On The Run: Voluntary and Forced Climate Migration

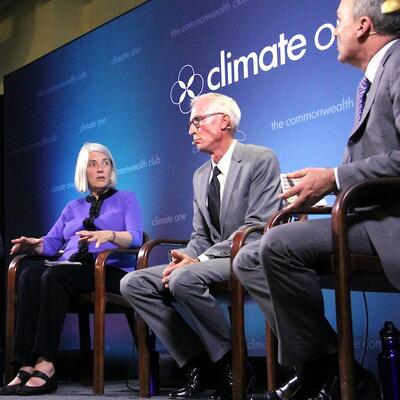

Guests

Colette Pichon Battle

Abrahm Lustgarten

Kayly Ober

Summary

The climate crisis may not be the sole driver of human displacement but it is a contributing and growing factor, exacerbating the misery of already struggling communities. Abrahm Lustgarten, senior report at ProPublica, explains what that displacement might look like as the climate crisis continues to intensify:

“When you look and model out climate change into the next couple decades by 2070, that 1% of the planet that has historically been inhospitable expands to 20% of the planet's surface... And when you look at how many people presently live in that 20% area, it's about a third of the planet's population, which is about 2.5 billion people now, but by 2070 will be 3 billion people.”

According to the UN Refugee Agency, climate change typically creates internal displacement within countries before it pushes people across national borders. And the World Bank Group’s Groundswell Report presents a worst-case climate scenario, in which as many as 216 million people could be displaced globally within their own countries. Kayly Ober, Senior Advocate and Program Manager of the Climate Displacement Program at Refugees International, explains how that report can impact policy:

“What the scenario does is show you that if we put into place policies now that people on the move, one, could decrease. But, two, you’ll be able to address that movement in more holistic or positive ways. And so, it’s really hugely dependent on if we as a society actually come together and decide to address these problems with proactive policy.”

In the United States, there is no system in place to effectively handle internal climate displacement. Colette Pichon Battle, Co-Executive Director at Taproot Earth, comments on how internally displaced persons were handled in the wake of Hurricane Katrina,

“We just don't have a deep knowledge about the rights of internally displaced persons in this country. This is an international law and international standard, but it applies globally. But because the US had never really seen this kind of disaster before, we never really thought about what it is to have people displaced within our own borders.”

Battle also explains how the US is unique when it comes to adopting international law that could help: “We have not made strides as a nation to affirm or to advance a lot of these international laws and treaties that are in place. In fact, we are often the lone non-signatory, or us and a few other countries not signing onto treaties and rights that we want to recognize.”

While much of this displacement is involuntary, many with means and foresight are able to move before things get really bad. Battle comments, “These are obviously people with wealth and privilege. And wealth and privilege isn’t just money and whiteness, it's often access to information... What we're seeing, especially in South Louisiana and throughout the Gulf South are upper-middle-class white families moving to a place where they can be safe. So, folks from South Louisiana moving to places like Tennessee or even Kentucky or these other spaces keeping their homes in Louisiana or trying to sell them while the markets are still showing that this is a decent investment. But also selling them knowing that whoever purchases them whoever purchases these homes they will be stuck with a 30-year mortgage that once it's over will have real estate completely devalued, certainly lower, if not at full zero.”

Related Links:

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

The climate crisis may not be the sole driver of human displacement but it is a contributing and growing factor, exacerbating the misery of already struggling communities. According to the UN Refugee Agency, climate change typically creates internal displacement within countries before it pushes people across national borders. While much of this displacement is involuntary, many with wealth and foresight are able to move before things get really bad. How well are governments prepared to handle an influx of people driven from their homes - and support those who are left behind?

Abrahm Lustgarten, senior reporter at ProPublica, has reported on climate migration and the models helping to predict what that human flow will look like in the future. Lustgarten wrote that by 2070 more than 3 billion people may find themselves living outside the optimum climate for human life. That number blows my mind. I asked him to explain.

Abrahm Lustgarten: Yeah, you know, it's an extraordinary number and it’s far greater than you know what many scientists talk about when they talk about migration. But it's based off of a study that was published in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, which looked back over 6000 years and found that humans lived in a relatively small niche in terms of the environmental conditions. The temperature and the amount of precipitation that exists in the places where they live. And that as those patterns have shifted human populations have shifted with those patterns. But the places that were inhospitable on the planet in the past are relatively small they cover about 1% of the planet surface. And when you look and model out climate change into the next couple decades by 2070 that 1% of the planet that has historically been inhospitable expands to 20% of the planet's surface, the planet’s area. And when you look at how many people presently live in that 20% area. It's about a third of the planet's population which is you know about 2.2, 2.5 billion people now, but by 2070 will be 3 billion people. And so, that doesn't mean of course that you know that 3 billion people will move in some mass wave of migration, but it means that 3 billion people will find themselves coping with the discomforts of how their environment has changed to various it'll be more extreme in some places and less extreme in others, but it will be a negative change for one in three people on the face of the planet. And some portion of those people will be making decisions about how they respond to it, either being displaced or choosing to move.

