30x30: This Land Is Whose Land?

Guests

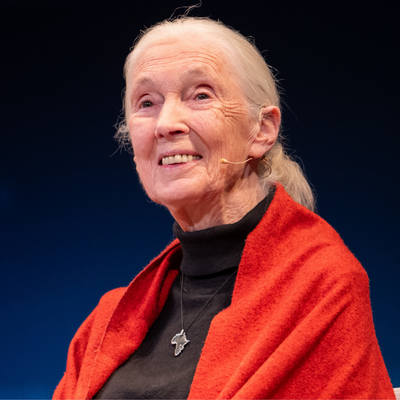

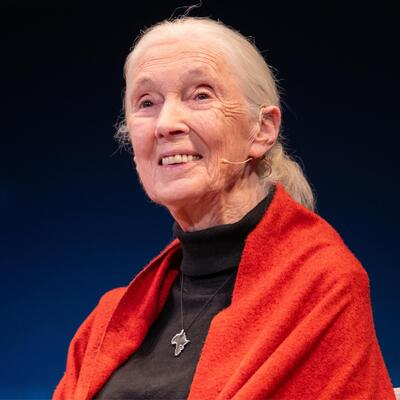

Paula J. Ehrlich

Catherine E. Semcer

Jennifer Norris

Woody Lee

Summary

This episode was underwritten in part by Resources Legacy Fund.

President Biden has set a goal of conserving 30% of the nation’s land and waters in the next decade to sustain essential biodiversity and strengthen the resilience of the natural systems upon which all life, including humans, depends.

A 2019 UN report warned that one million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction.

“The extinction rate is currently a thousand times higher than any time in human history. And it's estimated that we’ll lose half our planet species by the end of the century,” says Paula Ehrlich, CEO of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and cofounder of the Half-Earth Project, which advocates for conserving half the land and sea to safeguard most of the planet’s biodiversity.

“It matters because the species of our planet don’t exist in isolation...if we lose species, we lose the ecosystems, the intricate web of life that sustains nature and sustains us as part of nature,” she says. Ehrlich describes Half-Earth and 30x30 as “moonshot” goals that can inspire humanity to accomplish great things.

Conservation organizations across the country lauded Biden’s 30x30 executive order. But it drew immediate criticism from some rural parts of the country where much of the land is in farming and ranching. In states like Nebraska and Kansas, where nearly the entire state is under private ownership, some have raised concerns about where, and how, the federal government plans to set aside those acres.

Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts has described 30x30 as a “land grab” and issued his own executive order directing state agencies to quote “resist and prevent the federal government’s attempt to usurp state authority” as they work toward the 30x30 goal.

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack has said the government will support local and federal voluntary conservation programs in line with the 30x30 goal.

“The intent is not to take away anybody's private property. The intent is not to restrict anybody's economic activity. The intent is to reward good stewardship and continue providing the goods and services our economy needs to thrive,” says Catherine Semcer, research fellow with the Property and Environment Research Center.

She says the Biden administration needs to focus on engagement: getting more input and consulting with those who will be most impacted, particularly private landowners who control a lot of critical habitats like grasslands and wetlands. And there are financial resources outside the government that can be brought to bear, she says.

“Much like climate, the challenge of ecological degradation is so large and so vast this is going to take a whole of society effort. It's not something the government can solve alone. So, engaging the private sector, be it individual landowners or large institutions, is going to be absolutely critical to the success of this initiative,” Semcer says.

Woody Lee, executive director of Utah Diné Bikéyah, agrees that consultation and consent is critical, especially for tribal nations. He’s a member of the Navajo Nation, which has endorsed 30x30.

“A lot of the things that we do every day depends on whether or not it is okay with the BIA [Bureau of Indian Affairs] or the federal government,” he says. “We cannot actually build dams to recharge our watershed — those are some of the policies that really deters us from self-sustaining ways of thinking...those types of strings need to be changed and to where 30x30 would make a difference of how the government is denying us of taking care of our own land by denying us of certain access and certain ways of doing things to advance our ways of thinking, of taking care of the land.”

Related Links:

Half-Earth Project

America The Beautiful Plan

California’s 30x30 Plan

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. President Biden has set a goal of conserving 30 percent of our land and waters in the next decade to sustain essential biodiversity.

Paula Ehrlich: If we lose species, we lose the ecosystems, the intricate web of life that sustains nature and sustains us as part of nature.

Greg Dalton: Yet some are worried about how the program will work when so much land is privately owned.

Catherine Semcer: The intent is not to take away anybody's private property. The intent is not to restrict anybody's economic activity. The intent is to reward good stewardship and continue providing the goods and services our economy needs to thrive.

Greg Dalton: So what are the steps to ensure an equitable approach that accomplishes the conservation goals?

Jennifer Norris: The Biden administration has put out their framework and now the next step really is to engage with those communities across the country at the local level, you know, what are the priorities. What are the obstacles and how do we overcome those together?

Greg Dalton: A deep dive into the 30 by 30 conservation plan, up next on Climate One.

Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. I’m Greg Dalton. The IPCC recently released a new scientific report ahead of the upcoming climate summit in Glasgow. The headlines are familiar and scary. Human caused climate change is everywhere - now - and is accelerating. UN Secretary-General António Guterres called the report “code red for humanity.” Fossil-fueled droughts, heat waves, intense rainfall--and all the associated impacts we are experiencing will become more intense and frequent. But with immediate action the report lays out possibilities for reducing future harm. It’s not too late to make a difference, if governments act together, quickly. We’ll have more on the latest IPCC science in our show next week. Now, we turn to a promising path for climate progress - conserving enough land and water to protect Earth’s biodiversity - and we humans that depend on it.

Greg Dalton: One million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction. Paula Ehrlich is CEO of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and cofounder of the Half-Earth Project, which advocates for conserving half the land and sea to safeguard most of the planet’s biodiversity.

Paula Ehrlich: Extinction usually unfolds off stage so these huge numbers made a big splash because they were kind of a surprise but we started to pay attention. There are two things that were happening there that were sharpening our pencil on this. One, gob smacking science and two a shift in consciousness, right. Because when this whole, the story hit the page it mattered because somewhere in the core of our humanity, we recognize these creatures great and small. Even when we’re touched by their story, we feel extraordinary compassion, maybe even a moral conviction to act to protect them. But here's the other thing about the gobsmacking science and why it’s gobsmacking. It matters because the species of our planet don’t exist in isolation. The answers if we lose species, we lose the ecosystems the intricate web of life that sustains nature and sustains us as part of nature. Human beings are connected with all of life. The organisms that surround us in such beautiful profusion have evolved over 3.8 billion years to create an exquisite and careful balance of interconnected resilience. And knowing this really coming to know and understand this is critically important as the namesake of our foundation E.O. Wilson once wrote, the more closely we identify ourselves with the rest of life, the more quickly we’ll be able to discover the sources of human sensibility and acquire the knowledge on which an enduring ethic, a sense of preferred direction can be built. So, in creating the Half-Earth goal, E.O. Wilson was inspiring the conservation movement to move from a process which somewhat successful in addressing the extinction crisis to a goal. And having a goal is a big deal. It's not just important conceptually it’s also important inspirationally, right. Because if you look at history this is a sort of ambition it’s the sort of moonshot that drives humanity. You know like you can probably remember when John F. Kennedy announced the space program, he did not say that the American people by the end of this decade will make good progress towards landing a man on the moon and bringing them home. He didn't say what made good progress, he said by the end of this decade we’ll send a 300-foot rocket on an untried mission to an unknown celestial body 240,000 miles away and then return it safely to earth. And our collective imagination exploded, right, we can do it, right. So, that’s the problem we face and also what Half-Earth is about. It's a goal that's meant to inspire us in the same way.

Greg Dalton: So, that Half-Earth I remember when that concept came out and like wow, okay, that’s bold half that's big. And that's now kind of evolved into 30 by 30, you know, several states, the Biden administration, state of California have developed this 30 by 30 framework. So, tell us what that is and how that can be implemented and what it would do.

Paula Ehrlich: In 2016 E.O. Wilson wrote a book called Half-Earth. And in that book was a sort of a promise that if we protected half the earth’s land and sea that we would manage sufficient habitat to safeguard the bulk of biodiversity. That we’d solve what E.O. Wilson calls the next big thing, the thing we need to turn our attention to beyond the changing climate, and that is the extinction crisis. Extinction is a crisis because the extinction rate is currently a thousand times higher than any time in human history. And it's estimated that we’ll lose half our planet species by the end of the century. So, the book Half-Earth and the Half-Earth project are about solving that problem. Now, it’s pretty intuitive that the number of species that a habitat can sustainably support increases with size. And that's why we set forth these ambitious targets like 30 by 30. And currently we have about 15% of lands across the globe protected. 15%. The current amount of global protection is not good. The math would predict we’ll lose half of all species by then, before the end of the century. Now, 30% is better and so that's what inspires the goal of 30 by 30.

Greg Dalton: So, doubling that in one decade that sounds pretty ambitious. And what does that actually mean? Does that mean no roads, is this humans stay out, you know, this is nature's place or how humans fit into that?

Paula Ehrlich: That’s been the biggest challenge is to help people imagine what it would look like for themselves for our planet for species and for many aspects of our ultimate sustainability. If the goal is to protect the web of life for all of life to sustainability endure, then whatever our target is 30 by 30 or half where we pick to prioritize for conservation becomes particularly important. And you asked these roadless places these places without people. They are all of those things and none of those things. It’s because not all places are equally effective at protecting biodiversity. Each species has its own important place in the world that we need to kinda keep in mind. So, let's say we determine conservation priorities based upon the most charismatic species or the most beautiful vistas and our favorite places. That's wonderful, but it may also favor the species in already well studied places over those that are less well-known and could perversely increase overall species extinction. So, we might lose important strands that are holding together the web of life without even knowing it. So, the next big thing the moonshot mission from the moon is to completely catalog and map all the biodiversity on earth so that we don't make that mistake.

