Fairytales and Fear: Stories of Our Future

Guests

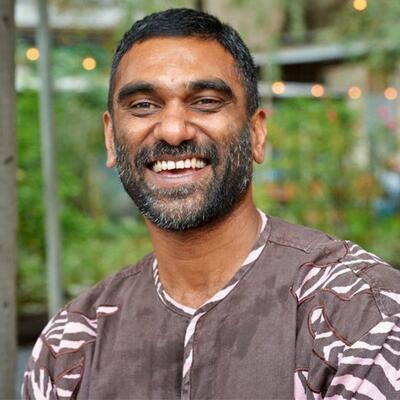

Denise Baden

Paolo Bacigalupi

Tory Stephens

Summary

Stories are the way we remember, the way we share knowledge, the way we play out possible outcomes. Climate fiction imagines dark or bright futures depending on how we address the climate crisis. But there’s a healthy debate about what kind of writing inspires more people to act.

Fiction writers like Paolo Bacigalupi tend to frame our climate future as dark and dystopian as a way of pushing people to pay attention and take action.

“A well-written story of warning can create a sense of unease and a sense of awareness that otherwise doesn't exist for people,” he says. “I think that if you want to create change in a democratic society, people have to believe that there is actually a threat.”

His 2015 dystopian thriller "The Water Knife," set in a water-starved Southwest, features a central character known as a "water knife" — sort of an assassin/spy who sabotages and steals water from neighboring states. Bacigalupi says he was driven to write this story after witnessing the historic drought in Texas in 2011.

“It was terrifying,” he says. “They were in an ahistorical experience, and yet it also matches very closely with what climate scientists predict for our future. And so in that moment when you're there looking at this disaster unfolding, you can think, ‘Oh, I'm in a drought.’ Or you can say, ‘Oh, I'm time traveling. What does this future look like?’”

He wants readers to feel disturbed by the close parallels between his writing and our present reality – and be driven to take action.

"I hope to make them feel like the walls of their home are closing in on them. That nothing that they live in is stable or secure. I hope that they are horrified and think, 'Oh, just because today looks good doesn't mean tomorrow is safe,'" he says.

Despite the widespread popularity of climate dystopia in literature as well as on TV and in Hollywood, writers like Denise Baden think that’s the wrong approach to take. In addition to her work as a sustainability professor in the U.K., she writes climate fiction and leads climate fiction contests called Green Stories. She also edited a recent anthology of hopeful climate stories called “No More Fairy Tales: Stories to Save Our Planet.”

“Positive stories with solutions, whether it be in the field of news or education or fiction, actually engage way more people than more catastrophic tales of what will go wrong if we don't do anything,” she says.

Hope is also a driving factor behind the climate fiction contest organized by Grist, a nonprofit online news outlet. Climate Fiction Creative Manager Tory Stephens says they wanted to encourage the creation of climate stories that are inclusive and resonant for all people. Their “Imagine 2200” contest brief asks writers to submit intersectional and hopeful stories of the future.

“The genre is changing, but many of the [climate fiction] stories I read did not have frontline community members,” Stephens says. “So I really wanted those folks to be represented. We wanna see everyone reflected in this fight for a better climate.”

This episode features an excerpt of the audio recording of “The Cloud Weaver’s Song,” written by Saul Tanpepper and recorded by Curio.

Episode Highlights

3:30 Paolo Bacigalupi on the climate realities behind "The Water Knife"

9:30 World-building for a more humane, equitable future in fiction

13:00 Future tech versus today’s technologies

18:00 Writing as catharsis for climate anxiety

20:00 Whether fear or hope is more effective in driving action

26:30 Denise Baden on power of storytelling to reach people more than data

28:33 Dystopian stories are like “revving an engine without being in gear”

30:45 Concept of "through-topia"

39:00 Excerpt of "The Cloud Weaver’s Song" short story

45:45 Tory Stephens on why intersectional climate fiction is essential

49:00 How storytelling can reach many people beyond "news junkies"

Resources From This Episode (4)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One, I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious. Today, we’re talking about climate fiction. And I’m excited to dig into it.

Greg Dalton: As we talked about in our episode a few months back with television producers, climate is a growing topic in Hollywood and on TV. But there seem to be more works of literature that delve into the consequences of burning fossil fuels.

Ariana Brocious: And as we know, stories are probably the most compelling and effective way we have of sharing and remembering information – our brains are hardwired for it. But there’s a healthy debate about what kind of writing most inspires people to act.

Greg Dalton: Right, and what sells as entertainment and what causes people to act may not be the same stories. Fiction writers like Paolo Bacigalupi have a tendency to frame our climate future as dark and dystopian as a way of pushing people to pay attention and take action.

Paolo Bacigalupi: A well-written story of warning can create a sense of unease and a sense of awareness that otherwise doesn't exist for people.

Greg Dalton: Despite the popularity of climate dystopia, writers like Denise Baden think that’s the wrong approach to take.

Denise Baden: Positive stories with solutions, whether it be in the field of news or education or fiction, actually engage way more people than more catastrophic tales of what will go wrong if we don't do anything.

Ariana Brocious: And some, like Tory Stephens, are focused on ensuring climate stories are inclusive and resonant for all people.

Tory Stephens: So many people are story driven. So we wanna reach all people around the climate crisis and talk about climate solutions, the hope and justice side of things.

Greg Dalton: Let’s get into your conversation with Paolo Bacigalupi, an award-winning bestselling author of speculative fiction.

Ariana Brocious: In 2015, you published the water knife, a dystopian thriller about a water starved southwest in which the poor eke out a dusty survival while the rich enjoy lush elite reserves. And in Nevada, a central character known as a water knife, which is sort of an assassin slash spy. Sabotages and steals water from neighboring states. In this world, the Western U.S. has devolved into a militarized landscape where every state has its own border patrol to keep water crisis refugees from states like Arizona and Texas out. The picture you paint in this novel is pretty dark, I would say. And it also, as a resident of the Southwest, feels possible. So I'm wondering, what drove you to sort of create this grim future?

