2021: This Year in Climate

Guests

Kathy Baughman-McLeod

Jay Inslee

Carla Frisch

Sasha Mackler

Beth Osborne

Rich Thau

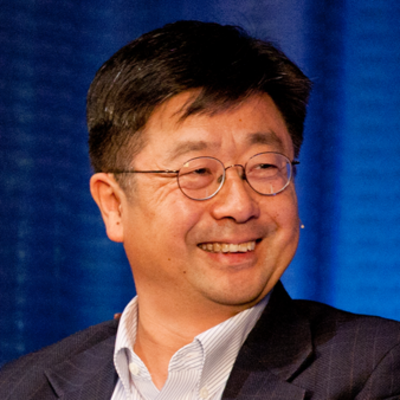

Jiang Lin

Albert Cheung

Amanda Machado

Katharine Hayhoe

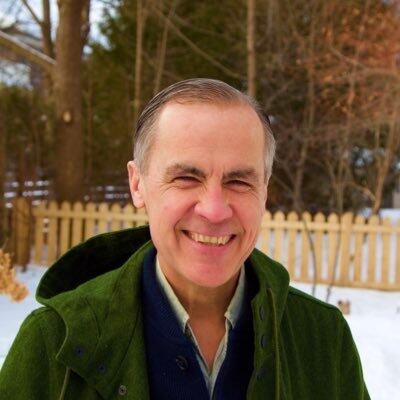

Mark Carney

Sister True Dedication

Summary

From extreme weather events to COP26 in Glasgow to the passage of the bipartisan infrastructure deal, 2021 has been a banner year. In this special year-end episode, hosts Greg Dalton and Ariana Brocious review the top climate news from the last year.

2021 started out on a positive climate note with the inauguration of President Joe Biden, who fulfilled campaign promise of rejoining the Paris Climate Accords on his first day in office. Biden made notable appointments to his cabinet, including familiar names like John Kerry and Gina McCarthy, as well as new names: appointing Michael Regan to head the U.S. EPA and Deb Haaland as the first Indigneous Secretary of the Interior. Biden started his term with a flurry of climate friendly executive orders and bold plans.

But it took most of the year for Congress to hammer out the details and finally pass the $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure law, which puts money into upgrading the electric grid, public transit, building out rail and EV charging stations, and climate resilience.

“This is a really big deal not only for energy and climate, but for the infrastructure system and for the larger, for the economy generally here in the U.S.,” says Sasha Mackler, executive director of the Energy Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center. “We finally got this bill across the finish line, and it really does represent a step change in our public commitment to many parts of the economy, but especially for climate change."

However the law still puts much more money into highways than climate friendly- initiatives, and it lost some climate programs in the negotiation process. Most of the money for the rest of President Biden’s climate agenda lies within the Build Back Better Act, still fighting its way through Congress.

On the bad news front: ahead of the COP26 international climate summit, the IPCC’s AR6 summary report showed the world on a path to blow past the target limit of 1.5°C of global warming. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called the report “code red for humanity.”

World leaders met for a week in Glasgow, Scotland, where – amid protests from climate activists and presentations from leaders of the Global South – they made some additional emissions commitments, including a pledge to significantly reduce methane emissions and to raise ambition at next year’s meeting. But at the last minute they also weakened the language around moving away from coal.

“I feel very positive about the outcomes from Glasgow. It's never enough. I think there will be a lot of people who are disappointed in some aspects of it, but... good progress was made,” says Albert Cheung, Head of Global Analysis at Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

While the concept of loss and damage made it onto the COP agenda this year, no significant moves were made, even in a year when climate impacts seemed to hit home here in the U.S. and abroad.

From wildfires to severe flooding to hurricanes and extreme heat -- it seemed as if every part of the country felt climate disruption at their front door. The concept of climate anxiety and grief are entering popular discourse, as many of us struggle to comprehend the current and future impacts of our carbon effects on the planet.

Yet amid all the news, climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe says hope about our collective future “begins in a dark place.”

“It begins by looking our crisis right in the face and recognizing it is really bad. It’s probably worse than scientists say. And there is no guarantee of a positive outcome,” Hayhoe says. But she recommends focusing on hope by being inspired by others’ actions and taking our own.

“We pick ourselves up and we keep on going because what is at stake is too valuable to lose. It's not our planet itself; it will orbit the sun long after we’re gone. What’s at stake is literally us.”

Related Links:

What the Infrastructure Deal Means for Climate

Taking Stock of COP26

Katherine Hayhoe on Hope and Healing

Extreme Heat: The Silent Killer

Mark Carney, Fatih Birol and the Narrow Path to Net Zero

Jay Inslee, BP and Washington’s Climate Story

Which Way Are Swing Voters Swinging on Climate?

Zen and Coping with Climate

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I'm Greg Dalton. From extreme weather events to the Climate Summit in Glasgow to the passage of the bipartisan infrastructure deal 2021 has been a banner year.

Jay Inslee: The most fundamental change that has occurred is that people are now realizing the threat to their personal hopes and dreams.

Greg Dalton: New report shows the world on a path to blow past the target limit of 1.5°C of global warming.

Mia Mottley: For those who have eyes to see. For those who have ears to listen, and for those who have a heart to feel... 1.5 is what we need to survive.

Greg Dalton: But 2021 also showed a few glimmers of hope.

Sasha Mackler: We finally got this bill across the finish line, and it really does represent a step change in our public commitments to many parts of the economy, but especially climate change.

Greg Dalton: This Year in Climate. Up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. As 2021 comes to a close, Climate One producer Ariana Brocious and I are taking a look back at the year from a climate perspective. Hey, Ariana.

Ariana Brocious: Hey, Greg.

Greg Dalton: Before we start, I just want to thank you for all the great work you’ve done this year. You’ve done some interviews people heard you on the radio show on the pod. It’s great to have you on the team. I’m really looking forward to having this conversation with you.

Ariana Brocious: Well, thanks. It’s actually a really nice chance for me as somebody who’s, you know, editing the show and the interviews most of the time to take a step back and reflect on what we’ve talked about and people we’ve talked to. So, I’m pretty excited about it too.