Greg Dalton: Often, we think about climate migration, we think about forced migration but that's not the entire picture. How does voluntary migration compare to forced migration?

Abrahm Lustgarten: Yeah. So, this is just a really clear distinction and you know in my work and in the academic work it’s described as sort of slow onset change versus fast disruptive change. And it’s kind of obvious to think about what happens when a major hurricane destroys a city like New Orleans and those people look for a place to go in response. But the other end of the spectrum is my experience with wildfire in Northern California. It's that almost imperceptible shift that sort of chips away over time and increases the burden of a decision that may or may not lead to my moving. And that kind of migration worldwide is directly related to the means that individuals have. So, there's a wealth component to basically, the greater the wealth of an individual, the more ability that they have to be mobile to move their family or to move to another country or to choose a different place to live. And so it means that we’ll see a shift first in populations in pressured areas of the people who have the greatest ability to seek a new economic opportunity or something like that elsewhere.

Greg Dalton: You have written about a great transformation underway in the eastern half of Russia and how Russia aims to win the climate crisis by refashioning itself as a powerhouse food producer. The title of your article in the New York Times Magazine was how Russia wins the climate crisis. So, how has the invasion of Ukraine impacted that calculus?

Abrahm Lustgarten: Well, it's proven the global dependency on Russian and Ukrainian exports of grain. Russia is already you know the world's largest producer and exporter of wheat is just an essential supplier of food to the rest of the world. And that gives it an extraordinary amount of geopolitical leverage over the countries that depend on those imports in North Africa and the Middle East and elsewhere. And, you know, Ukraine is an example of how this sort of willful disruption of that pipeline of food supplies can be destabilizing and can also bend you know other countries other sovereign nations to the will of a country like Russia. The climate component you know which doesn't directly relate to Ukraine but is an opportunity potentially for Russia is in the fact that, you know, northern parts of the world will see a softer landing or softer transition as the climate warms. Not a problem-free transition by any means but one of the opportunities that comes with Russia that you know the world's largest national landmass is the potential opening of more land to farming. And that's already happening in the Russian Far East, which is part of what I looked out at through my reporting. So, lands you know that were frozen not too long ago that were tundra and solid with permafrost are already thawed. And as they're thawing are being quickly developed by Russian farmers by Chinese industrial agriculture firms for the growth of crops for the growth of wheat for the production of animals for meat and so forth. And so, whether or not Russia fully capitalizes on that or not, you know, kind of remains to be seen. But there's an opportunity there for economic growth. Russia being an example of you know of any northern country. And there's research, including by a researcher named Marshall Burke at Stanford University that has also examined the impacts economically to countries as the climate warms. And most of his findings are that where you know in the middle and southern part of the globe or in the United States southward that climate change will have a negative economic effect, but the inverse of that is that north of the middle of the United States he projects a positive economic effect. So, the GDP per capita growth in Canada might increase by about 230%. And in Russia it might increase by about 400% and, you know, per capita is a key phrase there. So, these are countries with relatively small populations. I mean you think about the opportunity for migration or the inevitability of migration of populations. There's a potential connection between the influx of people, the influx of a labor force in those regions and their ability to seize on that.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, there’s fascinating research that productivity peaks at about 55° average temperature which no coincidence is the average temperature of Silicon Valley and some other very highly productive places. Some US mayors in cities are preparing for an influx of residents due to accelerating climate disruption. Tell us what's happening in places such as Buffalo, Ann Arbor and elsewhere.

Abrahm Lustgarten: Yeah, you know its early days in this conversation and for this process but you are starting to see certain regions, anticipating that they will be destinations for a shift in population as the climate warms. The mayor of Buffalo, New York, has talked several times about Buffalo being a climate destination city. It's not clear yet from a policy perspective of exactly what that means, or how that will manifest. But it's a really explicit acknowledgment that they expect people to move there. They expect the environment in Buffalo, which can be pretty harsh in the winters with its lake effect snow on Lake Ontario to be a more inviting place with bountiful freshwater in a climate change future. And that they plan to capitalize on those changes. The similar expressions of optimism and planning in the sustainability plans for the state of Vermont as you mentioned Duluth, Minnesota and really you know around the Great Lakes I'm hearing and seeing cities and regional planners start to think about what the population changes in response to climate might be, how they size infrastructure in the future taking that change into account. And, you know, and what a warmer future might mean for those particular places.

Greg Dalton: And how about Atlanta? How does Atlanta fit into the migration we expect within the United States?

