Policy Whiplash: Checking In With Labor Unions

Guests

Roxanne Brown

Lee Anderson

Lara Skinner

Summary

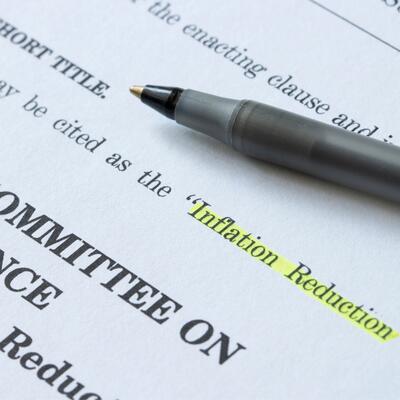

The past few years have seen a seismic shift in energy and production policy in the United States. After the passage of laws like the Inflation Reduction Act, money had begun pouring into clean energy manufacturing and deployment.

“Embedded within those pieces of policy was industrial policy, really beautifully woven throughout, to create a landscape and a foundation for industry to grow in the United States into the future,” says Roxanne Brown, vice president at large at United Steelworkers.

As jobs in the clean energy industry were on the rise, so were unionization rates. In 2024, clean energy union jobs reached 10% of the industry workforce, outpacing the private sector as a whole – though still far lower than the peak union membership rate of 35% in 1979.

The United Steelworkers union — or USW — has been an environmental and climate advocate for a long time. They were even a founding member of the Green-Blue Alliance, which brings unions and environmental groups together. USW backed those policies. “It's like the Biden administration heard everything that we had been asking for,” says Brown.

Now, the current administration’s budget law and executive actions have rolled back as many of those policies as they could. That has hit the clean energy industry hard, and has had a detrimental effect on the union jobs within it. “All of that was ripped from these companies and, and the jobs associated. And now we have a ‘closed for business’ sign,” says Brown.

“I would say our union's input has been zero, none,” says Lee Anderson, director of governmental affairs for the Utility Workers Union of America, when talking about the organization’s input in policy decisions with the Trump administration.

Utility workers are often the unsung heroes of the energy industry. They take care of the pipes under the street, they put up the lines that bring electricity to our homes, and they help make that energy in the first place. The Utility Workers Union of America, or UWUA, represents those workers.

Their work has not only been impacted by the political climate, but also the climate crisis. When utility workers are called in the aftermath of more frequent storms, they find “live wires everywhere. Sometimes there's live wires lying in four feet of water. So it's quite dangerous work,” says Anderson.

The Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act – which became New York state law in 2019 - set legally binding climate targets. It also explicitly included job transition training and a goal to minimize workforce disruption. The programs it created might offer a glimpse at what “worker first” climate policy could look like on the state level.

“We pulled together a number of building trades and energy unions and other unions and said: would you engage in a research policy, educational process with us, to put together a job-centered plan to address climate change in New York,” says Lara Skinner, executive director of the Climate Jobs Institute at Cornell University.

The Climate Jobs Institute has helped influence policy wins for organized labor and clean energy in New York and Illinois, and aided in creating state based coalitions between unions and environmental groups. They hope to replicate their New York and Illinois success all over the country. Skinner says, “We can actually support unions and union coalitions in other states to develop similar plans to win worker centered climate victories.”

Resources From This Episode (3)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Kousha Navidar: Okay. So Ariana, this week's episode is about unions and it's about energy, right?

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. Yeah.

Kousha Navidar: So our buddy Austin, who's on the show sound engineer producer, uh, sent me a video that I wanted to play you of an old union protest song. You ready? Okay. Yeah, hit it.

Simpson’s Clip: Come gather around children. It's high time he learns about a hero named Homer and a devil named Burns.

We'll march to, we drop the girls and the fellas will fight till the death. Fold like umbrellas.

So we’ll march day and night by the big cooling tower. They have the plants, but we have the power.

Kousha Navidar: Wow. I bet you can guess what that's from.

Ariana Brocious: Uh, yeah, that's Lisa Simpson.

Kousha Navidar: That's Lisa Simpson. It's from an episode of The Simpsons, where Homer and the workers at the nuclear power plant form a union and go on strike.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. I mean, I wouldn't consider that like a classic union ballad.

Kousha Navidar: Well, fair enough. It is a protest song about labor and energy.

Ariana Brocious: All right. All right. I'll, I'll give you it. I'll give you that one. Um, but yeah, that's what we're talking about today. Labor unions, clean energy and how the Trump administration's trade policy and incentive rollbacks are affecting unions.

I'm Ariana Brocious.

Kousha Navidar: And I'm Kousha Navidar..

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One.

Kousha Navidar: In the past couple of years, union jobs in the clean energy sector had been on the rise. And as it stands now, nearly 10% of the workforce in the industry is unionized. Which actually outpaces the whole of the private sector.

Ariana Brocious: That’s also at a time when clean energy jobs were on the rise in general. But for a little perspective: Membership in all unions in the US peaked in 1979 at about 35% of the workforce, so it’s still down from its historic levels.

Kousha Navidar: Yes. And that rise in clean energy jobs is thanks in large part to the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure and Jobs Act - which became law during the Biden administration. They funneled money to all kinds of projects – battery factories, solar farms, and commercializing technologies to decarbonize the industrial sector.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, though a lot of that money went to red states, most of which are hostile to organized labor. And even though districts that voted for Trump were seeing those investments and jobs, in the last several months the Trump administration has rolled back many of those policies that were spurring growth.

Kousha Navidar: And because of those rollbacks, entire projects have been put on hold or even cancelled. That's taking work away from everyone, including union workers.

Ariana Brocious: Not only that, the administration has basically gutted the institution that is supposed to protect labor rights — the National Labor Relations Board, or NLRB.

