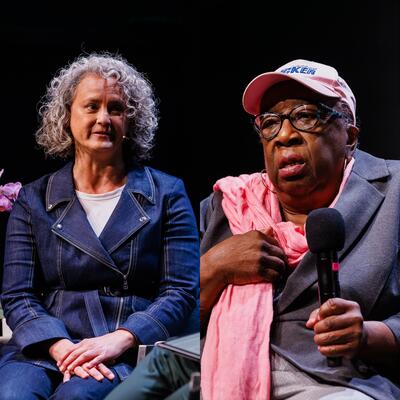

Prosperity and Paradox: A Conversation with Arlie Hochschild and Eliza Griswold

Guests

Eliza Griswold

Arlie Hochschild

Summary

Red states, blue states – when it comes to our environment, are we really two different Americas? New Yorker writer Eliza Griswold spent time in southwestern Pennsylvania to tell the story of a family living on the front lines of the fracking boom. Berkeley professor Arlie Hochschild traveled to Louisiana to escape what she calls the “bubble” of coastal thinking. Both writers emerged with books that paint an honest portrait of a misunderstood America. On today’s program, tales of the people whose lives have been impacted by America’s craving for energy, the choices they’ve made, and their fight to protect their families and their environment.

Full Transcript

Announcer: This is Climate One, changing the conversation about energy, economy and the environment.

Today, dispatches from Middle America – or as it’s known in some circles,

Eliza Griswold: “Trump country.” I think Trump country is a dangerous stupid moniker we shouldn't use anymore. It just allows us to write off wide swaths of America.

Announcer: Eliza Griswold spent time in southwestern Pennsylvania to tell the story of a family living on the front lines of the fracking boom. Berkeley professor Arlie Hochschild traveled to Louisiana hoping to escape what she calls the “bubble” of coastal thinking.

Arlie Hochschild: So let me get into a bubble that as far right as Berkeley, California is on the left and take my alarm system off.

Announcer: Both writers emerged with books that paint an honest portrait of a misunderstood America. Tales of prosperity and paradox. Up next on Climate One.

Announcer: Red states versus blues states – when it comes to protecting our environment, are we really two different Americas?

Climate One conversations – with oil companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats – are recorded before a live audience, and hosted by Greg Dalton.

When the fracking industry came to her Pennsylvania community, Stacey Haney felt good about signing over the rights to use her family farm. To Stacey, it felt patriotic.

Eliza Griswold: Her father was a Vietnam combat vet and she really wanted to keep American troops out of harm's way, out of foreign entanglements over oil. And so she thought she was really doing her duty by signing this lease.

Announcer: What happened to Stacey’s family as a result turned her world upside-down. New Yorker writer Eliza Griswold tells her story in her new book, “Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America.”

Spending time in this Appalachian community, says Griswold, opened her eyes to a side of America that many don’t know – and don’t bother to understand.

Eliza Griswold: We know what our stereotypes are and we feed them, you know, reporters go out for a day to Trump country.

Announcer: Sociologist Arlie Hochschild also wanted to get past the stereotypes. That led her to leave her “Berkeley bubble” behind to spend five years reporting on the conservative community of Bayou Corne, Louisiana.

Arlie Hochschild: When I got there, I told him hi, I’m from Berkeley, California interested in the Tea Parties. He said, “Berkeley, so y'all communist, right?”

Announcer: Hochschild’s book, “Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right,” tells the story of a community that’s been betrayed by the promise of prosperity – and by a government that has let them down. It’s what she calls “The Great Paradox.”

Arlie Hochschild: The heart of it is this question of why it would be that the states that are the most polluted are also the states with the most voters who don't believe in regulating polluters.

Announcer: On today’s program, Greg talks with Arlie Hochschild and Eliza Griswold about the people whose lives have been impacted by America’s craving for energy, the choices they’ve made, and their fight to protect their families and their environment.

Greg Dalton: So Eliza Griswold, tell us about Stacey Haney. Her dad was a Vietnam vet. She thinks that U.S. energy is better than foreign energy. Tell us about her.

Eliza Griswold: So Stacey Haney is a nurse and a single mom of two kids. And she and her family have for about the past hundred years been from two towns in Southwestern Pennsylvania just where Appalachia began. The towns are named Amity and Prosperity. And Stacey, she is truly a remarkable person she has the small farm, she’s had it for really the family has had it for about a century. It belonged to her great-grandfather.