Paolo Bacigalupi: I think that, I mean, the reason why I ended up writing this book, specifically, The Water Knife, was because I wanted to talk about climate change, and I wanted to set it in a space that felt viscerally vulnerable. And, and it was specifically because I felt like I was watching a lot of trendlines that were all going in sort of the wrong direction. The moment when I decided I was really going to be writing about drought and about climate change, and specifically in the United States happened because I was actually down in Texas during their major drought in 2011. And it was a terrible drought. you know, their farms were sort of going dry. They were having to kill off their cattle. There were rolling brownouts because their hydroelectric dams didn't have enough water in them to have enough hydraulic head to spin their turbines.

You were seeing record breaking numbers of a hundred degree days, and this is back. You know, look, my gosh, this is like 13 years ago now, and it was this, it was, it was terrifying. It was this moment where, you know, they were in an ahistorical experience, and yet it also matches very closely with what climate scientists predict for our future. And so in that moment when you're there looking at this disaster unfolding, you can think, oh, I'm in a drought. Or you can say, oh, I'm time traveling. You know, what does this future look like? And, and that, that was sort of the beginning point. And that was combined specifically with the fact that Rick Perry, the governor of Texas at that time his response to that massive drought was to go around and, and urge people to pray for rain. And so there was this sort of magical thinking sort of attitude towards what would resolve these problems and how we would become resilient to these problems. Let's pray. As opposed to, wow, these things are real serious and they're going to get worse. And we need to actually start building, you know, a policy future and an infrastructure future that's more resilient for what's coming. The reason why I wrote in this Colorado River and the Southwest is because I grew up in the Southwest and so I've always been aware of water and drought issues. And there's a lot of climate data that says that this is a vulnerable area. So it was a good space to sort of set the story in and try to sort of open up some of the questions and uncertainties that exist around climate change.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, and I mean, in the moment we're in, we have reached a really scary point on the supply of the Colorado River this year. And states like Arizona are already taking pretty significant cuts. And you know, the discussion continues around trying to find collaborative ways of working together to sort of share the water, share the less water. So we're not yet at a point that is obviously as dark as we get to in the Water knife, but we can also see that future. And I'm wondering do you think some of your writing, some of the dystopian elements of the writing are predictive of what could happen or are they rather sort of cautionary tales that we should try to avoid?

Paolo Bacigalupi: I think I'm writing the stupid version of a human future. It's the one where people make all the dumb decisions, the selfish decisions, the ignorant decisions, and then you sort of extrapolate from there. So if everybody lives in denial about whether or not we're gonna have lots of water in the Colorado River, We're gonna eventually have a bunch of subdivisions that have to be dried up because we just don't have the supply. Or, you know, there's gonna be cuts somewhere. Somebody's gonna hurt, somebody's gonna take that. Whether that's at a, you know, state versus state level or whether that's a subdivision versus subdivision level. And something like The Water Knife just goes on the assumption, and really it sort of is balancing these two concepts: One of them is, you know, that Las Vegas recognizes that it's incredibly vulnerable and starts making moves to try to protect itself. And Phoenix sort of tries to pretend like nothing's wrong and as a result starts to collapse. I think that one of the things that's interesting to me about our present moment with the Colorado River is that everything that's happening now was pretty damn obvious, you know, 15 years ago. This was not some like, “Surprise. Oh my goodness. We ran outta water!” This was like, we are running out of water. This is happening. Get on the program and instead we pretended for the last 15 years we could have been building resiliency for 15 years. and instead we've done nothing. And now, you know, like now it's come together with a collaborative solution. Oh. And you know, and then everybody dickers some more while they try to figure out like, how bad is this drought this year? As opposed to how bad is the long term prognosis for us.

Ariana Brocious: There's one line, from a character in the water knife early on that really exemplifies this and I'll just read it.

“We knew it was all going to hell and we just stood by and watched it happen. Anyway, there ought to be a prize for that kind of stupidity.” And just to sort of underscore what you, you just said, I think that's a great, and he's speaking about the water crisis, you could equally apply that to the climate crisis.

Paolo Bacigalupi: Right? Yeah. I mean, I feel like that's the kind of the central argument of the entire book is that question of, do we engage with reality seriously, or do we try to pretend that reality isn't coming at us? And, and so far, I mean, it's weird, like the jury's still out on that. I'm somewhat regretful that, that The Water Knife feels more predictive now than it did when I was writing in 2014 about I remember when it came out in 2015, the United States had just joined the Paris Accords, and I thought, oh, well maybe we're actually heading towards a more rational future in some way. And then right after that we elected Trump and I thought, oh, well, no, we're actually headed for more stupid.

Ariana Brocious: So I wanna turn now to a short story that you contributed to this anthology called No More Fairy Tales and elsewhere in this episode, we speak with the editor of that anthology. So in this story, in a future Chicago redesigned lower income neighborhoods rely on solar power microgrids. People get around using autonomous on demand public transport called Hood Zips. So if you would, I'd like you to read one excerpt that helps set the scene.

Paolo Bacigalupi: James was just old enough that he could remember when streets had been for cars. Now more than half his neighborhood street was dominated by solar panels and home gardens with only a thin lane for the hood zips to navigate through. In summer, the reclaimed street was full of vegetables and flowers and buzzing bees and people sitting on benches beneath the shade of high mounted solar panels.

Ariana Brocious: So to me, that sounds kind of idyllic, and it also touches on these aspects of resilience, urban planning, food and energy supplies, public health, community. So when you're thinking about world building or designing, you know, the setting for a story, what do you think about when it's rooted in sort of a climate fiction or climate driven narrative?

