Ken Burns, Rosalyn LaPier and The American Buffalo

Guests

Ken Burns

Rosalyn LaPier

Summary

On Climate One we talk a lot about climate levers – big tools for change – and possible futures. But equally important is our past, and the historic patterns of racism, injustice, and resource extraction that have led us to today’s crisis.

The history of the westward expansion of the United States is full of human and cultural genocide, land theft, and destruction of animals and resources. The bison, or American buffalo, tell the story of the unchecked greed and exploitative nature of colonial settlers and their corresponding efforts to remove Native Americans from lands they had inhabited for hundreds of generations.

The saga of the American Buffalo is the latest undertaking by Ken Burns, a documentary filmmaker fascinated by our nation’s history.

“You have to know what happened. You’re not diminished, you’re actually made stronger by learning the complicated parts of our history. You’re weakened by soft-selling it,” he says.

These charismatic megafauna of the American West ruled the heart of North America in such millions as to be almost incomprehensible today. For millennia, this totemic animal lived in symbiotic relationship with grasslands throughout North America. Then – in less than 100 years – new settlers and hunters reduced their numbers from 30 million to the mere hundreds, while simultaneously glorifying and capitalizing on them as our iconic national animal.

“We put them on a nickel, with an Indian head, fetishizing and romanticizing two groups that we spent a century trying to get rid of,” Burns says.

The story of the American bison has parallels to the mentality that drives the climate crisis – thinking we can keep extracting and extracting with no consequences.

“We would define bison today on the Great Plains as a keystone species,” says Indigenous environmental historian Rosalyn LaPier, “the most important animal or plant within an ecosystem, so that when you pull that particular animal out of that ecosystem, there's this cascading effect, almost like dominoes falling, right, of how the ecosystem does not work or function as well as it could anymore because that keystone is gone.”

Ken Burns says his films have been exploring the same question for decades: “Who are we?” In “The American Buffalo” he probes our human ability to destroy animals and people, as well as the human ability to protect and restore them. The film carries an undercurrent of resilience, both of the species and the Indigenous peoples who survived this brutal era and remain here today.

“I think one of the things that Native people have learned over the past 100-plus years and what happened with bison and with their own personal story is that the potential always exists for the federal government to change their policy,” says Indigenous environmental historian Rosalyn LaPier. “So right now we're in a time period of self- determination for Indigenous people, but also restoring the bison and restoring grasslands on the northern Great Plains that are part of the ecosystem that bison use. But the potential always exists for the pendulum to swing in the other direction.”

Episode Highlights

8:00 Ken Burns on manifest destiny

10:30 “We’ve sanitized and minimized the painful truths of American history”

13:30 The bison as a model of de-extinction

18:00 The colonial settler resource extraction mindset

22:00 Transformation and development of people in this history

35:00 Rosalyn LaPier on relationship between bison and Indigenous peoples

38:00 Bison as Great Plains keystone species

44:00 Ken Burns on his National Parks series

53:00 Rosalyn LaPier: “the potential always exists for the federal government to change their policy.”

Resources From This Episode (1)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One, I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: On Climate One we talk a lot about climate levers – big tools for change – and possible futures. But equally important is our past, and the historic patterns of racism, injustice, and resource extraction that have led us to today’s crisis.

Ariana Brocious: Right, a crisis that is still unequal today, affecting historically marginalized communities harder than others. So, naturally, that leads us to talking about bison.

Greg Dalton: Bison, you mean buffalo?

Ariana Brocious: Yes. Though the confusion is understandable. The scientific name for the animal we’re talking about is the bison. But so many people still refer to it as the American Buffalo that in this episode, we’ll be using both names interchangeably. Bison or buffalo, we’re talking about the charismatic megafauna of the American Plains, this icon of the American West that ruled the heart of North America in by the million as to be almost incomprehensible today.

Greg Dalton: The history of the westward expansion of the United States is full of human and cultural genocide, land theft, and destruction of animals and resources.

Ariana Brocious: And bison tell the story of the unchecked greed and exploitative nature of colonial settlers and the corresponding efforts to remove Native Americans from lands they had inhabited for hundreds of generations.

Ken Burns: You have to know what happened. You’re not diminished, you’re actually made stronger by learning the complicated parts of our history. You’re weakened by soft-selling it.

Greg Dalton: Documentary producer Ken Burns knows this well. In his latest work, he explores these themes through the story of the American Buffalo.

Ken Burns: We put them on a nickel, with an Indian head, fetishizing and romanticizing two groups that we spent a century trying to get rid of.

Greg Dalton: Ariana, I was really hit in the gut watching this. I saw the roots of many problems underlying our climate conundrum today. Hunters removing hides from bison and leaving the rest of the animal to waste on the plains. Mad rushes for gold, feedlots for cattle that looked to me like the first factory farms.

Ariana Brocious: It’s sort of the same issue as the climate crisis, thinking we can keep extracting and extracting with no consequences. However, there’s also an undercurrent of resilience in this film.

Greg Dalton: Ken Burns says his films have been exploring the same question for decades - who are we as Americans? In this one he probes human ability to destroy animals and people and human ability to protect and restore them.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, it’s worth watching. The American Buffalo premieres on PBS stations this week. Today we have an in-depth interview with Ken Burns, as well as my conversation with Rosalyn LaPier, an indigenous environmental historian featured in the film. Greg, take it away.

Greg Dalton: In a New Yorker profile of you from a few years ago, I read that there are a few items that you always carry, including a button from the uniform of a soldier who participated in the D Day landing, and a ball that a friend picked up at Gettysburg. Do you still carry that?