And what happened in 2010 and 2011 is that her son who is 14 at the time, Harley, began to develop mysterious illnesses. And she as a nurse had the capacity to do some testing. And she found that she and her daughter and her son had benzene and toluene in their bodies. And Harley had arsenic poisoning. And once she got this information and she knew that there was gas drilling just next door on conventional drilling fracking about a quarter of a mile from her house. But then her daughter looked in her seventh grade computer science class, looked at their house on Google Earth and she saw that just a quarter of mile from them there was a 7 acre industrial waste pond. And it turned out that pond was not only leaking, it was off-gassing near lethal levels of hydrogen sulfide into the air. It was literally rotting with a bacterial infection. This were just the very beginning of Stacey learned about this mystery that was unfolding next to her and how it might be impacting her family’s health.

Greg Dalton: And there’s one dramatic moment where I think she's in a room with her friend Beth and some energy representatives and they're about to sign a lease.

Eliza Griswold: So, you know, when fracking came to Southwestern Pennsylvania a lot of the messaging around it and a lot of the reason that Stacey wanted to sign a lease was this idea of energy independence, which is clearly nothing new. But to Stacey it felt patriotic. And it felt patriotic for a couple of reasons. First of all she comes from the Rust Belt and the promise of industries return -- her dad was an out of work steel worker and they grew up in poverty. So the idea that she was doing something for her region so people might go back to work, that was very positive. But what was also positive you mentioned her father was a Vietnam combat vet and she really wanted to keep American troops out of harm's way, out of foreign entanglements over oil. And so she thought she was really doing her duty by signing this lease and she was also going to end up with $9,000 payment that would allow her to build her dream barn. And that was really, she thought gonna secure her spot in the middle class.

Greg Dalton: And one of the interesting points I noted was that coal and oil have been extracted in these areas, and most of the money left. But with fracking, some of the money stayed because people were able to lease for frackings like hey we can get rich, you know, the money can stay here in a way that it didn't for coal and oil.

Eliza Griswold: Absolutely. So this is one of the most important points that we really need to understand. When outsiders come into this place and they say how can you possibly be signing leases, you know, many of the people who live in this part of Appalachia have extremely sophisticated understandings of the minerals underneath their property. And, you know, for coal in particular, coal has been divorced; they haven't made any money off of coal since the late 1800s. And so Stacey in particular in fact the kind of coal mining that's going on in this area that really undermine, that's the verb, undermine the town of Prosperity next door is something called longwall mining. And when the longwall industrial mine comes under your house, you by definition lose your water for your farm. So people were afraid and they are still afraid of what’s gonna happen when the longwall comes. And so for Stacey and her neighbors signing these gas leases they thought might actually be a protection against coal. And that’s a story we don't hear very much at a distance on the coast. And we really have to understand the complexity of why people made these decisions because they’re not simply voting against their own interests.

Greg Dalton: Arlie Hochschild, one of the characters in your book is Lee Sherman sort of epitomizes the Great Paradox. So tell us about Lee Sherman and the Great Paradox.

Arlie Hochschild: Well, Lee Sherman worked all his life for petrochemical companies. He was a pipe fitter. And he worked for Pittsburgh Plate and Glass. And one day he was asked by his boss to take on a certain mission and it would be at dusk when nobody could see. And there was something called a tar buggy and it was heated from the bottom and it had all the toxic waste and sludge that had produced that day. And it was Lee's job to look left, look right make sure no one was seeing and unscrew a valve and release this toxic waste into public waters.

And he told me this, he is now in his 80s, and he told me that he was felt guilty about doing this. But one thing happened that on the job he himself was exposed to ethylene dichloride and he got sick, couldn’t move his legs. So he was put on medical leave by the company doctor and later he was fired for absenteeism.

So here's a man who'd been doing the dirty work for the company who himself was now out of a job and out of health and he became an environmentalist later in life and also enthusiastic voter for Donald Trump. And I had periodic conversations with him about how he puts these two things together. But he regrets what he did and he’s --

Eliza Griswold: I think of all the characters and the stories in your remarkable book, Arlie, it’s Lee Sherman who is just indelible. And the complexity of that moral situation that I just can’t get out of my head.

Greg Dalton: Another character in Strangers in Their Own Land is Mike Schaff, a lifelong resident of the Louisiana bayou about an hour south of Baton Rouge. He’s tea party member, a Trump supporter and an avid fisherman. In 2012 a giant sinkhole swallowed much of his small community because of a well drilled by a salt mining company called Texas Brine. The well punctured a naturally occurring salt dome underneath the ground. Schaff campaigned for years to get compensation for displaced residents.

Arlie Hochschild: Right.