Abrahm Lustgarten: Yes, so what we see globally with climate and migration is what's called stepwise migration. And it’s basically that people who are displaced or are pushed into moving as a result of environmental factors tend to want to move the shortest distance possible. They're not looking to be thousands of miles away from home and community and the lands that are familiar to them. And the southeastern United States will face multiple pressures, including sea level rise and extreme heat and increasing prevalence of hurricanes. And the southwestern United States has some of those risks, plus extraordinary drought. And as people move out of those areas, Atlanta is one of the nexuses their projected pathways. There's a researcher out of Florida State University named Matt Heuer a demographer who has studied the displacement from sea level rise on US coasts and used previous IRS and census data tracking how Americans have moved to project where the Americans who are displaced from the coastlines might go. And his figures are an estimation of about 14 million American migrants displaced by sea level rise alone and his numbers are the ones that lead to that projection for nearly half a million to a million people moving into the Atlanta area.

Greg Dalton: You said that by and large, governments are not well prepared it’s early days but hedge funds are. They’re looking at these numbers you're talking about. Can you give an example of that, how markets are starting to recognize this?

Abrahm Lustgarten: Yeah. So, you know, like any dramatic change the opportunity to speculate on that change is just an enormous opportunity to amass wealth. So, you're seeing hedge funds invest for example, in water rights in the Western United States, buying up water that they can either hold or resell or limit and profit from as its scarcity increases. You're seeing some of, you know, the same sort of speculative change in the real estate market, the largest real estate firms in the country are trying to carefully time their investments and their exits from communities based on you know when their models or the best advice that they can get will project a change in demand for those areas. And often that change in demand is negative, which is that you know an interesting explicit recognition of the migration phenomenon. But their timing when they expect that certain communities will collapse and when the demand for housing or for office space in those communities will collapse.

Greg Dalton: You mentioned today how economic development and growth helps countries and communities prepare and be resilient to climate disruption and how the volatility that climate brings could bring wealth creation, wealth transfer. Some people can choose to move. There are communities who don't have the resources to respond to the climate crisis or be able to move. Can you tell us about these trapped communities?

Abrahm Lustgarten: Yeah, mobility is commensurate with the ability to move. And one half of the equation, especially in the United States will be what happens to the communities that are left behind. So, these will be communities that either are have higher rates of poverty or older populations that are little more resistant to making major life changes or choose to remain in difficult places because their ties are so deep, or their spiritual connection to their land or their community history or family history. There’ll be a variety of reasons why people won't move. But what my reporting suggests is that in the places where the effects of climate change are dramatic, but communities are most resistant to change or where people are trapped in those communities there’ll be a negative spiral effect essentially. Some people will move, the tax base of certain communities will decline it will degrade further. The quality of the schools which will lead to more people moving. And what you'll arrive at the end of that sort of degrading process is that the only people left are the people who have no ability to leave at all. And that will present a different sort of burden and obligation for policymakers to address which is just as important as preparing for and building infrastructure to meet expanding populations and destination cities will be, you know, devising new ways to support the changing systems and communities for the people left behind either by propping up their school systems or ensuring that there's employment or offering other sorts of social support.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I’m thinking brings images of the people left behind in New Orleans when Hurricane Katrina came in because there were no buses and they didn’t own cars they couldn't get out. Abrahm Lustgarten, thanks for sharing your insights on climate migration fast and slow, forced and voluntary. Thank you.

Abrahm Lustgarten: Thanks for having me, Greg.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about voluntary and involuntary climate migration. The US has a mixed track record for handling the aftermath of natural disasters. The response has been especially lacking for poorer and communities of color. As the climate crisis brings more extreme weather, how will the US respond? And how can we break the cycle of inequity, where the poorest are hit first and worst?

Colette Pinchon Battle is President of Taproot Earth, an organization that describes itself as a non-profit, public interest law firm and justice center with a mission to advance structural shifts toward climate justice and ecological equity. I asked how her personal experience in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina affected her understanding of migration.