Greg Dalton: Are you trying to conserve nature for nature sake or nature for humans’ benefit? We live in an age where it is very anthropocentric, human centric, right, and humans are kind of clearly dominating with disregard of other species. Is this because it seems like this really comes up against our human centrism which is nature's there for the exploitation and benefit of humans. Are you asking for a kind of reordering of that human centrism?

Paula Ehrlich: Not at all. What I think we need is a change of consciousness that allows us to fully understand that we are part of nature, one species of many. And that we need to work together to support the species of our planet in order to inevitably support ourselves. That web of life that I alluded to that I spoke to we need to understand it we need to map the geospatial location of all the species on our planet, including ourselves at a high enough resolution to inform what places offer the most effective path forward for protection of endangered species and endangered ecosystems. And our hope is that the science of the Half-Earth Project will transform our understanding of the world and what we need to do to care for it.

Greg Dalton: When the Biden administration announced its 30 by 30 plan in January, Montana Sen. Steve Daines warned of efforts to lock up lands which will hurt Montana's farmers and ranchers and kill jobs. How do you address those fears?

Paula Ehrlich: Well, my sense is that there's no black-and-white answer that would predictably tell us that this particular kind of activity will be lost or gained as a result of focusing on conservation. In fact, in many cases current usage of land if focused or managed in the right way can sustainably support species both on the large and on the small-scale. I think the important thing is for people to have the information they need to help with their decision-making about how they manage those places and whether or not their activities would in fact cause damage or that information could be used to sustainably support their place. I mentioned our Half-Earth Project map and on that map we’ve developed something that we call a species protection index, SPI, which is kind like a FICO score for biodiversity. So, right now you can go on the Half-Earth Project map and see an SPI national report card for the protected places of every nation. You can get an SPI score from zero to a hundred depending upon how many species groups are protected in your country, and how they contribute globally to overall species protection. I’ll give you an example. So, Paraguay has an SPI that’s right around the average for most countries at about 45. And it got that score by protecting 13% of its country. Here's the thing, Ghana also protected 13% of its land but has a blockbuster SPI of almost 79. So, what does Paraguay need to do to raise its SPI and better protect the species of its place? Well, the national report cards would show where to go next, right? These places are on the map with a possible configuration of additional areas that should be priorities for protection to contribute more to the conservation of species habitat and increase SPI beyond the current protection.

Greg Dalton: That’s interesting so it’s not a one to one you can preserve a smaller land that is biodiversity rich or could be a larger amount of land that perhaps has less biodiversity. How do you define conserved land does it have to be protected wilderness area cannot be a working ranch with some conservation easement?

Paula Ehrlich: It absolutely can be and should be inclusive of ranches that are being sustainably managed or people that are earnestly creating easements on private property that can usefully contribute. In many cases, it's easy to think about large landscapes because we know they do such a good job but even smaller landscapes where they can connect create corridors for wildlife or sustainably protect particular areas of species richness or species endemism, places where those species exist nowhere else can be extraordinarily important contributions to the overall global effort to protect biodiversity.

Greg Dalton: Paula Ehrlich is CEO of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and cofounder of the Half-Earth Project. Paula, you talked about biodiversity is the next big thing after climate change. How is biodiversity loss connected to the climate emergency?

Paula Ehrlich: Well, in many ways big and small we know both that climate affects species habitat. And that shift in climate change is it affects those habitats can have an extraordinary effect on species that are already constrained by our human impact on those habitats. The climate in some ways pushes that math around what our impact is on the planet and how we need to care for it in a way that can be really difficult for us. But I think right now more and more people are realizing that if we protect the living world the species of our planet that we will also protect the nonliving world the inevitable effects of climate change. But if we just focus on the nonliving world, we may lose both. And it’s interesting to see as climate activists lean in on solutions how many of those are inevitably connected with conservation of species and ecosystems. Because they inevitably provide the foundation of support to solve the bigger problems that we’re facing with climate.

Greg Dalton: Paula Ehrlich is CEO of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and cofounder of the Half-Earth Project. Paula, thanks for coming on Climate One.

Paula Ehrlich: Thank you, Greg. It's been a real pleasure to speak with you.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about the goal to conserve 30 percent of the nation’s land and water in the next decade. This episode was underwritten in part by Resources Legacy Fund. Coming up, how the private sector can play a role in conserving land and water:

Catherine Semcer: The challenge of ecological degradation is so large and so vast this is going to take a whole of society effort. It's not something the government can solve alone. So, engaging the private sector, be it individual landowners or large institutions is gonna be absolutely critical to the success of this initiative. (:20)

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. When President Biden first announced his 30x30 plan, it drew immediate criticism from some rural parts of the country where much of the land is in farming and ranching. In states like Nebraska and Kansas, where nearly the entire state is under private ownership, some have raised concerns about where, and how, the federal government plans to set aside those acres. Climate One’s Ariana Brocious has more.

Ariana Brocious: Conservation organizations across the country have lauded President Biden’s executive order announcing his intent to conserve 30 percent of the nation's land and waters by 2030. But in Nebraska, Gov. Pete Ricketts took the opposite tact--issuing his own executive order directing state agencies to quote “resist and prevent the federal government’s attempt to usurp state authority” as they work toward the 30x30 goal. Here he is speaking to the Rural Radio Network.