Greg Dalton: Well, it’s great to have you and 2021 has been a crazy year.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, I'm afraid we’ve gotten to the point where every year is kinda of a crazy year now. But it did feel like this year is a turning point when climate disruption really hit home for a lot of people. Virtually every part of the country felt the effects. Some people got unprecedented heat waves, there were fires and floods.

Greg Dalton: Right. In a recent poll from the Yale program on climate change communication says that for the first time a majority of Americans say they felt personally the effects of the climate crisis in their lives.

Ariana Brocious: So, this year what did you personally experience?

Greg Dalton: I experienced anxiety over things that happened and that didn't happen. I was worried about wildfire smoke here in California even when there were blue skies. One point I went rafting in the summer with my family in Idaho down the Salmon River we were driving back across Oregon the sky was really dark because of the Bootleg Fire a little south of us in Oregon. And we drove into this county where an evacuation order had been given and our phones started screeching saying get out. And it was wild to me that somehow the cell phone company knew that we were driving into a county where an evacuation order had been issued. One thing that really was a gut punch for me was the family mother and father and an infant and their dog who died hiking in the Sierra foothills. Climate was initially suspected maybe it was algae, investigation found out that it was dehydration. People are not used to how hard it is and they didn't have enough water.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, I live in Arizona, Southern Arizona and so unfortunately that does happen here every year. It's not as out of the ordinary, but to hear it happen in a place like the Sierra was pretty surprising to me too, I think. And, you know, you talked about this earlier this year in an interview you did with Kathy Baughman McLeod, Director of the Atlantic Council's Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center. Let’s hear a bit of that.

Kathy Baughman-McLeod: One of the misconceptions is it’s the hot places. But really it's the places least accustomed to heat who are least prepared to withstand it. And the number of days at a certain temperature threshold just continues to grow and you can look at Miami and say the number of days at what feels like 105°F is growing from I think it's 17 days to 45 days. In the climate scenarios you see those days rising to where a third of the year people are experiencing 105°. But if you live in Minnesota you are not accustomed anywhere near 105° and so a lot of heat planning and addressing extreme heat it’s about the human body. Your underlying conditions, your age, the elevation, the humidity, pollution, all sorts of things factor into the way humans experience heat.

Greg Dalton: An update from the U.S. EPA shows that heat waves in major cities occurred three times as often in the 2010s as they did in the 1960s and heat waves are becoming more frequent. If the data is so clear and it happens, why don’t we have a handle on it?

Kathy Baughman-McLeod: Well, the data is clear that it's getting hotter. And the way our cities are built is not helping. So, we have the urban heat island effect we have asphalt that absorbs heat and then it emanates at night. We have the they call it the diurnal range you know the range of temperature from the daytime to the nighttime it’s shrinking. The human body rests, and cleanses the brain at night and when you have temperatures still high at night we don't rest and we wake up tired and we make mistakes and hurt ourselves at work and things like that. I think we also don't have a handle on it because there is still this lack of data that I referenced just a minute ago of really understanding yes, it's hot, but then how does it play out. We've read a few stories about how the airplanes in Phoenix can't fly when it's a certain high temp and how many days do we expect that that will happen and what is that economic impact that it has. We don't really have those numbers either. So, how much is the cost to have a heat wave or to prepare for one or to respond to one. Those are all things that we need suss out.

Greg Dalton: And some cities are prepared, you expect Houston and Miami to be really hot and you said the people there, kind of accustomed to it. What about cities that, you mentioned Minnesota, that are less accustomed to heat waves and the population is less accustomed to living through them and knowing what to do and how to hydrate and when to go to a cooling center or what to do outside or not do outside.

Kathy Baughman-McLeod: You’re exactly right. And those populations, they need that education and they need to build that culture of preparation that we've built for hurricanes and fires. And I think that’s really clear on how to do that. We think that naming and ranking heat waves is a good way to do that to trigger those behaviors and to bring in all of those interventions. When the UK last summer lost 2500 people to heat, they put out a new heat health warning system and it failed because it came out too late. And so, for certain people with certain medical conditions 16 hours or 10 hours makes all the difference. And if the warning doesn't come out in time, people die.

Greg Dalton: We recorded that conversation at the beginning of June months before the Pacific Northwest saw its unprecedented heat wave where it hit 116° in Portland, Oregon. They're not ready for that.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, it was absurd. I mean the temperatures are just incredible and Kathy Baughman McLeod was exactly right it’s those areas that have been really unaccustomed to extreme heat that suffered the most. We saw that this year.

Greg Dalton: And it’s not just the direct effects of heat for every degree Celsius warmer the air holds 7% more water, which means stronger hurricanes and unprecedented flood.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, this year in the Southwest, yeah, you mentioned the climate impacts you've been feeling and this year in the Southwest we had a pretty interesting summer. Last summer in 2020 we had no rain, none of our usual monsoon rain. This summer we had I think the third wettest year on record which was amazing on the one hand, because it was great. The desert always loves getting rain. All of our washes were flowing and our vegetation was so lush. But it was also kind of scary at times because some of the storms that came seem to me to be even more intense than they normally are. And I wondered if that was another impact of climate where they’re becoming more intense, more quick hitting. Flooding is a pretty big danger for a lot of people too. And that also happened ironically, or perhaps not this is just the new reality we live in, in a year when we saw some of the first major cuts to water supplies from the Colorado River, which impacts a huge swath of the Southwest.

Greg Dalton: It’s hard to get our heads around the extremes of too much and too little. It's like it's hard to process all of that too much rain here and then all of a sudden, yeah, it’s these extremes that scientists have been warning us about. This year, we’ve also talked about human’s relationship with wildfire and the debate over pipelines like Line 3 which despite ample opposition did get built and put into operation this year.

Ariana Brocious: But, you know, our conversations weren’t always about doom and gloom. We also talked about some solutions and for example, we had this really fascinating conversation with inventor and entrepreneur Saul Griffith. And he told us that by electrifying everything we would only need about 40% of the total energy we consume now. That's one of those figures I've just been sharing with friends and family cause I'm still amazed by that number.