Mike Schaff: Well I’ve been a conservationist since I’ve been a little boy. Since I’ve been fishing and hunting and stuff and I’d find dead fish and I knew something was wrong. I joined the green army which is a sort of a coalition of people on Louisiana who got screwed by companies, you know, and we fight each other’s fight and support them. And I am pro-industry, I’m just pro-clean industry, you know what I mean. We need what the industries, petrochemical industries in particular in what they produce. Our goal is to make it be produced in the most environmentally acceptable way as possible. I mean who wants a dirty water or a dirty atmosphere. Do you know of anybody that wants that? How many Republican friends you got, do they want that? Well, they don’t want it I promise you. We have some air pollution problems mainly because of the state agencies that are in charge of it are under the thumb of the legislatures and the lobbyists and industry. One person asked me why I vote for Trump when he’s getting rid of the EPA. And I asked them what has the EPA done for me? We’ve asked them to intervene on this mess we have over here and they haven’t lifted a finger.

Greg Dalton: That’s Mike Schaff, a Trump supporter outside Baton Rouge. Arlie Hochschild, your response to what he said there.

Arlie Hochschild: Yeah. You know when I first met Mike and I asked him why was he like the tea party and why government, big bad federal government or state government was so bad. And he said, well, I believe in community and the government is doing for us things we ought to do for each other for community. So get rid of government, recover community. And yet what happened to him with about the Bayou Corne Sinkhole was that he lost a community, his whole community was declared a disaster zone, a sacrifice zone. But it wasn’t big bad government that took it away it was unregulated industry that took it away in the absence of good government that took it away.

I went to visit him in Bayou Corne. And he just shortly after this had happened and things were -- it never had earthquakes before, but suddenly there were earthquakes. And he thought he was having a heart attack because things were moving and it sounded like someone had put a dumpster just loud. And then he began it was raining and he noticed there was bubbling in his front lawn it was like Alka-Seltzer that was methane gas that was there.

Everyone else had left but he didn't want to leave that's how much he loved his community kind of a Cajun community many people had been working in the oil industries and were retiring there loved this community and he didn’t want to leave it. But he had this gas monitor he’d check it in the middle of the night. You know if you lit a match, the place could go up but he took that risk, that’s how much he love this place and how much he hated leaving it.

Eliza Griswold: I think just to talk about regulation a little bit like to tease that out a little bit. Why do people feel that the federal government is against them like what is their lived experience of that. When you look at farming communities where there are small farms like if you look at Appalachia in this area of Southwestern Pennsylvania, there's a pork farmer who comes to mind, a guy named Jason Clark, he’s president of the Washington County Pork Association, he’s in his 30s and he has a brother who is an opioid addict. And because when I talked to him about let's talk about the government why are you so opposed to regulation and he tells this story which is, you know, he’s got the small number of pigs every time has to give a pig a shot he’s got to pay a hundred dollars because according to regulation the vet has to come out and give that pig the shot. But if he just thinks maybe his shoulder hurts a little bit he can get in his car drive 10 miles up the road go to MedExpress and get a prescription for oxy. And he turned to me and said, you wanna tell me the government isn't hypocritical, I am less regulated than my pigs are. So just to understand that a little bit that is lived experience for people in a great deal of America.

Arlie Hochschild: Right. I really think that’s a great comment. And I would add that in the case of Louisiana, it’s interesting that in a way companies give to the state the moral dirty work of promising to protect them from pollution, but not protecting them from it.

In the case of Louisiana there was $1.6 billion that was given to a variety of industries as incentive money to come and basically process the natural gas they weren’t getting from Pennsylvania. And so with that money companies could give out money for the Audubon Society and chemistry classes for the third grade and LSU uniforms, you know, so they could branding, they could be thought well of. But it's also true that the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, they don’t even have protection in the name, does not protect people, they, as Mike himself said at one meeting, oh they give out permits like candy. So in a way everybody thinks well, industry is okay but it is government whose salaries you're paying for environmental employees are not protecting you. So it's easy to explain why they think state government what are these people doing, they’re not doing their job.

Announcer: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about prosperity and paradox in Middle America. Coming up, how oil fracking on her land further impacted the lives of Stacy and her family:

Eliza Griswold: She loses her house, she loses her way of life - she's living in a trailer with her kids…They really are a different kind of climate refugee.

Announcer: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Announcer: We continue now with Climate One. Greg Dalton is talking about Americans living on the front lines of fossil fuel extraction. His guests are Arlie Hochschild, author of “Strangers in Their Own Land,” and Eliza Griswold, author of “Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America.”

Let’s continue with the story of Stacey Haney, whose family began to get sick after gas drilling contaminated their farm in southwestern Pennsylvania.

Greg Dalton: And in the case of Stacey Haney she went through a lot of work to try to understand what's in her water to get her water tested.

Eliza Griswold: Sure. I mean, so in Pennsylvania the Department of Environmental Protection is often called “don't expect protection” that's its acronym for local people. The way that it works and NPR state impact in Pennsylvania has done excellent work on this issue. There's a revolving door between public-service and private industry. And that is really important to understand because it's a form of public poverty that's really driving a lot of the lack of regulation and the lack of upholding state regulation.