RICKETTS: There are not a lot of details right now about the 30x30 plan and that’s what so concerning that the administration has announced this but has no authority to do it and has given no details about how it would be implemented.

Ariana Brocious: Ricketts went on a statewide tour, urging farmers and ranchers to be on their guard against what he called a federal land grab.

RICKETTS: Again, look at Nebraska where 97 percent of land is private, and then you put 30 percent of that into conservation, that’s really going to be devastating for our small towns and rural communities.

Ariana Brocious: That view is shared by many farmers and ranchers wary of the federal government. Kyler Millershaski is a fifth-generation wheat farmer in southwest Kansas and Vice President of the Kansas Wheat Growers Association.

MILLERSHASKI: So I think knowing how they’re going to choose the acres, what that’s going to look like. Is it going to be, yep, these acres were chosen and eminent domain they belong to the government now. That’s not going to go over too well with a bunch of farmers. Now if it’s voluntary signup that may be something folks think, I want to do.

Ariana Brocious: He says farmers already do a lot to take care of their land.

MILLERSHASKI: We care about the climate, we care about conservation. I think one of the new ones going is carbon sequestration. We’ve been doing that for a long time, we just call it soil health not carbon sequestration.

Ariana Brocious: He wants to know if acres currently in conservation programs will count towards the 30% goal. He’s put some of his acres into a local conservation program--planting grass instead of crops in the low spots of his field that flood when it rains.

MILLERSHASKI: I like it cause I can see deer, waterfowl. I’m not a big hunter but I do really enjoy seeing the wildlife out there.

Ariana Brocious: Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack has said the government will support local and federal voluntary conservation programs in line with the 30x30 goal. Yet Larkin Powell, a conservation biologist and board member of Nebraska Wildlife Society, points out the inherent tension between conservation interests and private property.

POWELL: In Nebraska if you're going to do conservation it has to happen on private land. Those private lands hold our public resources, right? The water that falls on those is what we end up drinking, the wildlife on those lands are actually publicly owned. And we all have this vested interest then in what happens on those private lands.

Ariana Brocious: Climate disruption has already affected growing seasons and increased extreme weather events. As farmers deal with increased uncertainty due to climate change, Powell says the federal push for conservation and biodiversity can offer additional support.

POWELL: The 30x30 plan gives us more impetus, that we need to be protecting more of those private lands and we need to put more public resources as in money, headed out to incentivize conservation on those private lands. So that should be a good thing for farmers.

Ariana Brocious: Powell says many farmers and ranchers rely on those federal conservation payments as a portion of their overall income. In a part of the country where so much land is in monocrop agriculture, Powell says it will be key to focus the 30x30 efforts on building large enough swaths of habitat and corridors to sustain a diverse range of species.

POWELL: Not just randomly conserving any 80 acres but thinking about, if we're going to spend money on 80 acres, where should we put that money.

Ariana Brocious: And he says he worries about the long term success of the goal and how economics in the future will play out, given past precedent.

POWELL: 10 years ago, high ethanol prices caused people to take their contract out and pay the penalty to remove it to plant corn instead of leaving land in the conservation reserve program.

Ariana Brocious: Wheat farmer Kyler Millershaski says he and other farmers hope 30x30 will use what already exists.

MILLERSHASKI: If we can expand and improve on existing programs, that will be immensely more accepted, beneficial and efficient than trying to start a whole nother program from scratch.

Ariana Brocious: Earlier this year Vilsack announced that the USDA will more directly target the conservation reserve program on climate change mitigation, rolling out new incentives and higher payment rates for farmers to encourage participation. The agency will also be investing in programs to increase the use of climate-smart agriculture. For Climate One, I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: At the beginning of this year the Biden administration announced its 30x30 plan, later dubbed America the Beautiful. I invited three guests to discuss the initiative. Catherine Semcer [sem-sir] is Research Fellow at the Property and Environment Research Center. Jennifer Norris is Deputy Secretary for Biodiversity and Habitat with the California Natural Resources Agency. And Woody Lee is Executive Director of the Utah Dine Bikeyah [dee-NEIGH bih-KAY-yah], a conservation group focused mostly on Bears Ears National Monument. In October of 2020, California Governor Newsom announced his own plan to protect 30% of California by 2030. I asked Jennifer Norris what prompted that.

Jennifer Norris: The 30x30 commitment was part of a larger nature-based solutions Executive Order really recognizing both the biodiversity crisis and the climate crisis and how important conservation was to both of those efforts. So, the Executive Order contains a lot of other important initiatives including the development of our climate smart land strategy which will help use our lands to sequester carbon and build climate resilience for example. But the 30x30 goal was really the recognition that we need to protect nature in its natural state. We need these life-support systems that support us and the best way to do that is to conserve our natural and working lands.

Greg Dalton: And how far along is it? We often hear, you know, grand visions on the future from politicians who may not be in office when that date comes. So, how far along is the plan?

