Voices of the Wild

Guests

Bernie Krause

Jason Mark

Tanya Peterson

Summary

Thanks to climate change, the wild corners of the planet are shrinking or disappearing altogether. How can we preserve the natural world and its creatures?

Jason Mark, Editor, Earth Island Journal; Author, Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man (Island Press, 2015)

Tanya Peterson, Director, San Francisco Zoo

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: Let’s get out into the wilderness, wherever that is. I’m Greg Dalton and today on Climate One we’ll explore nature in the age of human-caused climate disruption. Burning fossil fuels has changed the basic biochemistry of the earth on a scale unimaginable a few decades ago. Heat trapping pollution is changing the weather, the seasons, the oceans, even where birds and animals live. It’s changing everything. I’ve traveled to Siberia in the Arctic Circle and our guests today have trekked to other regions remote around the world. How is climate disruption changing our relationship with nature and nature itself? What role do zoos and parks play in a world where air travel makes climate change worse? Over the next hour we will talk about the natural world and listen to some sounds of nature before and after humans stomped on it. Joining our live audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco we’re pleased to have three guests. Bernie Krause is a soundscape artist and author of the new book Voices of the Wild: Animal Songs, Human Din, and the Call to Save Natural Soundscapes. Jason Mark is editor of Earth Island Journal and author of the new book Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man. And Tanya Peterson is the director of the San Francisco zoo. Please welcome them to Climate One.

[Applause]

So Jason Mark, does wilderness still exists in the Anthropocene, the age of human disrupted climate?

Jason Mark: It does. I’m happy to report that it does. For the book, for Satellites in the High Country, I traveled, every good nonfiction book starts with a question and mine is, is there anything that’s still really truly wild in this human age with 7 billion people on the planet, with global climate change, with Amazon drones and Google GPS and Google Earth? And what I found is that there is quite a bit of wildness and wilderness out there in America and around the world as long as you understand that wildness doesn't mean and wilderness doesn’t mean pristine. We live in a post pristine age, there's really no place that's been untouched in the human insignias everywhere. But if you understand wilderness to mean places that are undominated by human will and undominated by civilization, places that are still self-willed then, yeah, I’m happy to report that there's a lot of wilderness still out there and I think you can continue to serve as a touchstone for our relationship with the rest of nature.

Greg Dalton: And we’re putting aside more marine reserves and wild places as we go along. Bernie Krause, you spend a lot of time out in nature sitting, listening while Jane Goodall has been kind of observing primates, tell us how you got into it and what a soundscape artist is.

Bernie Krause: Well, my background is in music and at one point I just quit and in the late 70s I went back to school, got my Ph.D. in bioacoustics because I wanted work outside, I wanted to be close to the natural world. And I just found that this was one of the most rewarding things I could've possibly done as far as life’s choice was concerned. And so here I am, I find myself recording animals for a living.

Greg Dalton: And so you go out there in nature, you got your headphones and you sit there for a very long time with a big microphone and just kind of sit there?

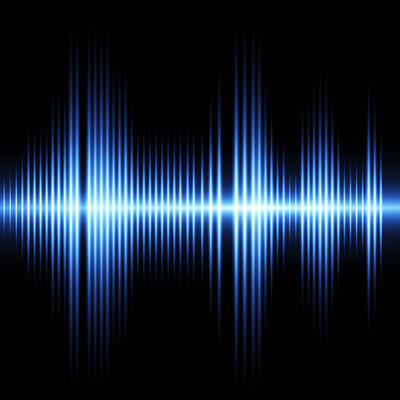

Bernie Krause: Capture the soundscapes. Because the soundscapes they give us a sense of place and they have a lot of information in them. This is the voice of the natural world and mostly we've been looking at the natural world and trying to observe it from what we see. But the natural world has a voice and I wanted to give that voice to as many people as possible through these recordings and make it possible for them to hear what beauty is out there and what resonance is out there and how much information is out there. Because it really informs us about how we’re doing in relationship to the natural world. It's telling us, it's giving us all that information.

Greg Dalton: And we’ll hear some of that. A lot of people do think of looking at nature, not so much about hearing nature. Tanya Peterson when you designed the San Francisco zoo do you think mostly about looking, do you think about the ears?

Tanya Peterson: We think about sound as well. We try to make the zoo accessible to all. Recently we've reached out to the blind community as well as with a lot of braille and touch so that those with disabilities can also hear and touch animals and wildlife as much is possible. But my joy being there on a daily basis are the animals in the morning. And you can spend the night at the zoo and if you're brave, my family did, and you hear the animals all night, you know most animals are nocturnal. My husband didn’t get a good night’s sleep tonight but it was a great experience.

Greg Dalton: It’s a fun thing to do with the kids. I never actually did it but I know it’s a fun thing to do with kids. Tanya Peterson, how is climate change changing the role of zoos?

Tanya Peterson: I think it's stressing the importance. We view ourselves as sanctuaries, the Noah's Arks of the species, if you will. All of the animals now at the zoo are either endangered, threatened or rescued, you know, abandoned situations. And our hope is one day we can return some of the species to the wild. But we’re very careful now about the species we provide shelter to, hoping that like the rhinoceros or others, that we can return the species back to a safe, if not pristine, wild.

Greg Dalton: Bernie Krause, animals in captivity is that a bad thing or a good thing?

Bernie Krause: It's a real thing and it's very much a part of our culture. It goes back thousands of years in terms of how we’ve managed the natural world. And I think that it's one of those issues that we have to discuss in the culture and see what it brings to us. I think it’s sometimes really important. Ms. Tanya was talking about it, it's an ark, it's a place where a lot of animals can be rehabilitated that has been treated not well.