Colette Pichon Battle: In the beginning, right after Katrina what you knew what you heard and what you saw was a number of people from the Gulf South being moved out of a really bad situation. So, they had stayed for example, during the storm and the federal government and others were just getting people out of the zone, the disaster zone. This looked like a lot of one-way tickets on either airplanes or buses or trains. And I was in DC at the time and I was helping to shelter folks or orient folks who are landing in DC and found out that some of them didn't even understand where they were going. They knew they were getting out of New Orleans, they knew they were getting out of Louisiana but they didn't know exactly where they were going. Many of them had never left the Gulf ever. Prior to Katrina, Louisiana had the highest population of people who had never left the state. And so, we're dealing with people who had never left outside of Louisiana before they didn’t know the difference between Dallas and Dulles. And many of them thought they were going to Dallas and found themselves at Dulles Airport in Northern Virginia. And it was really scary to watch how inhumane, or in-personable that experience was for folks in the midst of trauma. I think I also when I went back home, I saw how many immigrants were being brought into the country through legal immigration processes, although they were being labeled as illegal and unlawful. The truth is that they were coming in on business and agricultural worker visas through these big companies that were often seen only in the aftermath of war. So, you think about like Halliburton there was a big group here, the Shaw group. These big companies, Fortune 500 companies, are used in disaster cleanup. They clear roads. They put the bridges back together, you know, they do all of that but they actually use a lot of immigrant labor and I had no idea about that. And to see the numbers of immigrants that were being brought in specifically from South America and Central America. But then also watching the numbers of particularly poor black folks that were being pushed out of the region. It made no sense, right. There was a whole new wave of people coming in while there was one wave of people being pushed out. As an African-American that was disconcerting to say the least to watch that process. And as an immigration attorney my job was to try to help the folks who needed support with their immigration status. Yeah, it was interesting to see how those systems were maneuvered, right. So, the seasonal worker visas was how they brought a lot of folks in but on those worker visas when you lose your job you lose your status. That's very different from the highly educated worker visas where if you lose your job you have months to find another job, right, and what that looks like. And so, watching folks ask for their paycheck be fired, and then lose their status and their paycheck was not a one off. It was a system. And I realized that this is a system that is employed over and over again, right. So, our immigration laws really benefit large corporations, but they don't benefit the worker. And so, just thinking about that, thinking about the opportunities of all of these black men who were out of work when there were thousands of jobs that were being given to immigrant workers at half the price, right, half the normal wage, I would say. So, watching like, you know, $14 an hour jobs go down to eight and $6 an hour and then not even be paid out.So, it's really changed my understanding of what it means to have a network in place, right, a family network in place what it means for our immigration laws, what it means for unemployment impacts, especially on black men. This all really came rushing in all at one time during this process.

Greg Dalton: And Katrina was a big national wake-up moment for many people, the first real extreme climate driven disaster. Have we made any progress or learned anything since Katrina in the system or the same system in place say for example when hurricane Ida hits Louisiana and goes all the way up to New Jersey?

Colette Pichon Battle: Yeah, when we talk about migration the same system is in place, which is insufficient. First of all, we just don't have a deep knowledge about the rights of internally displaced persons in this country. This is an international law and international standard, but it applies globally. But because the US had never really seen this kind of disaster before, we never really thought about what it is to have people displaced within our own borders. Those are internally displaced persons different from refugees, which is a word I like to correct people on and even reject when we’re talking about climate migration inside of the US border. So, an example is in South Louisiana, we've got folks moving getting out of harm's way in an acute disaster but also the slow-moving migration that we see happening due to sea level rise. All of this is happening within US borders and the rights of internally displaced people apply here. We have not made strides as a nation to affirm or to advance a lot of these international laws and treaties that are in place. In fact, we are often the lone non-signatory or us and a few other countries not signing onto to treaties and rights that we want to recognize.

Greg Dalton: We've been talking about people displaced and who involuntarily moved from their homes or forced from climate impacts fast or slow. Let’s talk about people who are moving voluntarily. There’s certainly a shift underway where people who are looking at the climate and moving before their town burns or the water runs dry. These are obviously people with wealth and privilege. What are your thoughts about that migration?

Colette Pichon Battle: Yeah, I mean I think that last sentence hit it all. These are obviously people with wealth and privilege, right. And wealth and privilege isn’t just money and whiteness, it's often access to information. It's often analysis. I was just talking to this climate leader older white man who just you know made a comment about him and his family moving to Canada. And I was like, hmm, smart move. Someone who's been tracking this for a long time. What we're seeing, especially in South Louisiana and throughout the Gulf South are upper-middle-class white families moving to a place where they can be safe. So, folks from South Louisiana moving to places like Tennessee or even Kentucky or these other spaces keeping their homes in Louisiana or trying to sell them while the markets are still showing that this is a decent investment. But also selling them knowing that whoever purchases them whoever purchases these homes they will be stuck with a 30-year mortgage that once it's over will have a real estate completely devalued, certainly lower if not at full zero. Where I live, which is a coastal parish where we’re not going to see any value be able to be given to these homes because the roads and the bridges and all these things aren’t gonna be upkept. We’re seeing those types of divestment from our state government right now and really forcing relocation of folks down in the lower parishes, but to get back to the folks who can move I think they're looking at the writing on the wall. I mean it's interesting being in this red zone, right, the south where and places like Florida and Texas and even Louisiana for a long time you couldn't say climate change. But mostly you couldn't say that because they didn't want markets and people to react to it. I think people are looking at the writing on the wall and deciding that their future is better off not in this hurricane alley. Not in this heat zone and able to make the choice, but have the wealth and access and information to do so.

Greg Dalton: Well, in 2020, 90,000 people moved to Arizona, which is already facing severe drought problems. Lake Mead is like scary dry like running out this summer. This is an example of a trend of people moving into climate risk areas where there's been fires and droughts, etc. What do you make that kind of behavior?