Greg Dalton: Me too. The idea that if we electrify everything our homes and mobility we can use less energy.

Ariana Brocious: Greg, you mentioned at the start of our conversation that for the first time in history, a majority of Americans surveyed now report being personally affected by climate disruption. So, are we seeing any evidence that that awareness is translating into political action?

Greg Dalton: It is certainly translating into awareness. The polls show that Democrats are getting more concerned. Unfortunately, Republicans are less concerned than they were some years ago with the caveat that it's always hard to assign direct causality. I'd say that awareness is translating into pressure on three levels. The regional, the national and the global. Great example when the regional level was Washington State, which had previously tried and failed to put a price on carbon pollution in 2016 and again in 2018 when it was defeated in part by a $30 million campaign that BP and other oil companies waged. But this year BP and other former opponents of climate policy came on board, along with environmentalists and tribes. I asked Gov. Jay Inslee why this coalition of previous foes came together to support Washington's cap and invest bill.

Jay Inslee: Well, the world is changing and thank goodness. It’s not changing -- in one sense it’s changing too fast, which is the biological collapse of the systems we depend on as humans. It’s going way too fast that way but it was also changing on the momentum we have to attack the first problem. And that is changing like weekly in the United States and it’s a good thing. Now, unfortunately, it has taken massive forest fires, billions of clams and mussels being cooked in their shells. Ocean acidification, sea level rise, hurricanes, tornadoes, floods in Germany and China to bring the increased public consciousness. So, the public’s consciousness is changing on this dramatically in the last several years. And organs of government and business are responding to that including BP to some degree. So, the most fundamental change that has occurred is that people are now realizing the threat to their personal hopes and dreams. That's the fundamental change. And the reason they're realizing that it is no longer an abstraction, you know, in 1998 or 1999 when I invited Al Gore to come give his presentations to my colleagues, it was a graph, right, we had a graph. Now it's a picture of dead coral all around the world from warming and acidification. And so, people are experiencing this visually in their own lives, and that is fundamentally changing this and that's why we have to be aggressive, assertive, take no prisoners and persevere. And that’s what we have brought to the table as well.

Greg Dalton: Many people the climate situation is so urgent that it requires bending rules, breaking norms, shaking up this status quo that rests on fossil fuel, capitalism, democracy is slow, by design. And there’s a growing group of people who think incremental change within the existing establishment is not going to get the job done.

Jay Inslee: Listen, an attitude of disrupting the status quo is a necessary survival mechanism for the human species right now. We are waking up every morning figuring out how can I disrupt the status quo. Because the status quo is deadly, it’s fatal, it will destroy economies and the biology that we exist on. So, that attitude is an appropriate one, but we can get this done while still maintaining our democratic traditions.

Greg Dalton: And you said earlier that BP has changed a little bit. Do you welcome having oil companies on your side and now on this climate bill it strikes me as odd that oil is on board and Republicans aren't. That's an interesting picture.

Jay Inslee: As Lincoln said, as our case is new, we must think anew. And yes, we should welcome people who agree with particular strategies going forward and BP may disagree with other ones; that should not stop us from working to pass good policies in my book. The situation is too dire not to welcome any effort to try to pass good climate legislation. We don’t have the luxury of sort of dividing the world into two camps here.

Greg Dalton: Right. It’s what things used to do is cut deals with people you don't agree with --

Jay Inslee: The good old days.

Greg Dalton: Right, yeah.

Jay Inslee: It’s called democracy.

Ariana Brocious: Greg, back in 2019 Washington Gov. Jay Inslee campaigned to be the Democratic nominee for president. And he campaigned as the climate candidate. His campaign then didn't really get much traction. But what of those ideas of his do you think have made it into the national discourse?

Greg Dalton: Well, Inslee and to a lesser extent Tom Steyer were driving climate issues during the campaign. Remember we had this amazing moment where they’re competing over how many trillions of dollars, they’re gonna invest in climate, something we had never seen before. Climate never played that level of prominence in a presidential campaign in 2012 and ’16 it was basically invisible during the campaign. In addition to really bringing climate to the center of the agenda and really getting some of those ideas and people into the Biden campaign. I think one of Inslee’s lasting contributions was the brain trust from his campaign formed Evergreen Action policy advocacy group that is influencing policy today long after the presidential campaign of Jay Inslee has ended. But just as the situation in Washington State shifted enough for Inslee to get his legislation through in the state level on the national level we did see President Biden kicking off his term with a flurry of climate friendly executive orders and probably most significantly, were the people he brought into his administration, really brought the A-team.

Ariana Brocious: Right. Because personnel is policy, right?

Greg Dalton: And he brought back some veterans, John Kerry, Gina McCarthy, plus new voices and players. Michael Regan, the first black man to head US EPA and Deb Haaland. Major deal, the first Native American secretary of the interior presiding over an agency that has done a lot of terrible things to indigenous people in our history. And on the legislative front, we just saw the passage of the bipartisan infrastructure deal.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, let’s talk about how big of a deal this new infrastructure law could be for climate. There's still a lot more money for highways than for climate friendly initiatives. We’ve got about 110 billion of new spending for highways, roads and bridges and only $39 billion for public transit.

Greg Dalton: Right. But there are 65 billion for grid upgrades which will help renewables, some of which will go into EVs. $7 billion for EV charging and 47 billion for climate resilience for the first time and 66 billion for rail. But a lot of how all this money will be spent is up to the states. So, the actual impact on climate isn’t baked in.

Ariana Brocious: Let’s listen to a bit of our recent episode on this. You had a conversation with Carla Frisch, Principal Deputy Director of the office of policy at the US Department of Energy. Sasha Mackler, Executive Director of the Energy Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center and Beth Osborne, Director of Transportation For America.

Greg Dalton: Right. I started by asking Sasha Mackler how big a deal is the long-awaited infrastructure act.