Ken Burns: I do. I do. I, I, I have first and foremost, after the civil war series came out, a woman wrote me a wonderful letter about the complexities of the epic story of it. She related it to the Bhagavad Gita, the great Indian spiritual narrative with its love and hate. And she crafts metal and she crafted a heart, a feeling heart, she called it. It was a little indentation and I kept it in my pocket and I immediately asked her for a couple more for my then two daughters. And now that I have four, I've gotten two more and I've kept that to which I've added the button that a friend of mine gave me that was worn by a relative at D Day and a few other things that get collected.

Greg Dalton: Powerful things, yeah, to tactilely connect.

Ken Burns: Yeah, and they're just a way to sort of unite a lot of the disparate aspects of the enterprise. You know, I've sort of admitted that we've made the same film over and over again. And I think it's true. All of them ask this question about who are we.

Greg Dalton: In making American Buffalo, was there a new insight into who we are? Through the story of the bison?

Ken Burns: I'm not sure, Greg, that I can satisfactorily identify that for you, but I can begin to describe all of these are accruals that are imperceptible. Like, you know, a pearl is in fact an irritation, you know, and then we value it because of these imperceptible layers that are built up. And so each project does offer some other view, but it doesn't have a kind of directly articulated sense, that isn't to say, Oh, well, this film gave you these building blocks. These are unformed, they're emotional, they're deeply personal. Sometimes they're spiritual, their connections with people, the subjects, obviously. So I think in Buffalo, a project 30 years, and I'm so grateful that we waited is that it permitted us to benefit from new scholarship. It permitted us to be older enough that we didn't need to just in a knee jerk fashion acknowledge other points of view or other peoples, other cultures, but actually yield to them so that we could let go of some of the paternalistic, perhaps even patronizing viewpoints that come even from the best intentions and permit people who have 600 generations of experience with this animal to have their life ways, have their spiritual beliefs, have their existence govern a way to look at it. And not just be, uh- huh, well, that's just a subset of us, meaning white European Americans. And so it, it, it permitted us in a way, a kind of openness that really unexpectedly rearranged all my molecules, hearing from the predominance of Native American voices, scholars, poets, biologists, historians, park rangers, descendants, people who could help communicate a little bit about that 600 generations of relationship with this animal, as opposed to at best, the six that, that some of us might be able to claim.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, while watching American Buffalo, the relationship with Indigenous people and the landscape hit me hard and early. George Horse Capture says:

George Horse Capture: “With the westward expansion, everything had to get out of the way. You’ve probably seen the old painting, Manifest Destiny. They show everything fleeing in front of this horde of wagon trains and people on foot and horseback. When Europeans come in, everything natural has to get out of the way. It’s just a matter of fact.”

Greg Dalton: It just really hit me in the solar plexus watching how quickly when European settlers come in that, that, that manifest destiny is manifest. And I'm interested in how you see that contrast and how it shaped the story because that comes in early and hard.

Ken Burns: Yeah. I think it's really a clash of two visions of a relationship to the natural world as our commentators say, you know, one is interconnected and intertwined that see the Buffalo as brethren, as kin, as relatives. And the other, which is sort of the position of we're the dominant species. What part of get out of the way, don't you understand that we're civilized and not savages, which is already another dislocation from the idea of the equality of human life. It becomes less valuable if you are lesser, you're an other, it's devastating. I really think it's devastating for us to relive and to show, but it's, it's something we, you have to know what happened. You're not diminished. You're actually made stronger by learning the complicated parts of our history. You're weakened by soft selling it, by, you know, excluding different parts because you're afraid to traumatize. There's a wonderful woman who teaches history in Maryland who was born in Germany and she said, look, I've been taught from an early age about our history and arguably the Germans have the worst and done a great job of teaching that history. She goes, I'm not traumatized and you literally can't walk anywhere in Berlin without tripping over the exhibition of it, then the cobblestones embedded in the, in the sort of the ground, the earth, are the crimes of their past. And they've done a remarkable job of it. And we, on the other hand, being the greatest country on earth, have actually minimized that history, made it superficial, sanitized it, and kind of Madison Avenue selling job and, and if we wish to be exceptional or remain exceptional, whatever your opinion is, you got to be incredibly self critical. You don't get better and you're not the best, period, if you're not that way.

Greg Dalton: So, getting to those painful truths and being self reflective about who we are, is it fair to say that America was built on stolen land with stolen labor?

Ken Burns: Duh. Yeah. No, I mean, it's, it's, it's, um….

Greg Dalton: But that's not the Madison Avenue story that we hear, that we tell ourselves.