Colette Pichon Battle: I think it's really interesting because I think, you know, it's one thing to be a climate advocate for the last 17 years and to watch people come into a knowledge and a reality around climate change. I mean, how long did that take? It took such a long time for people to just really kind of get it. I think what we weren’t counting on is the political instability and the political fervor and marketing that is happening at the same time, right. So, I think when we look at places like Arizona even Texas is seeing some big moves into it. Florida is seeing moves into it. Like why would anybody be moving to Texas or Florida at this point, I'm not certain, except for the politics. Now there's some political reasons to start moving to those places. There's actually you know invitations for people to come in and build your business here and move your family here because of the politics and the laws and the you know benefits as it's being proposed to folks. And I think it's being done without any analysis around climate. I think it's an interesting mixture of people not being able to discern what's actually happening globally, not believing that the United States is going to have any impacts from this very sort of disjointed impact of climate that will happen to others and not us. And I think it's part of a political reality where people are being invited into spaces to build stronger political roots.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I think there’s also some cognitive bias. People think bad things happen to other people or in the time frame I'm going to be there; I'll get out before the really bad stuff happens and it will work for me for a little while. According to a NEWSY report, economists predict going forward that poor communities will end up getting paid to relocate because it's cheaper while rich communities will likely see a lot of money pouring in to make their buildings more resilient. Is that happening you've talked a little bit about what happens after disasters. But could this climate resilience, kind of exacerbate the disproportionate allocation of resources?

Colette Pichon Battle: It's a complicated question. Paid to relocate is I think the wrong way to understand what is likely to happen. I think buyouts is what folks are referring to. And buyouts really have to do with sort of percentage of the wealth of your asset, right. So, what happens when you don't have an asset? What happens when you don't own your home? Paid to move is not what I've seen. I’ve seen declarations from the state that say we will no longer be repairing this road. We will no longer be sending first responders out past this point. We will no longer be providing any kind of assistance in this way or that way. And so, folks are being told that you'll be on your own and you can make your decision from there. And then I think you know we’re also looking at federal dollars that can help to create new communities which is what we’re seeing with the first federal dollars that came for sea level rise migration or relocation, rather, in Louisiana. Nobody was paid to move but the communities that people were being asked to help co-develop and move to, those were paid by federal dollars. So, there wasn't an exchange of money, but there was this sort of shifting of location. I think in watching the wealthy communities and what's happening and what’s gonna likely happen. Yeah, I think you know now we get to be green, right. Now you get to do everything the right way. Let's help those with fortify what they have. And this is I think the way of the US the way of the Western world, right. There is a group of people who have something that needs to be secured. Let us secure it. The rest of the folks don't have anything that needs to be secured so we won't secure it. And then you watch the breakdown of that very flawed theory instead of thinking of things like you know these disasters are going to come why don't we, one, not build in places that are going to flood. Two, reinforce the places where the most vulnerable populations live first. And three, ask the folks who have wealth to take accountability and responsibility, not for any wrong action before a new global reality that includes the US and what we need to do. I think we have not figured out how to distribute dollars in a fair way in this country. I've watched it over and over and over again in every single disaster from Katrina to BP and all of the ones beyond. Because I think we don't have a prioritization of the right people, and we don't even talk about the vulnerable populations the right way. We say, you know these folks are vulnerable, they're most at risk, they're marginalized. But the truth is that we live in a country where the systems and everything that we've had in place for all of this time have created a vulnerability by targeting particular populations. And if that were an accepted truth, then our new stance and our new priority should be on repairing the harm that has led to the vulnerability and led to this climate vulnerability as a way of accountability, right. So, this isn’t us giving out anything to people who don't work. This is us acknowledging that we have targeted groups of people throughout this country for a very long time and created climate vulnerabilities that now need to be addressed as a priority. But I think this is a moment for us to take really big leaps. We could use this moment to repair past harms. What an opportunity. Now, what we lack and what we need to find is visionary leadership willing to show some courage around shifting our thoughts and our priorities.

Greg Dalton: We’re increasingly seeing the environment and climate used as excuses by some on the right to push anti-immigrant ideas and even carry out violent acts like mass shootings. How big a threat is ecofascism fueled in part by fears of caravans and mass migration into the United States?