Paolo Bacigalupi: So when I was writing that particular story, I was trying to imagine a world that seemed fairly equitable, humane and I think when I was trying to create that world, I was trying to describe one where there was space for human beings and the natural world to exist in some sort of integrated whole, where it wasn't simply the monoculture of sort of human concrete space, nor was it necessarily the idealized wildness of the far distant wilderness, but that there could be some sort of an integrated and mutually supporting sort of landscape and that that would encompass, you know, whether that was gardens or whether that was animals, or whether that was people, whether that was social lives, whether that was, the shelter that we need.

For, for our own comfort, but also the, the spaces to be social and connected with one another. And, you know, recognizing that human beings also thrive best when we're in contact with the natural world. I was trying to sort of bind all of that together with the idea of like, you know, where do, how do you create, energy generation patterns that make that possible and better as opposed to sort of feeling like, your coal power plant basically makes it impossible for anybody to live next to it.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, and it's a nice world and the story has tension, But I'm wondering when you're thinking of writing a story, how much does the central driving plot affect whether the world that the character is in is a more dystopian one or more utopian? Is it because they're reacting to the stimulus of their world or that they're, you know…

Paolo Bacigalupi: Right. So the way that I think about this is I think about there's, there's kinds of stories that you wanna write and some of their more warning stories. That's something like The Water Knife where I'm trying to give people a sense of unease about their future. And those warning stories, you're aiming to create an echo against their present world, that'll make them feel very uneasy. So you'll have an example like Lake Mead getting lower and lower and lower. And then in the future, what does that look like? And then, you know, when they read a news story today about Lake Mead getting lower and lower and lower, they suddenly are very unnerved. And that's, that's, you know, one version, in this, you know, sort of more inspirational line, you're trying to create a similar set of echoes. Almost always the goal is to make the background either create the enticement or the unease. That should be the background setting of the world. It's easier if the characters then just live in that background setting and conduct their human lives against that background setting, rather than them being set up as either good guys or bad guys advocating for values. That allows you a lot of freedom to tell stories without having to be sort of locked into sort of a value set fiction sort of framework.

Ariana Brocious: So in this story, in this kind of future world, renewable energy on the main grid is managed and stored via a set of weights and pulley on the sides of skyscrapers managed by artificial intelligence named Lucy. This story centers around a father and a son, and this split between a kind of hard fought, locally generated solar power and this large utility that generates power also renewably. That is a tension that exists today in our world. So tell me about the choice to include that, where it's very easy to sort of understand that the reader can get it doesn't have to imagine, uh, versus trying to incorporate maybe a, a different, more futuristic kind of technology.

Paolo Bacigalupi: One of the things that I've been really fascinated about for years, is William Gibson's quote that the future is here. It's just not very evenly distributed. And a lot of what I think of science fiction is an argument about which future is already here, just not quite evenly distributed. And so, we have big utility scale grids. We have the back to the lander type who wants to just have their little solar panel and their battery and like live off grid. You know, all of these things are in existence already and one of the things that I think is really interesting right now specifically, and partly because I'm part of a local electric co-op that's been fighting against a larger utility and had been fighting for more independence is, you know, who benefits from power generation, where that power generation comes from, what choices of the energy mix that go into that power generation. So I wanted to incorporate some of those ideas, both the insurgent power of these small technologies that are becoming more and more democratized. But also I wanted to talk about, you know, in order to make landscape level global impacts, we need big, large organizations to be organized well and skillfully. If we rely entirely on the micro consumer doing their part recycling, adding their solar panels and stuff like that. We aren't gonna get where we need to go. We need to have policies and organizations at a much, much larger scale getting on board and moving in certain directions. And the nice thing about that is that then you can do really extraordinary things. And that was one of the things I wanted to showcase in “Efficiency,” was this idea that, oh yeah, if you have a utility level storage solution, you could do something amazing. You could have all of these giant weights moving up and down the sides of buildings and have them be lit up as light displays and, and they can be storing energy, but they can also be like a visually sort of exciting thing.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. And I was really excited by this possibility of gravitricity, I think is what is what it's called, which was something I learned about reading your story I didn't actually know was a possibility. So this story is in an anthology that's focused on driving better understanding of real world climate solutions. So given that it's part of that anthology, I could imagine you feel some responsibility to help do some of that education. But speaking more broadly, is that something you feel a responsibility for? Actually helping educate readers? Or is that sort of a side thing that happens along with entertaining?

Paolo Bacigalupi: I'm a fiction writer first. I feel like my first duty always is to entertain. If I haven't sucked my reader in, if I haven't given them an interesting world to live in. If I haven't given them interesting characters to care about, all of the rest of it doesn't really matter. So entertainment first always. Then there's a question of like, are there values or ideas that I want to sort of spin out or introduce? And that's gonna depend. A lot of times it's just gonna depend on, at the short story level, it's a really different thing because oftentimes those are these very clear thought experiments where you drop an idea bomb in and you see if it explodes kind of, and so you have a lot of flexibility to sort of, get in, hit something and then jump back out. And, and I've done that with something like “Efficiency,” where you're trying to create an inspirational future. And I did another short story a while ago, which was essentially a small story about a young girl moving around and her family continually being blasted out by climate change impacts, whether that was, you know, electricity generation problems or, or hurricanes, or whether it was a financial collapse. And it kept her family moving and being chased by disasters basically. And those stories definitely, you're sort of like trying to leave people with, you know, some kind of a message. You're trying to leave people with some kind of an idea about the future. And for a while when I was writing fiction, I felt like I needed to sort of justify sort of the bourgeois luxury of just making stories up by also making them meaningful that it wasn't enough to tell an entertaining story, but it also had to carry some other larger value, weight, or idea weight. And if I wasn't doing that, then I wasn't necessarily being a good contributing member to my society in some way that I was simply being, you know, sort of a lazy, selfish jerk. I don't really believe that now. My, my world has changed. My life has changed some. and honestly like spending so much time in the, the sort of the climate change world, sort of tracking what's happening, writing stories about it, being immersed in the what ifs of it. That eventually became exhausting and overwhelming, and so I've pulled back a lot from that.

