Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton, and today in Climate One, we’re discussing impact of meat production on our health, our economy and our climate. Many people associate climate disruption with smoke stacks and tail pipes belching dark clouds but belching cows may be just as bad. United Nations report titled the Livestock’s Long Shadow found that animals account for nearly 20% of all greenhouse gases.

Another estimate by experts from the World Bank say, cows, pigs and other animals cause half of the world’s carbon pollution that is driving severe weather. What’s that mean? Producing a half pound hamburger can generate as much carbon pollution as driving a 3,000 pound car ten miles and if you’re driving and eating that hamburger at the same time. Over the next hour, we’ll look at how meat is produced. The growth of organic and grass-fed beef, the impact of California’s drought on the livestock industry, the new farm bill and much more.

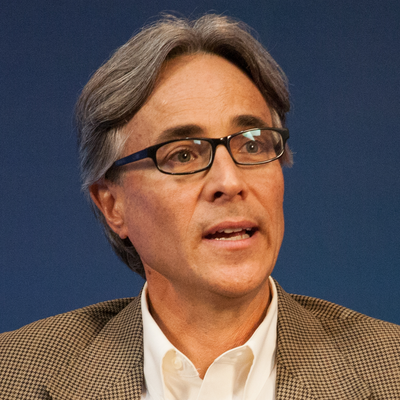

Joining our conversation here today at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, we’re pleased to have with us two people on opposite sides of the steer.

Tim Koopmann is President of the California Cattlemen’s Association. His family has been ranching at Alameda County for nearly a century. And Dave Simon, is author of

Meatonomics: How the Rigged Economics of Meat and Dairy Make You Consume Too Much and How to Eat Better, Live Longer, and Spend Smarter. Please welcome them to Climate One.

[Applause]

And I want to ask you, you’re family has been at ranching a long time. So I guess you didn’t have much choice but tell us a little bit about your background and how you came into ranching?

Tim Koopmann: Well, I certainly did have a choice but I chose and my kids have both chosen to stay with the lifestyle that we love and the heritage that we love in nurturing a land and nurturing livestock and enjoying what we do and having a land ethic.

My great grandparents came from Italy and Germany 1868, landed in Half Moon Bay and sharecrop their way into the Dublin Area. And my grandfather and great uncle purchased the ranch that we now still live on in 1918. It’s a family operation. It has continued on through multiple generations. I’m the first of four generations that has an outside source of income or an off-ranch income because of the economy’s scale of our particular operation.

We run about 200 mother cows during normal years. Of course this drought year has been somewhat challenging to say the least. And we’re down about half the numbers but we’ve enjoyed the lifestyle, we think we are doing a good job of stewarding the land and taking care of it. We own about 850 acres in total with the home ranch there.

We lease another – almost 1,800 acres of additional land that we ran cattle on as well.

Greg Dalton: David Simon, tell us how you came to write the book

Meatonomics.

David Robinson Simon: So, several years ago I sent an email to a bunch of friends that had a link in it to a video about factory farming practices. And I know that Tim does not run a factory farm but most of our meat comes from factory farms. And the responses that I got to this email were sort of across the board. But the one that really stuck out for me was a response from a friend who is a Dean of a major law school who wrote back that while he thought that these factory farming practices were disturbing and distressing, in his view they were illegal. And that meant that they were an exception or an anomaly.

And at the time, although I’m a lawyer, I didn’t know whether he was right or not. I didn’t know how the law applied to farm animals. But I decided to do a little research and what I learned really shocked me. And that is that over the last several decades in this country, large animal food producers have embarked on a very aggressive legislative campaign to emasculate and eliminate virtually all anti-cruelty protections that once applied to farm animals.

So what we’ve seen the last several decades is that literally, anti-cruelty protections that once protected farm animals from abusive behavior have simply been eliminated in virtually every state in this country. That’s not it, in addition, large animal food producers and I’m not talking about Tim, talking about large corporate animal producers that have a very significant influence in congress, have been successful in many states and in congress in passing the laws that make it difficult for consumers to sue them, to investigate them and in fact to even criticize them.

These laws, this huge framework of legal protection does not help animals and does not help consumers, it helps only one group, animal food producers. And it helps them by providing them a very valuable economic benefits, allows them to sell their products at lower prices to make more profits and to sell more of those products.

Tim Koopmann: It’s disturbing for us as livestock producers to have this perception that production basically lives on the backs of animals that are abused from the time they’re born until the time they’re slaughtered. Mainstream producers, and I represent as a California Cattlemen’s Association president, we have about 3,000 members and I can honestly say that our membership is very cognizant of and very aware of beef quality, beef treatment, animal treatment, all the good things that go along with the nurturing of these animals.

Temple Grandin recognized an issue quite some time ago. And I’ve heard her speak several times and I had the opportunity to have dinner with her one time. And it’s unfortunate that she’s had to do what she’s done but it’s good that she’s made people aware that some of our practices in the past perhaps did not provide the proper care. But I think that from the mainstream, those of us that are involved in the industry are treating our animals with the utmost professionalism. And we care about what we’re doing. We end up in the middle of the night nurturing a baby calf, trying to get him born, we raise bottle-calves if mom has a problem.

We’re doing the right thing. And when we have issues like the Hallmark case which was a couple years back where we see the cruelty and it is absolute cruelty the way these animals sometimes are treated. It’s a black eye for all of us that are doing things right. And we will fight against the mistreatment of animals just as much as David or anybody else would.