Colette Pichon Battle: Ugh, what a question. I mean hate is a product of fear. And fear is what our entire cognizant country is going through for one reason or another. And I think the climate crisis I think it scares people. It scares me. It should scare all of us. This one’s a big one and this one is bigger than any sort of one systems failure, right. This is everything and this is all of us. And so, because I think we don't have good social practices around fear, because I think we've never really addressed racism in a way that gets to the heart of the thing and really takes us to a much more reparative place, I think we’re going to see it play out. I think we’re seeing it play out. I think this is what people meant in the aftermath of Katrina when we said the word disaster. It was not just a storm. It was the storm on top of history on top of broken systems on top of divestment from this region, on top of all of that that led to a disaster. And what we’re seeing now is the creation of a slow-moving disaster rooted in racism and white supremacy and oppression and really, I think labeled as protecting our country or keeping people out. I think what we’re not seeing in the analysis is how US national and global policies are accelerating migration from the very places that we’re seeing caravans. You know how are our free trade agreements actually creating situations and realities that people have to migrate away from, be it economically or now even based on climate. None of that is part of the analysis. It's just the brown people coming that we seem to fear and allow to occur. As I worked in immigration law for so many years, you know, I watched people talk about immigrants and never really meant Western European immigrants or even Eastern European immigrants. What they meant were brown people coming from the border or black people coming through our airports. And it was cold language to say you know those brown folks those others are coming to take what we have. You know if you're going to have that analysis there you have to at least ask why are they coming, what's driving them here. It's not I mean we can see from our murder rates and our police brutality rates and our you know all of these other struggles we’re having, people aren’t coming here because this is like a really great safe place for brown people to live, grow and thrive. That's not what's happening. They’re moving to save their own lives.

Greg Dalton: We’ve talked about fear driving migration from the Global South into the North. We’ve talked about fear of privilege white people in the United States. They're afraid of losing something. You acknowledged having fear about climate change. How do you hold that fear? Do you think about staying there in a place you know that’s gonna see climate impacts and suffering? Or do you also have those flight fantasies that I think everyone who has this conversation has at one time or another?

Colette Pichon Battle: Yeah, you know, fear is powerful. It is powerful and necessary, right. You don't just have this emotion for no reason. We have it because our survival and our lives depend on it. I think we’re in a moment where we have to discern when our fear is being catalyzed and manipulated versus when it's being catalyzed for our survival. And so, I have decided to stay in South Louisiana but I can make that choice because I'm single; I don't have children. I don't have all of these things that many people have to worry about and I know I can make a decision like that that many families can’t make. But I intend to stay on the land that my people are from. We've been on that land since before it was the United States. And if there's one Pichon left standing it'll be me, and I hope we can figure something out before then. But you know the odds are that my community is not gonna make it. And so, I have to absorb that fear and think about what it is to witness what is my responsibility in the face of great loss, not just loss of my physical property but loss of the history that goes along with that. I think it requires me to conjure a big courage and I try to conjure that courage in others. I do think though more than sea level rise which is what is going to destroy my community physically, I think the heat is another consideration. I stayed during hurricane Ida last year and you know we were without power for over a week and the storm was one thing but the heat was a whole other ballgame. And I'm getting older. You know what does it look like to leave the region during the hurricane seasons and then come back for the rest of the time. It used to be that that could happen, right. I could be gone for four months or so, but hurricane season is widening. These storm seasons are getting longer officially by two months now. So, I think fear is necessary. We can't lose it. We have to be able to discern when it's being manipulated. And in the midst of the worst kind of fear we have to find deep courage and I think that's the moment we’re in. I think about that with climate. I think about that with white supremacists. I think about that with even the state of our political, our political state of affairs right now requires all of us to recognize the fear in our bodies and recognize what we’re feeling is real and probably necessary. But also, to examine what it is to show great courage in moments of great fear.

Greg Dalton: Colette Pichon Battle, thank you for sharing your courage and your fear and your insights on migration in the age of climate. Thank you so much.

Colette Pichon Battle: Thank you, Greg.

Greg Dalton: The United Nations says the number of forcibly displaced people globally recently surpassed 100 million. That’s more than 1% of the world population. The top causes cited were the war in Ukraine, civil wars, violence, persecution, and human rights violations. Until recently, climate wasn’t tracked as a factor for global displacement.

I asked Kayly Ober, Senior Advocate and Program Manager for the Climate Displacement Program at Refugees International, what kind of data there is on global migration when it comes to climate.

Kayly Ober: We actually have a really interesting data set that's collected by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre every year where we can enumerate the number of people that have been displaced in the past year due to weather-related disasters, That number this past year was 30 million people displaced by weather-related events. And actually, that follows a trend from the year before which also found that 30 million people were displaced due to weather-related events. So, we can see sort of a consistent trendline there.

Greg Dalton: Okay. So, about 30 million people on the move inside their country borders because of climate related events. We hear about hotspots. What regions will be most affected by climate displacement?

Kayly Ober: I think we can say that every single region of the world will be affected by climate displacement in some way. I think those regions that are particularly prone to sort of natural hazards. So, they're prone to sort of hurricanes or cyclones for instance. Or let's say people that live there are more dependent on rainfall for their livelihoods like they are farmers, subsistence farmers. They will be much more impacted by sort of climate shocks than other regions. And so, we’re particularly interested in those regions that have those characteristics and also might have some underlying simmering tension or conflict. So, you'll find that for instance in the Sahel or the Horn of Africa, for instance. And you also find those natural hazard prone areas like in South Asia like Bangladesh, poster child for sort of flooding and cyclones for instance.

