Murder, Pollution as Policy, and Two Women Who Won’t Give Up

Guests

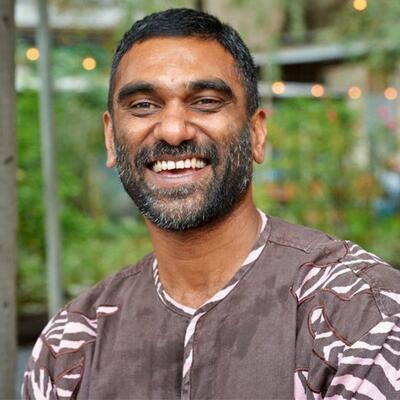

Alexis Madrigal

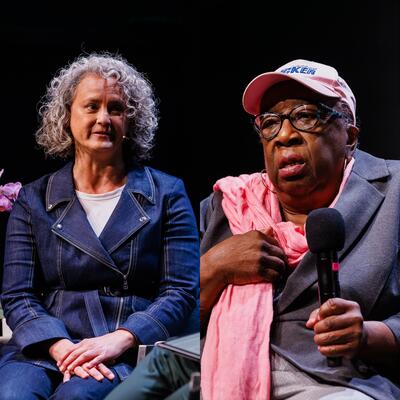

Margaret Gordon

Abby Reyes

Summary

Some may know Alexis Madrigal as the host of Forum on KQED, San Francisco’s NPR station. He’s also the author of “The Pacific Circuit,” where he chronicles the rise of Oakland’s ports as a key to shaping modern global trade, and the effects that had on the communities in West Oakland.

“This would accomplish multiple goals to put a port here: economic development on one side, and the further deterioration of this neighborhood environmentally on the other,” says Alexis Madrigal, “ you can see it through city documents all the way.”

Madrigal describes the West Oakland neighborhood as, “ disempowered, largely black, and [one] that the city had been trying to destroy for quite some time.”

Margaret Gordon is a life-long community organizer and co-founder of the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project. She’s known by just about everyone in the community as “Miss Margaret”.

“There's trucks running twenty four-seven in our neighborhood of West Oakland, and then when you went downtown or you went to Emeryville, there was no such thing happening,” she says.

Deeply aware of this injustice, Gordon had to take matters into her own hands when no one in power was addressing the air pollution problem in her neighborhood. “Nobody was measuring the cumulative impacts of having the trucks, the trains, the ships, and the cargo handler equipment that runs on diesel.”

“West Oakland Environmental Indicators at that time had to develop our own collaboration of agencies and bring our own data and research to them,” says Gordon. And in order to get that data, Gordon says, “I went to everything. I didn't miss a conference, a symposium. A seminar, nothing.”

In 1999, the Indigenous U’wa people in Colombia were fighting oil extraction near their territory, a project that threatened their land, their health, and their lives. Activist Abby Reyes had been witnessing a nearly identical struggle by indigenous people halfway around the world — in the Philippines — against the very same oil companies.

“I went to Project Underground, and my colleague, Denny Kennedy introduced me to Terrence Unity Freitas, who was also a young person — just like me — who was working with the Colombian U’wa people,” says Reyes. And it was not long until they were more than just colleagues. “That first day of learning about the U’wa’s struggle from him in the middle of our briefing, he stopped and asked me out on a date.”

In January 1999, Terence Freitas and two colleagues were planning to travel to a rural community in Colombia to learn from, work with, and support the U’wa who were standing in the way of one of the most powerful oil companies in the world. By the end of February, Abby Reyes received a call that Freitas and his two colleagues had been kidnapped by FARC, a Marxist-Leninist group that had been fighting the Colombian government for decades. Eight days later, all three of their bodies were found, murdered. Reyes says, “It was probably the worst moment of my life.”

It turns out Occidental Petroleum had been paying FARC for security. “Occidental made that clear to the U.S. Congress shortly thereafter, while they used the murders as a rallying cry for more war in Colombia,” says Reyes.

“The period immediately following the murders was a steep learning curve for me in, both figuring out how to navigate the waters of a tremendous grief and anger, and how to navigate Congress,” says Reyes. Her work continues today, “There's the blocking the bad, there's the building the new.”

Episode Highlights

1:31 - Alexis Madrigal on the effect of containerization on Oakland

6:37 - Alexis Madrigal on pollution as policy

12:05 - Margaret Gordon on the impacts of pollution in West Oakland

18:28 - Margaret Gordon on collecting data when no one else would

23:41 - Margaret Gordon on global climate change

29:14 - Abby Reyes on how she met Terence Freitas

37:30 - Abby Reyes on the taking risks

39:11 - Abby Reyes on the phone call that changed her life

50:08 - Abby Reyes on what she wants to focus

Resources From This Episode (3)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Kousha Navidar: I’m Kousha Navidar.

Ariana Brocious: I’m Ariana Brocious.

Kousha Navidar: And this is Climate One.

[music change]

Kousha Navidar: A few weeks ago we hosted some amazing conversations on the Climate One stage during San Francisco Climate Week.

Ariana Brocious: Today we’re bringing you some of those conversations – particularly the stories of two women who have faced very different challenges, but each has stood up to powerful forces in pursuit of environmental justice.

Kousha Navidar: Later in this episode we’ll hear from Abby Reyes, a community organizer whose boyfriend was murdered while fighting fossil fuel expansion in South America. It’s a deeply powerful story of loss and resilience that really moved me.

Ariana Brocious: But before we get to that story, we’re heading to West Oakland for an oddly similar story, where people in power weaponized pollution to push aside marginalized communities and expand the port. Then in the second segment, we’ll hear from one woman who stood up to those people in power.