Ken Burns: It is foundational. Our revolution, which we see as a kind of sanitized, you know, 55 white guys in Philadelphia thinking great thoughts. That happens at the Constitutional Convention. And there are some really magnificent compromises and some really tragic compromises that are done, but the tragic ones are very simply, we are going to assign to the federal government the question of taking care of the Indians. The war starts, the revolution starts as much over Indian land as it does over taxation and representation. And it's from ordinary folks who just want a piece of land to farm because in Scotland or Wales or Ireland or England, their family has worked the land for a lord for a thousand years or more, and they now have a chance to do something else. You can understand the desire, but it's not their land. And it's the land of people who don't really understand it. You know, George Horse Capture Junior in the film at one point goes, “my cattle, my land,” and you realize, oh my God, our whole notion, the momentum, the inertia of ideas about property, right? Have conveniently forgotten that, you know, just a few generations ago, it wasn't our property. It was somebody else's who didn't think of it in the same way that we did with deeds and over to that tree and over to here, there was a more symbiotic sense of a relationship with nature. And then of course, coexisting with this is chattel slavery perpetuated even after the man who owned hundreds of them proclaimed, distilled a century of enlightenment thinking into one sentence, that begins, we hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal. That's our creed. I just think lots of stuff is there to be examined. And one of the ways that a story about the American buffalo permits you to do is you're doing, unlike the other biographies we've done, the biography of an animal. And you would think that this would lead you into sort of nature films or, or science. And it's not, it's really a way to see in their eyes, through their eyes, the relationship with the people they had for 12,000 years and the more recent relationship and the great tragedy that takes place on the Great Plains and let us also not, not ignore the fact that this is also a very positive story of a parable of de-extinction and in the midst of climate change, when we will begin to see more and more large megafauna, charismatic fauna heading towards extinction. We do have this model of a man made disaster as climate change is, different sort of thing, slaughter and then bringing us back from the brink. Now there are 80 tribes in the Inter Tribal Buffalo Council that are helping to bring bison from various locations and bring them back to various tribes who have had that relationship severed. And they're not just going to keep them as zoo animals. They're going to eat them, but in a sustainable way and perhaps help to repair some of their horrific nutritional damage that has been done to them over the last 150, 250 years.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, that's one of the parts I really appreciate is how they eat them and they worship them and cause they're dependent on them and that they hold that kind of, it seems contradictory to some people to worship something that you eat.

Ken Burns: Look, look, we, we sit down many families, certainly at Thanksgiving and we say, grace, we are grateful for the food. This is a small, perhaps now glib, perhaps we've forgotten the initial connection of what native peoples have done. The earth has given us this beast. We will use every part of it from the tail to the snout, even it's snort. Gerard Baker says, because the sounds of the buffalo work themselves into rituals. Gerard is a Mandan Hidatsa Indian in what is now North Dakota. But, but we are going to realize that there is this incredibly delicate and incredibly obvious symbiosis that by taking a buffalo, we have elevated this species to, and that sustains us. We've elevated the species to the highest of spiritual dimensions. And we know this, everybody knows this. I sort of think that somewhere along the line, consciences are pricked and things happen to Buffalo. We begin to save sometimes for the wrong reason. Sometimes for the right reason, we put them on a nickel with an Indian head fetishizing and romanticizing two groups that we spent a century trying to get rid of. But somewhere underneath that is our, is a prick of conscience that we know, we know that these two developing symbols of us, of the United States, the Native American and the buffalo, Are not us. We've done our best to get rid of them. And yet we know deep down, they know something we do not know. It only follows for George Horse Capture to come on and say, I just have to ask, why do you destroy the things you love? It's a really good question for Western peoples.

Greg Dalton: Right, there's so much there. I actually have gone to the American Prairie, which used to be called reserve in Montana. I didn't really understand what they were trying to do, and now after seeing American Buffalo, I was like, okay, I get it. And this is, I guess, a parable of how we can restore the buffalo. We can restore a lot more that we've destroyed through greed and, and extraction. On Climate One, we talk a lot about extraction of fossil fuels, other resources. One line in American Buffalo is when the writer Dayton Duncan says the worst line that can be said for indigenous people is “then gold was discovered on their land.” All sorts of bad things then happen in California, Montana, elsewhere. So how do you see the story of the Buffalo relate to the story of mining and other forms of extraction?

Ken Burns: So it's so important. I imported to this film from uses in two other films, the West and the National Parks, this wonderful quote by Lord James Bryce, who, 50 years after Alexis de Tocqueville came through the United States, he would eventually be the ambassador from Great Britain to the United States. And he has this bittersweet thing. Like, what's your haste? Why this haste? He asked, you know, we have cities bigger than yours and we're still not happy. And that don't you wish to go back to that moment, as he said, when you burst into this splendid, silent nature, he forgets it wasn't so silent and that nature was filled with lots of Native Americans. Um, but the point is well taken that there is in manifest destiny, this idea that we are destined to o’er spread the continent for our yearly multiplying millions, as I think it's O'Sullivan says at the middle of the 19th century that we just bulldozed over everything. We looked at a stand of trees and thought: board feet. We looked at a river and thought: dam. We looked at a beautiful Canyon and thought: what minerals can be extracted. We have been acquisitive and a lot of that acquisitiveness has then permitted the kind of slaughter that took place. The market demands for leather belts, you know, first it was tongues and then it was leather belts. Leather was the fifth largest industry. The belts drove the machines of the industrial revolution, but you went out there and you just shot the buffalo for the skin, you left all that meat, depriving native peoples of the sustenance that they needed. And then all of a sudden somebody goes, wait a second, this is gonna help both of these problems. And that acquisitiveness spills over into murder, genocide, starvation, I mean, I don't know what, what's the right word, but it's a tragedy of which we are all kind of co-owners of it. And we are also participating in it.

Greg Dalton: Today on Climate One, a conversation with Ken Burns about the American Buffalo. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods.

You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. On our new website you can create and share playlists focused on topics including food, energy, EVs, activism.

Coming up, it can be easy to put historical figures into clear boxes: hunter, conservationist, Indian fighter, Indigenous ally. But real history, and people, are more complicated than that:

Ken Burns: I think we tend to think of things as either on or off. We’re in a kind of binary world. And I think that just doesn't exist. There's nothing binary really in nature. And so I think what happens is that we have to permit people to grow and evolve and be able to have narratives that tolerate that.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: In 1874, Congress sought to pass the Buffalo Protection Bill, which outlawed killing female bison by “non Indians.” This was a moment of growing awareness about the way white hunters had decimated the species.

Ariana Brocious: But President Grant did not sign it. And the bill died. And the slaughter of the bison continued.