Kousha Navidar: So put all that together and it feels like a good time to check in and see how unions are responding to the current moment.

[music change]

Kousha Navidar: First up, I spoke with Roxanne Brown, Vice President at Large for the United Steelworkers.

Ariana Brocious: It takes a lot of energy to produce steel, and it’s one of these hard-to-decarbonize sectors we talk about. So it may surprise some people: their union has been an environmental and climate advocate for a long time. They were even a founding member of the Green-blue alliance, which brings unions and environmental groups together.

Kousha Navidar: And that’s right where we started the conversation.

Roxanne Brown: It really started from a safety and health perspective, and stemmed from the disaster that happened in Denora, Pennsylvania, not too far from where I sit here at our headquarters in Pittsburgh,

Kousha Navidar: Hmm. And when was that?

Roxanne Brown: 1948. there was a temperature inversion. So Denora is kind of in a valley, you know, here in, in this part of Western Pennsylvania. And there was a, a zinc, um, facility and a, and a steel mill, and there was a temperature inversion And it, it basically trapped the, the pollutants from these industrial facilities. It was a significant industrial disaster that created this smog of toxicity. Around the town of Denora and 20 people died. And a whole bunch of people got sick. But the people who were most directly impacted first were workers, who worked at, at these facilities. And so, you know, for us that was, a wake up call on a lot of fronts. I mean, safety and health is a core issue and core fight for any labor union, right? But this created a different way for us to think about it, that extended to the environment and the role that the facilities that our members work at,have when it comes to being a good environmental steward, right? Where the first line of defense goes into the communities where they live, impacts their neighbors, et cetera. And so we decided to lean in, which was not super popular at the time, with industry. But we leaned in and leaned in so much that we took that and extended it to the development of the first iteration of the Clean Air Act in 1963.

Kousha Navidar: Wow. Yeah. And let's jump to today. 'cause clearly from your perspective, it's had life changing impacts. How has climate affected United Steelworkers members in the workplace today or for the time that you've been there?

Roxanne Brown: You know what it's been, an evolving thing, right? Because it, I think, has impacted our, our members in different ways across our membership between here and Canada, right? Because we're an international union, in the United States and Canada and the Caribbean, and I think if you talk to our folks in Puerto Rico. Right where we represent a lot of folks, Puerto Rico has been so hit by natural disasters right? Over the last 10 years. It's like, the hits keep coming from hurricanes and superstorms to our oil workers and the Gulf whose refineries have been impacted again by Superstorms. And that has taken their refineries offline, and then they've had to join with local environmental groups to help folks get back into their homes safely, right? So steelworkers joining with environmental groups on the ground, again, this is where the health and safety comes in because our folks are trained around the pollutants and the toxins that exist at refineries. being able to say, Hey, community, I'm your expert here, join with me and I can help you get back into your home safely. Right. So it runs the gamut across so many of our different sectors. But I would say the biggest way that we've been impactful in this space is by kind of kicking. The companies that our members work for in the butt a bit to make investments, you know what I mean? To, to, to make investments at their facilities because

Kousha Navidar: Like investments to protect workers, or Tell me more.

Roxanne Brown: Investments to mitigate their pollutants, you know, so starting from the Clean Air Act of 1963 to 1970 to 1990, and then every rule and regulation that has been promulgated since then, right? That has to do with emissions of industrial pollutants, making the active decision to lean in. Right. And making sure that those regulations serve the purpose that they are meant to serve, which is to help clean up these facilities in the communities,so that it drives these facilities, these companies to make investments. So if they're making those investments, they're not leaving, they're gonna stay for the long term, you know?

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, yeah. And I'm so interested in the global footprint angle that you brought up, um, Puerto Rico. Uh, it makes me wonder whether protection from extreme heat or other weather events come up when you're negotiating on behalf of your members.

Roxanne Brown: Oh my gosh. Totally. You know, we are, I like to say we're the, the union of, of all of God's creation because we represent workers and, and literally every single sector that you can possibly imagine, from steel to refining, to cement, to chemicals, every single one of those glass has significant amounts of heat attributed to the work that's done. And so it's a consistent thing that we have to work on as a union. But also, again, this lends to regulation, and policy and heat standards and something that is still meat that has been left on the table by this current administration and not moving forward with a heat standard that will protect workers at the workplace, right? from both the heat that is associated with their production, but then when it's 120 degree day in Arizona. Right. the impact of that heat on workers and communities as well.

Kousha Navidar: Well, talking about the, the policy angle to it too, the, the union has pushed back against groups like three 50 dot org's break free from fossil fuels. So where do you draw the line, or at least how do you, what issues did you see with that agenda, for instance?

Roxanne Brown: Yeah. We just, we're not. We're not in the practice of picking winners and losers, you know? Um, and when it comes to energy policy, we've just solidly been for now, decades and decades in the, um, all of the above, uh, category. And, and it's also because we represent 30,000 members in the refining and petrochemical sector. Right. And so this again, is where the whole notion of investments and helping to move policies that drive investments in industrial facilities comes in for us, right? So we're not gonna say, you know, renewables should trump the refining sector because that would be a detriment to our members' jobs. But we will say those companies are responsible for making sure they're making investments in technologies and pollution mitigation technologies that will reduce their emissions and make them cleaner. Not just for the health of our members, but the health of the communities that they are operating in. And also just the country and the world ultimately.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. And, and when you mentioned you, you're not trying to pick winners here, uh, I'm sure. Especially in this current administration where there's so many cuts or, or like pivoting from what the previous administration had promised. you're navigating a lot, I guess, and I'm thinking about Trump shutting down wind farm construction, which I'm guessing uses a lot of steel. I mean, how do you navigate that?