[music change]

Kousha Navidar: Some may know Alexis Madrigal as the host of Forum on KQED, San Francisco’s NPR station. He’s also the author of The Pacific Circuit. In the book, he examines how the city of Oakland and its ports played a role shaping the modern economy.

Ariana Brocious: Madrigal joined Greg Dalton on the Climate One stage to share his insights into the forces that influenced global trade, exacerbated pollution, and impacted the people of West Oakland.

Alexis Madrigal: There's kind of two global forces that I really look at in the book. One is of course what happens after containerization, the development of all of this trade, which then puts more trucks, you know, onto the ground, but also puts more goods into Target and all these other things that people make use of.

Greg Dalton: And that innovation really started here.

Alexis Madrigal: It really started in Oakland, uh, through the Vietnam War. Really, uh, solved a major military logistical problem and that set up Oakland as the first like major container port on this side of the Pacific. And on the other side you've got Cam Ranh Bay in Vietnam because it really was for the military. Um, but that led through a variety of different companies and circumstances to, to Oakland being the first of the major container ports in the Pacific.

Greg Dalton: Wow. And San Francisco often overshadows it sort of, you know, brother on the other side So, is this part of a larger thing where the kind of Oakland innovates and doesn't get credit for it

Alexis Madrigal: Well, you know, I think that Oakland is sort of part of this metropolitan area, right? And that metropolitan area kind of has these like three components. One is sort of going across the Pacific, the kind of banking links, the, the political links, all these things. The other is like Silicon Valley, which is sort of down, uh, you know, south of San Francisco of course and contribute a lot of the information technology that's necessary to control these systems of production that stretch across the Pacific. But Oakland is sort of the part of this region that has both, it's kind of like the back lot, right? It's where you can sort of see the infrastructure at work. It's where you really get the worst impacts for people's health. Um, and it's also a place that sort of is inside the sort of understanding of technology in the Bay Area, but isn't kind of inside its logic, right? It's not, if you're in Oakland, you don't have to buy into what Silicon Valley is doing, but you can see it 'cause you're sort of proximate to it.

Greg Dalton: Hmm. Yeah. It's part of a, part of a bigger system. I get that. You also write that quote, the miniaturization of the transistor, the maximization of the cargo ship and the securitization of the mortgage are more related than they appear. And when I read that, I was like, Hmm. So connect, unpack that and connect those for us.

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah. Um, you basically need a lot of computer chips, that is to say, you know, transistors to do the sort of information technology, uh, and communication that controls these systems. It's really something longshoreman. Who are experiencing containerization as a form of automation, they're kind of the first people to point this out that these things are connected, right? That you, if you're gonna have these factories spread across the world, you need all this technology to, to control them. And then the US, which really developed this system of trade across the Pacific, encouraged all these export oriented economies along the Pacific Rim. Those economies have to hold dollar denominated assets, which then juice, uh, our, uh, our debt markets and all, all of the sort of money that we're able to use, here in the United States. And so that's really the relationship is it ends up becoming this kind of, uh, set of arrows. You can almost imagine these technologies, these dollars, uh, and these containers kind of all, all working together.

Greg Dalton: Transistors, of course, kind of, if not invented, you know, uh, popularized developed in Silicon Valley.

Alexis Madrigal: silicon in Silicon Valley, basically. Yeah.

Greg Dalton: so as trade got containerized, ships got bigger, ports got bigger, cranes got bigger. How did that affect port cities like Oakland?

Alexis Madrigal: Well, you know, back then Oakland was kind of a minor port city, right?

Greg Dalton: San Francisco had a port

Alexis Madrigal: San Francisco was the, you know, if we can imagine San Francisco in your head or anyone who's listening, you can look it up on Google Maps, you can see this kind of crown of piers that surround the city. That's where trade used to happen was like right in downtown San Francisco, right outside this building. The shape up for longshoremen before. Uh, before they got their union, were like, right, literally right on Barker Hill here. Um, kind of like the scene outside Home Depot these days, but like many, many, many more people. Um, and containerization basically required a lot more land. Here, ships would pull up to the pier, they'd unload onto the dock. A teamster would come and bring that stuff to a warehouse somewhere. A lot of it was in Soma, south of Market Street here in San Francisco. With containerization, you need a place to stick all the containers before all these diesel trucks arrive to take those things to distribution centers. The Targets and Walmarts of the, of the world. And so because of that, you found these, uh, companies like Sea Land, like Matson, these early container companies, knew immediately that they were gonna go to Oakland, where they had two important things. They had land, uh, that was right near the water, and they also had a neighborhood in West Oakland that was disempowered, largely black, and that the city had been trying to destroy for quite some time. Uh, sometimes I call the plot against West Oakland, and you can see it through city documents all the way. And the city of Oakland immediately sees like, oh, this would accomplish multiple goals to put a port here, economic development on one side, uh, and uh, and the further deterioration of this neighborhood environmentally on the other, in hopes of pushing people out.

Greg Dalton: Wow. Yeah, it's intentional. It's not like an accident that these things happen to be the way they are.

Alexis Madrigal: It is absolutely intentional. I mean, you've got a report in 1936, uh, major report about sort of the nature of Oakland buildings, uh, and, and city planning in which they literally say, we want to crowd out people who are living here. And the other part of it was, we are gonna segregate this neighborhood with a freeway. Um, to segregate out this sort of mixed race neighborhood that was the western part of West Oakland from the less mixed race neighborhood that was on the eastern part. And of course, West Oakland does end up surrounded by freeways, which of course has all the health impacts we're gonna hear about later from Miss Margaret.