Greg Dalton: But isn’t it true that there have been laws passed that prevent video in meat-processing plants, that sort of thing and there’s what they call hamburger libel laws that certain things Oprah famously, you know, got involved in that in Texas. So hasn’t there been some legal protections around the industry that sort of prevents transparency?

Tim Koopmann.

David Robinson Simon: I can answer that.

Greg Dalton: Okay.

Greg Dalton: Okay, Simon.

David Robinson Simon: Yes. I mean you’re talking about exactly the legal issues that I’m concerned about. Ag-gag laws, many people have heard about. These are laws that are passed in seven states in this country now and that producers continue to try to pass, we’re only in the eighth week of this year, already four new ag-gag laws have been introduced. These are laws that criminalize undercover investigations at factory farms by making it illegal to lie on a job application or illegal to take film or video. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg, you also mentioned cheeseburger laws, these are laws that say a plaintiff can’t sue a food producer or retailer over claims that the plaintiff developed an obesity-related disease. We have eco-terrorism laws that provide enhance criminal penalties for people who engage in relatively innocuous crimes, when those crimes are targeted in animal enterprise.

So if you engage in vandalism down to 7-11, you might get a ticket. You might get cited for an infraction. But if you engage in vandalism at a factory farm or like even a grocery store or restaurant where animal products are sold, you might be cited or you might be charged with a felony.

Just because of these enhance criminal penalties. So there’s fairly broad range of protections that producers have put in place.

Greg Dalton: I’m going to get

Tim Koopmann on that but first, I mean if I eat a bunch of cheeseburgers and get fat, why should I be able to sue McDonald’s or someone else? I mean at some point, there’s got to be some personal responsibility in this.

David Robinson Simon: There does, but as many people may be aware, the tobacco industry for decades misled Americans about the effects of tobacco smoking. And when lawsuits were finally successful, tobacco companies were forced to pay more than $400 billion to state Medicaid programs in this country. And many people are concerned that large food producers are misleading consumers as well. And the consumers are being literally denied the ability to make informed choices about what to eat. And at some point, I completely agree with you, we need to make personal decisions and take responsibility, but if you’re given false and misleading information which is what the tobacco companies did, and which is why many people think the food companies are doing, then that changes the playing field.

Greg Dalton: Well, tobacco’s addictive in a way than meat perhaps isn’t. But

Tim Koopmann, do you want to respond to this?

Tim Koopmann: Well, I just like to respond a little bit to the ag-gag laws. California Cattlemen’s Association did propose and worked with the state legislator last year to have our own animal protection law drafted. And we, I will not call it an ag-gag law, the only thing that ours did, and we promoted it and HSUS was successful in kind of damning it and saying what it wasn’t. We wanted to have – the only thing in our bill included was that within a 48-hour period, any observed mistreatment of animals that you had to turn that evidence in to a law enforcement officer within 48 hours. There was no penalty for any of the things that were mentioned previously, falsifying applications, et cetera.

We want to stop any instances of animal cruelty because it’s a black eye for us most definitely. We don’t want those people in business and our ag-gag bill if you would want to call it that, all it did was impose a rule that said within 48 hours of the observation, there’s misbehavior, that needs to be turn in to law enforcement.

Those that called it an ag-gag bill, why did you want to hold on to that for 48 hours? Why did you want to hold on to it for two or three or five weeks if you could stop the cruelty that was going on in a particular location, why didn’t you do it? And that was what our bill was about.

Greg Dalton: How about some recent laws regarding that the confinement of livestock in California, there has been some, that’s less on cattle, perhaps more on pigs and poultry that sort of thing.

Tim Koopmann, is that something that is fair game to have some laws about the confinement of animals?

Tim Koopmann: Well, this is not an area that I have much familiarity with. When we look at happy cows in California if you will, I got to say that my little gals at home are pretty damn happy. My cows, as long as they’re having a baby every year, we sell the calves as our product and the cows stay there and they’re on pasture 365 days a year and they’re fed hay. In the winter time when it gets cold, they’re moved from pasture to pasture, the rotation system so they always got some feed in front of them and they’re doing well. And I would enjoy having anybody here come out and make a ranch visit.

As far as the confinement issues with poultry, pigs et cetera, that’s kind of out of my area of expertise.

Greg Dalton: But there are also concentrated factory farms in California in the central valley where the small sort of pastoral image of a rancher might be one thing but there’s industrial feedlots where it’s a whole different story. And that’s I think part of the thing that –

Tim Koopmann: If I could maybe address that. Probably everybody has been down Highway 5 and observed Harris Feeding Company and seen the feedlot situation there. When I sell my calves, they generally go to another six-month period of time - they wean off the cows at about 700 pounds, they go to another grass season of six months then they will go to a feed yard, concentrated feed yard if you will, CAFO, Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation. And they’ll be fed for a 120 to 150 days on a grain ration and from there, they go for processing. If you go by the Harris Feeding Company or any other feedlot, there is adequate room and space. There are shade structures, there is a sprinkler system in place and I think that’s a little different than some other animal species in terms of the confinement.

The animals in the feed yard have plenty of room to roam around and scientists have determined how much square footage of space, bunk space and loafing space that need to be there. And that’s for about 120 to 150 days is when those cattle are in that confinement period.

David Robinson Simon: I’m happy to say that this is one area where you and I agree completely. I think that first of all, your operation is great I think it’s great that your animals are not confined and have the ability to roam. But I also think that in general, beef cattle are known to have sort of the best lives of all the animals that people raise for food. However, let’s look at chickens because chickens represent the majority of the food that Americans eat both by virtue of the number of animals and by virtue of the amount of pounds that we eat per year. Chickens lead terrible lives, they have their beaks cut, they’re debeaked so they don’t attack each other, they’re closely confined, they’ve been genetically manipulated to the point that they can’t walk and beef is certainly one thing but that trepresents about 30 % of the American diet.

