Taking Stock of COP26

Guests

Albert Cheung

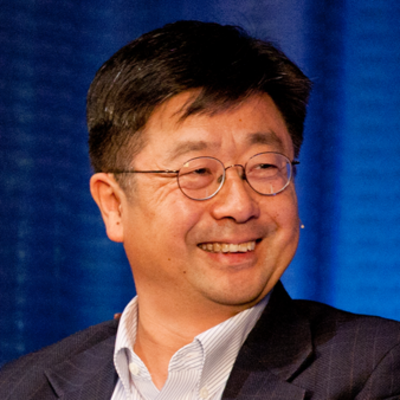

Jiang Lin

Vanessa Nakate

Summary

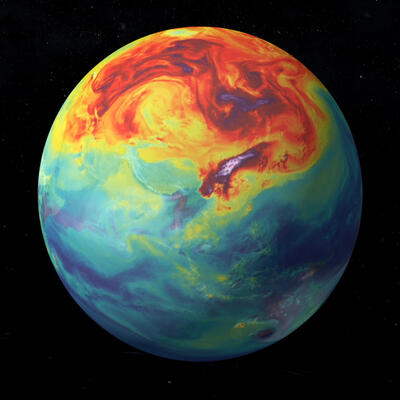

After two weeks of negotiations, presentations and protests in Glasgow, the huge international climate summit known as COP26 is over. World leaders met again to try to strengthen each other’s commitments to reducing emissions and staying under the 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming outlined in the Paris Agreement. But current commitments still fall short, says Jiang Lin, an adjunct professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

“If you add the long-term targets, you might get us to 1.8 degree Celsius. However, if you count the near-term actions by 2030 we’re probably at 2.4 degrees Celsius, so that's a major, major gap,” he says.

“It's never enough,” says Albert Cheung, head of global analysis at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, of the COP26 outcomes. “I think there will be a lot of people who are disappointed in some aspects of it, but good progress was made,” noting that current commitments still put the world in a slightly better place than it was before the conference.

“And importantly, one key provision says that we're all gonna come back in a year's time and do it again, and look at our commitments again and see if we can raise ambition again next year towards 1.5. I think that gives some hope that we can get an even better outcome in the next 12 months,” Cheung says.

Many leaders did agree to accelerate the phase out of coal, though Cheung says he was disappointed that the agreement didn’t include most of the major coal users like the U.S., China and India. And at the last minute, India and China stepped in to change the language from “phase out” to “phase down,” which many saw as another loss in the effort to quickly end our use of fossil fuels.

Separately, the U.S. and China announced a surprise bilateral agreement to work together on moving away from fossil fuels and stabilizing the climate, which Lin took as a good sign, especially considering the many tensions between the two superpowers at present.

"It shows that both countries recognize the threat of climate change to the world and to their own economies, and recognize the urgency to take so-called ‘enhanced action,’ not just business as usual,” Lin says.

He says another significant achievement towards quickly controlling temperature rise was the global methane pledge. “By some estimates, the pledge of 30% reduction of global methane emissions could in itself shave off 0.2 degrees Celsius in terms of warming by 2040 or so.”

Still, many of those from developing countries were disappointed to not get further on commitments from rich countries to pay for climate resilience and ongoing loss and damage caused by climate disruption.

Raising those issues is part of the focus of Vanessa Nakate, a young climate activist from Uganda.

“While Africa is on the front lines of the climate crisis, it’s not in the front pages of the world’s newspapers. We can change this simply by listening to the activists who are speaking up and amplifying their voices,” she says.

In her new book, A Bigger Picture, Vanessa tells about her journey from student to activist, inspired by Greta Thunberg, that has put her on stage with notable climate leaders from around the world.

“The people who really need to listen to my message and to my demands [are] really the people in power: the people who are continuing to construct oil pipelines, who are continuing to frack gas, who are continuing to open coal power plants while promising us net zero by 2040 by 2050 or by 2030,” Nakate says. “Leaders must understand that loss and damage is here with us right now.”

Related Links:

A Bigger Picture: My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis

COP26 final agreements

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. This year’s huge international climate summit is over. Did world leaders meet the challenge of keeping global temperature rise under 1.5 degrees?

Jiang Lin: If you add a long-term target, you might get us to 1.8 degree Celsius. However, if you count the near-term actions by 2030 we’re probably at 2.4 degrees Celsius, so that's a major, major gap.

Greg Dalton: But there were important outcomes from the meeting.

Albert Cheung: It's never enough. I think there would be a lot of people who are disappointed in some aspects of it, but good progress was made.

Greg Dalton: And are the voices of the Global South really being heard?

Vanessa Nakate: While Africa is on the front lines of the climate crisis it’s not in the front pages of the world’s newspapers. We can change this it’s simply by listening to the activists who are speaking up and amplifying their voices.

Greg Dalton: Taking Stock of COP26. Up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. After two weeks of negotiations, presentations and protests in Glasgow, COP26 is a wrap. On today’s show we’ve invited a couple of guests to help unpack what was achieved - and what wasn’t - at the international climate summit. Jiang Lin is an adjunct professor at the University of California, Berkeley, focused on China’s energy and climate policy. Albert Cheung is head of global analysis at Bloomberg New Energy Finance. We jumped right in to discuss how much progress was really made this year.

Albert Cheung: I feel very positive about the outcomes from Glasgow. It's never enough. I think there will be a lot of people who are disappointed in some aspects of it, but... good progress was made. I would say, if you zoom out a little bit, we now have commitments that could potentially get us on a track towards 1.7-1.8 degrees Celsius of global warming at the most optimistic end of the estimates, if all of the pledges are delivered on time and in full, including the long range ones out to 2050 and 2060, and that's not enough to get to 1.5, but it is a whole lot better than we were a couple of years ago, a little bit better than we were two weeks ago, and I think something that should not be taken lightly, because that is a lot of work that's gone into those negotiations to make that happen. And importantly, one key provision that says that we're all gonna come back in a year's time and do it again, and look at our commitments again and see if we can raise ambition again next year towards 1.5. I think that gives some hope that we can get an even better outcome in the next 12 months.