So what Stacey did is she tried time and again to hold different parties accountable to testing what was in her water. Essentially what happened is that the state DEP was coming out to test, if you complain that your water is contaminated by oil and gas you suspected it, the state DEP would come out and they would test for 24 different metals associated with oil and gas contamination. But when they got those results back so they were testing for 24, but they would only give you results for eight, right. And that is exactly how these kind of, this is how this unfolds, right, that people have inadequate information that leads them into great harm.

Greg Dalton: And there’s even one scene where she meets with regulators and she get some information and then one of the regulators calls her back afterwards and says “don't drink your water” and like hangs up.

Eliza Griswold: That’s the EPA. So the EPA has launched two criminal investigations into the site. And I am proud to say that since the book has come out, Josh Shapiro, the Atty. Gen. has launched a new investigation.

So I was at, you know, I’ve been going around talking about this book and I was in Washington DC not long ago and most of my work as a journalist has been in Afghanistan and elsewhere. And there was a guy in the front row who was bald and I was sure he was like a tough general I forgot, from Afghanistan and he came striding up to me after the reading, I thought oh god I don’t remember this is. And he said, you know, I am Marty, I'm the first state federal regulator on Stacey's case and I did everything I could to make those that stick and I couldn't do it, right.

So you look at the failure and I’ll just say this that, you know, some of the people in the book were standing by this contaminated site when a state representative somebody from the DEP asked a representative from the private company if there were jobs available at the company. I mean but and why shouldn’t they because they need to feed their families too. So these are the complexities and the ways that we have to really understand how people live their lives and how we have to do better at addressing public failure.

Greg Dalton: So eventually she does get some of the information, Stacey get some information, she has to leave her land.

Eliza Griswold: Yeah. So Stacey has to leave her land, I mean following this in real time was mind-bending. Because, you know, when I first met Stacey, I met her at the Morgantown West Virginia airport the first time she ever spoke publicly about what she feared was happening. And she didn’t have much information and she was terrified that if she spoke out publicly the company that was supplying her water at that time would punish her by taking the water away. And she does not, she’s not a fan of journalism she’s not a fan of outsiders. She wanted the company to do right. And she believed if she told them her story that they would do right by her. And time and again this fails over seven years.

So finally, what happens is her kids are so sick they have to move out, they move into a trailer behind her parent’s house in the nearby town of Amity. So she's living in a trailer with her kids at night it’s so cold that they tried not to roll over because they stick to the trailer’s walls because they are warm and the trailer is cold. She's constantly on the move. They really are a different kind of climate refugee. You know they are really moving as a result of extraction next door to their house and they lose in the process the way that she and her neighbor Beth Voyles start to put together what's happening is the death of their animals. They keep losing goats and dogs and horses. And it’s that kind of sensitivity to toxicity that makes them put the story together.

So they lose everything. She loses a house she loses a way of life. She loses her farm. She loses all of her animals because when the house is abandoned wild dogs end up attacking the farm. And that was just, I mean it was really apocalyptic and as much as the story is about fracking it’s really much more a story of the failure of the common good and what it is that binds us together.

Eliza Griswold: Eventually the company settles. And I don't know what those terms are because they are protected under the terms of the settlement which is quite standard.

Greg Dalton: How do they feel about the settlement?

Eliza Griswold: They feel pretty disappointed. I will tell you they feel pretty disappointed. And Harley, you know, in the course of the book we meet this 14-year-old boy who wants to be the first kid in his family to go to college. He wants to be a veterinarian. He loves animals. The process of seeing animals sick and then die makes him think I'm not gonna be a vet. Then he wants to go into the military like his grandfather. And then he decides that he is not gonna fight for a country that has let him down that has failed him and his health isn't good enough either. He runs a lawn company and finally he does what he is doing today; he goes to work for the pipeline. He's laying natural gas pipe for the industry that's sickened him. So it's hard to imagine what this industry has cost this family.

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining us at Climate One my guests are Eliza Griswold, the journalist at The New Yorker and fellow at Harvard Divinity School. And Arlie Hochschild is an author and a professor of sociology at University of California Berkeley. I'm Greg Dalton. Arlie, I want to talk to you about the empathy wall the empathy gap because you -- why would anyone in Louisiana talk to a liberal from Berkeley first of all? And how did empathy play into that?