We need to look at chickens, we need to look at pigs, we need to look at egg production for example. The hens who lay our eggs are raised in battery cages, a typical hen has about 65 square inches to spend her entire life in. That’s a space about like this. She can’t open her wings. Typically if you look at battery cages, you’ll see one hen on top of another one. This is where all of our eggs come from except for cage-free eggs that represent less than 5% of the eggs we consume in this country.

Greg Dalton: Let’s talk about the climate impacts of this. We started out talking about the livestock could be as much as half, somewhere between 20, 50% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Tim Koopmann, what do you think about the connection between livestock, methane emissions and climate change?

Tim Koopmann: Firstly, I’d like to challenge one of the statistics that was thrown up on the screen here earlier. The UN’s publication Livestock’s Long Shadow cited that 18% of all greenhouse gases I think United States production of greenhouse gases could be attributed to the livestock industry. And since that time there’s been a correction done by the scientific community after being challenged and they weren’t comparing apples to oranges. And I think it got lower down to about 3.1% And so, if the livestock industry is at 3.1% that certainly is miniscule compared to the transportation industry, the energy industry et cetera. So that 18% figure I believe has been discounted.

Greg Dalton: Well, there’s been some different numbers it depends on who’s counting and they’re counting methane as much more powerful than carbon dioxide, dairy cows, beef cows are a big source of methane, is that something that the California Cattlemen recognize?

Tim Koopmann: Absolutely. It has been of interest certainly when the U.N. paper came out, it prompted our industry, our business if you will to take a look at methane as an offshoot of livestock industry, both dairy and beef.

And I know that at UC Davis, there’s a professor and a scientist that’s been working on the application of methane digesters. Where some of the methane gas that’s coming off a dairy operations where you got confinement cattle can then go into producing the energy to run the dairy. So it is of concern, we’ve looked at the numbers and there is work being done by our folks.

David Robinson Simon: Well, by virtue of the way I feel about this I tend to favour the studies that show a higher connection. And as you mentioned Goodland and Anhang published a paper that said that animals reproduction is responsible for 51% of climate change and I think that probably the –

Greg Dalton: These are former – these are experts that worked for the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation.

David Robinson Simon: That’s correct, a couple of scientists. And while 51% sounds pretty extreme, I think many people except the U.N. estimate 18% as a fairly conservative estimate but, you know, the methane issue is an interesting one. Because as you mentioned, methane is 21 times more effective at trapping heat in our atmosphere than carbon dioxide. And with respect to cattle who are raised organically and fed on grass, which is nice, the unfortunate result is that they produce four times as much methane as grain-fed animals and so we get this very bizarre result that organically-fed cattle are not necessarily more eco-friendly than inorganically raised animals.

Greg Dalton: You just bummed out a lot of people in Berkeley and Marin. So okay, so because a lot of people are very upset about feeding grains to cattle, saying that’s not good because it competes with food, rise of food prices in developing countries.

So

Tim Koopmann, let’s have your response to that. Organic cows are not green, they’re just okay.

Tim Koopmann: Well, I’d also say that through genetic improvement over the past 30 to 40 years, we have fewer cows in California, we have fewer cows in the United States. Because the efficiency and the genetic improvement and this is not GMO, this is genetics simply taking a bull that’s got some value to him and using him more frequently and using him through AI. We’ve got fewer mother cows in the United States today than we’ve had since 1951. I think we’re at 89 million cows in the United States presently, with about 6 million or 5 and a half million in California. But that’s a whole lot less than used to be around, so if you got fewer cows belching and passing gas, if you will, I think the efficiency of the cows that we’ve got has reduced that number. And I think we’re working to reduce numbers further to get more efficient production and when we’ve got fewer cows, probably less gas.

Greg Dalton: So just to clarify this, a cow that’s grazing on grass is going to chew and burp more methane than a cow that’s sort of eating –

Greg Dalton: – corn out of a – okay.

Tim Koopmann: There’s a little difference between organic and grass-fed as well. We can have grass-fed finishing but organic beef, organic products in general have to meet some very rigorous standards that are established by USDA. Grass-fed beef does not have to necessarily be organic, and natural beef can be just free of antibiotics and free of hormones. So there are different classifications of the product.

Greg Dalton: And organic and grass-fed, are those growing segments of the market? Give us a sense of the scale of it.

Tim Koopmann: Absolutely. There’s a growing -and I’m through calling it niche marketing at this point in time, because I think that as consumers, lot of us like have accepted the fact that we want a natural product, no hormones, no antibiotics.

We want a grass-fed product which doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s organic but we prefer the taste, we prefer the fact that we know where that animal came from, we got a little history on it. So it is not necessarily a big part of the market now but I think it’s a growing segment of our market and we accept that and we’ll work accordingly.

Greg Dalton: David Simon, some research says that if what you eat is more important than what you drive, the fastest way to address climate change is to reduce meat consumption. That’s even faster than moving to alternative fuels which we spent a lot of time here at Climate One talking about.

David Robinson Simon: That’s true. I remember a study that said that going vegan has the same effect as switching from a gas hog to a Prius. And it’s not just climate change that’s an issue. There are many other resource issues. The resources required to raise animal food, remember we’re not just talking about beef, beef represents a small portion of the animal foods consumed in this country. You’ve got to think about chicken, pork, dairy, egg, et cetera. [mic noise] It takes on average, five times as much land to produce animal protein as it does plant protein. It takes 11 times the fossil fuels and it takes 40 times or more water to produce animal protein than plant protein. So we are seeing a collision between increasing demand for these products and dwindling supply of the scarce natural resources necessary to produce them. And that’s a major sustainability problem.