Sasha Mackler: This is a really big deal not only for energy and climate, but for the infrastructure system and for the larger, for the economy generally here in the US. We've been waiting for I would say more than 20 years for an infrastructure bill; seems like every week has been infrastructure week for a very long time. And we finally got this bill across the finish line, and it really does represent a step change in our public commitment to many parts of the economy, but especially for climate change.

Greg Dalton: Beth Osborne, you issued a statement after passage of the infrastructure act saying “It will fail to produce meaningful shifts on climate and equity.” Why do you say that?

Beth Osborne: Well, the change in the bill on the vehicle side is wonderful and exciting, but it's very status quo on the transportation program. It has taken a decades-old transportation program that's produced very poor results in both equity and climate, but also in safety in terms of building local economies in terms of dividing, usually black and brown communities in terms of giving people equitable access to jobs and services in terms of costing people a lot of money. It's performed very poorly in all of those areas, and we're hoping for a different result from basically the same programs. Now, that's gonna depend on exactly how aggressive US DOT is in using their administrative capacity and authority. And it’s also gonna depend on how much each of the 50 states wishes to change their behavior and investment.

Greg Dalton: Okay. So, yeah, states get a lot of say in this. So, Carla I recognize you are with the Department of Energy, not the Department of Transportation, but can you respond to what Beth says there.

Carla Frisch: One thing Beth is pointing out is this is one step of investment. So, we got the bipartisan infrastructure law, which has passed and been signed by the president and we are very excited about. And then the second piece is the Build Back Better Act, which just passed out of the house and that includes additional investments. But today I think we’re talking about the bipartisan infrastructure law and I will point out it makes the largest federal investment in public transit in history and the largest federal investment in passenger rail since the creation of Amtrak. And really significant investments in EV both the charging and also at DOE on the supply chain for electric vehicles.

Greg Dalton: Beth Osborne, your organization says that states often choose to spend federal dollars on expansion over highway repairs. It’s more appealing for a politician to cut a ribbon or point to a new highway than it is to a repaired bridge or perhaps a scheduling system for a transit agency. Is this time any different? Is there gonna be a bias toward expansion over repair?

Beth Osborne: I certainly think we can all hope that everybody woke up the morning of the signing of the bill and was transformed by the hope for the future. But in my experience, they need a little bit of a push in that direction and this bill offers none. In fact, this effort rejected an effort on the House side to say that before a state could build new capacity, they had to demonstrate they had a plan for maintaining it along with the rest of their system. We require that on the transit side on the highway side we have and we continue to allow a state to say we have no idea how we'll maintain it and we're going to give up on other pieces of infrastructure and that has been maintained. The fact of the matter is that this and approach to transportation will invest a historic amount of money in transit and a historic amount in highways in the 1950s approach has never produced the results that we are hoping for. We really need to invest according to a goal or an outcome not just according to pouring amounts of money in individual pots. That's not how people travel and the climate gods will not care that this was a historic amount of transit funding if the historic amount of highway funding results in greater emissions.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One and we’re reviewing the year in climate. If you missed a previous episode or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods. Coming up we’ll dig into what happened on the international level.

Albert Cheung: I feel very positive about the outcomes from Glasgow. It's never enough. I think there will be a lot of people who are disappointed in some aspects of it, but... good progress was made.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. And today I'm joined by Climate One producer Ariana Brocious.

Ariana Brocious: 2021 actually started on a pretty positive note for climate. Joe Biden rejoined the Paris agreement as he had promised on day one of his presidency and that was a good moment.

Greg Dalton: Right. And we’ll dig into the significance of that in a moment when we talk about COP26, the international climate event of the year. But I think what really sets the stage for that summit in Glasgow was the report known as AR6 or assessment report six which the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released at the beginning of August.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, this is the report that probably a lot of people heard about because UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called it code red for humanity. And the report is pretty bleak. It says that sea level rise will be worse than previously expected, adding about a half a foot or more to earlier projections. And in all of the five scenarios that they studied the earth reaches the threshold of 1.5°C warming by 2040. That's only 19 years from now.

Greg Dalton: Yeah. And despite the grim news and screaming headlines about that code red for humanity, those findings didn't reach everyone. The week that report came out I interviewed Rich Thau of the Swing Voter Project and asked him if swing voters are hearing those alarm bells.

Rich Thau: They’re really not, Greg. And the focus groups that we did on August 10th certainly confirm that. We had 13 Trump to Biden voters, people who voted for Trump in 2016 and then Biden in 2020. And only three of them had heard the news, which had come out the day before about the IPCC report. So, for us there was not deep penetration into their psyche about what was happening and what seemed to me to be pretty major news like a huge amount of airplay and print play the day before. They seem to be missing some of the biggest news stories that are out there. And last month for example, I asked about what was happening with the transportation bill winding its way through Congress. And most of them hadn't heard that there was such a bill going through Congress. So, for me, this becomes sort of one dispiriting conversation after the next. We realize that certain things don't get through, but certain things do get through. For example, all the respondents a month ago back in July knew that a building had collapsed in Surfside, Florida. So, that hadn't escaped their notice at all, but some of the big longer-term issues, the things that have great political relevance like how many trillions of dollars Congress is going to spend on infrastructure for example, they're not paying close attention.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, TV is drawn to those dramatic stories. In the focus group you played a two-minute clip from the CBS evening news that highlighted the recent UN report as code red for humanity. Let’s hear that clip.

Male Speaker: Scientists say the planet is warming faster than at any time in at least 2000 years.

Female Speaker: Climate change is a problem that is here now. Nobody's safe and it’s getting worse faster.

Greg Dalton: Clip goes on with greater detail laying out the evidence. Well, first of all Rich, this was on mainstream network news yet it seemed like very few people knew about it.

Rich Thau: Yeah, we had people say, for example, well, I don't have time to watch the nightly news. People who said they heard little strands of this information here or there but they hadn’t heard a report like this one that pulled it all together. So, to me I think that's also part of it is that they're hearing individual notes but they’re not hearing the whole song.

Greg Dalton: Right. There was one respondent who said he had heard about drought in the West, but he hadn't heard about floods in the East. They haven’t kind of put together the whole country. One of your panelists Greg L from Pennsylvania said he saw the headline but intentionally did not want to learn more. Let’s listen.