Whether or not they can be reintroduced into the wild is another issue altogether because first of all you have to have some place to put them. The place has to be secure and safe. If you reintroduce a rhino in Zimbabwe or Mozambique right now its chances of surviving longer than a week or two are not great. So we have to find ways of dealing with that issue as well.

Greg Dalton: And so I want to go to some of the soundscapes, and we have a couple of clips from Bernie Krause's work. So the first one I want to cue up, Bernie, tell us what we’re going to hear about Lincoln Meadow.

Bernie Krause: Lincoln Meadow. I’ve been recording at Lincoln Meadow for many years and in 1988 a logging company came through and tried to convince the local population that there'd be no environmental impact from selective logging, a new thing they were trying to do. And so I asked them if I could record, they allowed me to record and this first recording is before selective logging.

Greg Dalton: Okay, let’s hear Lincoln Meadow.

[Recording played]

Okay, now let’s hear Lincoln Meadow after logging.

Bernie Krause: Yes, well, I just want to say one thing. You can hear how robust it is when it's a really vital habitat. Here it is a year later after logging.

[Recording played]

Bernie Krause: Here comes a woodpecker.

[Recording played]

Bernie Krause: The difference is palpable.

And these are the kinds of things we need to know about to make good decisions.

Greg Dalton: And that’s selective logging. You have clips where there is clear cutting and it’s even more dramatic. We won’t play those, but even more of a dramatic change. So that's species that had to move somewhere else because their habitat was destroyed.

Bernie Krause: Yes, and they never came back to that habitat again even though to our eye it looks perfect, to the eye and to the camera, you can frame a shot and it looks as if there isn’t a tree or a stick missing from that habitat. But of course our ears tell us a very different story.

Greg Dalton: That's interesting. I think so much of us look at Sierra Club calendars, look at nature, oh it looks okay but we’re not paying attention. We have another one that shows the impacts of climate change, so Bernie Krause tell us about Sugarloaf State Park.

Bernie Krause: Sugarloaf State Park is in the Mayacamas Mountains which borders Napa Valley in the east and Sonoma Valley in the west and I’ve been recording there for 20 years. And I have four 15-second recordings, first recorded in 2004, again in 2009, 2015 and 2016 and it shows how climate change because when I first started recording there spring occurred at a certain time of the year and now it’s two weeks earlier. You can see how climate change is affecting and the drought is affecting the bird populations. You will hear a nice robust peace in 2004, in 2015 nothing.

[Recording played]

Bernie Krause: This is 2004. Now we’re coming up on 2009. Spring is occurring two weeks earlier, bird populations are beginning to thin out.

Now, here comes 2014, 14 almost nothing, no screen. And 2015 absolutely nothing. Silent Spring. We had no birdsong where we lived in Sonoma Valley this year. This is the first time in 77 years I've experienced the spring without bird song.

Greg Dalton: Jason Mark, some people who don't know what they're missing, depends on people's baseline. If someone was born and when those sounds didn’t exist they don't know what they're missing, right? So is it possible that humanity is just going to adjust to a shifting baseline and not know the richness that Bernie Krause just showed us we’re losing?

Jason Mark: Yeah. It’s a real challenge for the conservation community to think about kind of what are we trying to save when we’re preserving nature. Because we’re essentially, you know, as a culture, as a society we’re on a kind of hamster wheel of collective amnesia. Because each generation is starting from again a different baseline. The baseline is always shifting. So what a baby boomer might remember as a degraded landscape would then for a Gen X-er be the norm. And even that then middle baseline, a Millennial will come along and might think it's like paradise, might think it’s rich and full and vibrant. And so it makes the work of conservation really hard; that’s why I think this sort of natural history recording whether it's film or photographs or video or audio is so important to be open sort of see as things have changed. But I think that it especially complicates things again in what some are calling the human age or the Anthropocene if the human insignia is everywhere what exactly is the nature that we’re trying to preserve.

And it’s not just academic navel-gazing, I mean, it really does make it hard for land managers on the ground to know, what are they trying to preserve? Is it a snapshot of a place and time, or is it the biological processes of recurrence, regeneration and restoration that a vibrant ecosystem would just engage in.

Greg Dalton: We’ve seen some of that here recently along the California coast where warm waters have brought food in which has brought dolphins swimming in Monterey Bay. My kids think it's great. Oh cool, I’m like, whoa I've never seen that in 50 years. But it’s like, oh dolphins and whales are swimming closer and isn’t that a good thing? We can see whales from the Golden Gate Bridge. Bernie Krause, not all bad, not all bad.

Bernie Krause: Not all bad. I remember when Humphrey swam up to Sacramento and we had to get him out so it depends. There are things that are happening where the natural world is always testing for optimum performance. And so whales are going to come in to test that. Birds are going to take up different territory and different places to live to survive because that's what the natural world wants to do. Living organisms want to survive. So those kinds of changes are going to take place. One of the things we might think about doing is, first of all, learning what these messages are through the soundscape because it's a really important way to learn that, and second what we want to do and how we want to frame this world for ourselves and our survivors, you know, our families and children, and so on. It’s really important to think about that.

Greg Dalton: Tanya Peterson, do zoos have a role in either documenting this change or, I mean, did you ever think about the shifting landscape, the migrations, the extinctions or you’re just looking as place and time for what is now?

Tanya Peterson: Well, first of all, I’ll just say if anybody's been to the San Francisco zoo you know it’s near the ocean and has historically been cold. Well with climate change, we’ve had warmer days than not so it maybe it’s good for attendance at the zoo. But we are actually trying to attract migratory species to be at the zoo without cages. We’re developing actually our coastal region to provide a safe haven for the migratory birds and other species coming along the coast. And we definitely are thinking that we should be a safe haven for other animals along the way as well. But mostly our mission is to educate, to let the Generation X’ers know the world might be something different in the near future if we don't take action.