Ariana Brocious: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation with author Paolo Bacigalupi. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods.

Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. On our new website you can create and share playlists focused on topics including food, energy, EVs, activism.

Coming up, why Paolo Bacigalupi wants his readers to feel scared about the world he’s creating:

Paolo Bacigalupi: I think that if you want to create change in a democratic society, people have to believe that there is actually a threat.

Ariana Brocious: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

This is Climate One. Let’s get back to my conversation with speculative fiction author Paolo Bacigalupi. Reading climate news or reports day in and day out can be anxiety-provoking and emotionally draining. I asked Paolo if writing about climate is cathartic in and of itself, in helping him process the moment we’re in.

Paolo Bacigalupi: There's definitely a cathartic sort of feeling of like, oh, here's an anxiety I have. Okay, I placed it on the page. Now it's over there. It's not living inside me anymore. There was definitely a strong pattern of that where, oh yeah, I'm watching. the irrigation canal behind our house is shut off early. Okay, now I'm stressed out again. It's like, okay, now I can put that fear somewhere else. Oh, I'm noticing that, you know, the cottonwood trees aren't turning yellow at the right time of year anymore. Okay. I can put that fear somewhere else. And for sure there's, there's some quality of that where it's like, okay, I've dealt with that set of fears and I've extrapolated that out to the extent that I need to, in order to stop thinking about it to some extent.

Ariana Brocious: Do you think your writing also helps the reader do some of that, sort of navigate their own feelings around eco anxiety or grief?

Paolo Bacigalupi: I hope not. I hope I leave them so profoundly disturbed that they actually do something. I hope to wreck their home. Like, I mean, I hope to make them feel like the walls of their home are closing in on them. That nothing that they live in is stable or secure. I hope that they are horrified and think, oh, just because today looks good doesn't mean tomorrow is safe. That's what The Water Knife is for, something like that is for, is to leave them so profoundly disturbed that their home no longer feels like a safe place. And they have to start engaging with the external world that like is sending us signals all the time but we continue to find our ways to ignore that either with our, you know, our Netflix or our Instagram or whatever the thing is that's like keeping us involved in the slap fight of the moment or whatever it is, instead of like looking at the big pattern of like, where is our future headed?

Ariana Brocious: Well, I'll say The Water Knife is very effective in that way, especially if you live in the Western U.S. So I'm curious though, elsewhere in this episode we speak with Denise Baden, who's the editor of this No More Fairy Tales anthology, and she says that fear is an effective driver of plot and it can be an entertaining tool, stories that instill fear, but that overall that's counterproductive in actually generating the change we wanna see like in the climate emergency, for example. So I'm curious what you think about that perspective.

Paolo Bacigalupi: I am sympathetic to the idea. I think that if you want to create change in a democratic society, people have to believe that there is actually a threat. In order for them to believe that climate change matters, they have to extrapolate forward into what climate change is, and they have to have that grounded well enough in their world, in their physical spaces that they. It's no longer an abstraction that they think, oh, maybe in 30 years they have to think maybe my property values are gonna die in five, and that's a problem. And so we need to deal with it. If you don't make it visceral and bring it into their world, I'm not sure that you get the kind of democratic sort of upwelling of concern that moves politicians or that gets people onto electric co-op boards or planning boards or planning commissions and stuff. I think in very young people, I think that there's a stronger sense of emergency, but I think that there's a huge value in generating unease in people who are otherwise feeling like I can probably skate by. You really want to kind of illustrate like, well, what happens if our insurance industry completely collapses because we didn't do the risk analysis correct on how hurricanes and other climate emergencies are going to damage our infrastructure. You want them to feel like, oh, just because I live in a safe space doesn't mean that that actually is a safe space. You want it to impinge and impinge and impinge.

I know that some people sort of say that if you present people with a really negative future, that that either creates a sense of despair or it creates a sense that they think that that's the way it's going to go. And so they sort of start planning for that. So that's kind of where you see the preppers. Like they read enough dumb apocalypse novels. And then you have all these jacka**es out there with their canned food and their guns like planning to white knuckle it while the civilization collapses, and they become kind of a, creating their own future based on their imagination. And so I get the critique of, you know, dystopian stories or apocalyptic stories. I mean specifically apocalyptic more than, you know, dystopian. But like that these things might be bad or motivate people in bad ways or create the wrong framework for people to understand how to engage with big challenges. It's totally possible. I think though that there is this element that a well-written story of warning can create a sense of unease and a sense of awareness that otherwise doesn't exist for people. I've had readers write to me and say, I decided not to move to Phoenix because of your book. And you're like, good. You shouldn't move to Phoenix. It's not a sustainable space. Like it's not being designed in a sustainable way. That means something finally to them. And so that means that they're suddenly alert and engaged in a way that they weren't before. So I don't dismiss the critique of, you know, dystopian fiction or negative stories or unpleasant future stories, but I don't think it's an encompassing critique. I don't think it's the only, you know, way to look at those things. And I don't think it's the only outcome.