Greg Dalton: Right. And what are the differences between quick onset and slow onset climate impact? There are hurricanes and tornadoes that happen really quickly and dramatic and drive a lot of dramatic television footage. And then there’s the really slow unfolding droughts and melts that are really a whole different tempo. Which ones cause the people to flee their homes?

Kayly Ober: That’s a really interesting question. Mostly because we have really good data or like you said the media tends to cover sort of onset events really well, right? We can see the displacement happening real time. It's very tangible and easy to see. And so, when we look at sort of the for instance the numbers, we talked about 30 million people displaced internally due to weather-related events that’s largely sudden onset events. You’re evacuating in the face of a cyclone you're sheltering really quickly away from that storm. You seek higher ground because of that flood. And so, we can really track that displacement. When it comes to slow onset events that unfold over a long period of time, we’re talking desertification, we're talking sea level rise. Minute change may happen every year and maybe it's not as obvious to those experiencing it on the ground and it slowly creeps in and erodes livelihoods for instance. And so it may induce people to move but it's harder to really pinpoint when that tipping point is. And so, that’s why we don't have great data about it because it's very layered and complex because of the way it unfolds and also because it’s not just as dramatic looking like it is with sudden onset events.

Greg Dalton: When things happen quickly it's visible and it's clear why people move. Elsewhere in this episode we talk about voluntary movement and involuntary movement. Do poor people leave first or they’re the last to leave? Because it can take money to move, and yet often it might be desperate people who are forced to move.

Kayly Ober: Yeah, I think in particular with climate related events. There's a huge gray area between sort of voluntary and involuntary movement. There are many sorts of qualitative case studies that show that in the face of sort of these weather-related shocks these climate-related shocks, the poor tend to move first because they have to, right. So, the livelihoods that they usually depend upon such as farming, right, are often irrevocably damaged. And so, in order to sort of overcome that shock they’ll usually migrate somewhere where there is an employment opportunity that’s not necessary linked to weather. So, often it’s rural to urban migration like you go to cities to find sort of informal jobs there. We also find the poorest of the poor don't have the capital necessary to move. They don’t have the economic capital to mobilize, they don’t have the social capital friends or family in the cities that can welcome them or tell them where jobs are. And so, often they are what we call trapped in places that are impacted by these events.

Greg Dalton: And there’s talk about building resilience in cities in order to absorb climate migrants. Of course, over the course of human history there’s been rural to urban migration that is one of the through lines of human civilization. So, what can cities do what do cities need to do to be able to prepare to absorb climate refugees and climate migrants?

Kayly Ober: Well, first I think cities have to acknowledge that there will be more and more people moving to them, especially in the face of climate change. Just for the very reasons we outlined before, right. So, as it becomes harder and harder to earn a living in rural places, especially with things that are related to the weather like agriculture, the more people will move to cities and we see that trend probably intensifying in a number of different sort of projections out there, right? So, one, it's first acknowledging it. And two, it’s also preparing for it. So, I often really reference this one project that is quite interesting in Bangladesh. They're trying to identify secondary cities in which they are able to make them more climate resilient and migrant friendly. So, ensuring that the infrastructure in those cities are actually resistant to different sort of climactic changes. Ensuring that migrants are welcomed and integrated, that they have access to stable formal jobs that have good contracts, right, or well-paying. That they have access to social protection, right, so that they can send their kids to school, they can access healthcare. It's basically cities need to offer sort of a stabilizing force in the face of climate change and be prepared in that way.

Greg Dalton: In the past I’ve talked to people about climate migration. People will often say refugees don't identify themselves as climate migrants they may not even depending on their income level and education level may not even really understand climate change. They just know that their crops failed or something happen that compelled them to move. Until recently, there really was no legally recognized definition of climate refugee. In 2020, the UN High Commission on Refugees issued legal considerations to guide the interpretation and steer international discussions about climate refugees. What did you think when that happened and what is the significance of that UNHCR consideration?

Kayly Ober: Yeah, these UNHCR legal considerations were hugely important in a number of ways. First, it was the first time that UNHCR really went out of their way to include climate change in any sort of assessment. Really grapple with it in a full-throated way. And basically, what those legal considerations say is that yes, the 1951 Refugee Convention is quite narrow in nature to become or to be qualified as a refugee you must still qualify under that definition, right. So, you must be crossing a border. You must be persecuted based on a number of characteristics like race, religion, social group, etc. But what you must also do if you are assessing or adjudicating a refugee claim or asylum claim is also assess what will climate change might play in the context of that persecution, right. So, for instance if there has been some sort of climate related event like a cyclone and your house had been destroyed your crops had been destroyed, you know, you're stranded you are having issues recovering or being resilient. And your government because you happen to be of a particular social group purposely withholds aid from you, then you might have a claim to persecution, right. What the legal considerations paper also does is say like, look, there are other sorts of refugee definitions in different regions, like in Latin America there’s a court declaration. In Africa, there's the OAU convention which really has a more expansive interpretation of refugee, including cases of public disorder. So, the argument is climate change or climate related events would qualify in cases of public disorder, right. So, it’s just trying to slowly nudge that refugee definition to be more broad or more all-encompassing.