Greg L: Come to think of it, I did see that on CNN. And it did sound pretty bleak. It did kind of give some hope but it sounded like we were far, we are closer to the pivot point than we thought. It’s accelerating more rapidly so I didn’t want to read the article.

Rich Thau: Didn’t want to read the article, Greg, news was too bleak.

Greg L: Too bleak, yeah. With all that’s going on I don’t need any more.

Greg Dalton: So, let’s get to that. How do emotions play into news that gets through and what doesn’t?

Rich Thau: One of the questions I thought was or sort of answers to the questions I felt were most interesting had to do with sort of emotionally how they deal with this. And I ask people which of three categories they fell into whether hearing this kind of news caused them to want to take action. And four of them said that. Three of them said it immobilized them. That they had found it so overwhelming they couldn’t react. And then six of them said they basically avoid it. So, we got 4 out of 13 basically who are responding. And by the way, the way those people respond is to find plants they don’t have to water as much in their garden, buy more sustainable products, not buy things with palm oil for example. This was the examples we heard in recycling of course, recycling always comes up as the way people contribute and try to deal with climate change. So, again you look at the totality of what people do or say they do or are willing to do. And frankly, in my estimation, it doesn't add up to a whole lot.

Ariana Brocious: And, you know, I think a lot of people regardless of where you sit on the political spectrum can relate to one of those emotional reactions, right, especially feeling immobilized I think that's pretty common when you get overwhelmed by all the climate news. So, Greg, how much do you think what swing voters pay attention to really matters in the fight against the climate crisis?

Greg Dalton: Well, I think there's a real disconnect. On the one hand, whom we elect really matters, those swing voters have a disproportionate impact on our national politics. We have the technology to dramatically cut carbon emissions and yet the popular will doesn't translate, isn’t reflected in congressional action. People support climate action but that’s not happening in Congress, which is heavily influenced by fossil fuel interests who are slowing things down. We have a cash and carry Congress. On the other hand, business and industry are moving faster than governments and all those actions matter far more than whether we use plastic straws or recycle. The cheapest electricity on the planet these days comes from wind and solar renewables are winning they’re no longer more expensive than conventional electricity. So, the markets are very powerful and moving.

Ariana Brocious: Right. Domestic government is not really moving as fast as a lot of people would like. And that’s true on the international level as well. In November we saw the 26th convening of the conference of parties known as COP26 this year it was in Glasgow. And let’s listen back to a bit of your conversation with Jiang Lin, an Adjunct Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who focuses on China's energy and climate policy. And Albert Cheung, Head of Global Analysis at Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

Albert Cheung: I feel very positive about the outcomes from Glasgow. It's never enough. I think there will be a lot of people who are disappointed in some aspects of it, but... good progress was made. I would say, if you zoom out a little bit, we now have commitments that could potentially get us on a track towards 1.7-1.8 degrees Celsius of global warming at the most optimistic end of the estimates, if all of the pledges are delivered on time and in full, including the long range ones out to 2050 and 2060, and that's not enough to get to 1.5, but it is a whole lot better than we were a couple of years ago, a little bit better than we were two weeks ago, and I think something that should not be taken lightly, because that is a lot of work that's gone into those negotiations to make that happen. And importantly, one key provision that says that we're all gonna come back in a year's time and do it again, and look at our commitments again and see if we can raise ambition again next year towards 1.5. I think that gives some hope that we can get an even better outcome in the next 12 months.

Greg Dalton: Right, the countries will be meeting in Egypt next year rather than waiting for five years, shortening those check-in time frames. Jiang Lin, what do you think is the big takeaway, the outcome from Glasgow?

Jiang Lin: Well, I think COP26 made significant progress towards addressing the urgency of climate change, however, there's still a major gap left to fill as Albert recognized already, if you add a long-term target, you might get us to 1.8 degrees Celsius. However, if you count the near-term actions by 2030 we’re probably at 2.4 degrees Celsius, so that's a major, major gap. However, the COP26 does recognize the need for ambitious action in the next decade, so we're not only looking at long-term target towards 2050, 2060 etcetera, but rather we have to cut emissions almost by half by 2030. I think that's an extremely important advance and I also think COP26 enhanced our goal to hold down to 1.5 degrees instead of a weaker language in the Paris Agreement. I think that's really important and recognize what science tells us to do, that's a minimum threshold to avoid disastrous consequences of climate change. Just another signal to that is, even though there was a last minute, so-called a watering down of the language on coal power, but nonetheless, this is the beginning of the end for coal power.

Greg Dalton: I'd like to play two clips from the conference. First, the Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley.

Mia Mottley: For those who have eyes to see. For those who have ears to listen, and for those who have a heart to feel... 1.5 is what we need to survive. Two degrees is a death sentence, for the people of Antigua and Barbuda, for the people of the Maldives, for the people of Dominica and Fiji, for the people of Kenya and Mozambique. And yes, for the people of Samoa and Barbados. We do not want that dreaded death sentence, and we've come here today to say try harder, try harder.

Greg Dalton: And here's Ugandan activist Vanessa Nakate.

Vanessa Nakate: I hope you can appreciate that where I live, a two-degree world means that a billion people will be affected by extreme heat stress. In a two degrees Celsius world, some places in the global south will regularly reach a wet bulb temperature of 35-degree Celsius. At that temperature, the human body cannot cool itself by sweating. At that temperature, even healthy people sitting in the shade will die within six hours.

Greg Dalton: Really powerful human statements of what's really at stake. You know, 1.5 or two degrees are not some abstract numbers. So Albert, despite progress being made, what was it like there to be with so much at stake and hearing statements like those?