Arlie Hochschild: Yeah. Well, five years ago I decided that already the country was splitting in half and Congress was at a gridlock and Trump was not yet in the White House. But I thought I don't know anybody on the other side not really to talk to in a complex way. So and they probably don't know me in fact, we're all in bubbles, electronic bubbles, media bubbles, geographic bubbles as we know. So let me get into a bubble that as far right as Berkeley, California is on the left and take my alarm system off. Not forever, but long enough to permit myself a great deal of curiosity and interest in the lives of people that I knew I disagreed with. And people have said, oh well, you know, you must have a lot of empathy. No more than anybody else there’s no magic to this. We do it with our children with our loved ones with our family and our friends but we just don't do it for people that we think of as really disagreeing on climate or politics or anything else. So when I went there this Mike Schaff, I told him hi, I’m from Berkeley, California interested at the tea parties. He said, Berkeley, so y'all communist, right?

And then he laughed, you know, and then I felt we can talk. He was very generous hearted and very open. He knew we didn't agree on almost anything but I asked, could I see where you were born, could I see where your school was, you know, what church did you go to, where are your folks buried. And in the course of all of this and going out fishing he knew the faces of fifty kinds of fish that oh for me there was just one category of fish but for him, this one had whiskers and that one had eyes -- he really generously shared his life with me so that I could kind of try and understand how he saw this disaster that happened to him at Bayou Corne and how he saw Trump and how he saw the EPA.

Greg Dalton: How about you Eliza, did writing this book, you know, put another narrative in your head that you can relate to?

Eliza Griswold: A hundred percent. But it’s more, yes, what’s really changed for me since the election as a journalist is, you know, my understanding before the election was really that, you know, as I mentioned I have spent until this project, most of my work has not been in the United States. And so I would write about, you know, a Syrian refugee family that was stuck in, you know, different continents because I knew that by writing about that family I would bring some pressure on the U.S. immigration system. The State Department would respond they’d have to unify the family it might help give the Obama administration some cover under which to meet quotas for refugees. I mean that was the idea, right, behind the work, okay. But I took for granted the issue of audience; that the people reading it would feel as I did.

And I think what I’ve learned is just how little our coastal readers know, you know, and how much we assume by virtue of economic privilege that we know better than others do about the terms of their own lives. And so to sit down with farmers who can tell you the history of the shale beneath their feet the coal when these things were sold off what their sophisticated understanding is, how resource extraction is a give-and-take how rural Americans have paid for the energy appetites for urban Americans for a century, that is humbling in a whole different way.

Greg Dalton: You’ve written about Veronica Coptis, I think who is a rural Pennsylvanian she carries a Russian pistol she's very much a make America great again country. And she's thinking about Appalachia after coal trying to look for --

Eliza Griswold: Yeah, so Roni Coptis who I spoke to this morning she is definitely talking about what you do in a region after coal. And there’s -- how can I say this; there are ideas that look like a great idea to us from a distance about tech that don't really play out as well on the ground as they might.

Greg Dalton: So the idea that a coal miner is gonna build windmills and have a --

Eliza Griswold: That's not universally true. There's coding going on.

Arlie Hochschild: There’s coding, yup.

Eliza Griswold: There are definitely small-scale solutions. One of my friends and I have both worked on this issue of Amazon warehouses, right. And in Pennsylvania these guys really want Amazon processing centers and of course those are going to be out of use in five years they'll all be automated, right. And my assumption at a distance would be like, oh, Southwestern Pennsylvania doesn't understand how quickly automation is coming to Amazon. No, no, they say who are you to take jobs for five years from us? At least it’s five years.

And this is true when I written about Roni, I’ve spent a lot of time with coal miners too. Young miners who are making, you know, $150,000 a year in places where the median income is $40,000. Their understanding is that coal is gonna go away, for sure the reserves are such they’ll maybe work for 10 more years. But they voted for Trump because four more years means sending their kids to private school for four years. It means paying off their house and it means paying off their car. They’re not looking toward a future; for them this political divide isn’t intractable and ideology it’s very real. It's very much a day-to-day economic reality.

Greg Dalton: Arlie Hochschild, you also write about fossil fuel executives and workers having different attitudes toward climate change. I thought that was really interesting.

Arlie Hochschild: Yeah, you know, in the back of my head I’ve and probably it’s the same for you and Eliza, of how could we get a conversation going left and right on climate change. And actually my son, David, who is a member of the California Energy Commission in charge of renewables and who is a big advocate for getting California to 100% reliance on renewables. He came with me to visit Mike last year and we went fishing and we had a conversation. And I said look, I'm just gonna hold a tape recorder here can you guys come to some agreement on how to get a clean energy, clean environment. I know you both value it, but how do we get there? What’s the role of government in it?