Ariana Brocious: Well, so as we wrap up here, we've talked about. The value you see in painting dystopian futures and how that can serve as motivation. But a lot of the things that we've, the stories we've been talking about today are set in what I would call like, you know, the near future. So they're not really, really far, they feel kind of like maybe a few decades out. And I'm wondering with a sort of more hopeful framing, do you think by setting these stories in that. Not so far away future, you give the reader maybe a little bit more boost toward, I dunno, a stronger sense of agency or a drive to act because either they feel the pressure of like, oh my gosh, it's getting scary, this is coming right now, or, oh, I see that this world that you've painted that's utopian isn't actually that hard and we could actually achieve it.

Paolo Bacigalupi: So speaking specifically about trying to create positive futures and trying to create inspirational futures, I think that there's a quality where you do want to be thinking about attainability and you also want to think about not creating a consolatory future, like one that tells you that it all works out. Somehow in the future we have, you know, magic power that runs everything. And magic, clean power makes everything magical. And I think that science fiction, that's one of the dangers actually of writing sort of like positive fiction or even future fiction of any kind that assumes that the human race continues is fairly optimistic in a lot of ways. And so if you write a story that says we live on Mars, or you used to write a story that says, oh, all of these other things have happened, it sort of ignores the gap that we have to make it across. And so I think that, yeah, if you're gonna write inspirational fiction about the human race surviving and thriving, that you do want to kind of make it within the near range of where we're at so that it actually reflects back on us and actually, you know, is understandable. And so yeah, no, I think it's very important that you tell that story in a way that it feels relatable and, and relatively close and, and engages with the, the present infrastructure that we have and the present world that we have as well. And doesn't live in denial of, well, we're starting from here. We need to get to there.

Ariana Brocious: Something that we can achieve. We have yeah, a path forward, right?

Paolo Bacigalupi: Very much.

Ariana Brocious: Paolo Bacigalupi is an award-winning international bestselling author of speculative fiction, including The Water Knife, the Windup Girl, and many more. Paolo, thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Paolo Bacigalupi: You bet. Thank you.

Greg Dalton: As we mentioned, Paolo’s story, “Efficiency,” appeared in the anthology “No More Fairy Tales: Stories to Save Our Planet.” Denise Baden [BAY-den], a sustainability professor in the UK, edited the anthology. For years she’s been running the Green Stories fiction competitions and written her own climate fiction. Given that so much climate information is based on scientific reports, I asked her how storytelling can reach people in a way that data can’t.

Denise Baden: Well, I found it myself just being a writer. Sometimes when I'm trying to explain an idea and you're trying to say how it affects different kinds of people in different situations, it comes across quite quickly as boring and tedious.

When you write it into a story, then it's part of the plot and you can actually show climate solutions and how they might affect real people. So it might be, say, public transport replacing private cars. How might that affect someone with children? How might it affect a commuter, how might it, you know, affect different kinds of people?

So, you can show it through their everyday lives. So it's entertaining. And you can identify with it. The wonderful thing about fiction is you are entering into someone else's world and you are experiencing the world as they experience it. So it's a lovely way rather than talking in dry terms about stakeholder analysis, you can show it and showing is always more entertaining than telling.

Greg Dalton: Right. That's what they teach you in high school writing. What makes fiction so powerful? I guess, you know, you're entering that world of someone else and perhaps it's because of that character attachment that we don't have perhaps in the news.

Denise Baden: The thing is about climate fiction, it tends to raise awareness of what is wrong. And of course that's a necessary step, but it's certainly not sufficient. And I've done a fair bit of research into this and how people respond to climate change communications and positive stories with solutions, whether it be in the field of news or education or fiction, actually engage way more people than more catastrophic tales of what will go wrong if we don't do anything. Some people are engaged by that. But just as many people are switched off, they might feel manipulated or they'll go into denial or they'll feel guilty, or they'll just feel scared.

And all these responses are quite rational responses to have in the face of something that is quite scary. So if you just put out the problems, I see it as revving an engine engine without being in gear. You're kind of creating quite a lot of negativity, but you're not really going anywhere. So I've had research where I've exposed people to flash fiction, positive solution focused or more catastrophic focused. And the results were really clear. The more negative ones raised awareness, but if they did lead to any behavioral intentions, it was more like something should be done. Whereas the ones where you show characters actually doing something or you show solutions, it leads very much more to, oh, right, I can see what I can do. I will now do this. So I like a more positive approach, because I think you engage a wider audience, and it's just been shown to be more effective. The kinds of behaviors you might get just by scaring people probably aren't the ones that these climate fiction authors are hoping for. You know, they're just as likely to go off and, and buy up all the toilet rolls in the supermarket or get themselves some guns or go massively anti-immigration or self-protective. Because that's how we tend to respond when they're scared. Whereas when you make people see what can be done, they feel much more expansive and it leads to much more proactive positive behavior change.

Greg Dalton: That fear triggers our lizard brain, which wants us to kind of store food and guns or go to some dark places though clearly doom and denial, I've heard people say, seem to sell. There's two ways that activate clicks and activity. One is the doom you're talking about and the other is the denial. And that's certainly where we've seen Hollywood and feature films. In your editor's note for No More Fairy Tales, you write, “this anthology has a clear purpose to inspire readers with positive visions of what a sustainable society might look like and how we might get there.”

Without sounding a little jaded myself, some of those stories read a little kind of rosy, optimistic, uh, and make me wonder if readers might sort of say, Ugh, you know, that's Pollyannish. We're not gonna get there. What do you think about that?