Jennifer Norris: Well, what we’ve been doing this year is really developing our strategic framework for getting ourselves to 2030. So, we've had nine workshops around the state getting people involved asking them, what does conservation look like to you and your place. What are the challenges and opportunities for advancing conservation in your region? We've been diving into some key topics related to the 30x30 goal which include how do we advance equity in this space because our 30x30 goal encompasses not just biodiversity protection but also building climate resilience and improving equitable access to nature. So, we’ve been having those conversations this year and we’re developing a framework which we will finalize in February 2022.

Greg Dalton: Thank you. Catherine Semcer, Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts has called 30x30 a “landgrab.” Montana Sen. Steve Daines dismissed 30x30 as an offer to quote “lock up land which will hurt Montana's farmers and ranchers and kill jobs.” How does that prospective sit with the ranchers and farmers you're talking within rural states?

Catherine Semcer: Well, I think, you know, we really have to look at 30x30 as a coming-of-age of the conservation movement. You know as Jennifer said, this is an effort to protect the life support systems on which we all depend. And what we've seen recently is you know the US intelligence community in its most recent national threat assessment has identified ecological decline as a major danger facing the United States and that really mirrors what we've also been hearing coming out of the financial sector for some time about ecological risk and the threat of loss of ecosystems and biodiversity and what the threats they posed to business operations and the wider economy. Now diseases like COVID 19, which had its origins, you know, in wildlife is one example of those kinds of risks. You know those diseases are more likely to spill over into our population when we see things like deforestation or illicit wildlife trafficking and we've seen what they can do to the global economy. So, you know, I don't really see this as a job killer. This is something that's actually going to protect the economy by protecting the underlying goods and services that the economy depends on to thrive.

Greg Dalton: Right. And you worked previously with the Pentagon or at the Pentagon on that national security angle. You write, Catherine, that conservation is not about rolling over rural communities or leaving landowners behind to meet the demands of the politically powerful instead it's about cooperating with each other, reaching a consensus where everyone benefits. So, how much consensus building do you see actually going on this time?

Catherine Semcer: Not enough. One thing that I think we need to be doing more of both on the NGO side, the think tanks side, you know, I’m from the think tank world, but especially coming from the Biden administration with this bold ambitious initiative is to get out into the communities that are gonna be impacted. And the communities that you know are on the front lines of this risk and this danger and start talking to them and start finding out about how they see the lands that they’re currently stewarding being conserved into the future and having those conversations.

Greg Dalton: Woody Lee, a lot of the fears of 30x30 are of a top-down approach where the government dictates whose lands is whose and what can be used for. Indigenous people have a long painful shameful history of land being taken and yet the Navajo Nation has endorsed 30x30. What keeps you from fearing that this will be yet another such taking there seems to be some trust that this time is different our country is different now?

Woody Lee: Here recently there’s a bill that’s called Respect Act. And I think that might play a major role here down the road on how government to government consultation, prior informed consent will probably take its course and hopefully that particular phrase will continue to go across the country likewise and within the political arena. And we’re looking through native lens when how and why we believe that being part of this 30x30 would be in our best interest as well. So, in our society right now here on Navajo we still practice a lot of the way our traditional ways of life. And we have made a few adjustments now that we are in a drought with there’s hardly any watershed or being dry and rivers real too low and everything else. So, now we change to where we use our drip systems. And we start to use other ways of getting land back into where it will sustain itself and at the same time with our population here on Navajo is quietly increasing. So, how do we sustain our communities and still be friendly to nature. The hunt for uranium which it really paid a toll on our water system. And right now, where we are at, we can’t even drink out of our artesian well because they’re so high in heavy metals. And so, we have to do something and at the same time protect what we have and preserve it for younger generation in the future.

Greg Dalton: Catherine Semcer, in April, US Sec. of Agriculture Tom Vilsack said absolutely no land will be taken from any farm or ranch because of the 30x30 federal plan. He said he wants to incentivize farmers and ranchers to use the tools that he has at USDA to compensate farmers for being good stewards. How do you see that playing out? I heard from one land conservation person in Montana that the Biden administration is saying all the right things but on the ground it’s a different story when it gets to actual implementation?

Catherine Semcer: Well, I think this is too junior in effort at this point to really make a judgment about what's happening on the ground. With regard to what secretary Vilsack said, he’s obviously right on the mark, you know, the USDA does have a lot of programs that can benefit farmers and ranchers and increasing their stewardship. You know what I would encourage him to do though is also look at the nongovernmental partners that USDA has. There's a lot of conservation groups that the department and its agencies work with and increase access to those nongovernmental programs as well for landowners and look for ways to expand those nongovernmental programs as well as the programs that are administered to the farm bill and elsewhere.

Greg Dalton: Right. And Catherine, also, you know, the Executive Order calls for collecting input from private landowners and I wanna get Woody on this too. There’s input and there’s consultation and there’s consent. And there’s quite a debate about, you know, what is input and what is influence. So, how was that being how do you think that should play out in terms of input, yeah, when does consultation become consent and approval of these kinds of things?