Greg Dalton: Right, the countries will be meeting in Egypt next year rather than waiting for five years, shortening those check-in time frames. Jiang Lin, what do you think is the big takeaway, the outcome from Glasgow?

Jiang Lin: Well, I think COP26 made significant progress towards addressing the urgency of climate change, however, there's still a major gap left to fill as Albert recognized already, if you add a long-term target, you might get us to 1.8 degrees Celsius. However, if you count the near-term actions by 2030 we’re probably at 2.4 degrees Celsius, so that's a major, major gap. However, the COP26 does recognize the need for ambitious action in the next decade, so we're not only looking at long-term target towards 2050, 2060 etcetera, but rather we have to cut emissions almost by half by 2030. I think that's an extremely important advance and I also think COP26 enhanced our goal to hold down to 1.5 degrees instead of a weaker language in the Paris Agreement. I think that's really important and recognize what science tells us to do, that's a minimum threshold to avoid disastrous consequences of climate change. Just another signal to that is, even though there was a last minute, so-called a watering down of the language on coal power, but nonetheless, this is the beginning of the end for coal power.

Greg Dalton: We'll get into that. I'd like to play two clips from the conference. First, the Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley.

Mia Mottley: For those who have eyes to see. For those who have ears to listen, and for those who have a heart to feel... 1.5 is what we need to survive. Two degrees is a death sentence, for the people of Antigua and Barbuda, for the people of the Maldives, for the people of Dominica and Fiji, for the people of Kenya and Mozambique. And yes, for the people of Samoa and Barbados. We do not want that dreaded death sentence, and we've come here today to say try harder, try harder.

Greg Dalton: And here's Ugandan activist Vanessa Nakate. We’ll have a longer conversation with her later in this episode.

Vanessa Nakate: I hope you can appreciate that where I live, a two-degree world means that a billion people will be affected by extreme heat stress. In a two degrees Celsius world, some places in the global south will regularly reach a wet bulb temperature of 35-degree Celsius. At that temperature, the human body cannot cool itself by sweating. At that temperature, even healthy people sitting in the shade will die within six hours.

Greg Dalton: Really powerful human statements of what's really at stake. You know, 1.5 or two degrees are not some abstract numbers. So Albert, despite progress being made, what was it like there to be with so much at stake and hearing statements like those?

Albert Cheung: These conferences of the parties, as they’re called, these COPs, are really unlike any other conferences that I for one attend. Normally, we're doing industry gatherings thinking about how to deploy clean energy, how to deploy electric vehicles and hydrogen. At COP, it is a rainbow. It is an incredibly diverse place to go where you have people from every country, all demographics, all ages, civic society, activists, NGOS and business, of course, and it is for better or for worse, this incredible show and circus where the spotlight is on the global climate community just for those two weeks. And first of all, you cannot but feel energized and feel an incredible sense of purpose when you're there, but secondly, I think that theater, those incredibly powerful speeches that we've just heard are a really important part of the process, and because the way that the Paris Agreement is structured, the way that these talks is structured is through this process of kind of moral pressure on countries to do the right thing, so I'm glad I was able to spend a couple of days there, it was a great privilege to be there. And I think that powerful words really do matter because that's what motivates leaders. They don't wanna be seen as the bad guy in the room. They don't wanna go back to their country and face their people having been the bad guy in the room, so I think those words really, really matter and really resonate.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I've been those where someone from an island nation speaks and it's just... you could hear a pin drop. And just because of the moral voice that's being heard, and some people would say that that's really what changed this time was the presence and profile of people like Vanessa Nakate and other youth who are really calling, and Greta, of course, really calling on the boomers and the people in power and shaming them in some cases, Jiang Lin... How did that hit you? These numbers matter, how do those statements or other cries for help from Glasgow land with you personally?

Jiang Lin: Well, I think that made it real for scientists like me to understand the consequences. Not on a global average mean temperature, but rather on people's livelihood, so that's an extremely, extremely powerful motivating factor. And that's why I think IPCC new report made a very strong directional signal that we have to go towards 1.5 degree Celsius goal, and that goal has been strengthened, our understanding of the consequences of climate change has been strengthened as well.

Greg Dalton: Albert, British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson was host of the Glasgow summit, he previously mocked eco-doomsters in some of his newspaper columns, but he's changed his tune, which he tends to do, but after the conference, he said it was the death knell for coal. As our resident Brit here, how do you see Johnson's handling of the conference?

Albert Cheung: First of all, if any politician who has previously mocked climate change wants to change that position, I'm all for it, so I wouldn't have previously supported what he was saying, but now I do... Look, the UK government had several really marquee goals for COP. One of them was to keep 1.5 alive. One of them was around coal and actually to accelerate the phaseout of coal. And so, I think two key things happened during COP. In the first week we had this global agreement on coal which was to accelerate the phaseout of coal. I would say personally I thought that was a slightly disappointing agreement because it didn’t actually include most of the major coal users out there like the US and China and India. But it did include a few European nations which hadn’t previously made such a pledge so that was a good step forward. And then of course the final text does have this language that says we all agree to accelerate the phasedown of coal. And I think as we’ve all heard now that language had previously said a phaseout of coal and India and China stepped in to say we don’t like phase out, can we please replace that with phase down which implies some continuing role for coal which as we all know is really not compatible with 1.5°. And that was a source of major disappointment to Alok Sharma, the COP president, and you could see on his face he was incredibly disappointed.

Albert Cheung: Yeah. And so, I think for the Prime Minister to say the death knell for coal I think the UK government was always going to trumpet the achievements of COP. And I think this is what we’re seeing now is maybe overselling a little bit what’s been achieved.

Greg Dalton: Jiang Lin, Xi Jin Ping did not attend the Glasgow conference, but the US and China announced a surprise bilateral agreement to work together on moving away from fossil fuels and stabilizing the climate and supports our economy and lifestyles, and will that result in meaningful emissions? We know that as we record this President Xi and President Biden are talking this evening. But tell us about that bilateral agreement.