Roxanne Brown: We are so supportive of the deployment of renewables technology. And, and you highlighted right, a very, very key reason why we would be, we're the steel workers. Right. Um, and you know, those onshore and offshore turbines require, you know, tons upon tons of steel and copper wire, which our members mine copper and make copper. They require titanium, they require cement, which our members make, right? So one turbine, whether it's onshore or offshore, is an industrial map. And has the capacity to be an industrial map in the United States, but unfortunately, largely because of the policies that really hasn't supported tapping US industry to deploy those technologies. It's been bringing a lot of that stuff from overseas and the irony of that Right, which is just crazy to us. You're, you're shipping in tons and tons of steel from China. Or Brazil to go into an offshore turbine or an onshore turbine, rather than sourcing it from the United States where you don't have those emissions associated with shipping. There's a facility that US Wind has propped up in supports called Sparrows Point Steel.

Kousha Navidar: Mm-hmm.

Roxanne Brown: Now this project is on the grounds of a former steel mill, Bethlehem Steel Mill in Baltimore. It's in Port of Baltimore, and this steel mill used to employ 30,000 plus steel workers. In its heyday, it was the beast of the east. Okay.

Kousha Navidar: Hmm.

Roxanne Brown: Today that steel mill obviously is, is gone and everything that came with it in terms of the economic activity. US Wind is now bringing economic activity to a place that needs it and to a community that needs it and is gonna be making really key components for offshore wind. We support that with everything in us, right? Number one, it's hallowed ground for us because of what this site meant for, for our union and our members. But it's also just what it means for the community and the ability to grow sustainable long-term jobs into the future. And to, really help to lend to the environmental sustainability of the country as well.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. Beast of the East is very catchy, I gotta say. That really sticks with you.

Roxanne Brown: That's what it was. The beast of the east, the steel out of that at, out of that mill, went into, the, world Trade Center. I mean it like,

Kousha Navidar: Mm.

Roxanne Brown: it, it's, it's,

Kousha Navidar: It’s far reaching.

Roxanne Brown: It's so far reaching.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. Um. It it, when you mentioned Beast of the East, my mind just went to the Inflation Reduction Act because that name compared to Beast of the East. But you know, it's, it's also germane to the conversation 'cause federal, we're talking about federal policy whip

Roxanne Brown: yes, yes,

Kousha Navidar: Uh, how have rollbacks to the IRA affected your, your members?

Roxanne Brown: It's not been great. And it's not just the IRA, it's also, the bipartisan infrastructure law, right? Um, for the first time in. In more than five decades. Right. Um, we actually had a set of industrial policies that were linked to the Inflation Reduction Act, to the bipartisan infrastructure law, to the Chips and Science Act. Right. You had these three and you know, for policy people, right. Just, just one of those things is life changing, right? but the fact that we had three really robust, well-funded pieces of policy and embedded within those pieces of policy was industrial policy, really beautifully woven throughout, to create a landscape and a foundation for industry to grow in the United States into the future, unions like ours, we talk about revitalizing the manufacturing sector. We talk about the hollowing out of manufacturing that has happened over the last four decades. Right. And we talk about what's needed and how we bring our communities back and how we attract investment to communities that have, have lost traditional industry. And it's like the Biden administration heard everything that we had been asking for, and they gave us these three bills and, and now, so much that represented the promise of those bills is gone. You had, you had cement companies who, were waiting for a long time, their r and d arms, had these ideas about, you know, manufacturing, clean cement or cement that had reduced emissions. And here was the bipartisan infrastructure law that provided, through Department of Energy, a pot of money. To fund the development of those projects and they move forward with them. And then earlier this year, there's an announcement from the Trump administration that they were gonna scale back $3 billion worth of investment,for any clean energy development project. And there were about 24 projects, and the bulk of those were at industrial facilities. And so, the promise of bringing industry and innovation into the future gone just like that. And then the ability of these companies to move into the future in a way that is innovative, that is competitive in the global marketplace, is now a question mark and I keep saying this internally, but it's, why would we go from a posture as a nation of saying the United States is open for business. You come here,you make investments in these technologies,in these sectors that are growing, and we will support you in that. We have the set of resources to support your investment, and you have all these companies coming and saying, oh my God, the United States is open for business. And then all of that was ripped from these companies and, and the jobs associated. And now we have a closed for business sign.

Ariana Brocious: We’ll hear more from Roxanne Brown after the break.

Also coming up: with more frequent and intense fossil fueled storms, utility workers are facing treacherous conditions.

Lee Anderson: There are live wires everywhere. Sometimes there's live wires or lying in four feet of water. So it's quite dangerous work.

Ariana Brocious: That’s ahead, when Climate One continues.

Help others find our show by leaving us a review or rating. Thanks for your support!

Kousha Navidar: This is Climate One. I’m Kousha Navidar.

Let's get back to my conversation with Roxanne Brown,Vice President at Large for the United Steelworkers.

Kousha Navidar: It's not lost on me that USW didn't have to enter the climate space. You, you chose to, but now you have to sell it to your membership or you have had, this is not a new thing. You have had to sell it to your membership. Kind of like how politicians have to sell ideas to their constituents.

Roxanne Brown: Right.

Kousha Navidar: So how do you go about doing that?

Roxanne Brown: Um, I really appreciate that question. Um, I, I really, I really do kisha because it's. It's layered. There's so many pieces to it. And I would say the, the first piece of it is, um, service is a word that we use in, in the labor movement. And so for, for labor unions, our job is to service our members and servicing our members takes a whole bunch of different fronts. And one of those is long-term strategic planning. It is our responsibility to look across the set of industries and sectors our members work in and strategically plan for the future. And I think back to when I first started working on these issues back in 2005.