Greg Dalton: And the beach is going to be waterfront here before too long. Is that on the horizon? Because actually the city has plans to move the highway, right, closer to you because the ocean is advancing.

Tanya Peterson: Yes, we will be one of the only zoos in the world actually on the ocean and we--

Greg Dalton: Not by choice.

[Laughs]

Tanya Peterson: You know, you make lemonade out of lemons as they say. So with that, you know the zoo is divided into conservation hot zones. We have Africa, Asia, wherever the current conservation issue is, and obviously now it's water. And so with this new situation we will be building the coast in as part of the zoo actually, and create an outpost for children to look safely at the ocean. For those of you in San Francisco, we have kids coming from Hunters Point, Bayview, they're excited to be at the zoo, they’re doubly excited to see the ocean. They had no idea San Francisco bordered the ocean. So they run across that great highway, you know, not safely, we try to escort them across. But now what we’re doing is building a platform so that they can experience the coast safely.

Greg Dalton: Interesting. Jason Mark, you write about Pete Singer in your book and animal rights. So tell us about that Peter Singer story.

Jason Mark: Well, I don’t get into Pete Singer too much. I guess Pete Singer comes in a chapter about the intrinsic rights of nature, which really I think would begin, you know, most powerfully with Aldo Leopold in the Sand County Almanac, in saying that there is a community of life beyond our own, beyond human civilization. As Thoreau says, wilderness is a civilization that's other than ours. And I’m just trying to make the point that I think a lot of the American environmental movement, the global environmental movement, as we’re facing these cascading eco-crises from climate change to the acidification of the oceans, a lot of the work has become out of necessity self-preservation. And I think it's important to keep in mind that a lot of the work we do and that you talk about so wonderfully here at Climate One all the time, you know, redesigning our cities, redesigning our technologies, redesigning our energy system, why are we doing it? So yes, we’re doing it for ourselves. But I would hope that it’s not just to save our bacon from a crisis. We ourselves manufactured that. At the end of the day the work whether it’s the San Francisco Zoo or from other conservation organizations, it's about trying to save a world worth saving, right? The beauty of the natural world and I think, you know, I’ve got a whole chapter kind of coming back and remembering that a lot of the wilderness movement is about safeguarding the intrinsic rights of other critters that are out there, that we don't just want to save nature for the instrumental value it provides us, for its ecosystem services, that these things have a got a right in and of themselves. And so that's where Pete Singer comes in sort of a line.

Greg Dalton: And that’s also where Pope Francis is talking about St. Francis communing with nature and St. Francis kind of giving sermons to flowers and that sort of thing. So Bernie Krause, Pope Francis has asked us this newly integrated ecology to think more about the inherent value of nature, do you think he's going to be good for your business and for your ethic?

Bernie Krause: Well, we’re nonprofit not by choice so.

[Laughs]

But our business end of things. But I think that he makes a really good point about preserving the natural world and becoming the stewards that we need to become in order to still have places to visit and places to go. I know for myself, I suffer from a terrible case of ADHD and have since I was a kid and the only thing -- and I'm talking about medication and everything else -- the only thing that has helped is connecting with the natural world and spending time out there, which is my main reason for doing that and learning to enjoy it in a peaceful, not aggressive or assertive way.

Greg Dalton: You write in your book about nature can help PTSD, forest bathing, you know, sort of like being out in nature under the canopy of trees is actually, ADHD aside, good for human health.

Bernie Krause: Yeah. There are many groups that still have connected to the natural world who when they feel stressed by the cash economies of the west or the Far East just disappear into the rainforest for months at a time to heal. And that distance that they are able to obtain by doing that, by just getting away from it all, is a remarkable analgesic for them.

Greg Dalton: You write about Mark Tramp, I think it is, the Institute for Music and Brain Science at UCLA, I mean, this is not just like, oh I feel good when I’m in nature; this is starting to be scientifically proven.

Bernie Krause: Yeah, I mean, it’s still a little bit anecdotal because the whole field of soundscape ecology is just a few years old.

But we’re beginning to think about doing studies that engage people who are in heavy medication or cancer survivors, stuff like that where they are listening now to natural soundscapes instead of music. Because music is culturally biased and often when music is introduced as Oliver Sacks has said in his book Musicophilia, sometimes also what's introduced as things like grand mal seizure or petit mal seizure just because of music. So even though people want to hear certain kinds of things it has a stress effect on them that we have been looking at.

Greg Dalton: And you also write about auto traffic can actually impair people's IQs at certain ages, I mean--

Bernie Krause: That’s a World Health Organization study.

Greg Dalton: That urban noise can impact human brain development and so those families moving to Marin may have a point. Okay.

Jason Mark: I mean, Bernie's work is so -- I mentioned Bernie's work in my book. It's so important what you’ve been doing Bernie for years to get this information about the natural world and it's really clear. I mean, I write in Satellites in the High Country about how when you go out to the deep wilderness, the one thing that’s going to remind you of civilization is going to be jet traffic. 20,000 flights a day, either small craft or jet airplanes taking off in this country. That is like the ultimate mark of civilization we’ve taken ownership of even the sky and it's so hard to get away from anthropogenic sound, you know. I went to the heart of the Olympic rainforest in part because it's supposed to be one of the few places in the lower 48, in the continental United States where you can sit for 15 minutes and not hear a human created sound. So I think actually this human din that’s around us is contributing to people’s sort of sense of what some people will feel as sort of a sense of claustrophobia, that there is no away, there’s no place to get to. And again Bernie's work has been so important to make us aware of that.

I want to go to our lightning round and ask each of you some brief fun yes or no questions starting with Bernie Krause. Some environmentalists can be righteous and annoying, yes or no?

Bernie Krause: Oh, yeah.