Jiang Lin: Well, I think the fact that US and China made such a surprise announcement during COP, under the challenging state of US China relationship, is a story in itself, right? It shows that both countries recognize the threat of climate change to the world and to their own economies and recognize the urgency to take so-called enhanced action, not just business as usual. So, I think that means that both teams are working really, really hard to find a common ground amid tensions on multiple fronts. I think that's a very hopeful sign. As you remember it was the agreement between China and US back in 2014 that laid the foundation for Paris. So, obviously 2021 is not 2014 we are in a different world. But the common theme, both Special Envoy Kerry and Xie, made it clear that climate change is a common interest for both countries and they’re committed to take a much greater enhanced action in the next decades. Both words are key -- enhanced action and next decade. I think that’s the new focus.

Greg Dalton: Right, it seems like there's so much tension right now between the US and China over China's military expansion in the South China Sea, forced labor camps in Xinjiang, trade tensions, the suppression of civil rights in Hong Kong, it's a long list, but climate might actually be an area, Jiang Lin, where the two countries can actually... Like this could be the place where they really find common cause.

Jiang Lin: I do agree, I think there's a long list in that joint declaration areas both US and China would work together.

Greg Dalton: Albert, just two days before the summit began, China declined to speed up its pledge to reach peak carbon by 2030, and carbon neutrality by 2060, that's a decade later than most other countries, China would say it’s cause they started industrializing later. How much of a shadow did that cast over the whole meeting?

Albert Cheung: For me, not so much of a shadow actually. And perhaps I'm alone in this, but I was not expecting China to come forward with a big new pledge to raise its ambition before COP. It had only really put in place these two commitments to peak emissions before 2030 and reach net zero by 2060. Those commitments are about a year old and I actually would've been quite surprised to see some substantial new commitment there. So, I think I would say that I think overall China's participation in COP was kind of in the end marked by this high point as Jiang has mentioned with the US collaboration. I think that's gonna be the thing to take away from it this is our new kind of flagship achievement that we’re gonna take forward.

Greg Dalton: Right, they didn't really have much of a presence at the meeting, Xi wasn't there, they didn't have an exhibition in the main hall where all the countries are kinda showcasing their presences, but they do have this US, China bilateral deal, and at the end of the day, US and China, about 40% of the missions, top two emitters. They can do a lot. Just those two. Jiang Lin, one of the big critiques of the UN process is that countries announced lofty goals without specific plans or milestones along the way, you've kind of noted, China did recently release its long awaited plan for reaching peak carbon emissions by 2030. That’s not gotten a lot of attention. What does it say? Does that plan provide confidence that China will hit its goal, are we seeing the operational details to say, okay, this is real?

Jiang Lin: Greg, thanks for bringing this up. I think it’s an extremely important development domestically within China. As Albert said, their carbon neutrality goal is only one-year old. So, the entire country is mobilized to plan and draft detailed regulations how this can be done. This is a rather unprecedented effort for still growing emerging economy to put together a carbon neutrality plan in contrast to, well you see countries, that emissions have peaked already and we’re just going down when we go down faster. So, to change the direction of reaching a peaking by 2030, then getting down to zero essentially in 30 years is a pretty tall order I would say. So, everyone as Albert alluded to already are not anticipating a major target revision but rather what are the plans being put in place. So, in China it’s called 1+N plans which, the number 1 is the document issued by the party’s central committee and the state council on the guidance how to reach carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. Which gives a fair amount of detail, including a few more high-level targets for example, including 80% non-fossil energy goal by 2060 that’s lined up with the carbon neutrality pledge. Then the state council issued its own implementation plan on reaching carbon peaking in 10 major areas in different sectors of the economy. So, there’s a lot more details that shed light on how China would go implementing different regulations, policies, incentives to get different sector economy to contribute to the peaking and then reaching carbon neutrality. So, there are a lot more new details in that document.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation taking stock of COP26 in Glasgow. Our podcasts typically contain extra content beyond what’s heard on the radio. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods. Coming up, addressing climate justice through money for loss and damage:

Albert Cheung: Ultimately developing countries hold the rich countries responsible for causing climate change and rightly so for bringing climate change upon them, and we're already seeing the droughts, the storms, the wildfires, all of that affecting the poorest countries, which didn't cause the problem.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about what was and wasn’t accomplished at COP26 in Glasgow with Jiang Lin, adjunct professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and Albert Cheung, head of global analysis at Bloomberg New Energy Finance. During the climate summit, the Washington Post published a big investigation showing that a lot of countries’ claims of carbon reductions are built on faulty numbers. I asked Albert Cheung how troubling this is.

Albert Cheung: Absolutely, absolutely is key, and especially in this decade, in the next few years, between now and 2030, what we need to see delivery on the pledges that have been made. That's really the most important thing. So I think one good thing that's come out of Glasgow is actually some progress on this issue of transparency, where it really comes down to the format of the data that's being submitted by each country and so on and so forth, to make sure that countries are following the same rules and standards and guidelines of how they submit data and progress was made there, some guidelines were laid down there, so I think that will definitely help, but certainly what we need is world leaders to go back to their desks this week and start implementing policies to deliver on the pledges that they've made.

Greg Dalton: The big pledge was the Paris Agreement promised $100 billion a year in financial support for less developed countries, but the full amount of what was promised by 2020 still has not been delivered. It's been somewhere around $80 billion a year rather than $100 billion. Albert, what progress was made on this front?