Kousha Navidar: Hmm.

Roxanne Brown: So the message that I, and we organizationally used with our members on clean energy and climate policy in 2005, we used the word green, green jobs. You would never find me in 2025 saying the phrase green jobs

Kousha Navidar: Oh yeah.

Roxanne Brown: Never. I would never ever, ever, ever use that phrase, because our, our members hear that and they hear, oh, that's not my job.

Kousha Navidar: That's not my job. Yeah. Right,

Roxanne Brown: That's not my job. Right. But today it's clean. And clean just means we're cleaning it up. It's still your job, but we're making it operate more efficiently. We're taking some of the pollutants out of the air. If we could mitigate all the pollutants, that would be great. But it's still, your job just cleaned up. Right? And we've really had to be intentional and smart about updating our language with the time and testing. You know, you, you do, you kind of have to test things but ultimately your members have to see themselves in the thing in order to get buy-in. They have to see themselves in the thing. So if I say clean steel, right, and I unpack for them what clean steel means, then they're less resistant and they wanna find out where does this clean steel thing go? Right? And

Kousha Navidar: they can see themselves in it.

Roxanne Brown: exactly, they

Kousha Navidar: It sparks curiosity instead of um, uh, alienation, I guess.

Roxanne Brown: Totally. And on the strategic planning front, our members wanna know that we are bought into them.

Kousha Navidar: Hmm.

Roxanne Brown: And we are bought into their future. So much of this is about the future, right? I'm working today. Is my job still gonna be here next September? And while you're thinking about that answer is my job, is this facility still gonna be here in 15 years when my kid decides they don't wanna go to college, but they wanna come work where I, so it's about not just talking to them about the thing and helping them to see the thing and, and making them know that we are bought into them and we've got their backs. It's about them knowing that we're also bought into the future, their future.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, And so this is the question that I wanna leave you with. Um, what should climate concerned politicians learn from you around messaging?

Roxanne Brown: Get outta Washington. Get out of Washington. And it's not just, oh, well I go back to my home district, go out and talk to actual people back home. Don't just take the the normal cam back in the district. I'm gonna have these meetings. Those conversations are not the real conversations that that, that they need to be having with folks. Get outta DC. Find real true on the ground people to talk to about not just climate policy but economic policy. Industrial policy. And when I say economic policy, I think one of the biggest things that we miss in this whole climate debate, and especially around the Inflation Reduction Act, is everybody is struggling. The cost of utilities is really high. Nobody was talking to any consumers about how that terribly named Bill, the Inflation Reduction Act, was gonna bring the cost of their power down in their house. Right. Just have real conversations with people back in communities and, and hear what they're concerned about and the words that they're using and, and, and go back to DC and, and then make the sausage to make the policy.

Kousha Navidar: Roxanne Brown is Vice President at Large United Steel Workers. Thanks for having a real conversation with us. I really appreciate it.

Roxanne Brown: Thank you, Kousha. Anytime.

Ariana Brocious: Utility workers are often the unsung heroes of the energy industry. They take care of the water pipes under the street, they put up the lines that bring electricity to our homes, and they help make that energy in the first place.

The Utility Workers Union of America, or UWUA, represents those workers. I spoke with Lee Anderson, their Director of Governmental Affairs, to find out how they are dealing with the energy policy whiplash of the last couple years.

Lee Anderson: For some people the phrase, um, all of the above energy is kind of a throwaway line or a bumper sticker line for our union, for our members. It's the literal truth. We have members who work on every kind of power generation technology I'm aware of. I think that is actually true. Uh, nuclear power plants, coal, natural gas, but also wind towers, uh, utility scale, solar, um, geothermal projects. Um, power storage in the form of, uh, the old style where they pump it up a dam and then later it comes down. Um, I can't think of a power gen technology that we don't have members working on.

Ariana Brocious: And so basically you all are representing those interests equally,

Lee Anderson: Absolutely. Um, we actually, um. I suppose the word is believe, and we think that all of these technologies will play a role in the grid to one degree or another for quite some time to come.

Ariana Brocious: right?

Lee Anderson: Uh, it will, it will change in percentages perhaps, but there will be even coal plants. There will be some that run for quite a long time yet for various, you know, reasons that are often local in nature. But it will be there, uh, in one way or or another for quite a long time.

Ariana Brocious: So we're seeing a large scale energy transition that's playing out and affecting. Jobs that are available in these different sectors, different kinds of energy jobs. We're also seeing a lot of climate induced severe weather, like extreme heat waves or more intense hurricanes, more rapidly intensifying hurricanes. How have those events impacted the safety of your members?

Lee Anderson: Well, large storm events lead to, um, large storm response events, meaning, uh, the folks in our union who are, uh, line workers, um. Which is just what you think it is. People who go in the bucket trucks or climb the poles, et cetera, um, will often go in long caravans to wherever the storm was. Uh, under the, the, the idea of mutual aid that utilities have between one another and help to rebuild whatever has fallen down because of the storm. So you might imagine, well not imagine this actually happens. Trucks going from New York or Michigan or Pennsylvania, driving down to Texas or Florida or North Carolina or wherever the storm has been. We did storm response in Puerto Rico and standing everything back up. Now, as the storms get larger, stronger, more powerful, more damage is done. And so it's not as simple as just connecting the wires back up. Sometimes it's all the poles are knocked down and the transformers blew up, and the damage is greater in, in many ways. And there's a host of dangers in that, of course. I mean, there are live wires everywhere. Sometimes there's live wires or lying in four feet of water. Um, plus the water itself is full of, um, contaminants and et cetera. So it's, uh, quite dangerous work. Um, and the larger the storm, the more work there is.