Greg Dalton: So it's really pollution as policy.

Alexis Madrigal: It really is. I mean, it would, and it's, it's, to me, those, some of those documents are so amazing from that time period because you see them just saying it, you know, just like we're trying to do this. We know this is gonna make housing worse. We know this is gonna make people's lives worse, but this is the plan.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, the region captures the value of all this trade, you know, Silicon Valley's getting rich and sounds like Oakland is a sacrifice zone, what we call a sacrifice zone.

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah, parts of right. I mean, there are shipping companies and there are longshoremen who make money as a result of this trade. Right? There are, there's a table for them to sit at. There's a place where, um, both like the shippers and the people who do the work of, of shipping can, can get in on this sort of global, uh, fund. There really isn't a place for the community. I mean, the community essentially is just being, uh, dumped upon without necessarily being able to access the economic opportunities that the port, uh, had generated through time.

Greg Dalton: The Bay Area has such a reputation for environmental action that it's, you know, easy to not notice some of the perverse effects, which you, you, um, explore In your book, for example, you make the point that protecting undeveloped land in the seventies meant overburdening already developed land. So they're kind of protect. Marin or, you know, pretty places and, but you double down on pollution in places like Oakland.

Alexis Madrigal: also, you know, just the focus of the environmental movement right? Is, is on saving the Bay, which I think we're, we're glad that that happened, that it didn't all become paved in, doesn't look like the LA River. So I'm glad that that sort of stuff happened. I mean, the, all the open land that's been preserved, you know, outside of the, the like downtown and urban cores is obviously a good thing. At the same time, I mean. It's the reason why environmental justice was such an important corrective to what had happened in the environmental movement. You know, people. I think for too long and, and even today, uh, remarkably, despite all the amazing work of environmental justice activists, people still interpret, I think, environmentalism as being about nature and the out there ness, uh, and not, you know, people's lives and the health of, uh, of people's environments.

Greg Dalton: right. The, the, the, the Sierra Club, the verdant places.

Alexis Madrigal: Well, the Sierra Club is a great example because they actually have helped in this fight against, uh, uh, this bulk export terminal, which would send coal trains through West Oakland. Uh, Sierra Club has been a major component of that, of that fight as they sort of figure some the, the relationship out between these global issues like climate change, of course, most prominently and the local activism that's like so necessary because at the end of the day, like every fossil fuel plant, every mine, all these things, there's an, there's a local environmental situation. That goes right alongside and that directly impacts people even more than this real global picture.

Greg Dalton: Right? Right. And uh, so that's still happening today that, you know, 'cause coal is kind of declining in the US that they wanna get coal to export markets that might go through, uh, the port and West Oakland. So today we have this global trade Hub in West Oakland, you know, runs on fossil fuels. In a moment we'll bring on Ms. Margaret Gordon of West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project. Formerly, formerly. Um, and you almost titled your book, everybody knows Miss Margaret. So tell me what drew you to her?

Alexis Madrigal: I mean, you're gonna hear from her. Miss Margaret is a, a, a powerful leader. Someone who has brought people together, not by sort of diluting herself. By people being magnetized to her. People, you know, talked with her family, talked to people who've known her, uh, all through her life know, uh, talked with tons of people in West Oakland about her. And I think, you know, the, the main thing that I always think about Ms. Margaret is she like shows up. She's like showing up to stuff. She knows stuff and she shares that knowledge with a whole tree of people through, through West Oakland. And I think that sometimes we kind of forget. You know, one of my friends a social worker and he's like, sometimes a prescription is relationship, you know? And I think in a lot of cases when we talk about organizing people, we talk about what we are trying to do here on this earth. Sometimes I think people get a little too caught up with like, well, what are the ideas? What's like the solution? What's this like special innovation that's gonna unlock everything? And it's like sometimes the prescription is actually just relationship building. I mean, over and over. I feel like this comes up in Miss Margaret's work that like the reason they could get things done is because they knew the people, uh, through time.

Ariana Brocious: That was Alexis Madrigal, Co-Host of Forum on KQED.

Coming up, Madrigal talks with co-founder of the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project, who used the same system that threatened her community to protect it.

Margaret Gordon: There's still a bunch of us who have hope and faith in the law for the people who are most vulnerable to be able to get on the right path to saving our lives through justice.

Ariana Brocious: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Kousha Navidar: Help others find our show by leaving us a review or rating. Thanks for your support!

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious.

We just heard from Alexis Madrigal, who explained how increased globalized trade and container shipping created a slew of environmental injustice issues for the people of West Oakland.

The person at the heart of his story is Margaret Gordon, a life-long community organizer and co-founder of the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project. She’s known by just about everyone as “Miss Margaret”. She spoke with Alexis Madrigal on the Climate One stage about the legacy of fossil fuel pollution in her community - and what she has done to push back.

Alexis Madrigal: Miss Margaret, let's maybe start with the most direct thing, which is just kind of like the impact fossil fuels in West Oakland on your family, on the community, and sort of how you came to really see those impacts.

Margaret Gordon: Well, first of all, I'm a third generational West Oakland person. Um, my great aunts were riveters in Richmond during the war, and they raised my mother whose mother had died and they moved after the war machine was over in Richmond, they moved to West Oakland, and I used to come, I'm from San Francisco, but born in Richmond and every summer I would go to West Oakland, Eighth and Campbell for my summer, summer home,

Alexis Madrigal: a couple blocks from where you live now. You're right.

Margaret Gordon: You're right. I would go, uh, and play at Prescott School. Mm-hmm. All right. So that's how I know about West Oakland.