Albert Cheung: So this may not really seem like progress, but in the final text of the pact, developed countries said that they “noted with regret” the failure to reach the $100 billion mark by 2020. That is meaningful in UN speak. That is an important thing to say, to note that with regret, and it sounds like now the pledges add up to $100 billion by 2023, so we will get there three years late, which is regrettable, but I think that is good progress. Now, I think that it's not gonna be the end of that story, because this whole issue of climate justice is not going away any time soon. So we heard India call for a trillion dollars of climate finance and slightly upping the stakes there, and we've also heard calls for much more of that money to go towards adaptation in particular, so right now there's... I think the total is about $80 billion dollars, I think only a quarter of that goes towards adaptation to help developing countries actually prepare for the very real impacts of climate change, and the UN Secretary General actually said, Antonio Guterres said he would like half of climate finance to go towards adaptation. Now, that wasn't actually agreed, so that's not done, but what was agreed was the pledge to at least double adaptation funding by 2025, so I think that's a really important progress and progress that developing countries would welcome.

Greg Dalton: There is also lots of talk about loss and damage this year, there was a real push by the most affected peoples and areas for additional loss and damage payments, the idea that if rich countries’ actions are damaging poor countries, the ones emitting the most should have to pay for the harm. Albert, loss and damage.

Albert Cheung: It's a hugely contentious issue and again, centered on the question of climate justice, because ultimately developing countries hold the rich countries responsible for causing climate change and rightly so for bringing climate change upon them, and we're already seeing the droughts, the storms, a wildfires, all of that affecting the poorest countries, which didn't cause the problem, so the idea of loss and damage was to set up a fund specifically to pay for the damage caused, and that was not...I don't think that was even close to being agreed in Glasgow, but what the pact does is it acknowledges the issue, recognizes that there is loss and damage being caused, and essentially opens a dialog to explore further how this could be addressed. Now, the issue to me is fairly obvious, is that develops countries, rich countries have zero interest in accepting a liability for something that could run into the trillions because this could be the biggest damages case the world has ever seen, and... So I think this is gonna continue to be contentious for, I think for many cops to come.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, if we admit to it then think of all the legal liability, etc. the corporations, countries, etc. Jiang Lin, your thoughts on kind of this framing, this issue of kind of a moral responsibility really for what, you know, if this happened between individuals or states or counties or corporations right there’d be lawsuits.

Jiang Lin: Yes. I think as mentioned earlier, I think even for a UN document to recognize this clause, the phrasing is it significant enough? It is a very contentious issue; there's no agreement or consensus on it yet. However, it is recognized in text which is a meaningful first step. Just looking back on even the easier question of hundred-billion-dollar funding for developing economy in the Paris since the loss and damage potentials. That's a really important thing to recognize. Developing economies been pushing for this for a long, long time. This was agreed upon at Copenhagen in 2009. So, that’s 11, 12 years going we’re not gonna get there until 2023. So, it is a hugely disappointing outcome for developing economy, pushing for faster action. But also it suggest to me that there is that greater need to be met, this doubling of the adaptation fund is essential progress because for people in Maldives it doesn't matter if you want to build a solar panel on their land or not. They need actually address rising sea level, potentially wiping out their homeland. So, adaptation is a real and urgent need. We see that here in California as well growing wildfires, less rainfalls and drought, etc. So, it is not just somehow, we can fix this problem. We have to start to get used to how do we live with the changing world.

Greg Dalton: Albert, oil prices are the highest in seven years and heading towards $100 a barrel according to some projections, we've seen headlines about potential global energy shortages this winter. Rising energy prices are making politicians nervous about facing angry drivers and voters. Did that strengthen the hand of fossil fuel companies and countries at the conference? Talk about the energy context in which this climate conversation is happening.

Albert Cheung: I actually don't think that the current energy crunch that’s being experienced around the world had such a major bearing in the end on the discussions at COP. Rightly, I think that the focus was much more on the long-term ambitions that we should be setting to reduce emissions. I think that it was right to worry that there might be some sort of backlash to say, Oh, we can't move our fossil fuels so quickly, etcetera. Etcetera. I didn't detect that at all in the discussions, and I think that's correct, because ultimately, my own view is that we're seeing volatility in the market because you have a mismatch between supply and demand of fossil fuels, of liquids and gases that we need to run the economy as it is today, and actually that can happen again and again on the road to Net Zero between now and 2050, that is likely to swing both ways, they'll be oversupply or undersupply at different times, and we're gonna keep seeing these crunches... I think the volatility is just is gonna be a part of the picture and we're all gonna have to get used to it. So in a way, I'm quite glad that we didn't allow that to overshadow this incredibly important conference because these shocks are gonna happen and they're not necessarily linked to the energy transition.

Greg Dalton: Let me turn that around for your Albert and say, what signals do you see coming out of Glasgow that will impact energy and capital markets? You just said that energy markets really didn't affect Glasgow, it was focused on long-term, how does Glasgow affect the energy markets and where money is going and how energy is used?

Albert Cheung: Well, if we wanna talk about money. I think maybe a good place to start is actually the Glasgow Financial Alliance For Net Zero, GFANZ for short, it's a slightly heavy acronym, but this was this agreement set up by Mark Carney and Mike Bloomberg, who’s my ultimate boss actually, between hundreds of financial institutions representing 130 trillion dollars in assets to move towards net zero, and I think that was quite a useful. Quite a useful announcement because it essentially says all of these financial situations. Yeah, they don't have that plans in place right now, many of them are still investing in fossil fuels, but they're setting a direction, and that direction allows us to then hold them accountable, so in the next two, five years we can look back and say, hey, you signed this thing, what have you actually done? In a similar way that we're starting to hold countries accountable for their NDCs, so I do think that is gonna help focus the minds of the finance industry executives on, how do we get capital into clean energy and how do we get it out of fossil, maybe not overnight, but certainly over the next few years.

Greg Dalton: So does that mean we need to wait for governments? Are markets now kind of now moving in a direction that will get to these goals?

Albert Cheung: There's definitely a prevailing sense that business is a head of government at the moment in the whole climate discussion, I'll give you one example. We worked closely with the UK government actually to release a report on zero mission vehicles last Wednesday at Transport Day at COP, and the UK government, the COP26 Presidency put together this declaration of countries and automakers as well as sub-national governments to work towards phase out of polluting vehicles, and we ran the analysis with them on this pledge and essentially found that 20% of the global car market is now covered by national targets to phase out in internal combustion engines, 20%, not enough, but good progress. 30% of the world's car market is covered by automakers’ pledges to phase out internal combustion engines, so that's just one example of where business is moving faster than policies, and I think you'll see other examples in other sectors as well.