[Laughs]

Greg Dalton: None in this room. Yeah, you sound like you know some. Jason Mark, some environmentalists are against everything.

Jason Mark: Yes. Stop the madness.

Greg Dalton: Tanya Peterson, zoos are to nature as Pringles are to food.

Tanya Peterson: I’m going to say no to that.

[Laughs]

Bernie Krause: Greg, where did you get these?

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: I have a drink upstairs and make ‘em up, yeah, I don’t know.

Tanya Peterson: I do like Pringles though.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: I was reading these earlier and several of the crew said, oh Pringles, yes! Jason Mark, zoos and aquariums educate children and give them a chance to see and understand animals they’d never otherwise see.

Jason Mark: Yes.

Greg Dalton: Tanya Peterson, it is offensive for circuses and marine entertainment parks to force animals into mimicking human behavior; dolphins that kiss people and elephants that ride bicycles.

Tanya Peterson: Yes.

Greg Dalton: Tanya Peterson at the grocery store do you select free range eggs and meat?

Tanya Peterson: Yes. I rarely eat meat but--

Greg Dalton: When you do?

Tanya Peterson: When I do, when I have company.

Greg Dalton: Bernie Krause are you vegetarian?

Bernie Krause: No.

Greg Dalton: Jason Mark?

Jason Mark: No.

Greg Dalton: I'm not either, well 80% of the time. Jason Mark, some people in your generation consider climate impacts when deciding how many children to have.

Jason Mark: Yeah.

Greg Dalton: Would you?

Jason Mark: I am, yeah. It’s an open conversation in my family still, but I'm committed to one and done.

Tanya Peterson, selling licenses to kill big game is a good way to generate money for their preservation.

Tanya Peterson: No. I strongly disagree with that.

Greg Dalton: Tanya, animals living free are more content than animals living in captivity. Captive animals pay a price for helping educate people.

Tanya Peterson: You know, I would say it depends. Animals in the wild suffer from drought, starvation, poaching. We have animals at the zoo living much longer than animals in the wild. It certainly depends on the situation.

Greg Dalton: So animals in the zoo get room service, so that's okay. Bernie Krause, you have played sounds of nature to get your wife in a romantic mood.

Bernie Krause: You’re asking me?

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: You’re the sound guy, your wife is here so, you know.

Tanya Peterson: Maybe we should ask her.

Greg Dalton: And can you sell those CDs for those in the audience, you know.

Bernie Krause: Kat is sitting right there.

Greg Dalton: People on the radio can’t see you blushing.

So we’ve been talking about the sanctity of nature. I want to ask you about GMOs. Jason Mark, GMOs, some people think GMOs will be necessary to feed a world with 9 billion people. We’ve been talking about the inner value of nature; GMOs are kind of tinkering with nature. Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

Jason Mark: My concerns around GMO have less to do with biological ecology than political ecology. And the question is do we want a small number of corporations to be essentially controlling the global food supply through their dominance of the seed markets. I mean, in general humans have been tinkerers for a long time. One could say that a hybrid, you know, any sort of hybrids would be unnatural in a way because they’ve been crossbred by humans. So my bigger concern is one again of political ecology, but certainly figuring out how to feed a global population is the biggest test of how much space we’re going to be able to allow for wildness in the world and space for other critters. We need to not just share land, we need to spare land. And so I think we need to increasingly intensify agriculture. I just want to make clear that’s different from industrializing agriculture. There are ways to intensify agriculture that are based in principles of Agro ecology. The trick there is it involves more people on the land and what we've seen for the past couple millennium is a move towards urbanization and at the same time we also do need to make our cities denser. So there's a couple of competing tensions there. But in general I would consider myself a GM skeptic for reasons of again political economy.

Greg Dalton: The reason a lot of people are against GMOs are that they think they're bad for human health, which really hasn't been proven, or because Monsanto is evil, et cetera, rather than the industrial monoculture and kind of the controlling power that you just described. Is that fair to say, that a lot of people are opposed to GMOs for reasons because they worry about Frankenfood or other things?

Jason Mark: Sure, I think that’s exactly right. Most people are concerned about GMOs because they have a gut level reaction to the manipulation.

And this just goes to show I think that the product of modernity remains contested terrain, you know. Michael Grunwald, a politico, wrote this piece kind of taking down Pope Francis’ encyclical and saying it was weird. And I got on this weird little -- it happens now the 21st century, this weird little Twitter back and forth with Grunwald saying, well I didn’t find it weird, I think actually the Pope was expressing the feeling many people have of unease with technological change. And that is not limited to the political left or the political right. It actually crosses a lot of boundaries or political boundaries we have in this country. So the more interesting question I think is parsing and looking at what are the good things of modernity? I'm in favor of tetanus vaccinations and antibiotics; and what are the bad things about modernity, cultural alienation, alienation from nature and of course the way that we’re consuming the planet. So you’ve got to kind of parse these things I think and think about, you know, what are the good and the bad and not throwing it all at once.

Greg Dalton: Not as big thing as some people make it out to be. I want to talk about art. Bernie Krause, Become an Ocean was a piece that you write about John Luther Adams, it’s sort of the melting tundra and loss of sea ice and tell us about Become an Ocean.

Bernie Krause: Well, John Luther Adams is a composer from Alaska. He's often confused with the Lower 48 John Adams, but he's written this piece about, which was performed by the Seattle Symphony Orchestra a couple of years ago, got a wonderful review in most of the papers. And it really speaks to an issue that's very important, and he's trying to bring the ideas of ecology and sustainability into an art framework.