Ariana Brocious: And you, you've mentioned that there's some dangers associated with this line work, even though it can be kind of a lucrative short-term gig for some of these workers. Um, but there's also just the volume of storms we're seeing, right? So it's not just that the storms might result in more intense destruction, but there might be many storms at once in a given region or in a given timeframe.

Lee Anderson: Sure the limiting factor ultimately is the size of the workforce. Um, if there get to be more storms of greater ferocity and, and a larger number of geographic areas. Theoretically, we could still handle that if we had enough workers to do that. But there's not an infinite number, obviously, of line workers. There is a very finite number, and once they're occupied, they're occupied. I mean, people might say, well train more. Well number one, we're, our economy is at full employment right now. Number two, not everybody wants to climb 50 foot up a pole and handle high voltage

Ariana Brocious: Not me. No, thank you.

Lee Anderson: very, yeah, it's a very specialized trade that very few people want to do, let alone are able to do so. That's the hard limit on, on response.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, so, um. The previous administration, the Biden Harris administration made a lot of investments in the renewable energy. In particular though really energy across the board. This current administration, the Trump administration, has very different priorities about what it wants to see in terms of energy, mostly prioritizing fossil fuel energy. How have utility workers handled this sort of policy whiplash that's been coming out of Washington?

Lee Anderson: Well, um, first of all, starting with the, the Biden Administration's approach, I mean, I suppose some people may disagree, but our perspective was that the, the Biden administration did not actually pick winners and losers among technologies. That they were in favor of supporting all of them, knowing that they would all be a part of the mix, whether you like it or not, for quite some time. So yes, lots of money for wind and solar and geothermal, et cetera. But also things like carbon capture technology for natural gas and coal burners. Also new nuclear power plants. The point was they recognized that it was all gonna be a part of the mix, so they were putting lots of money out there and that was going to turn into lots and lots of projects.

First of all for our brothers and sisters in the construction trades to build and then unions like ours would be operating and maintaining those assets once they were up and running. And so it was an odd period of time there from the, the passage of the, of that bill all the way through the end of the Biden

Ariana Brocious: The Inflation Reduction Act.

Lee Anderson: Correct. Yes. And we saw our employers queuing up to get these dollars and some of them started flowing, then the dollars were all various stages of being deployed. And then inauguration day happens and just immediately overnight, everything starts being pulled back. And we initially thought, well, there will be legal ways to stop that, or they've committed, they can't pull it back. Turns out that was all wrong. They are, whether we like it or not, pulling back dollars all over the board. What, that has meant in practical terms is that our employers are canceling projects because they no longer have the funds to do that. And so our current members will not be doing that work. There will not be more work for future members to do. So in that respect, the workforce and the union is not growing. Um, it's, uh, the, so I suppose to answer your question directly, the way that we've, that has affected us is that the amount and types of work available is just not changing. If anything, it's shrinking and there's less opportunity out there.

Ariana Brocious: Well, that's interesting given that we are at a time when the projections of energy demand are just kind of skyrocketing for what we're gonna need. And that's really gonna have to come from all kinds of energy, as you've said, because the demands are, are expected to be so high. So what kind of input has UWUA had with this current administration over those kinds of decisions as opposed to what you had during the Biden Harris administration?

Lee Anderson: I should be careful and speak only here for our union, though I suspect it to be true for pretty much everybody in the American Labor movement, but I certainly don't speak for the entire movement. I would say our union's input has been zero, none. Um, during the Biden administration, the White House was always a phone call away. Uh, we worked with, um, uh, a number of different agencies during those years. DOE, of course DOL, of course, but many of them, you know, some of the alphabet soup that you haven't necessarily heard of, and it was easy. We just went and talked to them, here's what we think, and they would take that input. I went to the White House twice between election day and inauguration day, and after inauguration day happened, that was the end. There has been zero contact since then. Now, they may be speaking to some of my brothers and sisters elsewhere in the movement. I'm not necessarily aware of everything, of course, but. It would be very limited and very niche if it was happening.

Ariana Brocious: What about the, the tariffs and the changes that have been put in, in that regard with the Trump administration? How's that affecting you all?

Lee Anderson: Yeah, so for many years, um. I always felt lucky that, that that trade policy was, um, an area that I didn't need to have an opinion about. I didn't need to think about, because domestic utilities by and large were not trade exposed. That was the something that my, my colleagues over at the steel workers or the machinists worried about, right? We did not worry about that. Um, we make electrons or drinking water or what have you here and that's it at the end, tariffs have changed everything. Um, there's a number of our employers that we work with very closely on policy and, you know, how is this gonna affect our industry? And it's, and I've seen that again and again and again over the last six months. Media tends to focus on things that are obvious, that people can understand. Like cars, cars are gonna be more expensive because of parts cross the border six times and steel is getting more expensive. And that's all easy to understand, but it's true for everything. Okay? You imagine how many parts are in a car, how many parts are in a power plant?

Ariana Brocious: A lot.

Lee Anderson: transmission line a lot, or a transmission line or, or, or pipeline or, you know, a, a wastewater treatment facility. Millions upon millions of parts. These parts are not all made in the Ohio River Valley. They are made around the world, so naturally tariffs make them all more expensive sometimes directly because it's apart being imported from here or to, to our, from that country, to this country, sometimes indirectly, because now you know, steel prices are up and that's major, it's across the board. The entire thing has become more expensive, and so naturally that will be passed on ultimately to the rate payers because that's how capitalism works. Costs are passed on to the consumers.