Catherine Semcer: Well, you definitely need input and you definitely need consultation and you certainly need consent but most importantly, what you need is engagement. The Biden administration I would encourage them to engage the private sector as an equal partner in the 30x30 initiative. Much like climate, the challenge of ecological degradation is so large and so vast this is going to take a whole of society effort. It's not something the government can solve alone. So, engaging the private sector, be it individual landowners or large institutions is gonna be absolutely critical to the success of this initiative.

Greg Dalton: Woody Lee, you’re focused on Bears Ears which, you know, President Obama established, President Trump shrank it. Where does that stand and how does that fit into this conversation about consultation and consent?

Woody Lee: I think it all begins with a neighborly invitation from a human to human standpoint I think that’s where it needs to start from. And then from there once the invitation started then everybody is at the table and start with a clean paper and develop from there rather than having to come into a room and a document is passed upon and then everybody reacts to it. That is not an invitation to begin with and that is not a participation to begin with. Somebody had already drafted that and we have to work our way around it. So, that would be a part of where being the consultation would come in and everybody participates. So, as of now from UDB standpoint that’s where I am really adamant change and supporting the Respect Act within our government, Navajo Nation government. I’m really waving that flag and saying that, you know, we need to be at the table during the beginning of anything that’s going to affect our way of life here on Navajo or in any native lands or any native issues.

Greg Dalton: Catherine Semcer, many farmers in the Midwest are wary of federal money coming in and distorting property prices, making it even harder to farm. Do you see that as a valid concern?

Catherine Semcer: Well, you know, it’s interesting that you raise the idea of federal money and I think this is one place where the Biden administration’s plan falls a little bit short. It definitely gets off on the right foot, you know, talking about the need to conserve private lands. 60% of the United States is privately owned 75% of our wetlands are in private ownership more than 80% of our grasslands are in private ownership. So, it's essential to focus on private lands in terms of what America's conservation future looks like. Now, how do you fund it is a key question and that's where I think the White House needs to go a little bit further with its planning. And I mentioned before, the concerns of the financial sector, you know, when it comes to ecological decline the loss of biodiversity the degradation of ecosystems. And, you know, when I start looking up budgets, I see you know, Department of Interior has a roughly $12 billion budget. Department of Agriculture has $151 billion budget but of that the forest service only has about 5.3 billion. And then I look at the financial sector, and I see things like the financial biodiversity pledge, which has $10 trillion in assets under management. So, rather than focusing on federal money I think one thing we need to do is unlock the power of the private sector and really get the financial sector more involved in 30x30 in America the Beautiful in American conservation.

Greg Dalton: Jennifer Norris, what’s California's approach to that? A big state with lots of public land how much are you looking at sort of, you know, public money so to speak versus the very large financial markets that Catherine just mentioned.

Jennifer Norris: A lot of private land stewards are doing things right and we want to incentivize that and reward their contributions to biodiversity protection and addressing the climate crisis. California's actually been fairly innovative in market incentives for conservation. We started the conservation banking movement here in California where lands that are used to offset development are actually funded through private investment, they purchase those lands put an easement on them. Generally, they continue to be working lands most of them are still in grazing here in the Central Valley. And so, those sort of innovative market mechanisms are already being explored. So, I agree with Catherine I think that you know public money is not gonna be enough. We certainly though here in California we had a very big year and we’re looking to invest about $2 billion in the budget this year in the California comeback plan can be used to support our 30x30 activities. And that includes land acquisition as well as private land easement work and restoration. So, we’re pretty excited about California's opportunity to move the ball on 30x30. But at the same time, we recognize that it's, you know, at the end of the day conservation is locally driven and we want it to be voluntary so we will be partners.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about putting the 30x30 land conservation goal into practice. This is Climate One. Coming up, the necessary work of gathering input and consultation:

Jennifer Norris: You need to get out of the communities and talk to people one-on-one. And I will say that when that happens, people are really able to get amazing things done.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re exploring the how and why of President Biden’s goal to conserve 30 percent of the nation’s land and water by 2030. My guests are Catherine Semcer [sem-sir] with the Property and Environment Research Center, Jennifer Norris with the California Natural Resources Agency. And Woody Lee with Utah Dine Bikeyah [dee-NEIGH bih-KAY-yah]. Catherine Semcer recently wrote there's a backlog of 63 million acres of federal land that needs treatment to reduce wildfire risk. I asked her how the 30x30 vision is related to the frequency and intensity of wildfires that are ravaging the American west.

Catherine Semcer: When it comes to reducing wildfire risk, you know, the first thing that comes to mind are initiatives like Blue Forest Conservation in California. You know where you have elements of the financial sector working with water utilities to make sure that forests don't burn so that watersheds are protected. And this is one of those security risks that we’re really facing from ecological degradation. We've had over a century of mismanagement of many of our forest lands are now choked with fuel. While fire was a natural phenomenon historically, what we’re seeing now is unnatural because of the management have to be pursued over the past century. And when these wildfires happen, watersheds that everyone depends on for drinking water for commerce can be severely impacted. We just saw a town in Colorado turn off the taps because their water supply had been poisoned as a result of wildfire. That's not something that we can afford to have replicate over the landscape, and so as we conserve lands, we need to make sure that we’re stewarding them properly as well so that they continue to provide the goods and services that we are conserving them to provide.

