Banking on Change at Standing Rock

Guests

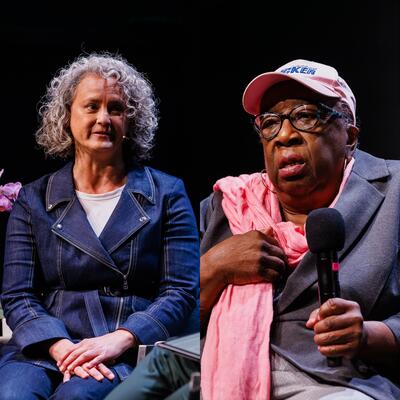

Lynn Doan

L. Frank Manriquez

Pennie Opal Plant

Summary

They were an unlikely group of activists; Native American youths concerned about teen suicide sparked the movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL)—a movement which ultimately spread across the country. Veterans and others joined in, traveling to the construction site and showing solidarity with activists. Protesters objected to the $3.8 billion pipeline route, which they say threatens freshwater supplies and disrespects ancestral lands.

Guests:

Pennie Opal Plant, Co-founder, Idle No More SF Bay

L. Frank Manriquez, Indigenous California artist and activist

Lynn Doan, Bloomberg News

This program was recorded live at The Commonwealth Club in San Francisco on May 11, 2017.

Full Transcript

Announcer: Climate One is changing the conversation about energy, economy and the environment.

On June 1, oil began flowing through the Dakota Access Pipeline. But demonstrations at the Standing Rock reservation in 2016 made national headlines, and galvanized a movement to resist other fossil fuel projects.

Join your host Greg Dalton for the next Climate One.

Announcer: This is Climate One, changing the conversation about energy, economy and the environment.

In 2016, opposition to the Dakota Access pipleline made national headlines and galvanized a movement.

POP: There were things that happened at Standing Rock that were so powerful… Just one of those really big potent moment of ‘we can do this.’

Announcer: Native American water protectors and their allies faced tear gas, rubber bullets and water cannons.

LFM: We swore to protect and defend against foreign and domestic and this is about as domestic as it gets.

Announcer: But the effects of the resistance didn’t end there.

LD: While Dakota Access was being fought, there was a whole other set of energy infrastructure projects that were coming up against the same kind of confrontation.

Announcer: Banking on Change at Standing Rock. Up next on Climate One.

Announcer: What’s next for the resistance inspired by Standing Rock? Welcome to Climate One – changing the conversation about America’s energy, economy and environment. I’m Devon Strolovitch. Climate One conversations – with oil companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats – are recorded before a live audience and hosted by Greg Dalton.

The Standing Rock Sioux and other tribes say the $3.8 billion Dakota Access Pipeline across the reservation threatens their water supplies and will hurt sacred sites and culturally important landscapes. The company that built it says it will deliver jobs and support energy independence. Demonstrations gradually emerged at Standing Rock in 2016 and made national headlines when police used tear gas, rubber bullets and water cannons on demonstrators. That prompted an estimated 4,000 U.S. military veterans to go to Standing Rock in the dead of winter to serve as a human shield for the people opposing the pipeline. While they were there, the Army Corps of Engineers announced it would seek an alternative route, but Donald Trump reversed that decision early in his presidency, and oil began flowing through pipeline on June 1. On today’s program, we’ll discuss indigenous rights, news coverage of energy protests, and anti-oil activists praying for people who work on oil pipelines and refineries.

Lynn Doan leads the coverage of oil and gas in the Americas for Bloomberg News. She manages a team of reporters who wrote about Standing Rock and are now covering other controversial pipelines. L. Frank Manriquez is an indigenous artist and activist. She's involved in the preservation and revival of native Californian languages through traditional arts practices and conferences. She went to Standing Rock three times. And Pennie Opal Plant is co-founder of Idle No More SF Bay, an organization that stands for the rights of indigenous people, Mother Earth and the sacred system of life.

Here’s our conversation about power, confrontation, and forgiveness at Standing Rock.

Greg Dalton: Pennie Opal Plant, let’s begin with you and tell us when you first saw a field where fracking was taking place.