Ariana Brocious: So tariffs, uh, that are affecting the utility industry writ large, are gonna mean higher utility bills for you and me.

Lee Anderson: Yes. There's just no other way to parse it. I mean, that's what businesses do with their costs. They pass them on to their customers.

Ariana Brocious: Mm-hmm. So if you were able to talk to policymakers right now, what would be on your docket? You know, what would you wanna put forward, um, as recommendations that would most help your members?

Lee Anderson: Well, One of the largest ones that's the most distressing is kind of the wonkiest maybe, uh, not as obvious to folks outside the beltway, but this notion that the person in the White House, whomever that is going forward, Democrat or Republican, can unilaterally decide whether or not to actually spend the money that Congress has said, there's the money to spend. This is a new thing. And if going forward, future presidents of whatever party can say, I'm just not gonna do that. Well then we're in an entirely different country, practically. So I would say, and I have said like this has to be sorted because, I mean, it's a cliche at this point because it's true. If there's one thing that businesses loathe, it's uncertainty.

Ariana Brocious: right.

Lee Anderson: And if they are not sure that those tax credits are gonna stick, that the money's gonna be there, they're not gonna jump on it. They're just gonna sit on their hands and wait to see what happens in the next cycle.

Ariana Brocious: Well, and you aptly touched on this core concern, which is Congress has the power of the purse. Congress is supposed to have that power and, um, it's being challenged.

Lee Anderson: You know, I, you would think after 15 years in DC I would be a little bit more cynical, but I perhaps naively thought when this began six months ago, that even the Republicans would say, wait a minute, the power of the purse is ours. You don't get to decide that, you know, maybe that's a little too Schoolhouse Rock. Turns out that's not what happened at all. And so what does that mean for future administrations? I don't know. I mean, if you are in the opposition party, and you could say, now it's a Democrats, but in the future might be the Republicans, if you're in the opposition party in Congress, what incentive do you have to negotiate on a budget bill when you don't know if that is even gonna happen?

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. so we're in a very tumultuous time a lot remains to be sort of sorted out, um, you know, four years from now, 10 years from now. Do you think that the policy landscape as it applies to organize labor, we'll be able to return to where it was before this administration?

Lee Anderson: Well, let's do a thought experiment in which in 2028, we have a Democratic in the White House, a democratic control of the House and Senate, let's just imagine that happens. It could. It could

Ariana Brocious: okay.

Lee Anderson: Would, would they, would they rebuild institutions like the NLRB or U-S-A-I-D or all of the other things that we've seen dismantled? They would probably try to, um, however, I think now the right would feel empowered to fight that, that there would be no. Well, this is how it was, so we have to go back to it. They would fight it going back to what it was, I think in that scenario, the Democrats would attempt to rebuild institutions, but that will not be easy or guaranteed, and it's always, always only, only a two year election cycle away from just falling apart again.

Ariana Brocious: It's a dark place to leave it. Uh, no. I mean it's really, it feels really on point.

Lee Anderson: lemme, here's an, lemme here's this is, I know this is anecdotal, but I couldn't hardly believe it when it happened and it just illustrates so many things. Um, when it comes to policy stuff, we do often partner with some of our employers. 'cause we actually have a lot in common when it comes to policy. And we had fought long and hard for a lot of these credits and these programs to, for money to go out to, to these projects 'cause it would be jobs and et cetera. Well then they were pulling it all back and one of our employers goes to one of the key senate offices. I'll leave all the names out of this and says, Hey, you know, we had all these plans, we were gonna build all this stuff, and now you're pulling these tax credits back. What the heck? Republican senate office and the response was literally quote, well, you should have known that we weren't gonna let those stay in place. You shouldn't have made a plan based on that. Now that a Republican who – I'm so old fashioned, I remember when Republicans were the party of business and that they would expect business not to be able to rely on government policies – is beyond mind-boggling to me. Now, the, I mean, these are companies that are investing hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars into an infrastructure project. They are not going to do that, absent certainty in regulatory and and policy issues. They're just simply not going to do it. I don't know, now that it's been broken, how we repair that trust? What will it take for a large business to trust government when you're talking about investment at that scale?

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, That's actually a really useful anecdote. I appreciate you sharing it. Lee Anderson is Director of Governmental Affairs for the Utility Workers Union of America. Thanks for joining us on Climate One.

Lee Anderson: Thanks so much. Glad to be here.

Ariana Brocious: Coming up, how one pro-labor group is working to expand on climate policy wins in New York and Illinois.

Lara Skinner: We can actually support unions and union coalitions in other states to develop similar plans to win worker centered climate victories.

Ariana Brocious: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Kousha Navidar: This is Climate One. I’m Kousha Navidar.

What does a worker centered view on climate policy look like? My home state, New York, may have some answers to that question. The Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act - which became law in 2019 - set legally binding climate targets. It also explicitly included job transition training and a goal to minimize workforce disruption.

The Climate Jobs Institute at Cornell University helped bring policies like that to fruition. I had the opportunity to talk to their executive director Lara Skinner about these policy wins and how other states can push for similar changes.

The fight for these policies started when a major climate fueled disaster hit the northeast.

Lara Skinner: After Hurricane Sandy, which happened in 2012 in New York,we at Cornell started thinking about what a more worker centered climate agenda would look like. We were concerned, both with the impact that the storm had on working families. and the disproportionate impact that it had on working families, but also that, there were a lot of solar and wind projects that were being built in the state at that time that were being built, non-union, and we were concerned about the quality of those jobs, low wages. Low quality jobs. We were also seeing a bunch of plants, power plants being shut down in the state at that time. So coal plants were being shut down. The Indian Point nuclear plant was being shut down and a lot of good union jobs were being lost in those shutdowns. There was also pretty significant community. impacts, from those shutdowns as well. Coming out of Hurricane Sandy, of course, the, climate environmental movement advocates, were really thinking about what does the climate agenda look like in New York. And so we pulled together. A number of building trades and energy unions and other unions in New York and said, would you engage in a, you know, a research policy, educational process with us, to put together, sort of a job centered plan to address climate change in New York?