Greg Dalton: You know, we’re talking about land conservation which sometimes has a sense of kind of I don’t know, putting a fence, locking some land away and that’s not the case. But there’s an underlying relationship with nature that I think informs us and we heard from some of this earlier in this episode. And Woody Lee, I noticed that your values of your organization, talk about the relationship which is not a word we often hear you often think about okay set aside some land, let it alone and all is good keep people out. So, Woody I’d like to hear how relationships with nature informs the values for Navajo Nation.

Woody Lee: You know, within our organization our main purpose is to preserve the land in the Bears Ears area. And the reason why we’re really adamant on preserving that is that is our church that’s our cathedral that our medicine cabinet that’s our food source. Within that particular small area, 1.9 million, it's all where we’re hunting our food supply our grocery store that’s our fruit source. And so, within that I think not only Navajo but other tribes that have those type of connections to Bears Ears area. So, that's why we are not closing the doors to the public we just want to educate the people that hey this is our home this is our church this is where we worship and where we heal. Going back to my younger days here within my valley in my community it was 100% traditional way of thinking traditional ways of doing things. And right now, it's upside down to where we traditionally there’s only about maybe I don’t know, 20% because the religion plays a major role in that. And now the 80% is Christian. So now, however, you know even though it's a Christian way of changing but the actual understanding of taking care of the land is still there. So, there’s layers for how diverse our community and our people has gone is making a challenging making it very challenging moving forward as a “native or traditional way” of doing things. And we’re starting to mix and be a little more diverse according to today’s world. But at the same time, those that are the 20% we do not want to blend into the world. We want to stay a different color if you will. We don't want to be where it's all blended into one color just like what the people always say that, you know, this is a melting pot of the world. We don’t want to melt in to the world we want to stay as an individual. So, within that, you know, that’s part of our preservation taking care of the land.

Greg Dalton: Or a salad bowl. In a salad bowl you can retain your identity in that salad and not melt into the cultural soup. Jennifer Norris, how much is this I’ve heard of 30x30 in California, you know, obviously setting aside land but how much of it, How much do we need to rethink our relationship with nature, as we’re trying to set aside 30% of it?

Jennifer Norris: I think that's a really crucial part of the conversation we’re having. And a lot of what motivates people to be part of 30x30 is that we are putting access to nature and all of its benefits for all of California at the center of what we're trying to accomplish. We recognize that there are communities that don't have access to green spaces, you know, the COVID lockdowns, a lot of people couldn't go more than a couple miles from their house. And for some, that meant they had no place to walk. They had no access to nature at all. And that's unacceptable. You know, we need to find ways to ensure everyone has the sort of life-affirming benefits of being part of nature but also the health benefits. Trees and cities are beneficial for extreme heat and keep our air clean.

Greg Dalton: Jennifer Norris, Western states already have large tracts of federal lands National Parks, National Forest, etc. Imagine a lot of the land additional land to be conserved in California might be in those areas. People already resent the portion of land and federal control. So, how is that gonna be the balance that kind of I guess the of the politics of that, you know, more land over under government control in some very rural and conservative parts of California.

Jennifer Norris: I think as I said, you know we’re really interested in all of the above strategy. There are certainly opportunities to expand federal conservation, but I think the private sector, as Catherine has pointed out, you know, there's just a lot of really important landscapes that are in private lands and we need to partner with private landholders to incentivize their conservation and the good work that they already do.

Greg Dalton: Does that run the risk of one of the criticisms of some of the carbon offset programs is that landowners often very wealthy are getting paid through the cap and trade and offset programs to do things they were already planning to do. So, it’s like free money in your pocket is that a potential risk for some of these you said these private landowners are good stewards. Are they gonna be then paid to do what they're already doing with taxpayer money?

Jennifer Norris: Well, I think if we get long-term commitments to maintain natural lands and their good condition, I think that should be compensated. I think that other people, you know, we all benefit from that land stewardship and if there is a loss of revenue that's associated with that, I think that’s something that we should all share. So, I think it's to our benefit to build those partnerships.

Greg Dalton: Catherine, you’ve written that or noted that federal conservation efforts of the past have fueled resentment of the government to the point of violent extremism when that level of distrust is already so pervasive, what hope do you have that that public-private partnerships can happen and not fuel some of the extreme reactions we’ve seen in Oregon and other places?

Catherine Semcer: Well, this is where engagement and early engagement really comes into play. Those who are supporting the 30x30 initiative, especially those in government need to get into these communities be speaking with these individuals who own this land to make sure that they are very clear about what the intent here. The intent is not to take away anybody's private property. The intent is not to restrict anybody's economic activity. The intent is to reward good stewardship and continue providing the goods and services our economy needs to thrive. And I think if we do that then we get ahead of the conspiracy theories and the other things that violent extremists will often take advantage of in order to get a hold of the community.