Denise Baden: So, I've come across this term through-topia. We know dystopia. I think most films and books set in the future are dystopian. We've heard about utopia, which is kind of unrealistic. I love the term through-topia because what it does, it allows us to imagine what a sustainable society might be like if we do it well and then works backwards from there to show you how you might get there. So we already know a lot of the solutions. And these solutions are all in No More Fairy Tales. They're carbon drawdown, whether it's through nature-based means, sea grass, kelp tree planting, or direct air capture and storage. It's through trying to reduce consumption. Or high carbon consumption. And there's a number of ways you can do that. Personal carbon allowances or personal carbon trading, green taxation. Switching our metric from the gross domestic product, which measures basically consumption and production to say a wellbeing index. Some countries are doing that now and we have a big call for that in, in the UK. So there's all these kinds of different solutions. We've got one story in there. Give the Ocean Nation status and then allow it to charge for its services. So some of them are quite radical, some of them are really going on at the moment and we're just drawing them to attention. Some of them are cultural. But when you look at the utopian idea, you have to look at the order in which you do things. So one story in there is set in the citizen's jury. It's called “The Assassin.” And it's eight people in a citizen's assembly kind of thing, and they're debating climate solutions. And then there's a murder. So the murder is the entertaining bit. It's the who done it. It pulls people in, but it gives you an opportunity to debate these climate solutions and be exposed to them. But the biggest climate solution of all is that democratic process. The citizens assemblies. So we've known for decades, haven't we, what we need to do. And we've had the ability to do it, you know, for a couple of decades. Although we've, we've got much better, but we haven't. And part of that is our democratic system ties us to electoral cycles. It incentivizes short-term thinking. It's subject to vested interests, so all of these things make it very difficult. I personally believe our democratic system is constitutionally incapable of prioritizing climate crisis over things like jobs or more immediate ones, but the citizens assemblies, there's been so much research done now and they're really taking off. I mean, in Europe, they're doing brilliantly. In Northern Ireland, in the UK, I've got a climate assembly going on at the moment, but where I live, they have now been shown that if you give people access to independent information, you give them time away from their job and family to debate it. They will come up with good, well considered, informed long-term decisions. The only issue is that in most countries, they don't have power.

Greg Dalton: That seems like a key. Seems like a key one. Yes.

Denise Baden: So for me, that's a key solution. And a lot of other solutions like renewable energy, require us incentives. So we could, for example, adopt a more sharing economy. Not everything we use, almost everything we use isn't being used at any given moment. You know, how often are we actually in our car? There's all kinds of fashion swap and libraries and driving apps that enable you to share, but the incentives aren't there. If you had something like a personal carbon allowance where if you had a certain amount and if you went over, you'd pay extra, suddenly all these different sharing apps would get massive support and then they'd be able to deliver a great service, a great public transport service because it would get that, it would go past that tipping point. It would drive innovation into sustainable technology and practices and products. So I would dispute that any of the solutions in there are pollyannaish, I think we just need to do them in the right order. Push the levers in, in the right place.

Greg Dalton: At the end of each story you include a link to information. How do you gauge the success or outcomes of this anthology and its related educational materials and stories? We hear this all the time, you know, some people say the same thing about podcasts. How does the world change? So what? People read a story, listen to a podcast.

Denise Baden: Okay, so I've got a couple examples for you. One of the short stories is adapted from my first novel Habitat Man, which is based on a real garden consultant who gave up his job in the city to help make people's gardens wildlife friendly. And he falls in love and he digs up a body. So there's a romance, there's a mystery. So I condensed the sort of turning point into a short story, but I have research from the book where we had 50 readers. And we asked them to read the book and then report on how their practices changed. And then we went back to them a month later and 98% had adopted at least one green alternative as a result of reading the book. So common ones were obviously things to do with what you do in your backyards, but there were also things like, with the body, I used it as an excuse to talk about natural burials and I had several people write to me saying they've changed their will to specify a natural burial.

Because actually your traditional burials with your mahogany hardwood coffins, you know, and the cremation are really high carbon versus natural burials. I created a lovely scene where people were moved to think, that's what I'd like to do.

When I was writing the natural burial chapter, my mom actually was dying. So I think that lent an air of poignancy to it. And when I buried my mom, I did exactly what I did in the book. We had a woven willow coffin. We planted her in the ground, no formaldehyde, which poisons the earth. We just let the ecosystem do its bit and planted a tree there and trees grow really well in that environment. So it made me feel better feeling my mother was sort of nourishing the ecosystem rather than destroying it.

And another example, and I still have to see how this one pans out. I guess one of the more out there ideas in No More Fairy Tales stories to say the planet was the idea of giving the ocean nation status.

Greg Dalton: Oh, I liked this part in the book.

Denise Baden: Yeah. Well, there's many things. I mean, there's many countries now beginning to, I think there's rivers who've been given nation status in New Zealand. I think Ethiopia's done something. So that was the idea. And we opened it up in one story. We showed how it had developed in another, and then we do a 60 years on what it now looks like. And the person who really was the driving force, Steve Willis, behind this one. He was at the Ocean Summit last December and he was talking about it and he got a lot of traction and they said, right, that needs to go on the agenda at the next World Ocean Summit. And so I'm really looking forward to seeing if anything happens from that. I mean, it won't happen exactly the way in the book, but it planted a seed and I'm yet to see how it grows.

Greg Dalton: Denise Baden is Professor of Sustainable Business at the University of South Hampton and Leader of the Green Stories Project. We've been talking about No More Fairy Tales: Stories to Save Our Planet. Thanks so much, Denise, for coming on Climate One.

Denise Baden: Well, thank you very much for having me.

Greg Dalton: Coming up, an effort to make climate fiction more diverse and intersectional:

Tory Stephens: The genre is changing, but many of the stories I read did not have frontline community members where the climate impacts are really impacting their life right now. So I really wanted those folks to be represented.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking about climate fiction as a way to understand and inspire solutions.

Ariana Brocious: The nonprofit online news outlet Grist has been running a climate fiction competition for the last three years. We’re going to hear an excerpt from one of the winning pieces, called “The Cloud Weaver's Song,” written by Saul Tanpepper and recorded by Curio.