Greg Dalton: Tim Koopmann, the energy comes from the sun to plants to humans, but if it goes from the sun to plants to cows to humans, there’s an extra step in there, it’s an inefficient way to translate some energy into our bodies.

Tim Koopmann: With two-thirds of the United States being non-arable, in other words we cannot farm it because of topography and soil conditions and soil depth, I believe strongly that the use of beef cattle as a grazing tool on these rangelands that we’ve got is a good way to produce a really valuable, highly nutritious and safe protein source for the world. Two-thirds of the United States are not farmable and we were able to produce a beef product there on the grazing land or the rangeland. And I think in the absence of grazing that land, in the absence of beef as a protein source, just replace that to the world, we would have to have more farmland, we would have to use more resources for farming to produce legumes and beans and all those things that can be used on a vegetarian or vegan diet to replace a meat product. And we don’t have that farmland available to us. We’ve got an increasing population in the United States. We got an increasing world population with huge demand for protein as a part of their diet. And on the absence of grazing livestock and having that land available to produce food I think we would be in a lot worse shape than we are and we’d be in trouble.

Greg Dalton: David Robinson.

David Robinson Simon: Well, we use the majority of our cropland in this country to raise feed crops to feed to animals. And a great study that came out about 20 years ago suggested that almost 1 billion malnourished people on this planet could be fed if the feed that we give to animals was instead fed to people. So I think we disagree a bit on whether we’re using our cropland effectively in this country.

Tim Koopmann: I think that where the problem lies is in the logistics and the mechanics of getting feed or food crops that are fed to cattle delivered to where it’s needed. I don’t have an answer for that, where is the infrastructure, how do we get it there and how do we get it distributed adequately it’s fairly for those that are malnourished.

Greg Dalton: Were cows intended to eat corn?

Tim Koopmann: Corn is not a staple food of their diet. No, it is not.

Greg Dalton: Why is it used?

Tim Koopmann: It is used because it produces a white fat, and it produces the marbling within the muscle tissue itself that’s become desirable. It helps the tenderness, the quality and the flavor of the meat.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about meat and climate change today at Climate One.

Tim Koopmann, is President of the California Cattlemen’s Association and Dave Robinson is the author of the book

Meatonomics. And Dave Robinson, on

Meatonomics, let’s talk about subsidies. You write a lot about the subsidies that go into ranching and farming and we just passed a farm bill, so let’s talk about the economic side of this.

David Robinson Simon: Well, I calculate in my book the total subsidies that state governments and the federal government provide to animal agriculture each year in this country. And I calculate that number at about $38 billion. To put that in perspective that’s about half of what all states spent on unemployment benefits last year. That number is probably an order of magnitude higher than the number that people typically think about when they think about animal food production subsidies but that’s because as I mentioned in this country, we devote more than half of our land to raising feed crops and we subsidize feed crops heavily. So producers benefit from those subsidies. When we calculate subsidies to animal foods, we have to calculate, have to include subsidies to feed crops. That includes not just things like crop insurance but irrigation subsidies as well that are provided at the state and federal level.

Greg Dalton: Tim Koopmann, there’s a lot of – maybe you don’t directly benefit from those subsidies but there’s a lot of subsidy that goes into growing food for animals.

Tim Koopmann: I think the recently passed new farm bill has either reduced or eliminated direct cash subsidies to most farming operations. It's something that we in the livestock industry have been targeting for quite some time. I personally have not availed myself of direct subsidies of any kind because the livestock industry doesn't have those available to us. But I do know that the midwest, where the bulk of our green crops are grown, have successfully had these subsidies delivered to them for many, many years. Very strong political base there. And I think that it's been a desire of a lot of folks that those direct payments be done away with and I think what's available in the new farm bill is primarily crop failure insurance or crop insurance and price insurance, and not the direct payments that we've had in the past.

The livestock industry has always been kind of independent. As a matter of fact, I grew up with – my grandfather and my dad telling me that, "Don't sign up for any of those programs. It's cowboy welfare." And so I have avoided even doing things like that too much.

Greg Dalton: I think you're in a minority there. But, Dave Simon, is the recent farm bill a step in the right direction?

David Robinson Simon: Tim is correct that the farm bill eliminates direct payments and I think those were something that people found incredibly objectionable. We had situations where people like Scottie Pippen, an NBA star, was collecting subsidies for land that was once used for farming. But I think – this might be another area where Tim and I differ a little, from what I understand about your ranch, Tim, I think that while you didn't – while you haven't accepted direct payments, I think, if I'm correct, you've accepted at least three forms of what might be considered indirect subsidy. So you've got Grassland Reserve Program, you've got the EQIP Program and you've got conservation easements.

Now, the Farm Bill continues programs like that, they cost taxpayers money and, while direct payments are the most objectionable, this stuff all costs us money. Crop insurance will probably cost us $20 billion this year.