Albert Cheung: These conferences of the parties, as they’re called, these COPs, are really unlike any other conferences that I for one attend. Normally, we're doing industry gatherings thinking about how to deploy clean energy, how to deploy electric vehicles and hydrogen. At COP, it is a rainbow. It is an incredibly diverse place to go where you have people from every country, all demographics, all ages, civic society, activists, NGOS and business, of course, and it is for better or for worse, this incredible show and circus where the spotlight is on the global climate community just for those two weeks. And first of all, you cannot but feel energized and feel an incredible sense of purpose when you're there, but secondly, I think that theater, those incredibly powerful speeches that we've just heard are a really important part of the process, and because the way that the Paris Agreement is structured, the way that these talks are structured is through this process of kind of moral pressure on countries to do the right thing. Powerful words really do matter because that's what motivates leaders. They don't wanna go back to their country and face their people having been the bad guy in the room, so I think those words really, really matter and really resonate.

Ariana Brocious: And even with the good news that came out of COP which Albert Cheung and Jiang Lin mentioned it was largely viewed as a disappointment by many people. And we should point out that even though the US was back at the table political pressures at home meant it couldn't commit to the coal or EV pledges that were made by other countries.

Greg Dalton: Right. Because Biden couldn't get his packages through Congress in time and there’s domestic resistance. There’s real questions about whether the US is really a climate leader and for how long it will be a climate leader. I think there's a lot of, people put a lot of hope on these COPs this Glasgow Summit think they’re gonna save the earth, and they are just one avenue of change.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, though, I will say one of the things that strikes me about the COP26 conversations is the talk of countries increasing their pledges. But there's a big difference between pledges and action. So yes, the nations of the world agreed to a 30% cut in methane emissions by 2030. That's a big deal, but even if that’s achieved that only shaves .2° off of our somewhat bleak future. And I hear Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley saying that a 2° rise is a death sentence for the most vulnerable countries. So, by not committing to stronger measures, did the less vulnerable nations effectively sign, somewhat of a death sentence for the most vulnerable?

Greg Dalton: Certainly, things in the Global South and developing countries are looking bad. They are more vulnerable and there is not a lot of generosity or compassion. Not only for the United States for foreign aid to helping other countries. We live very much in a kind of me first, you know, our country first political context. There’s not a lot of collaboration and we don’t seem to be learning the lesson that we’re all on this together whether it’s COVID we need to vaccinate the world and it’s climate we need to protect the world, we’re connected.

Ariana Brocious: And this year we saw at COP for the first time really talk about in a significant way this idea of loss and damage.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, previous pledges of money to be transferred from the north to south was framed as assistance with mitigation and adaptation, but loss and damage payments would be in addition to that.

Ariana Brocious: And that’s important because as Vanessa Nakate so aptly put it, you can't adapt to lost cultures and you can't adapt to starvation.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, she's amazing. And Vanessa is so powerful on this and it makes sense. If you spill sewage into your neighbor's property you're expected to pay for the damage and loss that you cause. It didn't make it into the final text of this year’s agreement, but momentum is building to address the responsibility of rich countries for damaging poorer countries. That's what happens with cities and states and individuals and companies. So, I expect we’ll be hearing a lot more about this at next year’s climate summit in Egypt.

Ariana Brocious: And the loss and damage conversation on the global level also mirrors what we talked about a lot on the show this year which is climate justice.

Greg Dalton: Yeah. When we talk about extreme heat, that affects people of color more. When we talk about infrastructure, which communities are helped and which are left behind. We talk about geoengineering we consider who gets to decide on the terms of the debate. Is it framed in a scientific technocratic way that rich countries look at it. Even when we talk about climate anxiety and climate-induced trauma, I’ve learned from talking to indigenous and people of color that their experience of compounding trauma began with colonialism and enslavement that began centuries ago. Only recently are white people like you and me coming to recognize this and feel it and sense it as real.

Ariana Brocious: And even when we talk about diet or access to nature our society is profoundly unequal.

Greg Dalton: Totally. And I particularly appreciate you highlighting that in your interview with Amanda Machado, a writer and facilitator, whose work explores how race, gender and identity affect the way that we experience the outdoors. Let’s listen to a bit of that.

Amanda Machado: White folks control 98% of land in the USA they own 98% of land in the US they control 80% of the wealth. They’re over 90% of the CEOs of companies that are in the outdoor industry and the environmentalism movement as well. So, when you have white dominance to that extent, then it makes sense that that's the narrative that is centered in what we hear about the outdoors what we hear about the environmentalism movement and what we think of as an outdoorsy person or what an environmentalist looks like. So, to me I think that's where I become really passionate about the work I do of forcing those organizations in that industry to start confronting white supremacy in a way that I don't think they wanted to for a really long time. You know, a lot of times what I get the impression of when I do work with these organizations is that there is a way that we can kind of avoid that subject, but to me, I feel like we cannot really hold ourselves accountable to the outdoors and to the environment unless we’re addressing that first it kind of becomes the core of all the other issues that we’re dealing with.

Ariana Brocious: So, how do those kinds of imagery and narratives then discourage people of color from taking part in wilderness activities?

Amanda Machado: Well, I think what I've noticed is that you know if you can't see yourself in those spaces then it’s hard to feel invited or welcome in that movement. And I think the other part that we really need to address is that there is a long history of trauma and oppression that connect the outdoors to people of color. We see this with black folks on slavery, indigenous folks in colonization. As a Latinx person I think a lot about how growing up from farming and being in touch with land and being outside was associated with migrant work and that was the kind of work that was the stereotype of the Latinx community that a lot of folks are trying to get themselves out of and show that we were educated and outside of that kind of realm of labor. So, when we have those associations in our history and in our ancestry, then it's hard to unpack all that and then reconnect with the outdoors in a way that doesn't feel oppressive and in a way that actually feels liberating. And, you know, couple that with how the history of that still lingers in outdoor spaces to this day I mean what I think about a lot is Oregon is what was the only state that explicitly excluded black folks from entering the state of Oregon when it was founded in its constitution that was it was a white supremacy state. Colorado had Ku Klux Klan members all throughout its government, when it was first founded. The highest hate crimes are still often in places that are outdoorsy, right, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming have some of the highest rates of hate crimes for queer folks or people of color in the United States. So, when you think about that long history, the fact that public pools, public beaches, public parks were all segregated until the Civil Rights Act it becomes even more clear that you know people of color were just never welcome in these spaces that trauma still exists. And unless we confront it, I think it's really hard to reengage with the outdoors in a way that feels healthy. I know for me when I grew up, I grew up in Florida and it was just pretty much standard that anytime I went to a park or an outdoor space there were Confederate flags all along the highway and all along the houses leading up to that space. So, to me that was just always part of the deal. I kind of accepted that to be outdoors and to share my love of the outdoors with other folks meant I had to access some of the most racist places in the United States, but I think that's a hard bargain to make and a hard bargain to ask folks of color to make. And I think that's what we’re grappling with right now.