There was once a beautiful city called Asmara, high on the Kebessa Plateau, a mile and half into the sky. Asmara was a wondrous place, where for a hundred thousand years the clouds drenched the air each night and rains nourished the soil. The rivers that flowed down its escarpments fed the lowlands and eventually emptied into the sea.

The ancient name Asmara comes from the phrase arbate asmera, which in the original Tigrinya means "the four women who made them unite." Many centuries before, this land had been under constant threat from a common enemy. Now, as before, it was the women who brought the clans together to defend against this new danger. For a while, Asmara became a sanctuary to anyone seeking refuge from the Great Drying.

But the heat and drought were unrelenting foes, and they drove more and more people to the city on the plateau. Week after week they came. Year after year. And because there was only so much land to hold them all, war became inevitable. For a hundred years, the fighting waged.

Now, just as there is no amount of conflict, no matter how bitterly fought, which can alter the course of nature, no volume of human blood could quench the thirst of the Great Drying. The deserts continued to expand, spreading until they reached the very ankles of the beloved city on the plateau.

It is said that necessity makes us do what we must in order to survive. Eventually, the rains began to evaporate before ever reaching the ground, and the rivers dried long before spilling into the sea. So, the women of Asmara rose again and taught themselves how to harvest the nightly mists with threads spun from molten glass. For a while, it helped.

But the thirst of the Great Drying was like that of the hyena’s: never slaked. Not satisfied with stealing the fogs from all the lands beneath Asmara’s feet, it reached up and took them from her, too.

Once more, necessity made the people do what they must in order to survive. The peaceful Afar had long since retreated into the clouds by building towers that reached even higher than the Kebessa Plateau. Now it was their brothers’ and sisters’ houses burning to the ground. And so they welcomed them all into the sky, where the mists were still plentiful and ripe for harvesting.

Semhar Ibrahim was a weaver of webs. Each night, she assumed the skin of a spider and set out from her little hole to spin her delicate threads. High above the ground, where the clouds formed, she carefully laid out line after endless line, each one as thin as a hair and as long as a mile. To harvest the dew that condensed upon them, she gently plucked each string, sending them vibrating along their entire length. Each wire carried its own unique note, and when played altogether they sang the song of the Weavers. As the droplets traveled down the wires, they merged and grew fat, creating a delicate river suspended in the sky. This is how the people harvested the clouds so that all might live. And each night, when you heard the tune, you would know how heavily laden the wires were with mist, depending on how melodious or melancholic the notes sounded.

Ariana Brocious: That was an excerpt of the audio recording of the fictional story “The Cloud Weaver’s Song” by Saul Tanpepper. Find a link to the full print and audio story in the show notes on our website. Tory Stephens is climate fiction creative manager at Grist, where he’s been running the climate fiction contest called “Imagine 2200.”

He says the concept originated out of a pandemic-era Grist retreat for folks they call “fixers” – climate solutions professionals from across all different fields. Over the course of three days they envisioned pathways to different climate futures, laying out a timeline of the next 180 years.

Tory Stephens: We stuck people in cohorts or five and essentially they plotted a way to get to a clean green and just future by 2200. And so, you looked at these timelines after with their visions and ideas and moments and their timelines were so rich and they weren't just about climate, they were intersectional. And they were so much on the social justice side of things about abolition, about rewilding and the land back movement for indigenous folks and reparations for Black folk. And so, when we walked away and kind of digested all the different timelines that these folks put together, what we saw was that there's a lot of climate fiction that doesn't pull in this kind of social justice angle.

So we knew that when we did climate fiction at Grist, we wanted to infuse it and make sure that the prompts and the architecture of what we're asking for in our stories has that intersectionality has those other issues that frontline communities care about.

Ariana Brocious: Let me jump in here because this is a perfect pivot to the next question. So, the contest rules for this fiction writing contest state “Imagine 2200 was inspired and informed by literary movements like Afro futurism and Indigenous, Latinx, Asian disabled, queer and feminist futurism, along with Hope Punk and solar punk. We hope writers of all genres look to these movements for inspiration and urge writers within these communities to submit stories.”

And I wanted to read that because I think it's important that that's actually explicitly stated in your brief, essentially. So tell us more about that focus on intersectionality of climate impacts, not just the writers that you're seeking to hear from, but the stories that they're telling. Why is that so critical?

Tory Stephens: Yeah, I think it's really critical because that's the lived experience that these folks have on the ground. You know, when you are a queer person from Louisiana, a black queer person from Louisiana, you can't just separate those different identities that you have intertwined and that make up you. And so we want characters that are rich and layered like that because those are the people that are living like the first piece is that. We wanna see everyone reflected in this fight for a better climate, right? And so what I found when I was reading a lot of climate fiction, and this is changing, I would say, but you know, just reading through the genre, I found a lot of stories where I sometimes I call the characters Lego people. And what I mean by that is that a person, their identity is just, it's about the world building and what they're going through, and less about the identity of the person and how they would react to the world that they're moving through. So you could pop off the head and put it on another person, and their gender wouldn't matter too much. The story wouldn't change too much. The cultural things that they may have in their life, the food they eat, the landscape that they live in. All those things wouldn't change that much because the author is trying to get across like the plot of the world. But for us, the character is who's moving through that world and the part for us that's really interesting is their identity. The genre is changing, but many of the stories I read did not have frontline community members. You know, folks that are living in the Caribbean, folks that are living in New Orleans, right on like the water's edge and other spaces where the climate impacts are really impacting their life right now. So I really wanted those folks to be represented. And also the call is also to put out the bat signal to be like, Hey, this is a safe space for you to write your stories, write your heart out, send them to us. We want those kind of stories.

Ariana Brocious: That's great. So Grist is an independent nonprofit news outlet focused on climate solutions and a just future. How does leading a climate fiction contest fit in with that news and journalistic mission?