Greg Dalton: What about the liability of fossil fuel and big ag and coal companies. It's not all on countries, Exxon knew for decades that they were causing a global harm, Albert, what about the corporate liability?

Albert Cheung: Those are really challenging questions to address, and I may be in a minority among among that, your listeners and all that, but I think that what we really need to do if we want to solve the climate issue is we need to have a big tent and we need to engage with these companies and actually make them do the right thing going forward. I personally am not that interested in the liability of what they've done in the past, it seems like we now know that they hid certain things, we know that they've been lobbying for the wrong side for a long time, but what we need is we need to change policy, we need to change the market rules so that they can't do that anymore, so that they can't invest in the wrong things, and so that they can go on the low-carbon transition along with the rest of us, because I'm not convinced that the courts are gonna be the path to climate safe pathways.

Greg Dalton: And that's been a hang-up in the past, there's been US legislation introduced on a carbon price, but the sort of liability shield for fossil fuel industries was part of it, that was taken out, that's been a real source of contention. Something modeled on what happened with tobacco, we'll give you some money, you can't sue us for what happened in the past. Jiang Lin, let's talk about the global methane pledge that was aimed at reducing emissions of short-lived but potent greenhouse gases by 30% by 2030. How important is this pledge and how much of the low-hanging fruit that just gives political cover for not addressing the thornier issues?

Jiang Lin: I think the global methane pledge is potentially the single most accomplishment during COP26 because we know that methane is a highly potent at trapping heat, potentially 80 times more heat than CO2 traps in the short-term. So if we need a deal with controlling temperature rise in the next decade, reducing methane is the best we have. By some estimates, the pledge of 30% reduction of global methane missions could in itself, shave off 0.2 degrees Celsius in terms of warming by 2040 or so. So that's actually highly significant, and second that most reduction of methane can be done cost effectively, especially in the oil and gas industries, and there's growing consensus, even among stakeholders, industry... That's a missed opportunity in the past. So I think it's highly, highly, significant.

Greg Dalton: Right and that seems to be one area where industry is quite highly aligned, cause methane, there's a lot of basically waste, and to get that to market, you can actually... That's usable energy. Albert, Boris Johnson, who we talked about, chief of the conference, said he wanted to make progress on cars, coal, cash and trees. We talked a little bit about coal. How do you think that played out?

Albert Cheung: On trees, we had this deforestation agreement that was, I forget the number of countries, maybe 100 countries, covering 85% of the world's forest agreeing to stop deforestation by 2030, and that is really quite meaningful. So maybe if you look across all cars, cash and trees, perhaps actually the trees one, is maybe the one with the best new agreement. Of course, it has to be delivered. And actually, we've seen pledges like that made before that we're not delivered, but maybe trees is the one that made the most progress.

Jiang Lin: I totally agree with Albert on the trees topic. I think this is a highly significant because this time there's a real money pledged, nearly 20 billion dollars pledged to preserving forest or stopping deforestation by 2030, so there's a clear end goal there, and by my own calculation, that’s slightly just under 10% of global missions, so that's a big number. And so getting that down by 2030, also meeting our new focus on the next decade, what we can do now instead of the future.

Greg Dalton: This was the first conference of parties or COP with US is back reengaged, US rejoined the Paris Climate Summit. The Biden administration is back after the US has been absent for four years. How credible are US climate efforts when it spends more than a year on defense rather than kind of, you know, on offense talking about Biden's 10-year plan? There was a lot of defense and Biden kind of showed up empty-handed because the US didn't pass by the time he got there the infrastructure bill the Build Back Better Plan. Albert, you wanna take that, US leadership, was it really present?

Albert Cheung: Last time we spoke, last thing I was on the show, I think I said that the US was a bit less credible than I would have liked, but look, the US showed up for COP26. Dozens of political leaders. John Kerry worked incredibly hard for the two weeks that he was there the whole time, and I think it did show that the US is back, that it wants to engage and it wants to lead and like many other countries, the US showed up having already made the pledges really, there were not that many new pledges made at Glasgow, so the US had already set forth its plans to reduce emissions by 50% or more than 50 cent by 2030. And etcetera, etcetera. So it wasn't like Biden was completely empty-handed. He did deliver on at least the infrastructure bill during COP 26 that is now done, but not yet on the economic spending bill, which we really have been a big boost to clean energy, so I would give the US a qualified maybe three or four stars out of five for what they did on the day in COP given the constraints that the administration faces back home. You know the US wasn't able to sign the coal declaration, wasn't able to sign the electric vehicles declaration, because those are not realistic political prospects to get agreed back home.

Greg Dalton: Right, and I wanna ask you how change happens, because looking at climate Twitter during the conference, there were a lot of people, young people, particularly who were really disappointed, angry, said we need to talk about revolution, they really need to shake up the system because they think the establishment is not going to deliver the reductions needed, and that there's gonna be more political pressure. We saw some of this during the conference of parties, Greta saying this is all blah, blah, blah, some youth walking out, etcetera. So Albert, having been there, your sense of like, is the establishment, the elites gonna get this job done, or is there gonna be more civil disobedience as the world gets hotter? Desperate people take more desperate measures?

Albert Cheung: I don't think we are on track for 1.5 degrees, so I think it's right that people are angry about that. And you're gonna have the campaigners and the activists and the NGOS who essentially pan the Glasgow pact and say, it's green wash, it's just blah, blah, blah. It's just words. But you have to remember, words are all the negotiators have in that conference room, what you're trying to do is get 200 countries to agree on a text, and the text is the path forward. They're not in there planting trees, they're in their crafting words, and you know what those words say, if you read it is, let's come back next year and keep trying harder. So I think it's good to be angry, I think that anger helps, but I think to say that these people aren't trying or aren’t doing enough, I think they're working hard, and I think this is the right system and the right process to try and get to a better outcome.