Ariana Dalton: You're listening to a Climate One conversation reviewing this year in climate. Coming up we revisit conversations with UN climate envoy Mark Carney. Thich Nhat Hanh collaborator Sister True Dedication and climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe.

Katharine Hayhoe: We pick ourselves up and we keep on going because what is at stake is too valuable to lose. It's not our planet itself; it will orbit the sun long after we’re gone. What’s at stake is literally us.

Ariana Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I'm Greg Dalton. And today I'm joined by my colleague and producer Ariana Brocious as we review the top climate stories of the year.

Ariana Brocious: We talked earlier in the program about government action and inaction on the state, federal and international levels. But this year we also saw significant moments in the private sector, especially with major auto manufacturers pledging to stop making fossil fuel burning cars in the next 10 to 15 years. How big of a sea change do you think that is?

Greg Dalton: It’s huge. I think it’s removed some of the political opposition to climate policy that we’ve seen in recent years, and remember that the makers of gasoline cars would not be doing this without the innovation and disruption brought by Tesla. It’s the sixth most valuable company in the world. Just 10 years ago, Tesla was near death. It was barely making any cars and it survived thanks to a federal loan that was part of the 2009 stimulus package. The move of Ford, GM and VW and other automakers to EVs has ripple effects throughout other industries. Obviously, the fossil fuel industry doesn't want to see this but I talked with Mark Carney, the former central banker for both Canada and the UK who is now working to decarbonize the global economy. We talked about climate action and finance, and about the impact of three insurgent directors being recently elected to the board of Exxon Mobil.

Mark Carney: One of the things I thought is there is a return to shareholder value. If you Google engine number one Exxon presentations. So, this is the activist investor who started this process to get those directors elected. There is an 80+ page presentation which goes through basically, the outlook for value creation and the core thesis of it and backed up with some series of analysis of numbers, is that the company Exxon had not been investing enough in the fuels of the future or the energies of the future. And that plus the prospect of stranding of assets meant that it was destroying value and that it needed the strategic change. It's an interesting alignment I mean very important situation, but it's an alignment of value and the future value more consistent. I don’t want to oversell it, more consistent with sustainability as opposed to value in the past which was the existing strategy the company was pursuing.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, it’s about money rather than virtue. I’d like to play a clip from CNBC's Jim Cramer and get your reaction on the other side.

Jim Cramer: I’m done with fossil fuels. I mean big pension funds saying this will not gonna work anymore. It doesn’t matter how good they are --

Female Speaker: Do you think that’s the biggest thing holding these guys back and not necessarily just oil production part here in the United States?

Jim Cramer: Absolutely. Look at BP, it’s a solid yield, very good. Look at Chevron buying back $5 billion of the stock. Nobody cares. And this has to do with new kinds of money managers who frankly just want to appease younger people who believe that you can't ever make a fossil fuel company sustainable. We’re in a deathknell phase.

Greg Dalton: That's quite a statement from a leading figure on Wall Street CNBC to say, and he sounds bitter about this change and he points to millennial money managers and investors in the deathknell phase. Your reaction.

Mark Carney: Well, it’s interesting, I hadn’t heard it. He often sounds bitter. I wouldn’t overstate. But, no, it is quite instructive. I would parse out a couple of things. One is that I wouldn't put this down to use the term woke capitalism. I put it down to you know an assessment of where the world is going or where the world needs to go. And a more extreme section of the economy that isn’t moving fast enough. Now, one of the challenges, I think we have is that within the energy sector there are companies that are transitioning there are companies that are trying to take now finally a significant proportion of their cash flows and do what engine number one wants Exxon to do in these new directors who want Exxon to do to reinvest in a renewable energy and transition from the fuels of today to those of tomorrow. So, now, identifying those true examples as opposed to the niche you know kind of trophy investments that are intended to appease this issue --

Greg Dalton: Greenwashing.

Mark Carney: -- yeah, as opposed to really truly transform. That’s what investors have to make a judgment about. So, I wouldn't have the blanket I’m done with the entire sector any more than I would in the steel sector, which of course is hugely polluting and emitting. But it will be a period of time will run there are certain companies that are investing huge amounts in greening steel. And we need a system we need objective judgments about who's actually doing it, but we need a system that gets capital to those companies so that they can actually make those investments and takes capital away or changes the pricing at least of the companies that aren’t doing anything or aren’t moving fast enough.

[Ariana Brocious: So, Greg do these conversations with industry leaders give you hope that the private sector can do what the public sector can't?

Greg Dalton: I'm decidedly schizophrenic when I hear things like that, I see lots of good things happening, well-intentioned people. Corporations are acting in their self-interest and those interests are starting to align with lower carbon because their shareholders and their employees are forcing them to go in that direction. I also am deeply skeptical about the rules of capitalism themselves and pushing pollution into the comments, privatizing the gains and I have some deep growing concerns whether capitalism will reform itself in time. So, sometimes I see hope with corporate action and sometimes I think the system is deeply broken, creating so much wealth disparity so much pollution and I doubt that it will reform itself in time.

Ariana Brocious: And speaking of hope, one of my favorite Climate One interviews that we did this year was the one with Katharine Hayhoe whose latest book is called Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World. And I’d say that this is a must-listen Climate One episode for anyone who wants to be better at talking about climate which is hugely important. But what I’d like to play today is how she responded to your question about hope.

