, go run somewhere else. Take a road trip and find someplace that would be fun. And one of my favorite things, I just wanna shout out, Charles, he wrote me a two line email. All he said was, listen to Climate One episodes. That's what I do. So I just wanted to thank everybody listening right now for helping one guy make, make treadmill running a little bit more fun. And if you have more advice, I'm, you know, my, my email's always open, kousha at climate one dot org.

Ariana Brocious: That's great. I'm so happy to hear that people responded and you got good advice. So that's our show. Thanks for listening. You can see what our team is reading by subscribing to our newsletter. Sign up at climate one dot org.

Kousha Navidar: Climate One is a production of the Commonwealth Club. Our team includes Greg Dalton, Brad Marshland, Jenny Park, Ariana Brocious, Austin Colón, and Megan Biscieglia. Our theme music is by George Young. I’m Kousha Navidar.