Greg Dalton: As documented in Ken Burns’s latest film “The American Buffalo,” many powerful people realized killing the bison would also hurt Native Americans – and did so intentionally. These are the words of Theodore Roosevelt, written before he became president, read by actor Paul Giamatti:

ROOSEVELT CLIP: “While the slaughter of the buffalo has been needless and brutal, and while it is to be greatly regretted that the species is likely to become extinct, it must be remembered that its destruction was the condition necessary for the advance of White civilization in the West. Above all, the extermination of the buffalo was the only way of solving the Indian question, and its disappearance was the only method of getting them to at least partially abandon their savage mode of life. From the standpoint of humanity at large, the extermination of the buffalo has been a blessing.”

Greg Dalton: What do you feel when you hear that?

Ken Burns: I just unbelievable, unspeakable sadness. I've worked with Paul a few times and we just like look up and shake our heads. Um, you know, we tend to, when we tell stories in history, we tend to fix people at. At one particular point, oh, they're this thing, a white hat or a dark hat, you know, is the simplest thing, a cowboy or an Indian. There's always oppositional stuff. And it's never as simple as that. And I think this story details the transformation, the development of lots of characters, including Theodore Roosevelt, whose inexcusable, white supremacist, unbelievably brutal comment, you know, he goes out there and he wants to kill one to put up on his wall. And then when he realizes they're all being killed, he then sees this as an agency of policy with regard to the taming of the West. And that's, this is what we did too. And then he also becomes, you know, a conservationist. First conservation is born among hunters, which a lot of people don't really remember or accept and people who enjoy hunting did not want to lose the thing that they were hunting. And so they realized there had to be some sustainable way to do it. And he migrates even farther. I don't think he ever loses completely the reprehensible white supremacist viewpoints, um, the things that subscribe to aspects of eugenics and a lot of the characters in our film are like that. Other people make bigger, bigger moves. I'm thinking of Charlie Goodnight in the panhandle of Texas, who starts off as a ranger and an Indian fighter and killer and a killer of buffalo. He wants cattle in the Palo Duro Canyon. He's got the first ranch there in the panhandle. But later on, his wife asked for him to save some calves and she's lonely and they build a herd and he eventually becomes quite close to the native tribes that he'd spent a long time, you know, killing and pushing onto reservations and even in, you know, an enemy of his, Quanah Parker of the Quehada branch of the Comanches, they become friends at the end and he's offering some of his buffalo for them to slaughter for their rituals because they have none and it's impossible to have that. William F. Cody, Buffalo Bill, you know, bragged about killing over 4,000 of them. And then suddenly realize that, you know, if I'm going to continue this Wild West thing, which is making him rich, I've got to have buffalo. And so I need to save them too. So there are people who are doing it for, as I said, lots of, you know, really good reasons and some of them not so good reasons, but the buffalo gets saved despite the fact that, you know, sometimes these objectives make for strange political bedfellows.

Greg Dalton: I'm glad you mentioned Quanah Parker because I'm ashamed at how little I learned about, um, Native American history in some fine schools and reading Ishii, Last of His Tribe told me that they were all gone. They're still here and I've come to, to talk to and get to know some Coast Meewok where I live north of San Francisco and I hear from them, we don't want to be perpetually portrayed as victims. And Quanah Parker is a Comanche warrior in Oklahoma who helps his people adapt to reservation life. He owns a large house, herd of cattle with 500 head, hired a white man to tend his 150 acre farm. I'm curious to hear a little more about Quanah Parker and how he typifies Americans trying to live in two worlds.

Ken Burns: You're talking to an anthropologist’s son, whose map above my bed had the political divisions of the states, but the states weren't listed or else they were in sort of half tones and it was all the native tribes. And my father showed me the book of Ishii and the film of Ishii. And I think we tend to think of things as either on or off. We’re in kind of a binary world in our politics. It's, you know, one thing or the other in, in our computer world and our media culture, it's one thing or the other, a one or a zero. And I, I think that just doesn't exist. There's nothing binary really in nature. And so I think what happens is that we have to permit people to grow and evolve and be able to have narratives that tolerate that. And Quanah goes a really long way. It's a very impressive story as is Charlie Goodnight’s. Michel Pablo in up near the Blackfeet reservation who had the largest herd, he's trying to sell it to the United States. Nobody wants to buy it. So the Canadians want to do it. Then he's a traitor for selling our buffalo herd to the Canadians and he can't get all of them. You know, rounded up. And so some they create a buffalo reserve near his high, but they won't let in his stray buffalo and then they get killed. I mean, it's you cannot make this story up. There's no fiction writer in Hollywood who could do it. But at the heart of it is understanding the kind of transformations that people make, however short they are. There's a few people in this film. They're central to our story that just move a few steps. Maybe TR moves a little bit more than a few steps, but certainly not enough. And then others who provide us with. extraordinary examples of how people can change. And I think, therefore, it helps us escape the pernicious prism of affixing people at one point. Oh, they're gone. They're victims. They're this, you know. There are the, for example, the National Bison Refuge, I think it was called just above Missoula, has just been turned over to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes. And they're running it and they changed it to the buffalo thing.

Greg Dalton: And land back and land rematriation is a national trend.

Ken Burns: It's huge. And, and one of our consulting, uh, producers, a descendant of Quanah, from the Quahada band of Comanches, Julianna Branagh made a short film to accompany our film called Homecoming. One of the most moving scenes, it's, you know, 15 minutes long, one of the most moving scenes is a Native American from Wind River in Wyoming who is rematriating buffalo to various tribes. And he takes them all the way east to the Menominee in Wisconsin. And these people have been separated from their buffalo for 250 years, right? It isn't just a hundred or 150 years from the Great Plains, the Northern Plains or the Southern Plains. And the look in the eyes of the buffalo and of the people, whereas if they're like, you know, you just, all the tales of somebody went off to war and, you know, it's, it's Odysseus, you know, you come home and you go, there you are.