Kousha Navidar: Why was it important to have a worker centered view of climate?

Lara Skinner: We don't wanna see a lot of the good jobs that are currently in the energy economy lost, right? And if we're losing jobs, are we creating equivalently good jobs on the other side? So as we're investing in clean energy. Are the jobs that we're creating in solar and wind and geothermal and energy efficiency are these high quality jobs that can sustain families and communities. And from our perspective, you know, there's a climate crisis. We also have a crisis of inequality in this country, right? We have vast inequality by income, by wealth, by race, by gender. And so as we tackle climate change, we're building out a whole new economy. And so this is an opportunity to deal with some of those historic inequities. The other thing I would say is, workers in the energy sector are experts in their industry and they have a really good handle on what this transition could look like and how to make it work.

Kousha Navidar: Hmm. So right after Hurricane Sandy, we see Climate Jobs New York launch. Can you walk us through from then till now, some of the most notable ups and downs that you've seen in New York since Climate Jobs New York was launched.

Lara Skinner: Yeah. Yeah. So climate jobs in New York was launched in 2017. Um, they launched with a 10 point plan, uh, to tackle climate change and inequality in the state. The main focus of the plan was around offshore wind. and again, this was connected to, Indian Point, closing down Indian Point provided a third of New York City's power. It's hard to get power into New York City. And so there's a big question about, okay, how do we replace that power? How do we get more electricity into New York City? And also how do we create. A lot of jobs in New York state as we,build out our climate safe economy. And so the unions that were involved in the process recognized that offshore wind was a major opportunity for them, right? Like they could do the construction of offshore wind turbines, but also there's a lot of manufacturing and, you know, assembly and operations and maintenance work and offshore wind, you're talking about building a whole new industry. Um, and so they advocated for a major build out of offshore wind. They advocated for nine gigawatts of offshore wind to be built, which is is huge. and they also advocated for there to be really strong labor and equity standards on all of the projects that were built in New York. they ran a campaign and they won that. Um, so New York was the first state in the country to make, a big, bold commitment to offshore wind, which really created a lot of market certainty, for the industry, but also it was the first state in the country to have a requirement that, the jobs were built with high quality family and community sustaining jobs.

Kousha Navidar: You know, part of your work is also about educating the workforce too, about renewable energy. Can you talk about your approach there?

Lara Skinner: Yeah. So I mean a lot of what we do is study the labor and employment impacts of climate change. So a lot of folks in the environmental and climate world really look at what we need to do to reduce emissions. and that's really important. And about half of our team are climate experts. They're climate policy experts, climate scientists.but the other half of our team is labor and employment experts. And so the other part of, our job is to think about what is the job's impact of this transition? What are the labor and employment impacts of this transition? When we're connecting with workers, we're really helping them understand, okay, if this policy's passed,how is that going to affect current industries? And if this policy is passed, what new industries might we see emerge? And so really to be able to understand both the challenges around job loss. And how we might mitigate those, but also what are the opportunities, right? What are the new industries that are gonna be built and how many jobs will be created in those industry? What type of jobs are we talking about? Plumbers? Are we talking about electricians, iron workers? What sort of workforce training needs to happen to prepare, um, and make sure that we've got workers ready to do those jobs.and, you know, what are the, the opportunities gonna be for workers to, to move into those new clean energy projects?

Kousha Navidar: When you're in those conversations, are there any like themes that have emerged that have surprised you or that you find yourself reflecting about?

Lara Skinner: I would say one of the main things that has surprised me is that so many of the unions that we work with have been training their members for clean energy work for 20, 25 years. the International Brotherhood of electrical workers representing electricians. Have been training members on solar installations, on electric vehicle installations for more than 25 years. And that's like a big part of what unions do and particularly their labor management training funds, is look at where is the industry going, right? Where is the work gonna be in 10, 20, 30 years? And how do we make sure that our members are trained up to do that work? And union training centers are exceptionally good at making sure that they are training for those new technologies. the biggest challenge is that the jobs aren't there, right? So you chain somebody to do solar work, but then there's not the solar work there, right? You're not building enough projects to actually employ members in that work. And that's hard, right? Because then somebody's been excited about a new industry. They've been trained to work in a new industry, but then the projects don't materialize.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, right there. the timeline of one's career does not always align with the timeline of the industry in which they find themselves, which is true in a lot of industries.

Lara Skinner: I mean, um, a lot of workers that we talk to are very open to transitioning to new work. Um, and actually in the, in the building and construction industry, you're working project to project that is your life, that is your career, right? You're, you know, you hope you get a project that's many months or even years long, um, that employs a lot of folks.

You know, is a big project, but a lot of times it's not. Right. It may only be a few months. And so, so as workers and as unions, you're constantly looking at what are the next projects gonna be. Um, and so workers are quite familiar with that, but what they wanna know is that there's gonna be another project, right?

That there's gonna be work in the clean energy space, and that they're gonna be Equivalently good jobs, right? So you don't wanna work in the gas industry and then switch to geothermal and get paid $30 less an hour, right?

So the biggest thing is that there are equivalently good.