Alexis Madrigal: And what about when you were kind of coming into your, like prime as a community leader, like late eighties, early nineties, you moved back to West Oakland. Like what are the things that you were sort of seeing like, right in front of your eyes or feeling in your lungs, you know, that made you think like I should get involved?

Margaret Gordon: Why is this truck on my block? Why is this truck on this street? Why is this truck running this engine? Why it runs into the neighborhood store at at seventh and uh, seventh and Willow. Why? And why was the post office distribution center from where I live at allowing trucks to run their engines. Why was there was, there's trucks running 24 7 in our neighborhood of West Oakland, and then when you went downtown or you went to Emeryville, uh, there was no such thing happening. And then also Why is this black stuff on my walls when I open up my window? That's how coming out the tailpipe of the trucks. So there was a always been the, uh, the question why and who and who was going to give us the answers? Who's gonna give me the answers? And then, uh, I got a part-time job doing some community, uh violence prevention program. And I would go visit the school nurse at Prescott Elementary School, and I used to see all these inhalers and shoe boxes with kids' names on it or baskets, and I used to ask her why. She said, well, all these kids have asthma. Well I have asthma also? I said, well, uh, why is that so many kids? Why so many, so many kids? She said, well, I don't know. So eventually there was a project. Came to West. It was a small grant and what gave us a project, how to ask the questions to researchers about these issues as called indicators. And so one of the indicators was about air quality and that it rolled from there.

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah. You know, the air quality impacts in West Oakland were really always been about the trucks. Right. The trucks that are, and so did the trucks basically lead you right into the port? Is that a, like when you started saying, well, why are the trucks here? The answer is really the port and the, and the post office.

Margaret Gordon: it is also nobody would, was measuring the cumulative impacts of having the trucks, the trains, the ships, and the cargo handler equipment that runs on diesel.

Alexis Madrigal: So you get involved with all these issues. People get to know you in the community, uh, kind of legendary politician named Ron Dellums, uh, through a kind of difficult fight, gets you onto the Port Commission, the first ever resident of West Oakland to ever actually be on the Port Commission, which is the, I mean, literally this neighborhood is separated by like four blocks from like all this, all this port industry and you go at all these things through this maritime, uh, air quality improvement plan, right?

Margaret Gordon: Yes.

Alexis Madrigal: Um, how much of an impact were you able to make during that time, like in terms of cutting the amount of particulate emissions that are, uh, that are in the neighborhood?

Margaret Gordon: Well, it was a bottom up fight. and one of my saving graces what I had to make relationships with Agencies. Agencies and

Alexis Madrigal: like EPA, bay Area Air Quality Management,

Margaret Gordon: We as West Oakland Environmental Indicators at that time had to develop our own collaboration of agencies and bring our own data and research to them and let them prove it what we said or what we asked, or what was we had reported or recorded was accurate. So one of the things that we had organized as. I'm coming from a background organizer. We, we brought the agencies to one table so we didn't have to run over here. We didn't have to run over there. They came to our table in West Oakland. And then also eventually we did include the port staff and the city staff as needed. As needed.

Alexis Madrigal: And one of the things that I've always found fascinating about the work that you're doing during that time is, you know, when we talk about air quality, you know, oftentimes there's just like the one sensor, it's like a regional picture of it, and what your group did was go gather like street level data because that's where all the people are. That's where the lungs are, right? It is like down on the street. Right?

Margaret Gordon: Because we wanted to know from a truck go by that what's coming out, that tailpipe hit the sidewalks when you open your front door or open your window. What was, what was that? How much was that? And also what was the public health problems to us based on the data that we got from public health? The state, state public health department, the county, one out of five children from the age of zero five, end up in emergency services for respiratory disease. We know that, like I just said, uh, the individual schools in Westland, the kids had a, a school nurse had inhalers, uh, in the nurse's office. We also know that through a study that we did with Kaiser Foundation, that was a high level of cardiovascular disease with people between the ages of 55 and 68. So all these things eventually may, but keep publishing and making others, and also doing our own air monitor. We had these portable, uh, backpacks of air monitors that, that detected pm 2.5 and 10 that we were able to really get the, get the real certification and also peer review that we were right about there was stuff on the ground. It was not totally up in the air.

Alexis Madrigal: And there, you know, they also worked with, um, public health officials were able to show. There were, you know, the life expectancy for people living zip codes were just much, much lower than people living in the hills, which of course, people kind of knew, but you know, like Miss Margaret's saying, getting the data actually mattered. And it was important to, to make that data, uh, do stuff,

Margaret Gordon: Well. Also, people kept coming to us as we, the information got out, what we were doing, we had Intel knocking on our door because they wanted to put something in a cell phone, which I had no idea, was called an app that you could hold your cell phone up and you could calculate what's in the air your, your air quality in your vicinity. All right, so that, so we also had University of Washington come to us, put out, um, pre sensors throughout the neighborhood. We also did a project with, um, Google, the Google Earth car with Acoma of driving through the neighborhood and also, and also after that, who, how do we, um, energize the community with the information. So those are some of the things that had to be done often, often, often, to be more consistent and building collaboration and coordination of the work that we've done. Without that, we would never had been the, the West Oakland environmental indicators would not be in the position that it has been. Plus, like you said, I went to everything. I didn't miss a conference, a symposium. A seminar, nothing. Workshop. I didn't miss anything because it was necessary for you for the gathering of the information. You don't have the information. They would tell you anything.