I know that we’ve done something very similar with The Great Animal Orchestra. We actually composed a piece that was commissioned by the BBC Symphony Orchestra last year and which included for the first time live animal sounds with a 70-piece orchestra and it was way cool.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: I was thinking of Peter and the Wolf when you were talking about that. And Jason Mark you write a lot about wolves in your book. They are in danger. There is a tension between livestock and hunting of the wolves. The reintroduction of the wolf in the American West has been a big story, controversial story. Where is it now?

Jason Mark: Where is it now? Well it continues its, you know, you almost need like a scorecard to follow is the wolf on or off the endangered species; that it almost goes state by state according to what federal courts have ruled. But yeah, I tell the story of, you know, the wolf has long been the kind of totem of wildness for a lot of people. Adolph Murie, a famous 20th century wildlife biologist, called the wolf’s howl the voice of the wilderness. Poet Gary Snyder says you know putting predators back on the land is ecology on the level where it counts.

And then you also have like a great outdoorsman like Teddy Roosevelt saying the wolf is the beast of waste in desolation. So, you know, we’ve always kind of projected our feelings about wildness and wilderness onto this animal and I follow the story of this subspecies of wolves. The Mexican gray wolves down the Gila wilderness. There’s only 106 of them, there’s about a couple hundred, I think that's 300 now in captive breeding programs across the country, but 100 out on the landscape and they are probably, those 106 animals are probably the most closely monitored and managed wildlife on the planet, I think it’s fair to say. Just the intensity with which federal and state wildlife agents have to track them every week; partially to protect them because poaching and illegal killing of them, because that population is still on the endangered species list is the number one cause of mortality. And so it’s this wonderful story with all these conflicting parts. The wolves are certainly wild, they’re out there on the landscape, they’re eating cattle, but eating cattle, eating elk, they’re behaving as wolves, but they are not exactly free. They’re living in the matrix as much as we are. I mean, they are so carefully managed. And so it was just an emblem, I guess, so it was emblematic of the tensions around wildness today. I mean, it’s hard to kind of think about what wildness means when you think about wolves that are out there and they’re all wearing GPS collars, they all have PIT tags personal, you know, the kind of tags that you put in their cats or dogs, there’s a Social Security like number and a vaccination history. So are these animals really wild? And it’s a fascinating story.

Greg Dalton: And you quote one person who says that they are a four-legged Al Qaeda. The ranchers really don't like the predators, even though they’re healthy for ecosystems, they’re bad for rancher’s business.

Jason Mark: There's no question about that I mean and I think the reason why our relationship with wolves have always been, once you strip away all the symbolism, what you get is the fact of brutal competition. Wolves are antagonistic to our interests or there's an innate conflict of interest at least if we are not going to be vegetarians. If you are eating meat, there's going to be a conflict between our interest and the wolves’ interests. And so that’s what makes it tough. And the ranchers at some level have a legitimate concern, but it then starts to become, it becomes clouded with I think what I found to be paranoia.

Greg Dalton: Tanya Peterson, any wolves in captivity?

Tanya Peterson: It’s interesting you brought up the wolves because we’ve been asked to bring in two wolves, actually the Mexican wolf that was just described, and we happily will. We also have two wolverines. And again I think some of it is just a misconception. My understanding and our observations are the wolves really go after the weaker of the herd, which in some ways may be beneficial.

Greg Dalton: That’s nature.

Tanya Peterson: That’s nature. And so again, with all due respect to those in the industry, I think they have overhyped the situation. Again this is where I think as you can play a role. If the wolf needs help, we have the space for converting all the old polar bear exhibits into wolf terrain and we can play a part in conservation. We do have two wolverines, they are just as mighty and ferocious, smaller but and they seem to attract a lot of University of Michigan fans.

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining us, we’re talking about the sounds of nature at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club. Our guests are Tanya Peterson, from the San Francisco Zoo. Soundscape artist, Bernie Krause and author Jason Mark. I’m Greg Dalton. We’ll be back after this break.

[Climate One Minute]

Announcer: And now, here's a Climate One Minute.

There's no question that the natural world is worth saving for its own sake, if not for ours. But is there an economic trade-off? Tony Juniper is a sustainability professor at the University of Cambridge. As he points out in his book What Has Nature Ever Done for Us? How Money Really Does Grow on Trees, the cost-saving decisions that are made by corporations and governments are based on what he calls "the greatest misconception in history."

Tony Juniper: The idea is that investing in nature, protecting the environment, looking after ecology; it seems a cost that is hostile to the process of improving progress, economic growth and the betterment of human welfare. My point, based upon what I have regard to be a vast amount of compelling evidence, shows the opposite to be the case: that nature is in fact the underpinning of the global economy and in fact the economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of nature, not the other way around.

Because in the end we rely on soils, freshwater, clean air, the replenishment of oxygen, pollinating insects, the protection of coasts by mangroves and coral reefs, the soaking up of carbon dioxide by forests and soils. All of these things, if you start to add together the economic contribution they're making, one estimate held is about double global GDP. And yet the bit of the economy that we're measuring, the bit where we actually look at the economic growth in traditional terms, is based upon the plundering of this other part of the economy which is worth twice as much.

And so what I'm trying to do in What Has Nature Ever Done for Us? is to overturn this misconception and to generate a new narrative in economics which is about seeing nature as an essential ally in the process of economic growth, not something that's hostile to it.

Announcer: That's Tony Juniper, author and sustainability expert, speaking with Climate One in 2013. Now, back to Greg Dalton and his guests at the Commonwealth Club.

[End Climate One Minute]

Greg Dalton: Bernie Krause, you talk about snowmobiles in National Parks. And for someone who, I love Wyoming, Jackson Hole and I thought about, wow, would it be neat to go there in the winter and take a snowmobile and I think, oh what about the sound. And tell us about your story about snowmobiles in the parks.