Greg Dalton: Well, Quanah Parker cried when he saw the buffalo coming back.

Ken Burns: Of course. Of course. I mean the first reserve that Roosevelt creates for wildlife is in the Wichita Mountains of Oklahoma, whose highest promontory is now called Mount Scott, out of which the Kiowa legend is where all of the buffalo came out of Mount Scott to be given to the Kiowa people. And at one point in the middle of the slaughter, Old Lady Horse reminds us of the vision of one person getting up at dawn and seeing them filing silently back into the mountain. And, and, and here to just complete the you can't make it up story, where do they get the buffalo to seed this refuge in Oklahoma? Oh, they have to order it from the Bronx Zoo. And buffalo from the Bronx Zoo are packed onto trains at the Fordham Railroad Station in the Bronx in the largest city in North America and shipped by railroad, the very, you know, agent of the destruction of Native lands in the Great Plains. We've passed through the Great Plains, but as soon as we have railroads, we can populate the Great Plains. And destroyed all their buffalo, so we have to ship them back to, as we said, their new old home.

Greg Dalton: We’ll come back to my conversation with Ken Burns later in the show.

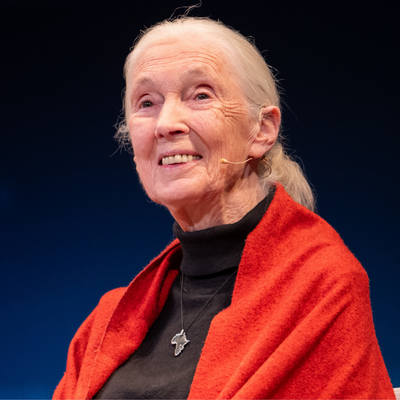

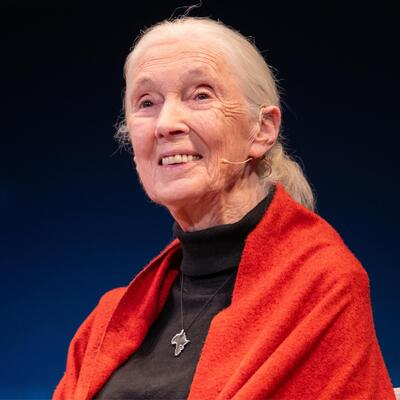

Ariana Brocious: One of the key voices featured in The American Buffalo documentary is Rosalyn LaPier, an Indigenous environmental historian and ethnobotanist. I talked with Rosalyn about the role of bison on the Great Plains ecosystem and in Indigenous culture.

Rosalyn LaPier: I grew up primarily on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana. And one of the field trips that we would take in the fall was to go to the fall time roundup that they had at the National Bison Range, as it was called. Now it's called the Salish and Kootenai Bison Range.

Ariana Brocious: Because it's under the ownership of Indigenous people again, as opposed to the national government, right?

Rosalyn LaPier: Yes. So, when the management and ownership switched over from the federal government back to the Salish and Kootenai tribes, they changed the name from the National Bison Range to the confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes bison range and, but they just call it the bison range now too.

Ariana Brocious: What was it like seeing a bison? Had you heard stories from your family about them before you actually saw one in person?

Rosalyn LaPier: Well, the stories I had heard about bison were not really of them. As like an animal, so to speak. I had heard a lot of stories of the connection between humans and bison as part of the supernatural realm. And so a lot of the stories I had heard about not just bison, but sort of other kinds of animals was that they were kind of, because they were from the supernatural realm, that they were often in my mind, at least, um, it's kind of these very fantastic, um, images, um, of, of bison who could talk and who could fly and who could, um, had different types of, um, Actions besides just being an animal. And, uh, and so when I first saw bison that were animals, um, it was not the same, uh, as as what I had imagined. Um, in my mind

Ariana Brocious: They're pretty big. The ones I've seen are, I mean.. Even seeing them on a video doesn't compare to seeing them in real life. They are very big animals.

Rosalyn LaPier: Yeah. And most of us kids who grew up, um, you know, again, primarily on the reservation, we had been around animals, you know, our entire lives. We had been around horses, we had been around cattle. And, um, so we had been around domesticated animal species who are quite large. And, um, And so being around a bison that can sometimes seem as big as a horse, uh, but who have a completely different, um, type of animal behavior because they are wild, they're not domesticated. Um, that's really different than being around a horse that is a domesticated species that are usually quite gentle, um, especially if they're trained. So. So, you know, being around, being introduced to bison and seeing them in that kind of situation where they were being rounded up, so they were being, um, they are being asked, so to speak, to behave in an unnatural manner, which is to corral them, um, Uh, and bring them together in a giant corral. And the reason the bison range did that, and they continue to do that to this day, is they, they do need to control the numbers of bison that are there. Um, although it is a really large area, it's, it's not that large. And so they do need to control the number, um, of bison to only a few hundred, um, in that area. And so each year when they do the roundup, they, um, decide which bison are going to be sold. And those bison get sold, um, to the general public, um, they get sold to farms and ranches, they get sold, um, to, uh, other conservation groups, um, and, uh, and then they go and either live their lives elsewhere or sometimes, um, a, a place that is interested in killing them for the meat will also buy them.

Ariana Brocious: If you could share, I don't know how your experience differed from that of your grandparents or your great aunt. Did they have more memory of interacting with bison on the landscape in a less kind of controlled manner?