Tim Koopmann: First of all, let me address the easement that you mentioned. Yes, I do have two conservation easements where, actually, they were mitigation easements on the family ranch. The funding for those mitigation easements was not from the government. The funding for those mitigation easements – first of all, the first one was for the preservation of a breeding pond for the California Tiger Salamander, and that was through mitigation for a San Jose housing project. And the developer of that housing project was going to disrupt 15 acres of prime California Tiger Salamander habitat and in order to get his permits from the U.S. Fish and Wildfire Service Corps of Engineers, California State Department of Fish and Wildlife, he was required to replace the habitat value that he was destroying in perpetuity in another location. I happen to have had this breeding pond for many years and I knew we had the Tiger Salamanders in there, because I used to take them home in a shoebox when I was a kid. But that’s – nobody here from Fish and Wildlife, is there? Anyway, we were able to merchandise the sale of a conservation easement or a mitigation easement for that breeding pond for the CTS. So that was paid for by this developer in San Jose.

The second easement that we have was for the construction of a golf course in my north border and so that was mitigation for the golf course itself. We have violas or a wildflower Johnny Jump-up sister, people commonly call them, and they play an integral role in the lifecycle of the Callippe Silverspot Butterfly which is another ESA or endangered species.

And so because we have this wildflower population every year that provides this habitat, the golf course folks – the developers of the golf course had to replace habitat that was being lost for the golf course and we were able to provide that.

In the EQIP now – David has mentioned the EQIP Program, Environmental Quality Incentive Program, that's through the Natural Resource Conservation Service which is an agent or a sub-agency of the USDA and funds are made available to ranchers and farmers for doing conservation practices on their land that benefit all natural resources. And, yes, I have taken advantage of that, but the thing about these grants from USDA, they're usually a 50% funding source. In other words, out of my pocket comes 50% of the cash needed to restore a creek, fence out a riparian area and do those things that are helping conservation and 50% comes from the grant program through the USDA or the Environmental Quality Incentives Program.

I think that most farmers and ranchers are providing what we commonly call "ecosystem services" and being able to participate in this, there are benefits to every citizen in the United States for us doing those things that help preserve habitat, enhance water quality and enhance the natural resources.

So, yes, I have taken advantage of the EQIP Programs, but I’ve also – in implementing those practices, I have also ponied up my own dollars.

Greg Dalton: Tim Koopmann is president of the California Cattlemen's Association.

Tim Koopmann, I'd like to also ask you about – you have about 3,000 members, is that right?

Greg Dalton: In California where ranchers are running cattle, what do they think about climate change? Is it happening? And what possibly – could cattle and ranchers be part of the solution?

Tim Koopmann: Of the 3,000 members, like any group, we've got a diversity of opinion. And I think if you take any group of people, you're going to have a diversity of opinion about a lot of things. And I've got some people that will tell you that climate change is not happening, and then I've got another group on the other end of the spectrum that are saying, "Yes, climate change is occurring. Global warming is occurring" or whatever, and "Let's look for an answer to the problem. Let's see if we can be of benefit to try to help that." But, as with any group, there are folks that think both directions.

Greg Dalton: What do you personally think about climate change and how serious is it?

Tim Koopmann: I believe that climate change is occurring. I believe that it's probably occurring for millions and millions of years over time. I don't think that our attack on the environment with – or carbon production, has done a lot to help it. So I do think that we can do some things that would help to remedy this situation. We may not be able to stop climate change; it's naturally occurring, but we can probably slow it down, improve it or make it livable.

Greg Dalton: And how could cattle be part of that?

Tim Koopmann: I think that carbon sequestration is being talked about a lot. I think they're selling carbon credits on the CME, Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and all the boys in suits and ties that are making money off doing nothing. [Laughter]

Anyway, I think that our natural rangelands in the state of California and throughout the United States do a good part to preserve natural resources that sequester carbon. And I think that, with us as the Cattlemen's Association here, about 12 years ago, we started what's called the "California Rangeland Trust" and our goal in the California Rangeland Trust is to put perpetual conservation easements on rangelands.

The more rangelands, the more open space we've got, the more carbon we can sequester. Since the inception of the California Rangeland Trust, we have proudly been able to preserve and put perpetual conservation easements on about 238,000 acres of California ranchlands, and they are never to be developed and they can continually serve as a carbon sink if you will. In our small way, we're working at it.

Greg Dalton: Dave Robinson, is that good enough or do you still think that meat is evil and we’ve got to do away with all meat?

David Robinson Simon: Well, boy, you're putting words in my mouth. I can't disagree with that, I'll tell you. I don't argue in the book that we need to do away with all meat. I do argue in my book that we consume way, way too much meat, particularly in this country, but the rest of the world is trying to catch up with us and when they do, we're going to really be in trouble.

Climate change is only one issue. We haven't even talked about health problems today. In 1950, only one in eight Americans was obese. But we've almost doubled our meat consumption since then and, today, one in three Americans is obese. Meat is not the only reason people become overweight or obese, but the clinical literature shows there is a very, very close link to consumption of meat and dairy and overweight, obesity, cancer, heart disease and other diseases.

In this country, we consume more meat per capita than any other people on the planet. When the rest of the world catches up to us, and I said they're trying, the world will be short two-thirds again as much land as we'll need in order to raise the animals and the feed crops to feed them to make that very high level of demand.

Tim Koopmann: I think meat, like anything else, is a – it can be a healthy part of anyone's diet. Meat in moderation – it's just like is alcohol good for people. Is tobacco – well, tobacco is another deal. Probably not. But, I think, that meat in moderation can be part of anybody's healthy diet. Beef does provide a lot of amino acids and really does fit well into a healthy heart diet. There are 26 specific beef cuts that are right on par with chicken and fish as far as being low fat as well. But I'm a beef eater and I'll be the first to admit it, but I think the obesity issue in the United States is probably – I'd like to attribute quite a bit of it to the sedentary lifestyle that a majority of Americans live right now. I mean, I see people jog and I see people run and I see people cycling and hiking, but that's not the majority of Americans. Most people, they get home from work and they take an elevator to their apartment then they sit in front of the TV, unfortunately. Years ago, when my grandfather and my dad were working in the ranch, they ate big meals, but they worked hard, they were active, and both of them were in top shape into their 90s. I just think that sedentary lifestyle has something to do with it. I'm not promoting beef at every meal either, but I think it can be a healthy part of anybody's diet. It's a healthy protein source.