Bernie Krause: Well, I was asked by the National Park Service to go and record the sound level of snowmobiles on the parks and it was the time when they were using two cycle engines. And they would have literally thousands of snowmobiles allowed into the park every day. It was beginning to cause pollution. It was a huge amount of noise, and so I went up there in the early 2000's and recorded not only the snowmobiles going by, but also the sound level, sound pressure level which exceeded something like 90 dB, 95 dB. And at one point the congressional group that was asked to come up and see these things for themselves because they were going to vote on whether snowmobiles should be allowed in the parks. At one point I just set up a room like this and with speakers in the room and I measured the sound pressure level of the snowmobiles going by and reintroduced it into the room at the center of the room.

And when these guys and they were all guys of course, came in to listen to the sound. And I said I have something I’m going to play for you two and a half minutes each one, of snowmobiles going by and the other of the natural soundscape as it is when it's quiet. And so I played the sounds for them and when the snowmobiles came by and it came up to around 95 dB, they were blocking their ears and screaming and yelling and saying, turn down the sound. And I said, no I won’t do that; this is what you're voting on. And it turns out that it was a split vote, it was 210 to 210 and Dick Cheney had the deciding vote.

Greg Dalton: I guess we know which way that one went. Bernie Krause, lot of fires in the west these days. Have you ever done soundscapes of fire?

Bernie Krause: I have. I have recorded fires before. Done mostly in the Southeast in the Everglades in around Florida because I was doing an exhibit I was doing a soundscape exhibit for Corkscrew Swamp, the park down there at Corkscrew Swamp.

Greg Dalton: And Jason Mark, this is a natural phenomenon. Yellowstone burned, people got all upset that Yellowstone was not the way, you know, I wanted to remember it. But now Yellowstone's come back, I’ve been there, right? I mean are these far, maybe the human cost element is the drought and there's some human aspects of it, but fire’s natural, what’s the big deal?

Jason Mark: The big deal is that we’ve sprinkled our homes throughout the forests, and now when we have a forest fire or a wildfire it puts in jeopardy, people's homes, lives and property. But yes, I mean forest is a natural part of, you know, certainly ecosystems throughout California and in the mountain west and we need them. And if anything, you know, a century worth of fire suppression has just built up these intolerable fuel loads. And most of the time when a fire comes to even a high intensity firewood it leaves behind is a mosaic. And that's what natural systems want, right; you want a mosaic of different stages of the forests that’s going to provide more habitat to a broader range of critters.

I like to think, you know, the forest service now is seeing how much of its budget is cannibalized by forest firefighting. In some states, you know, Washington State, I did talk to a fire ecologist, a guy named Chad Hansen just last week. And he was saying, you know, Washington State with its mega fires last two seasons is maybe being a little smarter than Cal fire is. Retreating from wild lands forest firefighting where you don't need to do it, let it burn, and instead retrench back to places we do want to protect lives and property. But yes, fire is a natural part of the landscape I think what’s going to be hard and this gets back to the shifting baseline is, with rising temperatures and in some places diminished or changed rainfall patterns, the ecosystem may not come back to the way we remember it. You might see Ponderosa say groves turn into a Pinon-Juniper mix or a Pinon-Juniper mix changing over to Chaparral. That’s going to be hard for people to wrap their minds around. You know how and this is I think again the challenge is kind of wilderness in the human age, is how do we continue to have an intimate emotional relationship with landscapes, even as those landscapes change before our eyes. As the ocean gets closer to the San Francisco Zoo, how does -- our memory of Ocean Beach is going to change. Or I should say, maybe our memory’s going to stay the same but the actual landscape is going to change.

And I think again it’s a big challenge for the conservation community. How do we sustain our love say for Sequoia National Park, if the Sequoias start to move northward or up in, you know, altitude elevation on the range? Or Joshua tree, you know, what are we going to do if there's no Joshua trees in Joshua Tree National Park, or no glaciers in Glacier National Park. It’s going to make these things a lot tougher.

Greg Dalton: Rebranding opportunity. I want to ask each of you, we’re going to audience questions soon. Your favorite place in nature, Tanya Peterson, do you have one?

Tanya Peterson: It is the ocean. There’s a peacefulness and a calm that comes with it.

Greg Dalton: From whence we came, John Kennedy said. Bernie Krause?

Bernie Krause: I love Alaska. I go there any time I can. 600,000 people and change and a place almost a third of the United States.

Greg Dalton: Any particular part of Alaska, southeast or up in the Kenai?

Bernie Krause: I love it all.

Greg Dalton: Jason Mark?

Jason Mark: I would say for that kind of sense of being in the deep remote wilderness, the Gila Wilderness in the southwest is pretty hard to beat. But for an experience on what I call the nearby nature, I love Point Reyes National Seashore. And we’re so lucky to have a place like that right around backyard that you can get to in an hour, you know, from right here in the city. So, it’s an incredible resource that we have.

Greg Dalton: And for those who love Point Reyes as I do, there’s a wonderful film called Rebels With A Cause, it’s the creation story of Point Reyes National Seashore and really it’s a zoning law, tension with the agricultural interests, ranchers, and the enviros and it’s a fascinating story.

I want to talk with you before we go to our audience questions about how you talk to climate skeptics. You’re all very knowledgeable about climate change. Bernie Krause, you encounter someone that doesn't value nature as much as you do, is like yeah what about the sound of this frog, I don't care. How do you talk to someone about climate change who’s not clear that it's happening, or that's a big concern to them?

Bernie Krause: What I typically do is I'll just invite them to listen to these sounds and ask them, I mean and I have them from all over the world, both marine and terrestrial. And I’ll just ask them, is this important to you? And does this, this is an expression of life of living organisms. How important is this to you in your life and do you consider making that important? And then if they really want to get down into facts my PhD is in bioacoustics I can certainly quote facts and sources for them.