Greg Dalton: According to the World Bank's Groundswell Report the climate crisis could force 216 million people across six regions to move within their countries by 2050. How would the displacement of that many people affect the world as we understand it today? 216 million people on the move.

Kayly Ober: I think the thing that Groundswell Report does well is present a number of scenarios, right. So, the 216 million number is actually worst-case scenario. So, we’re on a high emissions trajectory. We have high income inequality on sustainable development. It's not very green, you know, it's not very resilient, it's not very equitable. And so, in that case in that worst-case scenario that many people will be likely to move inside their borders because you know climate changes had been ramped up and those impacts were being felt by that many people. And I should say like again that's only internal numbers. They don't even try to grapple with those crossing borders. And what the scenario though does that show you that if we put into place policies now that people on the move, one, could decrease. But, two, you’ll be able to address sort of that movement in more holistic or positive ways, right. And so, it’s really hugely dependent on if we as a society actually come together and decide to address these problems with proactive policy.

Greg Dalton: And some of those policies are encouraging people to stay in their regions where they are rather than go from Africa to Europe or travel great distances, which kind of makes sense if you want to keep communities intact. There are also could be sort of a connotation of, let's keep the people on the Global South where they are. Let’s admit it, rich white North kind of doesn't want to be overwhelmed by hordes of climate refugees. What are the power and geopolitical dynamics there?

Kayly Ober: Yeah, I think the US and EU, for example, don't have a great track record of welcoming migrants or refugees. I mean we've had our moments, certainly, but in most recent years we’re not doing a great job. And I think often we talk about sort of climate-related refugees or migration in a way that makes it seem like worst-case scenario that hundreds of thousands of people will be coming to our borders and it will just be a crisis, right. The caravan narrative that we heard time and time again with the Trump administration, right. I think all it really does is stoke sort of anti-immigrant sentiment seeds a rise in xenophobia and a hardening of borders rather than actually grapple with the issue which is we need to cut emissions and we need to be realistic that people may need to move because climate is changing. You reference that those in the Global North often point to the Global South and say, you know you can move freely just in the Global South not to our borders, right. And I think you know, pessimistically or cynically you might say that's because it’s the containment strategy, right. And we do have a history both in the US and in the EU of investing in development in order to contain, right. But it’s also sort of just logical because people do actually mostly move across neighboring borders, right, there is huge trade ties there, there are usually you know a lot of migration back and forth between those borders because of that trade. And it is the easiest way without sort of xenophobic tension underlying it to really allow people to move freely across borders in the face of a disaster which is what you want people do to move freely to seek safety.

Greg Dalton: Right. In our recent episode we spoke with Wanjira Mathai who heads up Africa for the World Resources Institute, and the sort of deglobalization era she’s supportive or speaks favorably of trying to increase regional trade ties in Africa to bolster regional economies and kind of keep dollars and people closer to home rather than stretched out through this long global supply chain. Clearly, leaving home is a painful and fraught decision for any family or individual. What has your observation of global migration taught you about how people navigate personal risk? Do I stay do I go, you know, fight or flight, stay and hunker down or go to someplace that might be better?

Kayly Ober: Yeah, I think the decision to migrate is usually complex and contextual. So, rarely if ever, is climate change the only factor or only driver behind the migration decision, right, usually exacerbates underlying tensions, right. So, whether it be a social or economic or political. Usually those things are more of a tipping point than climate change, right. However, I think that humans in general are not as rational as we like to think so even these models and projections, we’re talking about it’s based on a rational man, right. And even just this afternoon I was talking to somebody whose family actually had to flee Syria during the you know in the last during the Civil War. And she said that she asked her aunt, “When are you going to flee?” And she said, “Well, your cousin has a dentist appointment this week. So, I don’t think we can do it this week.” And she was flabbergasted by that. And the point of that story is it's highly complex and complicated humans are really bad at assessing long-term risk. So, in the face of like a Civil War you should be better at making that risk to move. However, with something like a slow onset event it's really hard to assess sort of long-term risk. The human brain is really, really bad at assessing long-term risk in fact.

Kayly Ober is Senior Advocate at Refugees International. Kayly, thanks for sharing your insights on global migration and climate today.

Kayly Ober: Thank you, Greg for having me.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One we’ve been talking about climate migration and displacement. Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe to our podcast on Apple or wherever you get your pods.Talking about climate can be hard-- but it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review if you are listening on Apple. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Brad Marshland is our senior producer; our producers and audio editors are Ariana Brocious and Austin Colón. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Our team also includes consulting producer Sara-Katherine Coxon. Our theme music was composed by George Young and arranged by Matt Willcox. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.