And that -- so they agreed that renewables are great thing and Mike had a different vocabulary for it. Yes, private enterprise you start your own business. You’re self-sufficient in energy and wasn’t that a great thing. And there actually is an organization called the green tea movement which is tea parties for green. So he was not alone, Mike, in that attitude when it came to climate change. And David was saying, well, you know, you could have solar on the roof of your house, right here in the new house he lives in and to move out of Bayou Corne, so this one’s on Lake Verret. And he said, yes, it’d be a good thing and it would even help with climate change. And Mike said, oh no, no, no, no, not climate change.

And in my mind I’ve been continuing that conversation. Mike loves the military and he said, you know I would give my life for my country. I was in the military and proud of it. The military has been a leader in renewable energy and they’re worried about rising tides that's a security issue. And actually the Navy has a higher goal than the state of California they want to get 50% reliant on renewables by 2020 and California is 25. So actually that would be a way to begin a conversation left and right. Look, for the military it's been a leader in the very thing you’re suspicious of. Also I would add that many of the CEOs for the big companies, Phillips 66, Shell, they believe in climate change. If you look at their websites, they’ll say, yeah, the science is there and it’s a problem we’re worried but the people that work for those companies don't. So that would be another way of starting with the figures that people on the right revere and saying, well look, some of them agree that climate it's real and it’s based on science. I’m not sure how much the Navy says about that but we do know that they’re worried about rising tides.

Greg Dalton: There’s a whole school that you can talk, solve climate change without using the word and talk about technology and food and sex and fun and all sorts of things just don't use that word. But Arlie, you also have the idea of, you know, exchange programs rather than college students going to France they should go to Louisiana and learn and we don't have those shuffling mechanisms that we used to have.

Arlie Hochschild: Exactly. We used to have a robust labor union movement that got people of different regions together and races. And we used to have, you know, a compulsory draft that put people together. Now we need a new one that mixes and matches us across region and class because if you look at left and right they have become region class votes.

So how do we do that? I think in high school would be a wonderful time for the south to go north the north to go south, coast to go inland, inland to go coast for three weeks work on a project together. And before you do take a class in civics and take another class in mediation. How do you listen to another how do you respect both respect and disagree with a person. Get them train to do that get each other's deep stories and maybe we could reknit this country together.

Eliza Griswold: I think that's a terrific idea. And as a journalist I think we have to do better at being careful with our work to look at who is actually in places. I mean, you know, we look at Appalachia 700,000 square miles, 25 million people and we know what our stereotypes are and we feed them, you know, reporters go out for a day to Trump country. I think Trump country is a dangerous stupid moniker we shouldn't use anymore. It just allows us to write off wide swaths of America. I was in Charleston, West Virginia a couple of days ago with some young trans activists and resistance activists they were doing different work. And they were just so eager -- what we think of who is in places, yes an exchange and also media do a better job at not going out and looking for your stereotypes because, you know, they don't want to be. They’re like we are as diverse and as boring and as screwed up as any other area of America. But don't blame Trump on us; blame Trump on the Philadelphia suburbs! You brought us Trump, you know. So I just think we have to do a better job. And that’s a lot of economics I mean it’s one thing to spend four hours in Taylor bookshop but you got to spend four days, you got to spend four years and that’s a harder ask.

Greg Dalton: And one of the things I think is the themes in both of your books is how people can smell that condescension that, you know, peel back these layers of politics, economics is that they know that the coastal elites look down on them and they resent it and they can smell it a mile away.

Arlie Hochschild: That’s right. That’s right.

Eliza Griswold: They know that the coastal elites have benefited from their poverty.

Greg Dalton: And their energy.

Eliza Griswold: And their energy. So screw like screw what somebody thinks of them like what have they actually taken from them. And I think that for me, you know, one of the things I've been thinking about bringing young people young immigrants back to communities in Appalachia. And I was working with some kids to do this and the Appalachian kids said, you can’t do that yet with people who are so you could definitely do an exchange program working on a project together. But don’t bring us people who are really very different because we are wounded and first you need to come to listen to us. And I think that degree of wound is really alien to us and I also wanna be very careful about talking about they in a general way because that’s the problem. But the individual stories told carefully with the diversity an eye toward diversity that we know is out there it is part of what I as a journalist have to be doing.

Announcer: You're listening to a Climate One conversation about bridging the empathy gap between red states and blue states. Coming up, using patriotism to fight big oil in the courts.

Eliza Griswold: They know they’re gonna face a conservative Republican bench at the State Supreme Court level and they know that the argument that's going to work is what are our God-given rights. And in Pennsylvania, one of the rights in the Constitution is the right to clean air and pure water.

Announcer: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Announcer: You’re listening to Climate One. Greg Dalton is talking with UC Berkeley professor Arlie Hochschild and New Yorker writer Eliza Griswold. They both have new books out that explore the delicate balance between conservative values and environmental stewardship.

Let’s get back to their conversation.