Alexis Madrigal: And they're like, during this time too, I mean there's like five redevelopment projects of different kinds going on at different times. I wanna move us, um, to the old Oakland Army base. Uh, we've kind of referenced it earlier, um, that there's been this massive redevelopment of the army base. And as a piece of it, a developer has been trying to put in a bulk export terminal with money from Utah Coal Miners. And you have been one of the people along with no coal in Oakland that's been kinda leading the

Margaret Gordon: 15, years.

Alexis Madrigal: it's been 15 What do you think the fight against this terminal says about the struggle against fossil fuel

Margaret Gordon: Okay, let then let's go back to the redevelop. When the, the land, former military base army base was determined to be a redevelopment area and they had got federal funds to do the, some of the infrastructure work to change and the deal of writing the planning process. It was never stated that the developer would bring in a commodity called coal. It was never there. He inserted that as he could not find money to build out his terminal. So in order for him to be able to recoup money and uh, to build this and have investors, that's how coal got put there, but that was never intended as a commodity to be moved in Oakland.

Alexis Madrigal: How do you think about the connection between these like hyper-local environmental issues that you end up working on on the ground with like the really big picture, you know, global climate change?

Margaret Gordon: I see the global climate change as about global climate justice, the justice piece, we have no real plan how to insert justice to those who are most vulnerable and impactful. Every projects that I know of internationally has started from the most indigenous people asking the questions why this is happening to us. I just came back from, um, in early April, a community of international and national EJ groups far as Polynesia organizing themselves to ask the question: Why is this sea level rise as, uh, as, and what is the mitigations that we should have to protect ourselves? And that's one of the problems. We have too many others wanna come in and talk about what they want to do instead of working with and not with. And, and sometimes for those most impacted, don't come in with your plan, your agenda. Exactly. Like we don't know. We have the lived experience at our realities. That's the problem that too many big NGOs and others come in, don't think about the justice piece. That's the last thing on. 'cause they, they see their theory. is the only thing that matters and not what the people who are are most impactful or vulnerable have the experience and have experience and the reality. That's a whole different mindset in the planning and a strategy.

Alexis Madrigal: You know, in this political moment you've got the Trump administration going after environmental justice groups, cutting all kinds of, uh, grant funding going after, uh, really going after history. And I know, uh, there are some people out there feeling, you know, hopeless, feeling disempowered. And when I run into you, uh, in Oakland over the last few months, that is not the feeling I have gotten from you. So, as someone who's, you know, spent her career, you know, battling powerful interests, oftentimes from outside of, you know, or quite far away from the levers of power. Like what, what would your message be to people?

Margaret Gordon: Well, I come from a family of people who have always been engaged. And I have lived through the anti-poverty movement. I lived through Nixon. I lived through Reagan. Now I'm living through Trump. All right, so what's the, the only difference is that from those other situations, he has the power of the pen to make these executive orders, but there's still a bunch of us who have hope and faith in the law for the people who are most vulnerable to be able to get, get on the right path to saving our lives through justice. And I think that's one of the people you got to have the faith and understanding of how I, I'm also, I'm a history friend. I love history and I always wanna know how people overcame adversity. And I think one of the things that public education and families do not know that type of a history. Some of us have had struggles. You struggle for unity and struggle more for and, and has to be not at the top, but at the bottom where the people are most vulnerable So that's my, that is my word that, that you can't, you just can't fall. If you fall down, you gotta learn how to roll over and get back up.

Alexis Madrigal: Also the backbone too, though, right? I mean that's one of the things I like when we've talked a little bit about this particular political moment, you've kind of been like, I feel like these people don’t how to fight.

Margaret Gordon: Well, that's true. All right, but so, but fighting and being violent is two different things. Fighting and violence is two different things, and people connect those and they don't know how to separate. My fighting back is always about, hey, the pushback when the stuff is incorrect, pushing back when. Those things that you seeing in your mind's eye, you think that you improving my life? No. I wanna be able to express and have a voice and my own design plan of action strategy, land use. design on all those different things. People need to understand about West Oakland. It was an unincorporated community for until the sixties. We still have communities unincorporated throughout the United States where they're always dumping something Because what if it's unincorporated? The land is cheap, cheap, and you get to do what you wanna do based on who is the developer and who is the planner. And none of that stuff is based in public health to take care of who are there living in those communities.

Alexis Madrigal: Miss Margaret, thanks so much for all your work. Thank you. Thanks for joining us.

Kousha Navidar: Coming up, how do you stand up for what you believe in,

while facing deadly violence?

Abby Reyes: Yes, there's the power of the gun. Yes, there's the power of the dollar. But there is also a power that lives in our lived and inviolate connection with the earth

Kousha Navidar: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

This is Climate One. I’m Kousha Navidar.

In 1999, the Indigenous U’wa people in Colombia were fighting oil extraction near their territory, a project that threatened their land, their health, and their lives.

Our next guest, Abby Reyes, had been witnessing a nearly identical struggle by indigenous people halfway around the world - in the Philippines - against the very same oil companies. In her book, “Truth Demands: A Memoir of Murder, Oil Wars and the Rise of Climate Justice,” Reyes tells the story of how she met Terence Freitas, one of the U’wa’s allies in Colombia. She talks about how she and Terence fell in love and the price he paid for his activism.

She shared her story of grief, resilience, and courage with me on the Climate One stage, beginning with how she and Terence met.

Abby Reyes: I went to Project Underground, and my colleague, Denny Kennedy introduced me to Terence Unity Fretis, who was, uh, also a young person, um, just like me, who was working with the Colombian U’wa people, native to the northeast corner of Columbia, and they were fighting the very same oil companies.