Greg Dalton: Beef demand is declining quite sharply in the United States in the last 10 years. And is that because of chicken, because of the health concerns that Dave Robinson is talking about? I mean, I think there is some pretty – the medical literature is pretty clear on animal protein and beef can be – have some real serious health concerns. Is that finally coming around? And, perhaps, the industry is looking to exports to make up that slack.

Tim Koopmann: Beef consumption has declined in the United States pretty sharply, as David mentioned.

We're at about 61 pounds, I think – in 2012, 61 pounds of beef per year per person per capita consumption. I think a lot of that probably has to do with price. We've gone through a fairly severe economic downturn in the United States and beef has always been kind of a premium product reserved for special occasions and chicken has been produced in abundant quantity and fairly cheap. So chicken has replaced beef as the primary protein on the plate, so to speak, over this generation. As far as the health of the product itself, again, I think it fits into a healthy diet.

Greg Dalton: Dave Robinson, I read something in your book which surprised me that chicken and salmon actually have the same amount of cholesterol as beef. That was news to me.

David Robinson Simon: They do. And that's one reason why some of the clinical literature that suggests that meat is good for us is a little bit misleading because, while chicken and fish have the same – maybe have much lower fat content than ground beef, they do have the same level of cholesterol. So, often, when clinical studies compare low fat diets and high fat diets, they say, "Ah, this looks about the same," but what those studies don't account for is, these very high levels of cholesterol – and we know that blood cholesterol is one of the risk factors for heart disease and other diseases.

Greg Dalton: How did you become – you're a vegan now, how did you become a vegan?

David Robinson Simon: I spent a day watching videos about factory farming and animal testing.

Greg Dalton: And was it a difficult transition, did you go cold turkey, just boom, never again?

Cold turkey – sorry about that. [Laughter]

David Robinson Simon: This happened when I was 44 and I was a junk food junkie. I spent – I ate my meals at Carl's Jr., Western Bacon Cheeseburgers, Big Macs, et cetera. That's what I ate for the first 44 years of my life. It turned out that my – for most of my adult life, my cholesterol was at about 200. My body mass index was at about 25, which is the threshold for overweight. I had acid reflux. I had a variety of problems. But, as I said, one day, I was all alone at my house, nothing to do, I watched hours and hours of these videos, and at the end of that period, it was like a hit on epiphany. A switch clicked in my head. So when you asked, "Was it difficult," there was no alternative for me. Suddenly, I simply had no way to eat animal foods anymore and this is – what's – so, no, it wasn't a difficult transition.

Greg Dalton: We're talking about meat and the health of our bodies and our climate at Climate One. Our guests are

Tim Koopmann, president of the California Cattlemen's Association, and Dave Simon, author of

Meatonomics. I'm Greg Dalton.

Let's go to audience questions. Welcome to Climate One

Joanne Davis: Hi, I'm Joanne Davis. I'm just wondering about the benefit on parts per million. I think if we're approaching the limit that's not reversible for climate change, and over what period of time and how much consumption would be – could we really make a big change if people were to reduce consumption?

Greg Dalton: I know that people such as Dr. Pachauri who's head of the interpanel – Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, has said that, reducing meat consumption is one of the biggest things people can do. Some people think that what you eat is more important than what you drive. People tend to think a lot about their cars, et cetera. The thing with a car is you make that purchase every 5, 10 years, whereas you make foods decisions, hopefully, if you’re lucky every day. So it takes a more sustained commitment rather than you can buy your electric car and think you're good for a while.

In terms of specific members, I don't have any in terms of the path, but I think we're growing – there's a growing recognition that food is a really big part of this and there's been a lot of focus on smoke stacks, power plants, automobiles. I don't know if Dave Simon you have anything to add.

David Robinson Simon: Well, I suggest in my book something that people will think of as fairly radical, but I suggest that we tax animal food products in this country. And the tax that I propose, in conjunction with some other institutional changes like restructuring how food stamps or the SNAP Program is used for people to buy food, would result in roughly a 44% drop in consumption of animal foods, and that, in turn, would have the effect of eliminating about three trillion pounds per year of carbon equivalent emissions, which would just be like garaging all motor vehicles and all motor vessels in this country each year this tax is in effect.

So, I think, reducing animal food consumption and production would have a major, major effect in mitigating or reversing climate change.

Greg Dalton: You also acknowledged in the book that that's politically unlikely, but you're putting it out there as a bold idea that you think will maybe get some traction because we don't like taxes on anything these days. We can't tax carbon pollution. We can't tax bad things. How are we going to tax something that a lot of people view as good? Americans like their hamburgers.

David Robinson Simon: Yes. No, that's – I don't disagree with that. But when Gandhi set out to dismantle British rule in India, he said, "If you don't ask, you don't get." So, I figured I would ask and we'll see what happens.

Greg Dalton: You just called him The Raj? [Laughter]

Let's have our next audience question.

Mary Siegfried: Yes, my name is Mary Siegfried. And I'm here today because I'm very interested in the issue. I am a former heavy meat eater turned plant-based. But I'm here because of my concern about the environment and you referenced the World Bank's reworking of the, I believe it was kind of a reconsideration of Livestock's Long Shadow, the U.N. study. And the two people who were involved in that for most experts, said that there was actually like an impact of 51% on climate from –

Greg Dalton: Carbon pollution coming from animals, right?