Careers and jobs in these new industries.and I think that's what unions have been really good at,

Kousha Navidar: So let's, let's jump ahead a little bit that that work eventually expanded to the Climate Jobs National Resource Center, which takes elements of the work you all did in New York and expands it across the country. What successes have you had

Lara Skinner: Yeah. Yeah. So after climate jobs, New York was set up and won this big victory on offshore wind. We then had, um, unions from many other states coming to us and saying like, how did you do this? Like, how does New York have a worker centered vision to take on climate change? And now is winning, these great victories that include both climate victories but also victories for workers and jobs. and so that's when,myself,Mike Fishman, the president of the Climate Jobs National Resource Center, and,a couple of other. folks who were involved in the New York work said we should have a national resource center, where we can actually support unions and union coalitions in other states to develop similar plans, and be able to do similar work and campaigning, to win,worker centered climate victories. And one of the most important, um, victories that's happened in the last few years is climate jobs Illinois was set up. So again, this is a state-based labor led coalition. They got set up and they got very engaged in the negotiations around what became the Climate and Equitable Jobs Act. And that was legislation that the environmental movement had tried to pass for many years trying to set climate targets for the state of Illinois. And frankly, you know, labor was concerned about those targets being set for a long time. But once we were able to work with the unions in Illinois and they were able to set up their coalition, they said, we can get behind this as long as workers who currently work in the energy industry are gonna be protected in this transition.as long as there are strong labor and equity standards on any new investments, right? And new work. We wanna make sure that if Illinois is building a bunch of solar and wind, that it's gonna be built with high quality union labor. And we also wanna make sure that there is money for workforce training so that folks from frontline environmental justice communities have pathways into high quality union apprenticeship programs and union careers in the clean energy industry. And so the Climate and Equitable Jobs Act was passed and it's, you know, I think one of the best pieces of legislation in the country.

Kousha Navidar: It sounds like that coalition was a pretty important step in the process. Can you tell me more about those coalitions?

Lara Skinner: Yeah, so the state-based labor led coalitions are coalitions of unions and a state that are focused on moving a strong climate and jobs and equity agenda in that state. It is typically made up of building trades and energy unions. that is where we have really sort of focused our efforts, for unions who are in the public and service sector.there tends to be a more natural affinity to work on climate issues and an easier sort of connection to that work. Obviously if you currently work in the energy sector, you're more concerned about job loss. You're worried about plants and industries being shut down, um, and there not being those equivalently good jobs. And so, when we do this work in a state, we focus on working with the unions that are at the heart of this transition, who are most concerned about job loss. and so the coalitions are typically centered around those unions, but often become much broader. and include, unions like the Service employees, international Union, the American Federation of Teachers, the National Education Association Public Sector Unions. They hire staff, and they set up a whole organization so that they have the capacity to really get engaged in climate work.

Kousha Navidar: How do you find is an effective way to expand the states in which you have coalitions to exist? Is it generally that somebody approaches you or that you look at some opportunity and do proactive work?

Lara Skinner: We are typically working in a state because someone has invited. Into the state. You know, a partner in the labor movement has invited us into a state. And, the labor movement has a really special culture,and organization in that they're very connected across states, right? There are international unions with affiliates at the local level in every single state. And so once you work in New York, it's very easy for the plumbers and pipefitters worked with us in New York and then,they're sharing that with the plumbers of pipefitters in Illinois and California. and so it's really like word of mouth, right? That folks here are like, oh, you were able to do this? maybe we should try to do that in our state.I have a lot of conversations with union leaders around the country and it is very common now that I hear folks say, the most important issue to my kids is climate change. And so many of the leaders that we work with,feel a strong responsibility and obligation to figure this out. They also feel a strong obligation and commitment and responsibility to their members, right? And making sure that they have work and making sure that they keep the good jobs that they have. And so it's been, you know, really. inspiring,and encouraging to see so many leaders coming to us and saying, we wanna figure this out. We know there's a climate crisis. We know we need to do something, but we wanna do it in a way that works for working people.

Kousha Navidar: Lara Skinner is Executive Director of Climate Jobs Institute at Cornell University. Lara, thanks for hanging out with us

Lara Skinner: Thank you so much. Thanks for having me.

Kousha Navidar: Hey everyone, it's Kousha and Arianna. It's coming up to the end of our show and that means that it's time for Climate One more thing.

Ariana Brocious: Kousha, what's your one more thing?

Kousha Navidar: Okay. So I found a wonderful guest essay in the New York Times last week, uh, about clouds, and it had a awesome graphic. Behind it, like a whole, not animated, but as you scroll, it shows you different kinds of clouds and a beautiful artistic interpretation. The essay itself is by Gavin Pretor-Pinney, who's an author, and also the founder of the Cloud Appreciation Society, which is like 20 years going. And the, the graphics are by Taylor Maggiacomo. And the gist of the article is that we kind of take cl, some of us take clouds for granted, but they have a big impact on our climate future. And they go through all the different kinds of clouds that there are and the role that some of them specifically play at cooling the earth, but those clouds specifically are starting to disappear, and how that could accelerate warming faster than we expect. So if you want a primer on clouds, different kinds and how they affect our climate, check out that essay. I enjoyed it. The title of it is We Take Clouds for Granted.

Ariana Brocious: Wow. The Cloud Appreciation Society is one I had not heard of. I'm intrigued to learn more.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, me too.

Ariana Brocious: We'll put a link in the show notes on our website and that's our show. Thanks for listening. You can see what our team is reading, articles like that, by subscribing to our newsletter. Sign up at climateone dot org.

Kousha Navidar: Climate One is a production of the Commonwealth Club. Our team includes Greg Dalton, Brad Marshland, Jenny Park, Ariana Brocious, Austin Colón, and Megan Biscieglia. Our theme music is by George Young. I’m Kousha Navidar.