Kousha Navidar: There's that parallel that you were seeing.

Abby Reyes: The parallel was indeed in the, in that it was the same corporations. The parallel was also that the community was very clear. The U’wa people in, in that part of Columbia have been, um, the voice in, in my youth, they were the ones first introducing me to the idea, we've just got to keep it in the ground.

Kousha Navidar: And I we're gonna come to that. Mm-hmm. But you mentioned somebody very important that I want to learn more about, uh,

Abby Reyes: Mm-hmm.

Kousha Navidar: Who is Terance, what did he mean to you? Tell us a little bit about him.

Abby Reyes: Uh, Terance Unity Fretis, um, was a UC Santa Cruz graduate environmental studies, aikido expert, um, early, early, um, environmental and indigenous rights advocate. Early. By early, I mean young.

Kousha Navidar: Mm.

Abby Reyes: We were, we were just out of college.

Kousha Navidar: So like early, mid twenties.

Abby Reyes: Early mid twenties. Um, and he became the main liaison between the ua, Pueblo and, um, the eight to 10, non-governmental organizations who worked in the areas of environment, of human rights, of indigenous rights here in the States, Australia, Europe, um, who had come to walk alongside the U’wa community when they figured out that they needed international solidarity because their, uh, requests of those oil companies to meet face to face was being unmet. And Terrence, um, very quickly. In that first day of learning about the U’wa’s struggle from him in the middle of our briefing, he stopped and asked me out on a date. And,

Kousha Navidar: uh, what did he wanna do?

Abby Reyes: Well, our my, well John Seed, who's an Australian deep ecologist was in town and he was performing that night. And I had not seen John since I was in high school. John and Joanna Macy, who's a teacher of mine, had profoundly influenced my, own understanding of my relationship to the Earth and through their practices had really taught me that it was actually within my right and within my duty to go ahead and let myself feel the grief about what we were doing to the planet. And that was, you know, when I was 15, 16, that's, that was part of, um, building that context for me, um, off of a, of a childhood that entailed a, a lot of, um, reverence for the interconnectedness of life.

Kousha Navidar: So, Terence asks you out, uh, you're both doing important work together, getting to know each other. Uh, you, you did mention the importance of the U’wa in the way that they thought about the earth, A part of the book that was meaningful for me to read. You said, uh, U’wa leaders were the first people I ever heard call for a humanity to simply keep the oil in the ground. “For them. It isn't about a sustainable development framework or natural resource management. It is about reestablishing the equilibrium between the world above and the world below the surface of the earth.” That was from your book. How did that affect your thinking?

Abby Reyes: Well, what I learned from my U’wa colleagues. Was the steadfastness and the comfort and agility in going ahead and saying that out loud and acting from that, uh, understanding of one's interdependence with the rest of life.

Kousha Navidar: Saying what out loud.

Abby Reyes: Saying out loud that we are the earth protecting itself. And going ahead and acknowledging that those that are bringing us the kinds of environmental injustice and harms that we may talk more about today are, we are part of the human family. And when that harm is present, the, the understanding is at once a fierce defense, a fierce. message of no. And of wow, we've got a long way to go.

Kousha Navidar: You used the word understanding, which leads me to another part that struck me. Uh, it's kind of like a, a catchphrase that the U’wa used. I suppose they, they described outsiders as quote the people who don't think well. And I thought about that cultural divide between those within the community and those without, how can cultural divides. Be bridged when the powerful entities see indigenous folks as backward or slow and locals see outsiders as fast and careless.

Abby Reyes: There is a skill of knowledge brokering that the communities with which I have been lucky enough to work over years are training their young people to do, and the key to it is troubling this notion of power, of who has the power, what kind of power, what kind of power is it? Yes, there's the power of the gun. Yes, there's the power of the dollar. Yes, there's the power of the signing of the cross. But there is also a power that lives in our lived and inviolate connection, uh, with the, with the earth and with the rivers running and with the cycles of the movement of air and water that, uh, is a. A different starting point and one that connects us when we're willing to speak from it and willing to harness it connects us powerfully to the generations that have come before us, that have gotten us to this moment of collective acceleration that we are experiencing right now. And, allows us to stand in allegiance with generations yet to come. When we figure out, uh, how to go ahead and let those relationships be true, we have a better chance of getting in alignment with, um, with the people who are ready making the pivots we need to make to the far horizon, uh, and doing some of that work together, which is joyful work even in the face of devastation to imagine what is it, what is it when there are no asthma, um, respirators in the nurses office at the, at the public school, what is it? When we have drinkable rivers,

Kousha Navidar: Yeah.

Abby Reyes: what is it? When we have the rains return, the gentle rains return to this region, that is the far horizon. Some of that is more intermediate. but the kinds of power that become available in the knowledge brokering, Have some of that at the source. So, so that the conversation

Kousha Navidar: and Terrence was a part of that knowledge brokering and trying to, to. bridge the U’wa with that knowledge of also what was happening outside of the community as well. Right. And how

Abby Reyes: Yes, it was, it multi-directional.

Kousha Navidar: And, and so let's talk about that power a little bit. We're going to January, 1999. Terence, two of his colleagues, Lahe and Ingrid, are preparing to enter a country in war. This is from the book, a conflict in which hundreds of thousands of people had been killed. They were planning to travel to a rural community to learn from, work with, and support the U’wa who are standing in the way of one of the most powerful corporations in the world. And I read that and I wonder what kind of person is that? What kind of person knowingly, willingly takes on that risk?