Greg Dalton: Eliza Griswold, a lot of the story you chronicle happens under the Obama administration. So what's your take looking back at the Obama administration how, you know, U.S. went from an importer to an exporter during that administration. So what’s your assessment of how that government did?

Eliza Griswold: That the concept of bridge fuel that was the cornerstone of Obama's policy was a farce. Unfortunately I think it was incredibly short sighted. We didn't need that bridge. That was a bridge to nowhere. I mean renewables, you know, we were talking a little bit before; the most craven energy investors who are just don't care about the environment who are just looking to make money will tell you that growth in the market is in renewables. That has lots of reasons we've reached what's called peak grid which I’m not gonna get into I'm sure that’s something you have discussed here before. So growth is off grid it’s in renewables as well as the fact that these things are easier to build and much cheaper than anybody thought. So the idea - so we don't need natural gas as a bridge fuel; we are ready for renewables. And I think that was unfortunately I don't know the genesis of that in the Obama administration certainly the idea of energy independence and national security are valuable goals and important, right and so are jobs in the Rust Belt, all of these ideas. But I have to think that industry got into Obama's ear in an unfortunate way and he believed metrics that turn out to be shortsighted.

Greg Dalton: Well there is also the electoral map that every president pays attention to and there's a lot of red states that are very important to get reelected. And those states wanted to have some kind of extraction he was trying to, you know, the Jerry Brown thing, you paddle to the right you paddle to the left and you --

Eliza Griswold: But it’s not so much the states that wanted the extraction it’s the industry that wanted the extraction. And when you look at what drives fracking and you’re gonna have Bethany McLean who is another hero here just wrote an amazing book called Saudi America, Wall Street her question is would fracking exist without Wall Street and the answer she reaches is no. Because actually fracking isn't turning a profit. What comes out of fracking the money is basically investment money. She’ll tell you much better than I can summarize her amazing work.

But again talking systemically talking about our responsibility in New York City to those who live in Pennsylvania the money is coming from Wall Street. So the reality --

Greg Dalton: It’s coming from the pension plans of people sitting in this room and listening to this podcast.

Eliza Griswold: Exactly. Exactly. So when I asked Bethany is this a Ponzi scheme? She said it's an unintentional Ponzi scheme as most Ponzi schemes are, which again she's amazing, listen to her yourself. But we have culpability here it's not just distant Texas execs or red state people voting for energy, no, it’s Wall Street.

Greg Dalton: And Wall Street is 401(k) plans and retirement plans.

Eliza Griswold: Exactly once again this is pension funds that are looking for return and are getting, and private equity but pension funds in particular that are getting deeper and deeper into this idea of energy, that in a way they don’t need to be.

Arlie Hochschild: So this suggests another form of activism, you know. Look at these pension plans and if you have a piece of one, you know, you can get together with others to get a voice and say no don’t invest in that.

Greg Dalton: And that is happening, the divestment movement on college campuses. You know there’s the Divest-Invest and there’s a lot of money is moving toward away from fossil fuel because of stranded assets all sorts of reasons. But Arlie Hochschild, you talk about how some of the dirtiest states are the reddest states. Tell us that correlation.

Arlie Hochschild: Yes. Actually, you know, it’s a part of a whole red state paradox actually. How come across the country the red states are the states that have most poverty, you know, most disrupted families, have the lowest life expectancy as part of that the worst pollution.

Plus they are also the states that don't believe in government solutions so that seems like paradox.

But the heart of it is this question of why it would be that the states that are the most polluted are also the states with the most voters who don't believe in regulating polluters. That’s kind of heart of this paradox. And actually for Strangers in Their Own Land, I did a special analysis putting together two things. There's something the EPA has a tox map and it has a measure RSEI, it's called, that looks at the distribution of the amount and volume of polluting materials the toxicity of them and the populations that are exposed to this. That’s a measure the EPA has and I hope that with these cuts that kind of knowledge doesn't go away. I related that to, it’s called the General Social Survey with a bunch of attitudes nationwide on the environment. And lo and behold the closer you are to a ZIP Code that has high rate of exposure to toxic waste, the more likely you are to be Republican, the more likely you are to agree with such a statement as the government is already doing enough to preserve the environment.

So, you know, we were talking before that in 1988 the environment didn't used to be a partisan issue. You had just as many Republicans as Democrats worried about it. Now we’re doing the splits and so now is the time for us to get together with the skeptics and sit down to see if we can find common ground.

Greg Dalton: You say skeptics that imply sort of conversion. I wanna talk a little bit the idea that people need to be converted to the way we see it. If those people would just think like me, everything would be fine. Is that the way that, you know, that's not finding common grounds, it just like I wanna persuade you I wanna convince you isn’t that where a lot of our political dialogue is right now?