Mary Siegfried: Yes. I understood that there is both methane and ammonia emitted. Is that true, by animal farming?

Greg Dalton: So that's – we have – we've –

Mary Siegfried: And that the – I believe it's the methane, it has a very short half-life, something like 9 to 13 years. Which opens the possibility of cleaning that up or removing it from the – much more quickly than carbon dioxide, which has a longer half-life.

Greg Dalton: We talked about methane. Dave Simon, we did not talk about ammonia. Is that an issue from the manure?

David Robinson Simon: Yes. Manure emits typically four chemicals of concern: carbon dioxide, ammonia, methane and hydrogen sulfide, and these are all things that we should worry about. I'm not a chemist. I don't know about the half-life. That's an interesting issue. But, I think, we should be concerned about all of these.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next audience question. Welcome at Climate One.

Liz Fisher: I'm Liz Fisher from Citizens Climate Lobby. And my question was, how do we sort of compromise between Dave and Tim? What can we do to get more farmers to be like Tim? But Dave sort of answered half of my question with the carbon tax. We lobby for a carbon tax, a revenue neutral carbon tax. So, today, the question is what would you think about making that revenue neutral in terms of putting that money back in consumers' pockets? And then to Tim, how can we get more farmers to be like you and not the factory farms?

Greg Dalton: Let's start with that one.

Tim Koopmann, revenue neutral carbon tax is something a lot of Republicans support, including former Secretary of State George Shultz, many members of Republican administration. Is that something that could get some traction among the cattlemen and ranchers?

Tim Koopmann: First of all, there’d need to be a pretty good explanation because the idea of a tax, right off the butt, makes people bristle up.

But if there was an explanation that went along with that, the possibility exists that it would be accepted.

In answer to the question about more producers accepting some ideas and accepting the fact that it's a good thing to have endangered species on your property, it's a good thing to protect the resources and protect water flow, et cetera. I think we're making a lot of headway. I think we've got a lot of producers and growers in the United States. I know, particularly, in California, that think kind of the way I do. The problem with farmers and ranchers is we don't spend a lot of time with our PR people. We don't have agents and we've never talked about it too much, but a lot of us grew up taking care of resources and doing the right thing, we just never said much about it. I think we're out there and I think we're kind of picking those up that aren’t and dragging them along by the bootheels.

Greg Dalton: You might also say you worked for the city of San Francisco protecting a watershed and you found some common ground amongst some unlikely sources of that story.

Tim Koopmann: Yes, if I take just a minute to explain. About 2005, Steve Thompson who was the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Operations Manager for Nevada in California, was approached by conservation organizations when he started to work in Sacramento. He was accused by the conservation organizations of not spending the federal dollars wisely for habitat conservation and resource protection. Steve, at that point in time, asked these mainstream conservation organizations to identify the most valuable habitat in the state of California, and collectively, to come back to him mapping that area that he wanted – they wanted him to spend the federal money on. They came back with a ring around the Central Valley of California which identified the annual grasslands and the foothills of California as being the most biodiverse valuable habitat in the state.

Steve's response to them was that, unless we have a change in mind here, we're going to have a hard time spending on money there because 97% of that is privately owned by ranchers. So that'll give you some idea of what we've done as far as stewarding the land. What evolved from that conversation was, Steve said, "Unless you can work with the ranching community, we're not going to be able to spend the money there" and that started a little deal that happened in my shop, as a matter of fact, on a Saturday morning. It was in August 2005 of our first meeting with the California Rangeland Conservation Coalition. Anybody remembers being at the eighth grade dance where all the girls stood on one side and all the boys stood on the other? For the first half hour or 45 minutes, the only movement that went on was to go to the coffee pot and back to your side. But, after the end of that day, it was amazing, the much – as much discussion went on with good projects, good things we could do and since that time we've only grown. We have over 100 signatories to this coalition right now, and they include almost every conservation organization in the state of California, public agencies and ag organizations. And it was said that we can agree on about 90% of the issues and we could go forward and do good things. We will never agree on the 10% so let's not talk about it much, let’s just go and do good stuff. So that was a real – talk about having an epiphany. We can work together with the conservation organizations.

Greg Dalton: Tim Koopmann is president of the California Cattlemen's Association. We're talking about meat and climate and health at Climate One. Let's have our next audience question.

Pat Tibbs: Yes, I'm Patt Tibbs and I'm 75 years old. And, for most of those 75 years, I ate red meat. About 10 years ago, I stopped. Today, I want to thank you, Mr. Koopmann, for being as responsible as you are in producing beef. However, I will not be one of your customers.

David, a year ago, I stopped eating meat. I attribute that somewhat to the fact that my son and daughter-in-law are vegan. [Laughter]

I do listen to them and I determined just based on my health history, that eating meat wasn't healthy for me. And in the last year, it's been borne out in my blood panels and I thank you for writing your book.

Greg Dalton: Thank you for that comment. David, do you believe that there ought to be a choice that different people might have different choices and that's okay? We have meat eaters and vegans and there's a place for choice and that meat may not be bad for everyone or certain people have different bodies, different types?

David Robinson Simon: Absolutely. People need to make their own choices, but, I think the animal food industry in this country has successfully diminished the ability of consumers to make choices because it misleads us and it provides us with misinformation. There are many examples of this. I've talked about – I just talked about those studies that compare low fat and high fat diets and showed that there's no difference. But –

Greg Dalton: Another example is milk for children.