Abby Reyes: Earth Rights Defenders around the world, in legion, take this risk every day. Terrence, Ingrid, and Lahe, were taking this risk at a particular heightened moment of Colombia's internal conflict In a region in which oil pipelines were a magnet for armed violence, they took the risks that they took in the context of knowing that they, uh, were not alone and in relationship, in deep relationship with, uh, indigenous folks who were living those risks every day themselves. Yeah. And so part of what I learned recently looking at some of Terrance's notebooks from the time was his own musings to himself of “if Roberto's gonna, you know, risk his life, why shouldn't I?” He wrote that.

Kousha Navidar: Let's jump ahead a little bit to, uh, February 25th, 1999. Tough day, uh, on the way to the regional airport to come back home. They were kidnapped. Ingrid Lahe, Terrance. You heard that the three of them had been taken by people who self-identified to the U’wa as the FARC and, and the FARC is the Marxist Leninist group that fought the Colombian government for decades. Um, then about a week later you got a phone call. Can you just tell us about that phone call?

Abby Reyes: Well, the first phone call was on that day of February 25th when we found out they had been kidnapped. And the, that phone call led us into a sprint that was unending and terrifying for the next eight days while we were trying to find them and get them safely home. And the um. The movements of that week entailed the bringing together of course of three families and chosen families of the people who had been taken, but also multiple Native American North American tribes. The U’wa Pueblo itself in Colombia layers upon layers of, um. Non-governmental organizations from various sectors here in the States and all around the world. Um, it was the, it was a massive undertaking under what for me, as a 24-year-old was extreme duress.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah.

Abby Reyes: And then the phone call you are referring to on day eight. Um. Was the moment in which our colleague, um, Jose Barerra, who was um, Ingrid's dear friend, we were all assembled at the American Indian Community House in Manhattan. During the kidnapping mobilizing for the release, he received a phone call from Ingrid's office that three bodies had been found. And at first it didn't sound like their bodies, it sounded like different bodies. So for about half an hour, I was like, this is not them. These are other bodies. Bless, bless the passing of those people, but those are not our people. In that, in that moment, Ingrid's 12-year-old son came in the room and asked me what was happening, and it was probably the worst moment of my life. And then we confirmed. One woman with an eagle tattoo, one woman with a triangle and one, one young man with dark, curly It was them.

Kousha Navidar: Worst day of your life,

Abby Reyes: Bar none.

Kousha Navidar: And to be clear, um, you think Occidental Petroleum had been paying FARC protection money?

Abby Reyes: Occidental made that clear to the US Congress shortly thereafter, while they used the murders as a rallying cry for more war in Colombia as a rallying cry for increased military aid, military aid connected to Colombia's commitment to opening up more oil.

Kousha Navidar: And do you feel like that was typical of how multinational corporations were operating in these countries at the time? Can you talk more about that?

Abby Reyes: We can rely on the words of the oil company themselves. About how typical this was.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah.

Abby Reyes: It was a practice common, um, in that particular conflict and is well documented in political science literature around the world. Because oil pipelines are easy targets, often oil companies need to pay to prevent them from being bombed. Yeah. so that those are the payments that are, that the oil company, in this case, Occidental itself, has testified to Congress about,

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, you were 24. Right. This, and I'm sure many other things, but this sent you on a path of your career and a very long path with the U’wa people, either in direct contact or, or, or tangentially just for, for, for justice, for truth. And it was a long road, right? I appreciate so much, Abby, your willingness to sit here and, and relive these moments with us. And, and there are chapters to this and the chapters that follow are, are long and hard. And I'm wondering what happened with the oil development and with the U’wa people in the intervening years?

Abby Reyes: Well, the period immediately following the murders, uh, was a steep learning curve for me in, um, both figuring out how to navigate the waters of a tremendous grief and anger and how to navigate Congress. And, I learned, I, there were many way more seasoned advocates, together with us, from whom I learned a lot and even while the, um. lobbying this pitched battle between the oil companies and the, the people's movements, um, from rural Colombia who had marshaled and come to Washington to tell Washington, no, we don't want this, um, escalation of our war. It's gonna play out in the countryside in a manner that that will eviscerate our economies, our local economies, and changed the face, um, of this countryside. Uh, that was all playing out here in the States, while at the very same time, the um, oil company used the escalation of war as a cover for quickly moving its equipment into place. And so in response, this highly organized and cohesive set of indigenous communities blocked the road, blocked the road for months in what became a regional rallying cry there for, for saying no. Thousands of people, not just indigenous people. Also the farmers. Also the students, also the clergy, the media, the human rights bar, um, camping on the road and at and, um, and occupying the, the two farms where Oxy wanted to sink a new exploratory well, which the community has long asserted, the permission to think that well was ill given by the, by the Colombian government. Uh, in the course of saying no with their bodies, they were met with more violence. Violence that indeed, um, hit a crescendo. Ultimately, in the forced violent removal of people from blocking the road, including women and children, including moms who were carrying babies on their backs and were pushed to the edge of the river and had to choose the river. More life taken. Babies can't get out of a mom's carrier that quick. So. All of the, these were, these were happening at the same time. So, so to answer your question, it yes. And because of the steadfastness we were also pursuing every legal venue possible. Like Miss Margaret was saying earlier, we were in the room, we were in every room because we were, we were many of, many different capabilities, uh, from different positionalities, uh, with different kinds of access to different rooms. And so one of those was our, the longstanding petition in front of the Inner American Commission on Human Rights against the Colombian government on behalf of the U’wa community to say, look, the government has not done the required consultation and consent process here, uh, rights that are enshrined for Indigenous peoples, um, long before the 1999 murders. But then you, we, we would do well to evoke and recall that one of the people whose life was taken with Terence was Ingrid Washinawatok, a beloved menominee leader from Wisconsin, one of the main architects of the, um, UN declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples that got passed seven years after her murder. Long story short, just a few months ago, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights decided Casa U’wa decided the U’wa case completely in favor of the community. They, they won a recognition of the wrongs by the Colombian government against indigenous peoples in a decision that strengthens the right of indigenous peoples across Latin America.