Arlie Hochschild: In writing Strangers, I met an extraordinary person. His name was General Russell Honoré. And he was a rescuer in 2005 of the victims of Katrina and he now has become an ardent environmentalist. He’s leading the environmental movement and the green army that Mike Schaff is part of. And I watched how he talked to non-environmentalists and he did it this way. Not by arrogantly kind of disregarding the values and symbols of the people he is talking to but by acknowledging them and doing what I would call a symbol stretch. I’ll give you an example.

He was talking to a group of Lake Charles’ businessmen whose mantra was freedom, freedom. They didn't want anything to do with environmental regulations. So freedom to invest your money. Freedom to make a lot of money. Freedom from onerous regulations. Freedom. And so he is talking to them. They don't like environmentalists, don’t even like the word. And he says this, I woke up this morning and I looked out at Lake Charles, I saw a man in a boat and that man had his fishing line out. But that man is not free to lift up an uncontaminated fish.

I thought, you genius. Oh, I followed him around for the next day, you know, just how do we do that. We need to do that with patriotism, not to say oh you’re silly to be patriotic. No, of course not. We’re patriotic too but what does patriotism mean. Doesn't it mean a free press, doesn't it mean an independent judiciary, doesn't it mean democracy. I mean you start with the symbol and you apply it more broadly.

Eliza Griswold: I think that's brilliant. I also think, you know, that one of the ways to do this is through a conversation about rights. In the book these two heroic husband-and-wife lawyers who are no environmentalists, I mean Kendra and John Smith. Kendra is a corporate defense attorney for railroads. She mostly deals with asbestos cases. And they take a case that defends Stacey and others against the companies and against the Pennsylvania against the government itself all the way up to the State Supreme Court. And they're trying, what their argument is they know they’re gonna face a conservative Republican bench at the State Supreme Court level and they know that the argument that's going to work is what are our God-given rights. Right, these are all inalienable rights and in Pennsylvania, one of the rights in the Constitution is the right to clean air and pure water.

And that has been on the books since the 70s, but it's largely been instrumental. I mean it’s largely been decorative it hasn't had any teeth. And because of the Smiths’ case and their apt argument about our right to clean air and pure water the conservative Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court found in their favor. And that’s the kind of thinking, these are just terms to change, you know, there was something else that was so important about that.

Greg Dalton: George Lakoff is a Berkeley linguist who also says that purity is a key to unlocking to finding common ground using that right, that conservative frame.

Eliza Griswold: So as Mike said is the idea of conservation. Prudent use of resources for the next generation is a much better thing than liberal -- also I wanted to say this. Here is something you might not think about for people who are living in rural places who hold conservative values. For people who live in cities to come out to them and tell them about the environment they’re just gonna flip you the bird because oh you are so divorced from the land you care so much about the land that you live in New York City, what a joke. That’s their understanding and just I mean another way to just flip the script and see that for a second that’s the understanding.

Greg Dalton: I wanna talk about faith, you know, the way that religion plays into this. Eliza Griswold, you've written about this, you know, what role does religion play in these attitudes?

Eliza Griswold: Religion provides us another excellent word and another excellent concept to use with people who feel differently, which is stewardship. You wanna talk to conservative evangelical Christians about climate change in the environment, you talk about stewardship of the earth. And there are plenty of people I mean the issue of the environment within the evangelical community is so profound that there's a schism within the -- we are seeing it within the religious right within traditionally what we would see as the religious right. We are seeing deep divides over issues of the environment of issues of immigration of issues of abortion. And so there are plenty of people and I would call them heroes. They are really trying to move away from the cultural inheritance of religion.

And in this case that would be associated with like the Moral Majority, right 70s, 80s, you know, Christian right and return evangelicalism in particular to its roots in antislavery, its roots in Jesus' actions and Jesus' life, and there's plenty of language and shared experience there to change the terms of the conversation. I think religion has a real role to play here it’s actually something I'm just starting to work on. So I'm just starting to identify some of these figures. But again you wanna be really careful that you’re not just talking to people who are talking down to others.

Announcer: That was Eliza Griswold, New Yorker writer and author of “Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America.” Greg Dalton’s other guest on today’s program was Arlie Hochschild, author of “Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right.”

To hear all our Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast at our website: climateone.org, where you’ll also find photos, video clips and more. And join us next time for another conversation about America’s energy, economy, and environment.

Greg Dalton: Climate One is a special project of The Commonwealth Club of California. Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. The audio engineers are Mark Kirchner and Justin Norton. Anny Celsi and Devon Strolovitch edit the show. The Commonwealth Club CEO is Dr. Gloria Duffy.

Climate One is presented in association with KQED Public Radio.