David Robinson Simon: $50 million per year is spent promoting milk consumption in our schools. The federal government stands behind so-called check off programs that message us aggressively with messages like, "Beef - It’s what's for dinner. Milk, it does the body good. Pork, the other white meat."

Now, I know Tim will tell you this is private industry, but, in fact, in 2005, the United States Supreme Court said that when you hear those messages, as a matter of law, that is the United States Federal Government telling you to eat more meat, notwithstanding that we already, in this country, we already eat in every age and sex demographic, more meat than the USDA says we should, and USDA continues to push this messaging on us. And I find that troubling because, as I mentioned, it diminishes consumers' ability to make informed choices. People walk to the grocery store at 4 o'clock in the afternoon and, because they have been bombarded with “beef it's what's for dinner” over and over and over again, guess what? They buy beef. People respond to advertising. That's how we are.

Greg Dalton: Tim Koopmann, is the government in the business of promoting meat and dairy?

Tim Koopmann: I'm a little familiar with the check off program that we have in the beef business and I would not say that it's – I would not agree with David that it's a government-sponsored beef promotion. It had to be legislatively approved because it requires the voting of the entire industry, if you will, whether we're going to have the check off or not. What happens every time a beef animal changes ownership, we make a contribution to the beef council if you will, and then research, marketing, all those things that go on with the check off program. But I'd certainly – I think it's divorced from the government. I think it's our own industry promoting our product.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question at Climate One.

Andrew DeCoriolis: Hi, my name is Andrew DeCoriolis. Tim and Dave, thank you so much for joining us today.

Dave, we talked a lot about climate today, of course, but when you were asked what made you change your own personal habits, you said it was watching videos and sort of experiencing what it is for the billions of animals that we raise on farms on this country.

What do you think the conversation is like, I guess, for all three of you, that we need to be having, that's actually going to move the needle to sort of change this entrenched factory farm industry? Is it about climate and carbon or is it about the experience of all the animals that live in these places?

Greg Dalton: Tim Koopmann, we've talked a lot about the small guys, but the fact is, there is what, two or three meat processors in the whole country. There's a concentration of power in the industry. How could that power be moved towards some of the things you're talking about?

Tim Koopmann: Wait a minute. He asked him the question. Hey! [Laughter]

Greg Dalton: All right, Dave?

David Robinson Simon: Oh, okay. Well, I think all of those, we're used to thinking about – well, people who think about these things, not everybody but I'm used to thinking about animal agriculture as having three problems: ethical, nutritional and environmental. With my book, I've added a fourth problem category which is economics, but I think we need to be concerned with all of these issues. We haven't even discussed the ethical issues today, seriously. I mentioned this fact that farm animals have no anti-cruelty protection. I'd like to quote just briefly, a Connecticut statute on this issue. In Connecticut, the law says, it is legal "to intentionally maim, mutilate, torture, wound or kill an animal, provided the act is done while following generally accepted agricultural practices." That’s a direct quote from the Connecticut statute. Every single state in this country has a similar law in place, either by statute or by judicial decision making. It's not always worded exactly the same, but the effect is identical. Farm animals can be treated virtually any way that is expedient and it saves money for the producers.

These animals lead terrible, terrible miserable lives. If you have not seen these videos, I encourage you to go look at the three-minute video of factory farming. In the one hour that we've been sitting here, a million animals have been killed for food in this country. One million animals in one hour and those animals all, except for the 200 on Tim's farm, led miserable, miserable lives.

So I'm focused on the ethics, but the climate issues are important, the nutritional issue is important and the cost – financial costs are huge.

Tim Koopmann: I'd like to respond just a little bit, and it's not just the 200 animals on my ranch. The vast majority of animals that I am familiar with and I have visited feedlots, I have visited many, many ranches over my years, farms, et cetera, and from a beef-cattle standpoint, I've also visited processing plants, slaughterhouses, if you will, and I have never been subjected to, what I consider to be animal cruelty. I am very adamantly opposed to the mistreatment of animals. I take it personally as an affront that anyone is making money by treating animals badly.

Greg Dalton: We do see downer cows being taken in, that sort of thing. You understand where this is coming from.

Tim Koopmann: The California Cattlemen's Association over 15 years ago helped to sponsor legislation, saying that downer cows were not to be transported to processing plants and we have worked diligently to get that accepted to federal level and that's yet to be. But in the state of California, we have pushed for that. I just – I don’t think there’s anything worse than mistreating an animal. I just don’t think it’s something that we practice and most of my constituents and most of my colleagues do not practice that.

Greg Dalton: Dave Simon, last word.

David Robinson Simon: I’d like to ask you a question, Tim. Do you – with respect to the animals you raise, do you castrate – for example, your male animals?

David Robinson Simon: Do you anesthetize them, when you do that?

Tim Koopmann: We use a paste gel that comes from Australia and we use an anesthetic and an antiseptic.

David Robinson Simon: Okay. I’m glad to hear that. I think that puts you in vast minority of beef cattle –

Tim Koopmann: There is a – and this is a practice that’s becoming more and more prevalent. We recognize that surgical procedure for castration which most people have their dogs altered as well, but it has been done sans anesthetic before for years and years and years of generations, but there’s a product in the market that more and more people are using it comes in a gel form and is a numbing agent.

Greg Dalton: And on that happy note, we’re going to end it there. [Laughter] Our thanks to

Tim Koopmann, president of the California Cattlemen’s Association and Dave Simon author of

Meatonomics. I’m Greg Dalton. Thank you for coming and listening to Climate One today.

[Applause]

[END]