Jiang Lin: I think the young people are right to be disappointed, to be frustrated, I think bring the pressure on, and that's what's gonna get going... It's a democracy, we need our citizens to be engaged, to push for what we hope for, so don't let the pressure drop, but also broadly speaking, I think the UN is only one avenue of change. It's an important one, but it's only one, it takes some model sources of change to make it happen, including every day activities each citizen can take on, but also in your own local jurisdictions, industries as well. So I think that we need to start mobilizing different sectors of society to all work on this common goal, just hoping for one UN document to solve our problem is probably not realistic and cannot be counted on.

Greg Dalton: That was Jiang Lin, an adjunct professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and Albert Cheung, head of global analysis at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, weighing in on what did and didn’t get accomplished at COP26. This is Climate One. Coming up, African climate activist Vanessa Nakate says we will only be able to have climate justice if everyone is involved:

Vanessa Nakate: I know and believe that every activist has a story to tell and every story has a solution to give and every solution has a life to change.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Vanessa Nakate is a Ugandan climate justice activist. Inspired by Greta Thunberg, Vanessa began a solitary strike for bolder climate action in 2019. Vanessa founded the Youth for Future Africa and the Africa-based Rise Up Movement. Her advocacy recently landed her on the cover of Time magazine. She begins her new book A Bigger Picture (My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis), with the story of a press conference at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

Vanessa Nakate: In January 2020, I got an invitation from the Arctic base camp and it was to go to Davos and at the same time the World Economic Forum was happening. And I remember getting in Davos and my very first experience of Davos was how extremely cold it was and how my hands really hurt because I didn’t have any gloves on. And then I got this invitation to speak at a press conference with other activists from Europe. And I was just so happy about this invitation and excited because I've been at a press conference before and they always have quite a number of journalists and it’s always a good place or an opportunity or a platform to really talk about the experiences of very many people, especially with the climate crisis. And I remember one of the things that I really emphasized at the press conference was the importance of listening to every activist from every part of the world. So, later on I see a picture and then an article and I realized that my name is not in the article and my face is not in the picture because it had been cropped out. At that moment when I saw that I just wanted to ask why I had been cropped out because I knew that I had been cropped out. And when I asked why there’s just a lot of support that really came in from different people from different parts of the world. And to me it was a representation of the continuous erasure of activists who are on the front lines of the climate crisis.

Greg Dalton: And you were the only person of color, the only black person in the photograph?

Vanessa Nakate: Yes, I was.

Greg Dalton: And how did you cycle through your feelings from being hurt on an individual level, anger, what did you feel like when you realize you were cropped out?

Vanessa Nakate: Frustrated. Heartbroken and really hurt. And also disappointed because like I’ve said, one of the things that I really emphasized was the importance of listening to every activist and you know how we will be able to have climate justice only if everyone is involved. I know and believe that every activist has a story to tell and every story has a solution to give and every solution has a life to change. So, when I saw these it was very hurtful, a very hurtful experience and it’s something that you know when someone asks me about it it's still a place that takes me back to those experiences.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I worked at the AP and I'm embarrassed that the AP was an organization that cropped you out. You tweeted to the AP you didn’t just erase a photo you erased a continent. Quite powerful. In his analysis of the photo, Dr. Robert Bullard who’s known as the father of environmental justice in the United States said that, “Climate activism among youth is perceived by larger society today as a ‘white thing’. The un-cropped photo didn't fit this model." How do we get that model to change?

Vanessa Nakate: Well, I think it really starts from people understanding the urgency of the climate crisis and people understanding that, you know, communities of people at the front lines of climate change did not cause the climate crisis. For example, historically, Africa is responsible for only 3% of global emissions and yet Africans are already suffering some of the most brutal impacts fueled by the climate crisis. We’ve seen the occurrence of droughts, the occurrence of floods, the occurrence of landslides, cyclones in different parts of Africa, locust invasions. And these have really affected the access to water for many communities. Availability of food for many communities. Education of many children and the hopes and dreams and futures of so many children being destroyed as these disasters escalate. So, people need to understand that while Africa is on the front lines of the climate crisis it’s not in the front pages of the world’s newspapers. And I think the only way that, you know, we can change these it’s simply by listening to the activists who are speaking up platforming their voices and amplifying their voices. People also need to know that we may be facing the same storm but we are definitely in different boats. So, as some people in way stronger boats other people are in more weaker boats some people’s boats are already sinking and have already lost everything. Some people’s boats are heading to that same direction of destruction. When people understand that that is, you know, the horrible reality of the climate crisis that those on the front lines, those who find themselves in much weaker boats did not cause the climate crisis, then it would be easier for people to pay attention to what the activists from Africa or the Global South in general are talking about when they are demanding for climate justice.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, it’s deeply unjust that the people who caused it least are feeling it first and worst. You've organized climate strikes in Kampala, the capital of Uganda where you grew up and as well as trying to get your voice heard at international summits like Davos and Glasgow. How is your message different when you're speaking in Africa or in Europe?

Vanessa Nakate: Yeah, when it comes to the people in Uganda, especially the schools that we go to to do like education about climate issues. This is mostly about creating awareness and you know awakening people to their connection to nature. Many people don't know about the realities of climate change. However, people do see the floods, people do see the droughts because some of these things are talked about on the news when they happen. People see the occurrence of landslides. So, I think that's you know for people who aren’t on the front lines the most important thing to do is to give as much education as possible to communicate the crisis and create as much awareness as possible because the more people know the more people will want to come together and work together and demand for climate justice. But when I come to Europe, I'm not here to create awareness of climate issues because the corporations know that their actions are harming the planet, leaders know that when they take specific decisions, they’re going to hurt the planet. So, it’s a place of saying your actions the more you're funding the digging up of fossil fuels in your country in our countries the more people are losing their farms. The more people are losing their homes. The more people are losing their businesses because of your continuous actions, because of your continuous environmental destruction, many people’s livelihoods are being destroyed because what happens in Europe doesn’t end in Europe.