Greg Dalton: Tanya Peterson. Do you have ever have occasion to talk to skeptics?

Tanya Peterson: I just invite them to the zoo and say, hey, look how much warmer it is at the San Francisco Zoo than it used to be. No, in truth though, I often point to the species impacted. For example turtles, their sex is dependent upon the climate and temperature. And so, I believe if it’s warmer there are more female turtles born. Examples like that, showing the facts and what the impact is we are seeing and we’re participating now in studies to try to neutralize that. You know, and actually breed the male turtles at the zoos to counter effect the situation. So I think with examples like that and cite the evidence.

Greg Dalton: Jason Mark, some people think that facts don’t persuade people that facts don’t do it. Facts don’t convert people, facts can be contentious, they can be argued, a lot of people are not scientists, get lost quickly on facts. How do you talk to a skeptic?

Jason Mark: It's really funny you said that, cause I was sitting over here kind of thinking about that; you know, issues on confirmation bias and how people sort of going to cherry pick their own evidence is really problematic. And, you know, my first instinct is to say well if you went to 100 doctors and 98 of them said you've got, you know, cancer you would you’d go get treatment, you wouldn't listen to the 2% who said maybe you got cancer. But again, I don't know that that's the most persuasive, the most persuasive argument. And I actually think that in some ways the environmental movement hasn't done a good job; it's over relied a little bit too much on science. And, you know, facts are going to make the case, and I think actually moral arguments at the end of the day are going to make more people want to either change their minds and or take action. And really coming back to just, you know, real punch in the gut sort of stuff of like, what's the world you want for your kids. I think those moral arguments are more likely to change hearts and minds and kind of laying out the bar graph or the pie chart of this is what you know these many AAAS scientists say.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about nature and climate change at Climate One. Jason Mark is editor of the Earth Island Journal; also today with us is soundscape artist Bernie Krause and Tanya Peterson, head of the San Francisco Zoo. I’m Greg Dalton.

We’re going to go to our audience questions. Welcome to Climate One.

Carter Brooks: Hi, Carter Brooks, artist and philosopher of Climate Art. So my question is about the value of witnessing nature as it’s degrading. Nature’s used so much in by environmental movement is as just as a motivator for action rather than witnessing and accepting some of this degradation that’s happening now over time. So like, how important do you think or what might any of the panelists say about this dynamic and the importance of carving out enough space for this for witnessing?

Greg Dalton: Who’d like to tackle that, Jason Mark?

Jason Mark: I think the last chapter of my book, I shadow some young men, they were all men, ages 17 to 21 on a mountaineering course in the Rockies. And there is this one really smart, thoughtful kid named Pat from Bethesda, Maryland, and we’re sitting there, I’m doing an interview with him with my audio recorder and he says, I did not expect to see all these dead husks. Because there we are in the southern Rockies where the pine beetle bark beetle devastation is really just you know, torn apart coniferous forests. And so he's thinking I’m going from Bethesda, Maryland I’m going to go out to the West and the Rockies and it’s going to be this wonderful alpine scenery. And it is unmistakable in the mountains above Vail, Colorado. You can see the whole hillside streaked with that the conifer die offs.

And at the same time he was awed by the scenery the alpine scenery, the Rockies, so it's kind of both, right? I mean at one hand he's having this profound emotional experience through the sheer physical beauty of the place. But then, yes, the unmistakable I guess we can call disease in the forest at this point was shocking him. So yes I do think we need to do some of that witnessing and it's going to be hard and I think it's -- hopefully it will be cathartic and that people will take from it a new sense of urgency.

Greg Dalton: Jason Mark, explain the pine bark beetle is happening because the warming temperature, and what impact does that have on bears.

Greg Dalton: On their habitats --

Jason Mark: Oh well, yes I think in the Northern Rockies what you’re seeing is you’ve got bears who rely on part of the year on pine nuts for part of their diet. They’re not getting that in their diets and --- but the larger consequences are probably for birds. Maybe some birds are benefitting from the snag but others aren’t. But yes, I mean it’s a whole ripple effect there’s a trophic cascade happening at some level when you see those trees dying back.

Greg Dalton: I want to talk to you about ask you, what gives you hope? We’ve been talking about things are going not so well.

Bernie Krause, is there a positive story where you’re seeing a rebound of an ecosystem? Give us something to hold on to you before we slip into the darkness.

Bernie Krause: Well, it’s -- I have seen rebounds of systems. Certainly in Costa Rica which is subtropical and I've seen the regeneration of some of the forests there. But then the landscape is very different. The soil is very different than it is in the Amazon or rain forests in Africa or Indonesia. But one of the things that gives me hope is I go out and I give these talks in schools all the time, and typically when I’m talking to third and fourth graders they're always coming up and asking me, because I do something which is really fun as well as helpful. But they always come up and ask me how can I do what you do? And then you get to this fifth and sixth and seventh graders and there's always some guy usually guy in the background, he’s going to raise his hand and he's gonna say how much money do you make?

And so it gets to that kind of thing you see the pyramid of information and acculturation as it as it grows. But my hope is the young kids, the ones who are asking how can I do what you do. And if there's any way that I can engage them, and I do that all the time, my phone and email is always open.

Greg Dalton: Jason Mark, hope?

Jason Mark: Yeah, you know there's this stereotype around you know folks who really care, sort of wilderness aficionados people who engage in backcountry recreation, that it’s usually kind of endeavor for white folks or an affluent white folks. And I’m really, you know, been given a lot of hope when I look at the -- I went to the art of a woman name Rue Mapp, she’s got a group called Outdoor Afro committed to getting more African American communities engaged in outdoor recreation.