Rosalyn LaPier: No, I mean, they had a similar experience that I did. you know, the bison stopped being part of Blackfeet landscape in about the 1880s. So, by the time that my grandmother and her aunts, um, were born, they had already been on the reservation for 20 to 25 years. So, almost an entire generation, like, By the time my grandmother was born, had lived on the reservation, um, and were kind of confined to the reservation, uh, since the demise of, um, the bison population numbers. Maybe that first older generation they did remember, you know, bison out on the prairies and they did remember what is now Montana as a place with no fences, you know, no ranching, no farming the way we see it today. No agriculture. But as the generations Um, came along, um, there was less and less, uh, interaction with bison as an animal, but not bison again as part of religion or religious practice or part of our mythologies.

Ariana Brocious: So I'd like to talk a bit about the interconnection between indigenous people of the plains, particularly the Great Plains, and then this species that, you know, had at its height millions and millions of animals roaming this landscape. In the Ken Burns documentary, The American Buffalo, which you are, um, uh, a guest on, Germaine White lays out this timeline.

Germaine White: When the buffalo are here, the land is good. When the land is good, the buffalo are healthy. We have lived here for 600 generations. We have been here, conservatively, 12,000 years. So if you think about that 12,000 years and and imagine that on a timeline, and then take that 12,000 years and wrap that timeline around a 24-hour clock, what that means is that Columbus arrived at about 11:28 p.m. and Lewis and Clark at about 15 minutes before midnight.

Ariana Brocious: What is it, what do you think about hearing that clip about the longevity of this relationship?

Rosalyn LaPier: Well, I think it's something that indigenous people know, you know, indigenous people recognize that they have been here for thousands of years, that they have relationships not only with bison, but also with other animal species and with You know, the plant world as well, that over time that we've established these long term relationships, um, with the animals and with the plant world, um, that through, you know, observation and utility, that we really know these animal and plant species. And so we recognize. That, for indigenous people, it was a really short time that bison have not been part of our lives, that this kind of reestablishment and restoration of bison back onto, uh, the landscape Is sort of a short hiccup,

Ariana Brocious: And how did bison in particular evolve with, co evolve really with indigenous people? And that relationship involved hunting and, you know, eating animals as well as, as reavering them, like you're saying in traditions, in cultural ceremonies and so forth.

Rosalyn LaPier: So, yeah, the way we would define bison today on the Great Plains is we would define them as a keystone species, right? So a keystone species doesn't necessarily need to be the largest. In this case, it is quite, they are quite large. It doesn't have to be the largest species, um, within an ecosystem, but it needs to be kind of the most important animal or plant within an ecosystem so that when you pull that particular animal out of that ecosystem, that sort of there's this cascading effect, almost like dominoes falling, right, of how the ecosystem does not work or function as well as it could anymore because that keystone is gone.

Ariana Brocious: And I'd like to dig into the ecology a bit more with you, cause I know this is, I find this really interesting. So, as you said, bison are big animals. There were millions of them. They move a lot across the land. They eat lots of different things. Their hooves break up the soil. They fertilize it as they, you know, leave poop behind. I've even read that maybe the presence of bison is why the Great Plains was almost treeless because they essentially prohibited it at the time of the peak of their numbers, the trees couldn't really establish. Is that true?

Rosalyn LaPier: Yeah. So you need to think about, you know, the Great Plains as one, a large, it's one of the largest eco regions in the world. It's an area that is primarily, uh, grasses, um, either short grass prairies, It's an area that, um, now is one of the most threatened ecosystems in the world, because they're also the same places that we conduct our agriculture, right? So most of the areas today that were healthy prairies in the past are now places where we grow wheat, where we grow barley, where we grow corn, um, so they, these, they've kind of flipped over from sort of these healthy mixed grasses to, in some cases, kind of mono, uh, mono, uh, culture systems of, of one type of grass, like wheat or barley. So bison, because there were millions of them in the past, um, you have to think of sort of this wide open prairie area, again, with lots of different grasses, that is being disturbed on a regular basis. it's being trampled, it's being eaten, it's being rolled around in where bison create wallows, and all of this disturbance. is what creates the prairies. And all of this disturbance is what is beneficial to the prairies. And it's beneficial to other animals. It's beneficial to the bird, to birds. It's beneficial to plants and it's beneficial to humans as well. There are certain plant species that love disturbance, and that's where they grow. And so when the bison would disturb a particular area, either by walking through it or trampling through it or rolling around in it, then certain plants would grow in those areas. Indigenous people learned this over time and learned that in particular areas, those were the places where you could collect particular medicines or particular kinds of food. And so they wanted the bison to be in particular areas to disturb those areas so that then they could go back and collect food and collect medicine. And then they wouldn't have to, you know, kind of the stereotype often, That people say about indigenous people is that indigenous people, you know, went, quote, unquote, I'm you doing air quotes, air quote, searching for these things. Often they knew exactly where to find them, right? They knew exactly where these plant medicines were because they knew where the bison were.

Ariana Brocious: Right. And what do we know about the role that these bison played in carbon sequestration pre sort of European settlement?

Rosalyn LaPier: Anybody who's mowed a lawn knows that grass grows from the bottom up. So the more you mow your, it's kind of a catch 22, right? The more you mow your lawn, the more, the more your grass grows. This is something that indigenous people knew thousands of years ago that bison were doing. So what's different about prairie grasses is that prairie grasses have really, really deep roots. Sometimes their roots can be, you know, 6, 8, 10, 12 feet deep into the soil. And this makes for extremely healthy soils on the Great Plains. The bison never over harvested, um, grass. They would just move on. They would just, they'd eat grass and then they'd move off, off to the next place and eat some more grass. And because they were eating different kinds of grass in different seasons, then they were able never to overharvest one particular kind of grass. Because of that, the soils on the Northern Great Plains were some of the healthiest soils on earth before contact and before modern farming and modern agriculture.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. Coming up, the parallel mindset between destruction of the bison and the destruction of our climate:

Rosalyn LaPier: We need to think about how our actions really impact the entire natural world. And I think we have seen numerous examples in the past where we have had this belief system that we are living in a world of abundance, and we don't live in a world of abundance. You know, it is a finite world.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. We’ll hear more from Rosalyn LaPier later in the show. Let’s return to Greg’s conversation with documentary filmmaker Ken Burns.