Greg Dalton: Just prior to COP 26 you gave a keynote speech at the Youth for Climate event in Milan. I’d like to play a bit of that speech.

[Start Playback]

Vanessa Nakate: For many of us reducing and avoiding is no longer enough. You cannot adapt to lost cultures. You cannot adapt to lost traditions. You cannot adapt to lost history. You cannot adapt to starvation. It’s time for our leaders to stop talking and start acting. It’s time to count the real costs and it’s time for the polluters to pay. It’s time to keep their promises. No more empty promises. No more empty summits. No more empty conferences. It’s time to show us the money, it’s time, it’s time, it’s time. And don’t forget to listen to the most affected people and areas. Thank you.

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: That was quite a powerful moment there. Who do you think most needs to hear your message and is it breaking through to people in power?

Vanessa Nakate: The people who really need to listen to my message and to my demands I think it is really the people in power. The people who are continuing to construct oil pipelines, who are continuing to frack gas, who are continuing to open coal power plants while promising us net zero by 2040 by 2050 or by 2030. They are the people who really need to listen, you know, to my message. But not just my message, the message that has been spoken by a number of activists in this generation. Activists who have been there, you know, way before we started activism. That is the message that we want the leaders to listen to and to give action, to give justice. Justice that has people at its center. We want the climate justice to have people at the center of the decisions of the leaders. And of course, one of the things that I really emphasized in that speech was loss and damage. Leaders must understand that loss and damage is here with us right now. They have to acknowledge that they have to put loss and damage on their agenda and they have to give the money for communities that are already experiencing lost and damage. And this money, we want it in grants and not in form of loans.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, that very simple concept, if someone's pollution or water sewage runs onto their neighbor's property they would be expected to pay and clean it up and that's what's happening on a global scale and the people who are responsible are not paying for that. Recently Royal Dutch Shell CEO Ben Van Beurden spoke at a conference before Glasgow and activist Lauren MacDonald got up and really shouted at him in a way that gained a lot of attention.

Greg Dalton: Let’s hear that clip now:

[Start Playback]

Lauren McDonald: If you’re going to sit here and say you care about climate action, why are you currently appealing the recent court ruling that Shell must decrease its emissions by 45% by 2030. I seriously don’t understand what goes on in your mind to sit there and say ‘I’m trying to do better when you’re not doing it. (applause) Being legally binded to climate action. So yeah, my question, it’s a yes or no question, will you repeal this, if you care, will you repeal this?

Ben Van Beurden: Repeal the appeal, you mean?

Lauren McDonald: Yes.

Ben Van Beurden: Well, you gave some context--

Lauren McDonald: I’m going to take that as a no. I hope that you know that we will never forget what you have done and what Shell has done. I hope you know that as the climate crisis gets more and more deadly, you will be to blame. And I will not be sharing this podium with you anymore.

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: I'm curious what you thought about that moment where a youth activist really was on stage on the TED stage with the Shell CEO and really spoke quite directly and unexpectedly and forcefully to him.

Vanessa Nakate: I think it's really powerful and inspiring when youth activists do that and they speak truth to power in front of leaders in front of presidents or vice presidents or corporations like Shell. And I also think that it really tells a lot when you know people are destroying the environment, people who are destroying the planet, you know are the same people who are given spaces to discuss our future. You know, it's kind of you know, contradictory the same person who is fueling the climate crisis to be invited to talk about climate the future of climate solutions and all that. So, I think that it's really powerful when youth activists speak truth to power and demand for accountability when leaders or when oil giants are given spaces that they are not supposed to be given to.

Greg Dalton: How did you learn about climate change first in boarding school and then on your own?

Vanessa Nakate: In boarding school climate change is usually one of the topics in geography class. And I remember learning about it as every student because when you ask any student either in primary school or in secondary school what climate change is they will tell you this is, you know, the average change in weather conditions over a long period of time. But no one will tell you that climate change means drought, means floods. The time I got to start to understand the urgency of the climate crisis, it was in 2018 towards the end of 2018. And it was through my own personal reading and realizing how urgent of a problem it was and how it was more than, you know, that definition that we all knew, that definition that every student knows that it was something that was impacting the lives of the people right now. Something that was, you know, threatening the livelihoods of very many communities right now and it’s really in that period that I decided I would do something about, you know, the climate crisis. And after being inspired by the climate strikes, which were started by Greta, I decided that it would really be a very powerful way to demand for climate justice and also create awareness.

Greg Dalton: I get chills hearing you talk about that. You’re the eldest of five kids growing up in Kampala. Share the moment when you told your mom you were going to a climate strike. Take us to that moment.

Vanessa Nakate: Yeah, it was actually a Saturday. My very first climate strike was on a Sunday because I took time before starting the climate strikes, as I was really scared to go to the streets. And the time when I felt like you know that feeling of you know you've taken so much time and that feeling of urgency that a lot of time has been wasted. And then I decided to say to myself that I'm going to do this climate strike. And I realized that it's Saturday and Friday is gone and then like no I can still study on a Sunday and then catch up with everyone else every Friday. So, Saturday I told my siblings and cousins about it and they are really excited. And when we are making the signs, you know, that’s when my mom comes and asked us what we are doing. And we tell her that we were writing, you know, on the climate signs and we were going to do a climate strike. She didn’t understand what I meant by the climate strike when I told her. But then I explained what it really meant and she was kind of, you know, worried and feeling nervous about us going to the street. But then I told her that we would be safe and she wouldn’t have to worry about that. So, we went for the climate strike and we did the strike in four different locations because again like I felt that urgency that I should have spoken up way earlier. So, I just wanted that we do this in like as many locations as possible that we can reach so that we can create lots of awareness about the climate issues in just one day.

Greg Dalton: And then your sister Claire said you were brave and Greta retweeted your photos and you’re often on your way. But being a young female activist is more dangerous in Uganda than in Sweden. You also had to overcome sexism in your bringing at the boarding school you attended. So, how are you taught that young women were supposed to behave and how do you still need to counter Ugandan gendered ideas?