Kousha Navidar: I can't imagine how it must have felt for you to be taken on like the, the worst moments of your life to feeling justice in, in some sense, be served, some release of this work that you've been working on. In December, 2023, the Colombian government became the largest oil and coal producer to endorse the Fossil Fuel Non-proliferation Treaty. So to kind of give some context to this, there are signatories of the treaty. They pledge to leave undeveloped resources in the ground, which is kind of what the, what people were saying all along Columbia says, yeah, that sounds good.

Abby Reyes: Actually, they were right. Yeah.

Kousha Navidar: You've been on such a journey with this and it has taken you far beyond just Colombia as well. Now you're the Director of Community Resilience Projects at UC Irvine. You have such a wealth of knowledge to draw upon.

Abby Reyes: Mm-hmm.

Kousha Navidar: Um, our fossil fuel economy has been supported by the idea of sacrifice zones. I heard it in the conversation just before ours. How does your work today challenge the idea of sacrifice zones?

Abby Reyes: Oh, sure. The work today here in California is joyful, joyful work I work with community leaders in climate-vulnerable places here in the state and their academic allies to learn how to work together better so that they can accelerate community owned, community driven, just transition solutions.

Kousha Navidar: And I wanted to touch on that because something I've learned about your work is that your current teaching and advocacy focus, not just on, on fighting the bad quote unquote, but building the new. And I guess the last thought to leave ourselves on is, um, what new do you feel like we most need to build?

Abby Reyes: What I'm learning a lot from my, um, my comrades in Santa Ana, California, which is a Mexican majority, um, midsize city, south of LA in the northern part of Orange County. It's the community to which I'm accountable in a daily kind of way. Um, they are innovating uh, the infrastructure for incubating worker owned cooperatives for putting into actual brick and mortar actual acres of land, community, land trusts urban farms. The infrastructure for mutual aid that, you know, we, we saw rise during the pandemic and that is still every day relevant and useful, um, and necessary infrastructure as we, as we confront climate disaster as well as health equity, infrastructure, and when I was telling our, our U’wa companions about this California based work, one colleague from the community reflected, well, it's the same work. the same work. We're doing the same work. There's the blocking the bad, there's the building, the new, and it is actually part and parcel of the same work. And that's where my next, um, that's where my next writing wants to go.

Kousha Navidar: Well, I, I can't wait to read about it. And, um, for what you've written now, I just, on behalf of everyone here, I just wanna say thank you for putting it onto the page for, um, taking that lived experience and doing something with it, um, and for sitting with us now, it, it, it means a great deal to me and to everyone here. I'm sure

Abby Reyes: It means a great deal to me. Please know that.

Kousha Navidar: Abby Reyes is the Director of Community Resilience Projects at University of California, uh, California Irvine, and is the author of “Truth Demands. A memoir of murder, oil wars, and the rise of climate justice.” Abby, thank you.

Abby Reyes: Thank you.

Ariana Brocious: Hey, it's Ariana and Kousha, and at the end of our show we're doing this thing now called Climate One More Thing, where we share something that we've read or come across or heard of in the week that's climate related and often, but not always uplifting. Kousha, do you wanna go first?

Kousha Navidar: Oh, thank you. I'm so excited. I've been looking forward to giving you this one. So I have a movie recommendation. It's called the Assessment, and it. Is about a future in which this couple played by Elizabeth Olson and Hamesh Patel wanna have a kid. But they are in a like post climate crisis world where the government controls all of their resources. So the government sends a representative, played by Alicia, a candor. To any home of a couple that wants to have a kid and the, the character observes the couple for a week to determine if they are fit to have creepy. Yeah, it is creepy. So that is just the start. It gets creepier and more like, uh, engrossing the further into the week you go along with, uh, these three characters, and I thought it was really cool.It's sci-fi, it's thriller, it's climate fiction. So I thought you might like that Ariana.

Ariana Brocious: I do, I like Cli-fi and maybe in the hopes of staving off that dark future, I will share my story, which was something I saw in the news this week, which is a program called Charge Scape. This is a joint venture between BMW, Ford, Honda and Nissan, and basically it's working with the.Growing number of EV owners around the country to, um, connect with local utilities and let utilities draw on those EV batteries at times of high demand on the power grid. So this makes the grids more resilient. Um, it can, you know, avoid shortages and cutoffs and things like that, and these EV owners get paid. So, it's a really interesting program. It's just getting off the ground. Not very big yet, but it does. Build into this idea that as more and more people buy EVs, we're gonna have this grid of batteries across the country. And if we can connect that with the grid we already have, we will be that much more resilient.

Kousha Navidar: You had me at, I can get paid. I just need to buy. Yeah, that's a perk. I just need to buy an EV first.

Ariana Brocious: And that’s our show. Thanks for listening. Talking about climate can be hard, and exciting and interesting -- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. Or consider joining us on Patreon and supporting the show that way.

Kousha Navidar: Climate One is a production of the Commonwealth Club. Our team includes Greg Dalton, Brad Marshland, Jenny Park, Ariana Brocious, Austin Colón, Megan Biscieglia, Kevin Lemons and Ben Testani. Our theme music is by George Young. I’m Kousha Navidar.