Greg Dalton: Well, you talk about your characters, people in your films evolve and it sounds like you have to, from the West to National Parks. National Parks was criticized for marginalizing some of the indigenous characters. And it's you said. You're glad you waited to make the Buffalo, cuz you yielded –

Ken Burns: I would disagree. I would disagree with that, criticized. I haven't heard any mean we were in editing and we realized that we needed not to just go back to the very beginnings for the geological forces that created a particular park, but understand from the very beginning with Yosemite, who was being pushed aside in order for that park to be discovered by white people. And so that was all throughout. We, I think we'd learned not even a lesson. It was always been our case. In fact, our history of the West ceded all the stuff about gunfighters and the legends and the Bat Mastersons and all that stuff in favor of telling a narrative that included the central, centralizing, you know, the West was the West for white Americans. It was the South for British and French. It was the. East for Russians and Chinese. It was the north for Spanish, but it was home, principally home for native peoples. And so that's, it's always been part of our message. I felt that by, when we talked even before that film was out about doing a standalone film on the Buffalo and each time we, it just carried along. I think what we were able to do was not change our modus operandi, but just benefit from new scholarship and the ability, as I said at the beginning of our conversation, to sort of cede, um, the kind of agency of the narrative to, to people who have much greater experience with it.

Greg Dalton: So Brenda Child, as an Ojibwe scholar, wrote in the journal Public Historian that the National Parks documentary, quote, almost entirely erases Indigenous history from the landscape.

Ken Burns: I don't know what film she watched, uh, cause we didn't start a description of any park without talking about the original inhabitants and their throughout and their Native American voices and Native American interviews, uh, throughout. So I'm, I'm not sure she saw the same film we made.

Greg Dalton: One of your next films as a large project on the American revolution. That's typically a story driven by white landowning men. It's a 12 hour series that promises to include so called ordinary people who waged and witnessed war. How are you approaching the people featured in the relationship to the land?

Ken Burns: Yeah, it's pretty complicated. Uh, the first quote is from a Native American who basically says, we know you know how valuable our land is. We know you want that. We know you're coming to take it. It does the whole thing. We put it in the perspective of that. The losers of the American Revolution are without a doubt, number one, the Native Americans. Number two, obviously the Black Americans who are, despite the fact that we've proclaimed universal rights of all human beings, remain in bondage. And then you can go down the list of who, you know, who also, you know, the Spanish and the French lost, uh, you know, even though they had helped us, the Brits actually, you know, lost, but gained the trading partner, which they wanted to have. And of course it were the white Americans who were then felt free to o’er spread the continent for our yearly multiplying millions manifest destiny. It's complicated story and it's, it's hugely important and filled with authentic, um, Native American music and voices and African and German and, you know, Scottish and Welsh and Loyalist and Patriot and it's women and it's very, very complicated story. I know, I don't know if I've, I've grabbed a sort of bigger tiger by the tail.

Greg Dalton: It is a complicated history, but how important is it to you that Americans have a shared understanding of this country's history? That seems to be a lot of part of our toxic political culture these days is whether we're ashamed of our story. If somehow, if you're self critical, then you're ashamed. But you seem to be –

Ken Burns: You just tell a good story. You know, you get involved in the politics, you know, back and forth. You kind of get stuck in that false binary positions and it makes it hard. It just becomes an argument. But if you tell a story, you're obligated to tell everybody's story. And when you do, you've got a complicated thing. We made a film on Vietnam, which we thought people would be so controversial. We had to create a war room, you know, of Democratic and Republican operatives who would know how to answer each thing. The cobwebs grew over them. Right. I mean, just, it was, it was so interesting. I'm not sure that will happen with the American Revolution since, you know, as we approach the 250th, people are going to be pretty, pretty staunch about their own beliefs, but They all can coexist. I mean, there's some, there is an aspect of filmmaking, which is superficial, say, compared to a textbook. At the same time, there's something that is able to, to contain a multiplicity narrative can have a multiplicity of views and, and let them coexist. So it's not, we're not like, uh, copping out of, of judgment. We're just saying, this is what some person believed. This is another, it's very, very obvious, uh, a higher morality. But that's the genius of storytelling. That's where change can actually happen, when you tell, tell a good story.

Greg Dalton: And this story of the American bison is, you know, intentional extinction, almost extinction, and then it's a story of kind of resilience and, and perhaps even more opportunity in the future. If the bison is a bit of a part of the climate story of extraction and greed that we've been talking about, how do you think about that with respect to climate change?

Ken Burns: Yeah, no, I think it's really important. Another film that this same team worked on was a history of the Dust Bowl, which is, people don't remember. Was the largest man made ecological disaster in the history of the world until climate change. And it was man made people forget that it was the tearing up of the buffalo grasses of the prairie and planting crops that did it. And it wasn't, you know, two or three storms, you know, it was 10 or 15 or 20 storms a year for 10 years. It was devastating. It not only killed your crops, it killed your cattle and your children. And I think the accelerating reality of climate change gives us an opportunity to make some very stark and very clear and very definitive stances. Yes, I wish to be part of the solution. I wish to be part of an immediate response because if there is not immediate response, we will be fiddling while Rome burns. And that is not an option. I am a grandfather, you know, I need them to inherit an earth that I know, and it's getting warmer and it's getting more unpredictable and it is a much more fraught situation and, and is, you know, as the a thing goes. Now is the time for all good people to come to the aid of their world.