Vanessa Nakate: Well,by the time when I started the climate strikes, I was just about to graduate. And it’s like society has a specific plan on you know what on how your life should be especially after school. I remember my graduation party that was organized by my parents there was some speeches, especially from relatives you know saying that you know thank you for this big celebration and we can't wait for the next celebration, and that was my wedding. So, there is always that pressure on your graduation, I think every girls feels it the pressure on your graduation party that there is a demand that everyone can’t wait to celebrate when you get married or something, you know, like I remember my dad saying that I think my parents spoke last. I remember my dad saying that you don’t have to feel like you’re in a rush. Yeah, that’s what he told me and he said, you can do whatever, whenever you want.

Greg Dalton: How wonderful.

Vanessa Nakate: Yeah, dad is really cool.

Greg Dalton: He sounds really special, yeah. In Uganda families have to pay for their kids to go to school. The idea of skipping school for a climate strike could be seen as betrayal of the whole family, was that ever an issue?

Vanessa Nakate: Right. Well, the time when I started the climate strikes, I wasn't going to school anymore because I was just waiting for my graduation. This is something that, you know, I’m trying to find words how to explain it but it’s something that many students would face in Uganda because there is that's you know feeling of you know growing up being told education is the key to success and knowing that you have to finish school and also knowing how much hard work your parents really put in in assuring that you stay in school and all that. So, students have like this respect for their parents and also for the opportunity to be in school. So, it's not that they will easily walk out of school and also, they could face the school is gonna have like security personnel so you can’t just you know walk out you could be suspended if you forcefully do it or you could even be expelled. And in many cases your parents may not get a refund of some of the money that they have already spent. And also, many students are in boarding school so again, it’s really impossible for students to walk out of school, usually boarding school. You get out maybe when you’re going back home for holidays or when you’re going for a school trip. And then the other thing is the issue of access to phones. Usually, students many children get phones at 16, 17 and sometimes 18. So, it’s hard to keep like that kind of coordination through the phone or through the internet as well.

Greg Dalton: Well, I just have such respect for all the risks that young girls take the social expectations of what girls are supposed to do or not do. The economic pressures the expectations of the family’s future taking a lot of risks when they engage in those climate strikes. You point to education of girls not only as an equity issue, but also a climate issue. How do those relate because they’re not often seen as connected?

Vanessa Nakate: Yeah, it's something that I also started to learn. In my activism I've just been learning and learning and learning and trying to educate myself as well. So, I learned that Project Drawdown lists 100 things that we can do to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and ranked number five is education of girls and family planning. So, Project Drawdown say that when more girls, you know, educated and more women are empowered this could be a very powerful solution that could help us tackle the climate crisis. One, this is a solution that would help reduce already existing inequalities that women and girls face in society. This is a solution that would help build resilience of you know many women and girls in the society. And this resilience is not something that only benefits the individual it extends to the family. It extends to the community. It extends to the world at large literally when more girls are educated when more women empowered. It gives all of us a lifeline and it's also a solution that is going to reduce greenhouse gas emissions all at the same time. So, when I learned that I thought it would be really powerful for people to learn that you know education of girls and women empowerment is a powerful tool to addressing the climate crisis.

Greg Dalton: Greta has said that boomers, people in power often say to youth, oh, you know, you give me hope you’re going to inspire us, you’re gonna solve it. And she pushes it right back on them and says, don’t give me that. It’s the patronizing, you know, you’re in power you solve it. So, I’m curious if when you’ve encountered these people in power in Europe and the Global North if you felt that similar sense of kind of, I don’t know patronizing towards you and they acknowledge you as a cute kid but they don’t really, yeah, that it stops there. Have you had that experience?

Vanessa Nakate: Yeah, I’ve had that experience of, you know, being called inspiring and being told that young people are going to change the world. And this just really ends there but they never really take action from the demands that we are asking for. And well, a few weeks I made like a TikTok and it was basically saying how some of the leaders praise young people but then they continue, let me say with the extraction of oil. So, it was more of young people are inspiring but we love our oil, don’t touch it. And young people are going to change the world as long as you don't talk about our natural gas. So, basically it was I think that many people are relating with many activists that leaders are always there, you know, to praise and call young people inspiring and take pictures with them. But then they never do what the young people are asking for.

Greg Dalton: How do you deal with setbacks? Those feelings that no one is listening, the change that you want isn’t happening, that kids, youth might be used as props. What’s your advice to others who feel the same?

Vanessa Nakate: There’s a time when I felt like the inaction of the leaders was beginning to frustrate and depress me. And I just felt like we continued to strike, disasters continued to happen but then the leaders continued to act like nothing was happening. So, in that point I was really depressed and I stopped striking and I just couldn't get the strength to go to the streets because I was just so frustrated about the inaction of the leaders. But now when I was able to get through that situation I just chose to really have hope and I know that in many spaces you know where I may meet leaders I’m going to expect, you know, those kinds of words of inspiring and, you know, calling me inspiring or saying I’m going to change the world. I think that when those times come, I just really want to say, no, you are the ones to change the world. You are the ones to make decisions that will make this planet a better place. Because it’s more like when the more you keep saying young people inspiring, you’re carrying all your responsibilities and giving it to us. So, I just feel like when that happens, I just want to take back the responsibility to the leaders and say, yes, I am an activist and this is what I’m asking for. I’m not asking for praises; I’m not asking for pictures. I’m asking for justice.

Greg Dalton: Vanessa Nakate is a Ugandan climate justice activist and author of A Bigger Picture: My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis. Thank you, Vanessa, for coming on Climate One.

Vanessa Nakate: Thank you for doing this interview. I appreciate it.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One... We’ve been taking stock of what happened at this year’s international climate summit, COP26. Support for today’s program was provided in part by The Erol Foundation. Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe to our podcast on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation. Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Ariana Brocious is our producer and audio editor. Our audio engineer is Arnav Gupta. Our team also includes Steve Fox, Kelli Pennington, and Tyler Reed. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.