Greg Dalton: Katharine, I want to ask you, your hope seems to be authentic. And I’m wondering though sometimes let’s be honest that climate is gonna continue to change during our lifetime. It's going to continue to get darker. The science tells us there is already a lot of momentum built up in the system. So, how do you acknowledge that it's going to get worse during our lifetimes. We can do a lot to reduce the harm and still maintain that hope. Do you have to like, do you embrace that inevitability and that darkness to get through to genuine hope?

Katharine Hayhoe: You have to. What I’ve learned is that whether you go to theology, philosophy, psychology or science, hope begins in a dark place. Hope begins with acknowledging just how bad it is. We’re not talking about a sort of a Pollyanna hope or a bury your head in the sand hope or a cultivate a positive attitude and everything will work out okay hope. We’re talking about real hope, muscular hope, rational hope. It begins by looking our crisis right in the face and recognizing it is really bad. And as we talked about at the beginning it’s probably worse than scientists say. And there is no guarantee of a positive outcome. In fact, a negative outcome is more likely than a positive one. But hope is that faint small bright light at the end of the dark tunnel, that we head for with all our might and all our strength and when we get dragged down when we get discouraged, when we get anxious and depressed, and believe me that happens to me too. We take a breath, we fix our eyes on that hope by going out and looking for what someone else is doing, or by making a choice to do something myself, and then we pick ourselves up and we keep on going because what is at stake is too valuable to lose. It's not our planet itself; it will orbit the sun long after we’re gone. What’s at stake is literally us. So, I think of Christiana Figueres, who of course shepherded the Paris agreement. If anybody could be hopeless, despondent and frustrated it’s her. Yet, she wrote this amazing hopeful book of what our lives would look like by 2030, with climate impacts. But if we had transitioned to clean energy, walkable cities, clean air, cheap electricity, ample food for all and she said, look at this amazing vision of the future. The biggest lesson we learned in 2030 looking back, was that we were only ever as doomed as we believe ourselves to be.

Ariana Brocious: That’s such a powerful line. Greg, listening back to that a few months later, what do you think about it? I mean Katharine acknowledges that a negative outcome on climate is more likely than a positive one yet she still finds this deep reservoir of hope.

Greg Dalton: Right. And we’ve seen in history that sometimes during the biggest battles or seizures people find purpose and a lot of motivation when times are tough. For me I think the question is how do we balance the psychological need for accepting the world situation with the urgency to do something. And researchers will say that doing something makes us feel better. So, action can induce hope it's not that I need hope to act. If you act you will be hopeful and you'll feel better. I struggle with the line between acceptance that the climate is going to get worse in our lifetime. We’re not gonna solve it, we're not gonna fix it. That's just a fact. And resignation is something that I don't want to do. It’s something I discussed at length with Sister True Dedication, a Zen Buddhist nun and editor of Thich Nhat Hanh’s latest book Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet. Internationally renowned Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh was a refugee from the Vietnam War when Martin Luther King nominated him for a Nobel Peace Prize for his work to end that war. A few years later he actively worked to rescue other Vietnamese refugees. I asked Sister True Dedication how that experience shaped his understanding of what he calls awakened action. I’d like to end today's show looking back at the year in climate with a section of that interview.

Sister True Dedication: I think around the time when Thay was calling for peace (so we call Thich Nhat Hanh “Thay” - it means teacher). When he left Vietnam to call for peace and actually that's what led to his exile, that he had dared to call for peace. And it was while he was traveling the world calling for peace that he became aware of the situation of the boat people. At the time he reflected something like this he said, if compassion doesn't lead to action how can you call it compassion? So, there’s really the sense in the whole of Thay’s life that compassion has to be expressed in the way we live our life, the way we speak, the way we act, the way we engage. So, compassion isn’t something that you cultivate in the sitting meditation position in a monastery or a temple, but it's something that should really be embodied with how we spend our time and energy.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, if action is healing, how does that apply to climate?

Sister True Dedication: So, for Thay, what contemplation, mindfulness and meditation have to do with the climate crisis is actually in this moment we all being called to a much deeper, braver awakening that hasn't happened yet. We have to really wake up to the severity of the situation and change our whole way of seeing and for Thay perhaps we could call it insight. We all need to get a certain insight and it’s the insight that we don't have and that’s why, you know, it’s so difficult to take action.

Greg Dalton: I often encounter people in the climate conversation who are so scared and so worried about the urgency that we must act quickly. I think people are so scared they think that any action is good action and other people will say, no, we need to slow down and think about more intentional action. But that seems hard to do when literally the earth, our home is on fire.

Sister True Dedication: I think even as Buddhists we acknowledge the urgency of the situation. The question is how do we respond to that urgency and how can we get the strength we need, the insight we need to not panic. And I think what happens to a lot of us in the urgency is we're in a knee-jerk mode, in a reactive state in our own lives, and just we really have to remember that the activists, the scientists, the people who are working in the forefront of tackling the climate crisis, we’re all human beings. And that urgency--we can't live in that state of heightened arousal, you know, it can destroy our body and mind. So, we are also part of the earth and so we want to contribute in such a way that is sustainable and healthy for ourselves while we act urgently. And the power of zen and the power of mindfulness is that it roots us in the present moment so we can be alert to what is going on. We can be responsive. We can be the master of our mind and awareness in any given situation. So, we can really have the present moment as the ground for our urgent action and that is action taken with clarity, with courage, with solidity, with freedom, and not with panic. And more deeply actually to lean into that fear and despair, and accept that it is very possible that we won't manage to turn this around. There’s a certain acceptance that can come with that and a certain, what Thay called peace and freedom. And it’s like, alright, well, what can we do anyway? We got nothing to lose because everything you know the odds may be stacked against us. And that can liberate us I think from the panic and the anxiety to have a kind of peace, of freedom. And then all the action can come from love. We’re not measuring the consequences of our action, we’re just human beings, part of all the species on this beautiful planet trying our best.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One, Ariana Brocious and I have been talking about this year in climate. Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe to our podcast on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Ariana Brocious is our producer and audio editor. Our audio engineer is Arnav Gupta. Our team also includes Steve Fox, Kelli Pennington, and Tyler Reed. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.