Greg Dalton: Well, Ken Burns, thank you so much for sharing your story and your entire career. It's a real honor to talk to you.

Ken Burns: It's my pleasure. Thank you.

Greg Dalton: Ken Burns’s latest documentary, “The American Buffalo” debuts on PBS stations around the country this week. Now let’s return to Ariana’s conversation with Indigenous environmental historian and ethnobotanist Rosalyn LaPier, discussing the impact of the bison on the Great Plains ecosystem before the arrival of white settlers.

Ariana Brocious: How does the story of the bison parallel the story of indigenous people on the plains and in what's today the Western U.S.?

Rosalyn LaPier: Well, I'm, I'm not sure to what extent it does only because I'll just say because, uh, bison are animals and humans are humans. I mean, there was an effort, um, by the United States government that's been documented and it's in the, it's, it's discussed in the film, um, how the United States government did attempt to, um, to kill most of the bison, um, and built and bison can't fight back, right? Bison aren't humans. They can't fight back. They need humans to do that for them. Native Americans also at the same sort of time period. were under a process of both genocide and cultural genocide that the United States government inflicted upon Native American communities. Um, and the difference is, Natives fought back, and they fought back, um, in a multitude of ways, and, uh, continued to, both sort of fight and also work with the federal government to address the policies that the federal government was inflicting upon Natives, and to change those policies. So over time, and it took a long time, but over time, the federal government has changed its policy, for example, of cultural genocide of Native American children, so that that's not a policy anymore. I think one of the things that Native people have learned over the past 100 plus years and what happened with Bison and with their own personal story is that the, the potential always exists for the federal government to change their policy. The potential always exists for the pendulum to swing in the other direction. So right now we're in a, in a time period of self determination for indigenous people, but also restoring the bison and restoring grasslands on the northern Great Plains, that are part of the ecosystem that bison use. But the pendulum can swing in the other direction where funding gets taken away and the federal government decides that these are, they're going to change their policies. And so as one elder has expressed to me numerous times is, you know, native people have to be eternally vigilant to watch. How federal policy is moving so that we can step in and, um, address those things before they begin to happen and before the pendulum swings the other direction.

Ariana Brocious: In the film, you ask why destruction is so much a part of the American story. How do you answer that question?

Rosalyn LaPier: I think that's a hard question for me to answer because in the film, you know, I was really, I was referring to both, you know, Americans who are part of the settler colonial community, but I was also referring to everybody, you know, including native people that we need to think about how our actions really impact, um, the entire, uh, natural world. And I think we have seen numerous examples in the past, where we have had this belief system that we are living in a world of abundance and we don't live in a world of abundance. You know, it is a finite world. And we're kind of seeing this behavior a little bit right now as well with climate change, in that certain people think that we're living in a place of abundance, and that there's sort of not an end in sight, in terms of water usage, or food, um, etc. Or fossil fuels. So that, so that the idea that we, live in this abundant world. Um, we do to a certain extent, but to a large extent, we don't. And there's always an end in sight. And I think that people in the 19th century, um, behaved as though there was no end in sight. And so we saw numerous extinctions of animals from the United States during the 19th century. Um, and bison was almost one of them, um, because of that belief of we could just, you know, continue to, um, kill them and continue to impact their habitats, and they would still be there. So I think that that's something that,today, I think younger generations are beginning to question, and ask, uh, people from, you know, older generations to really slow down and think about how we are living in a finite world.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, there are very clear climate parallels, as you said,There are now over 350, 000 American buffalo, but only about 20, 000 of those are under indigenous or native management. An article in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution in January 22 examined the potential for bison being restored by tribal nations on the Great Plains and the benefits this would offer in an increasingly unstable climate future for indigenous peoples, themselves as a food source, especially on places that might be kind of food deserts, but also as we've been discussing how resilient bison are, as a member, as a cornerstone piece of this plains ecosystem and restoring the health of the great plains as well. What do you think needs to happen to help tribes who want to bring the bison back in this manner?

Rosalyn LaPier: Well, one of the things that we do know about bison is that they need large pieces of land to live on. So one of the things that People can do is work With tribes and tribal communities to return as much land as can be returned to tribal communities so that tribes can then have bison on that land. We know that the vast majority of bison in the United States right now are confined. There are no free roaming bison in the United States. They're all confined either behind fences or behind borders. Um, and so we, one, we don't know. the true kind of ecology, um, or ecological systems that bison impact because we haven't been able to study them, um, in the 21st century or the 20th century. What we do know, we have learned from very small areas like Yellowstone, there's been a lot of scientific research done in Yellowstone, but Yellowstone's not that big of an area. and the bison there are not allowed to leave, right? There's a border around them. So as indigenous communities are beginning to return bison to their own landscapes, one of the things that we need to think about is how to enlarge indigenous community landscapes, how to enlarge reservations, how to enlarge their land so that they can have bison that are free roaming bison, if they want that to be the case, or very large areas where bison can live, and live in a healthy way with the ecosystem that is in that particular area.

Ariana Brocious: Rosalyn LaPier is an indigenous environmental historian and ethnobotanist. Thank you so much for joining us on Climate One. Thank you.

Greg Dalton: Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe wherever you get your pods.

Talking about climate can be hard-- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Ariana Brocious is co-host, editor and producer. Austin Colón is producer and editor. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Wency Shaida is our development manager, Ben Testani is our communications manager. Our theme music was composed by George Young (and arranged by Matt Willcox). Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.