Tory Stephens: Yeah, that's a great question. It's one that I got from the upper folks at management here when we were first launching this. Grist is great at news. It wins awards, people are using our stuff in academic research. Politicians use it to kind of make their case on the hill sometimes. And so, the thing we did notice though, is that we've talked and we've done polls and we''re engaged with our audience and one of the things that we found is that there's folks who just don't like the news.

They wouldn't be our audience, but there's folks out there that we've come across that are just said, the news is so bleak that I just don't engage with it. And it's kind of interesting when I hear that because we often lead from a solutions angle and a hope angle and like a can-do attitude, but still the kind of news itself has been painted by these folks as like a place that they don't wanna spend their time because it's negative.

Maybe they're just bored by the news. Like it's just not the way they get their orientation. And so what we found is that, so many people are story driven. So we wanna reach all people around the climate crisis and talk about climate solutions, the hope and justice side of things. And yeah, news is where we started, but we would also like to reach all these folks in the literary community. And sometimes that overlaps with like, there could be a news junkie and also in the literary community. There's these people who just would rather read a really beautiful story that articulates the world that we want in need and that can help them kind of envision how they wanna plot their next, you know, life choice or even just have a nice story to read.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, that resonates a lot. I mean, I'm someone who reads a lot of news during the day for my job, and then at night I cannot, I just read fiction because I just wanna escape. And it doesn't mean it's always uplifting. You know, fiction has a lot of tension and moods and things, but yeah, I just cannot sort of be in the real world anymore.

Tory Stephens: It's often misunderstood that Imagine 2200 is like focused on utopia. And I would say that our stories are not just utopian stories. They're sometimes through-topia, which is like more of a new term that's coming out of the UK where, you know, it's showing how you get to that other side, or in the midst of changing and going towards like a world that is full of abundance, hope and justice. And then also we have like ones that are questionable how hopeful they are. They do have hope. They just have hope that looks very different than what a western kind of eye sees as naming hope.

Ariana Brocious: There are other restorative themes running through some of the winning pieces like LGBTQ, acceptance and interspecies respect. So I'm wondering if you've heard from the writers or just as an editor reading them how you think writing the stories for the writer themselves might make them more hopeful about these various futures climate particularly, but these other important aspects as well.

Tory Stephens: Yeah. I love that you asked that question because that is like the, I guess I'll call it a wild card. It's the part when I was envisioning like we, I had the audience in mind, when I was building this was about how it would be received in the world and how would people read the stories? And I had a lot of anxiety about that because it's a brand new thing that we were launching. And you know, what I've come to learn is that we've had a real big impact on the folks that are engaged with us from the writer side of the community. You know, many folks reach out to us and say, I have been writing dystopian stories for so long, it's like second nature, that's the way, that's my clarion call to the world on how we get this right. And I hadn't spent a lot of time envisioning, what if we get this right? Like, what would that world look like? So yeah, a lot of the writers will say that they haven't really spent time envisioning a future that is, you know, working for us. And so, I think it is, it's such a powerful thing for that side of things.'cause again, like I said, it's like a wild card. I didn't even think that. So now just to do the numbers, we've had almost 3000 stories submitted over three years. We're in touch with those writers. We shuttle and put opportunities in front of them that we come across, because we're now connected with a lot of different writing communities. And this is kind of like the tough part about Imagine is we only publish 12 stories out of, you know, this year we got a thousand, we're gonna publish 12. So we really want to help those, like I would say that there's hundreds of great stories out there, some that need a little bit more help. So we try to send them resources for where they could, you know, workshop that story. And then others where it's just not the right fit for what we're doing. But it's an incredible story. So we encourage them, Hey, like you don't have a bad story here. You just don't have an Imagine style story that we're looking for based on the prompt that we put out to the world.

And so we encourage them to submit their story elsewhere because I mean there have been some brilliant stories that when I'm looking through our files, I've reread myself, you know, I'm like, oh, is this the work? It is the work. But yeah, when I'm looking at a story from year one that I really hope is like being published somewhere else. It gives me all the feels.

Ariana Brocious: What was the most surprising interpretation of our future that you've read so far from the submissions?

Tory Stephens: Ooh, that's a really good question. I think I'm gonna go with the, the Greenland shark, the um, the last of the Greenland sharks, because it was really hard for me to see the hope in that story.

Ariana Brocious: And I'll jump in and just tell listeners that the story is sort of, it focuses on the four remaining individuals of species on earth, right?

Tory Stephens: Yes. Yes. And they have a psychic connection with each other. but like it is, it is very bleak. Four individuals left, right? And so, wow, it was really hard for me to find the hope in that, you know? I mean, I think that story did a lot of work in having me reflect on what hope means, and it just opened the door for that. Hope to me now is a word that needs to live in a space between me and other people. So what I mean by that is that, and this might sound weird, but I want to ask people, what does hope look like to you?

And then I want to have a conversation. I think we need to have more conversations around what hope looks like, because I think it can be quite superficial, even for myself at certain times. And I think I've deepened the level of understanding I have of the word hope by talking with people and being in community with people and explicitly being like, let's talk about hope and what it means to you. I believe that hope is something that you have to explore collectively.

Ariana Brocious: That's wonderful. I think we'll leave it there. Tory Stephens is Climate Fiction Creative Manager at Grist. Tory, thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Tory Stephens: Thank you.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One, we’ve been talking about fairy tales and fear in climate fiction narratives.

Ariana Brocious: Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe wherever you get your pods. Talking about climate can be hard-- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. On our new website you can create and share playlists focused on topics including food, energy, EVs, activism. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Ariana Brocious is co-host, editor and producer. Austin Colón is producer and editor. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Wency Shaida is our development manager, Ben Testani is our communications manager. Our theme music was composed by George Young. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.