Greg Dalton: So, suppose the three of you were tasked with implementing 30x30 across the United States, what would you if you had a magic wand for making this happen pretty ambitious, I guess we should get a baseline here that I don’t know something like 12% of land is conserved now. We’re trying to get to 30 in a decade. I've read that the percentage of protected waters is higher and I’ve been remiss in mentioning this also applies to water, streams and I think even and perhaps even oceans. So, suppose, Jennifer let’s start with you, sort of you had that magic wand what would 30x30 implementation look like for land and water?

Jennifer Norris: Well, I think in California we’re doing it right. A lot of what Catherine and Woody have both been calling for is really how we’re trying to approach this is to establish the framework, identify the strategies that are successful, look at supporting those. But at the end of the day as Woody said, you know, it's a neighborly conversation. That's how this implementation really works. And so, you need to get out of the communities and talk to people one-on-one. And I will say that when that happens, people are really able to get amazing things done. I've seen it happen in my experience here in California working with lots of people on the ground. They want to take care of the land and they want to partner with you to make a difference. And so, you know, it's difficult I think when you think about the whole country where do you begin. And so, you know, the Biden administration has put out their framework and their approach and now the next step really is to engage with those communities across the country and really figure out at the local level, you know, what are the priorities. What are the obstacles and how do we overcome those together?

Greg Dalton: Woody, let’s get you, that America the Beautiful plan has pillars that sound good, local-led, honor tribal sovereignty, honor private property rights use science as a guide. How would you like to see 30x30 roll out, Woody?

Woody Lee: I think first thing that needs to be done is put everything on the table under lessons learned through history. Now, based on that I think we can make a directional where we should be heading forward as all people here within our country. And then see if we can be neighbors according to that from lessons learned.

Greg Dalton: Well, that's a very painful history, Woody, frankly that a lot of Americans willfully forget or never learned in the first place. Looking at histories pretty painful, it's not pretty. I mean I don’t need to tell you that it’s a lot of people, lot of people don’t like to look at stolen lands, stolen labor.

Woody Lee: When Sec. Haaland first visited our area here several months ago, I mentioned to her that a lot of the trauma is still within a lot of native people. Those that’s actually gone to boarding schools. And from there, a couple months later, you know, how that boarding school has been exposed across the country and into Canada. And so, there are many just like you’re saying there’s a whole bunch of stuff that we have endured and those are lessons learned. And we tell our kids, you know, this is the history that we have. You will not hear or read this in any college books that, you know, it may have a paragraph here and there and there's nothing really that will draw the picture of what has really happened. So, we fill in those gaps with our kids and grandkids in our native languages and in our native thought in the way we think which is totally different than basically everyday academic lens. And so, in that sense our kids are really learning that particular portion of that.

Greg Dalton: Catherine Semcer your ideas on how 30x30 could roll out if you could have your magic wand, what would like to see to achieve this ambitious goal in nine years?

Catherine Semcer: What I would add is two things. First, in Washington DC personnel is policy and how the Biden administration staffs up interior and agriculture is gonna make a big difference about whether this initiative succeeds or fails. And I would encourage them to maybe look beyond sort of the traditional appointments in terms of conservation and look to the people who have experience doing what Jennifer and Woody just laid out so that they can get out there and hit the ground running. Because you know, we’re behind the curve on this. And then second, you know, in addition to rethinking our relationship with nature I think we also need to rethink our institutions. You know, whether they're public or private, most of our conservation organizations were established and given their missions in a different climate than the one that we have now, and certainly a different climate than the one that we’re going to have in the future. So, we really need to do some serious thinking at the institutional level about what we want the jobs of both agencies and NGOs to be going forward.

Greg Dalton: Woody Lee, as we wrap up, we’ve been talking about land and I wanna make sure before we wrap up here that we touch on water because rivers are the lifeblood of ecosystems and oceans often get overlooked.

Woody Lee: Right now, from a nation standpoint here on Navajo, we are on a Navajo reservation which a lot of the things that we do every day depends on whether or not it is okay with BIA or the federal government. Now in this instance we’re gonna speak of water. We cannot actually build dams to recharge our watershed. Those are some of the policies that was meant policies were mentioned that really deters us from self-sustaining ways of thinking. We would like building watersheds or how do we recharge that and start building up small dams and getting those waters and we just can’t do that. So, in that sense, you know, those types of strings that needs to be changed and to where 30x30 would make a difference of how the government is denying us of taking care of our own land by denying us of certain access and certain ways of doing things to advance our ways of thinking of taking care of the land.

Greg Dalton: Our thanks to Woody Lee, Jennifer Norris and Catherine Semcer for talking with us today on Climate One about the 30x30 ambitious plan to set aside 30% of America’s lands and waters in the next decade. Thank you for coming on Climate One and sharing your insights.

Jennifer Norris: Thanks for having us.

Catherine Semcer: Thank you.

Woody Lee: My pleasure.

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast on your favorite app. Talking about climate can be awkward and difficult. Sometimes it can be a conversation killer. But we need to talk about climate to understand and address it. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help open up the climate conversation.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Ariana Brocious is our producer and audio editor. Our audio engineer is Arnav Gupta. Our team also includes Steve Fox, Kelli Pennington, and Tyler Reed. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.