There’s also a group called now Latino Outdoors doing the same work. And so when I think about the work and Latino Outdoors usually, you know, work close with the Sierra Club another big conservation groups to get the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument, right outside Los Angeles, designated by President Obama. So I look at the work that Rue Mapp and Outdoor Afro is doing or the work from Latino Outdoors are doing to try to ensure that the 21st century conservation movement reflects the ethnic diversity this country, that gives me a lot of hope.

Greg Dalton: Because if the parks are just upper-middle-class white people that’s not going to have a base or constituency.

Jason Mark: Exactly.

Greg Dalton: Tanya Peterson, hopeful?

Tanya Peterson: Yeah, every time we save a species by collective effort or otherwise, I have hope. You know, San Francisco Zoo and other zoos participated in efforts to get the -- remove the bald eagle from the endangered species list. And I say to our team we’re really here to try to put ourselves out of a job and get some of these animals off the list. Most recently some of the pond turtles and yellow legged frogs and so forth. So that gives me hope when you see a collective effort nationwide to save a species.

Greg Dalton: And also marine protected areas. Other people I’ve talked to have really seen rebounds in fisheries and in areas that are sort of these national parks in the seas. Let’s go to our next question, welcome to Climate One.

Male Participant: My name is Raul, I come from business background. So in my assessment, a lot of the damage for the nature and climate conservation has happened because of, you know, efforts not put forth by corporations private enterprise and profit motive individuals. So, are there some concerted effort within the community to really incentivize these private enterprises to be included in this movement, so that there is something genuinely in it for them, or should it be relegated to the CSR reports of the corporations?

Greg Dalton: Jason Mark, companies are valuing nature for the economic benefits that it delivers to humans and businesses.

Jason Mark: Yeah, I mentioned this earlier briefly, it’s this idea of ecosystem services trying to figure out can we put up a real price tag on all of the things that nature does anyway that actually serves us very well. You know, the city of Los Angeles is spending -- and I want to make sure to get the numbers roughly right - but spends something like $1 billion a year getting water into the city and spends $1 billion a year getting water out of the city through its rainwater management and that doesn’t make any sense. We’ve sort of because we remove the natural systems from, their natural functions from the system, right. And thinking about ecosystem services; how does nature only provide things like storm water removal. And that's a really important effort and you know I think you look at the work that Mark Tercek has done with The Nature Conservancy try to work with big corporations to do that.

I do think it's got limitations; I think at the end of the day corporations if push comes to shove and it's make money or tear out the forest, they’re going to make money. But I do think the ecosystem services work has got a lot of real benefit of, you know, around the edges and changing I think cultures within large corporations.

Greg Dalton: And one classic example is factories; companies used to be worried about what happens inside their fence and they’re now starting think about that where that water comes from and protecting a watershed upstream because that helps them get their water supply. So kind of going beyond their traditional boundaries to think about nature that helps them.

Let’s go to our next question, welcome.

Male Participant: Thanks for a really good program. I'm curious, how much of the information that you put forth here tonight gets to state and national legislators?

Greg Dalton: Bernie Krause, you’ve mentioned snowmobiles and legislators. How about other legislators who’ve heard your soundscape of human impacts and climate?

Bernie Krause: Well, there are many who have and it really depends upon their level of curiosity, how much they want to really know about the living world. And how much they want to learn. And if they're willing to take the risk of challenging their own intractable views of things, I think that they're going to come to some conclusions that are really helpful and moral and ethical and you know are going to preserve a lot of the stuff that we’re talking about today.

Greg Dalton: I want to wrap up by asking you of what you do in your own life to minimize your own carbon footprint. And I’ll first of all ask Tanya what you do and at the zoo to minimize your carbon impact?

Tanya Peterson: Well, you know, we try taking those baby steps as much as we can in a number of areas, but we're trying to eradicate the plastic bottle at the San Francisco Zoo. So we have the water filling stations. We now serve the water in the boxed water or pitchers: again one small effort to eradicate. We have the electrical charging stations at the zoo we have compost we’re actually one of the experiments with greywater, we’re working with the PUC now, you know, if you’re comfortable hosing down animals you may be comfortable taking a shower in the greywater as well. So wherever the efforts we can to participate in preserving our resources, we certainly do.

Greg Dalton: Bernie Krause, and also what can an average person -- what are you doing, what can an average person do to really make an impact in a meaningful way?

Bernie Krause: Well just in our personal life. My wife and I live in a rammed earth house; it’s not made of forest products. We are solar, pretty much solar operated as far as our power is concerned. And the house came with a pool, and we've eliminated chlorine in the pool by dropping salt in it and running electric charge across the salt and it separates the chloride from the sodium and we have natural chlorine. So it doesn't spend a lot of time with --

Greg Dalton: Wait, you electrify your pool is that what I just heard?

Bernie Krause: Yeah, it’s an interesting experience.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: You probably swim pretty fast, okay.

Bernie Krause: Yeah, yeah, we got a lot of exercise.

Greg Dalton: Okay. Jason Mark.

Jason Mark: Well you asked earlier if I was vegetarian, I’m not but I have for the last couple of years no beef on my diet just because greenhouse gas intensity of beef compared to pork or chicken is a lot greater. So I removed beef from my diet, you know, the car mostly sits on the street and gathers dust most days of the week and take BART and bike. In terms of what people can do, I really do think it is about, you know, finding that little patch of nature, you know, as much as we need the big remote wilderness for many different reasons. Finding that little patch of the nearby nature close to home, getting out to the seashore or the woods and again remembering why we want to do this work in the first place. It is as I said earlier a planet worth saving.

Greg Dalton: Well, perfect place to end it there. Our thanks to Jason Mark from Earth Island Journal, Bernie Krause a soundscape artist and Tanya Peterson from the San Francisco Zoo. I'm Greg Dalton. I’d like to thank audience here the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco and online and on air. Thank you all for coming and listening.

[Applause]