Pennie Opal Plant: It was in North Dakota during the Extreme Energy Summit and I was on Candy Mosset's territory. That one looked very innocuous in North Dakota. They were in the middle of fields and the structure was not tall and imposing. The first one that I saw was very contained. It was painted green and it didn't have the leaked fracking fluid like the ones that I witnessed in Ponca, Oklahoma which were so toxic that you could barely stand next to them and two people that were with me had to get back in the car. And we also witnessed the spills where all of the grass was dead and the spills that had gone into the creeks and the river. In North Dakota on every hillside where we were from miles and miles, maybe not every hillside but hundreds of them, they had that the flares going up from the fracking wells. You can see them everywhere at night like burning stars on the horizon. And the other thing that I witnessed that was pretty horrifying were the man camps. You know, wherever these big fossil fuel projects go in they have man camps and there are temporary structures like FEMA trailers where they bring men in from all over the world. There were men there from Africa and different parts of the world that were brought in. And in some of these man camps, I would say most of them there is high levels of drugs that have been brought into the communities where the indigenous people whose communities these are on have to deal with rising rates of drug abuse among their own teenagers and young adults. There's one documented case in North Dakota where a four-year-old little girl was raped over and over again in one of these man camps and she escaped running and screaming through the streets. And we’re not just talking about violations to Mother Earth. We’re also talking about the connection between women and Mother Earth that cannot be broken. And that's what we see with these man camps in these areas.

Greg Dalton: L. Frank Manriquez, when you went to Standing Rock you witness some tension in these camps. So tell us about the first time you went there, in fact you broke up some fights there.

L. Frank Manriquez: Oh the tension? You had anywhere from a thousand to 15,000 people living in one space at any given time with no rules, no rhyme, no reason as to the organization of camping there was no running water, no place to bathe, no place really to as we know it, you know, to survive. It was living on the plains and there was a lot of tension because the DAPL Army was surrounding us all the time you couldn’t go for a walk because they would snipe you, you know, or kidnap you, keep you for a few hours. They didn’t let you sleep because they put big lights, huge lights that they would shine on the camp and then they flew an airplane or a helicopter over the camp all night long spraying. So that put a little tension. And then there was the tension of patriarchy which that's where I became an enforcer.

Greg Dalton: And what did you do to push back against that patriarchy?

L. Frank Manriquez: Well, I followed what an elder asked me to do, which is the way that we are supposed to behave. I pulled into camp and I found, like I said I felt the vibe of this camp and it happened to be the camp where the first baby was born at Standing Rock and where the eagle had landed. And so I'm not out of the car five minutes when the grandmother comes out and asks me to remove those men from this woman’s space. You know it’s a small space they didn't have to be there. There was a whole other plain that they could've gone to, but it was beyond that particular camp. I found that there were rapes in camp, you know, some they thought that DAPL snuck in and, you know, it’s a –

Greg Dalton: DAPL, Dakota Access Pipeline.

L. Frank Manriquez: The DAPL Army, they’d come in and, you know, maybe rape people, to terrorize us, because there are all these terrorizing tactics, you know. They tried to set us on fire a couple of times but creator took care of that, sent the wind the other way and they burnt up but, you know, you get what you launched I guess.

Greg Dalton: Lynn Doan, you were covering this. When did you realize that Standing Rock was a national story?

Lynn Doan: I think actually one of the biggest regrets that I had in when we decided to start covering this was how late we decided to start writing on it. It went from what a few hundred to a few thousand. And then I just remember that day when I was getting an email every two hours from somebody at Bloomberg News saying, “Hey, do you know about this pipeline? Are you covering this protest because my friend just drove by and there are thousands of people out there protesting.” And that was the day when we decided, okay, now it has an impact on the company, now it has an impact on markets. There are tens of thousands of protesters that are coming out to this one spot trying to halt this pipeline. That’s when we made the decision that it was a national story to start covering.

Greg Dalton: So if it affected a small group of Native Americans it didn't matter as much but when it got to your friends it did?

Lynn Doan: I wouldn’t say that it didn't matter as much. I would say that Bloomberg News is focused on covering the finance and business and markets aspect of news. And so once something reaches a magnitude that's going to affect those spaces then we jump on it.

Greg Dalton: There was a lot of checking in on Facebook, use of social media, and there was reports of the police were using social media to track people. And then I remember a day when everybody checked in at the Dakota Access Pipeline and they were all over the country and they were not really there, but they wanted to create the perception or confusion that they were there. But Lynn Doan, the head of the company that's building the Dakota Access Pipeline, Kelcy Warren said that he underestimated social media. Tell us about that.

Lynn Doan: That’s right. On an analyst call I believe it was his fourth quarter earnings call. He had to speak to analysts about what happened with the protests at Dakota Access. And I mean even for the media outlets on the national scale that were covering this it seemingly happened overnight, it was so rapid. And the social media aspect of it I think we can say just based on our reporting really drove that to the point where when asked how it happened and what could've been different, Kelcy Warren, the head of Energy Transfer got on that call and said, we tried everything and followed every protocol that we thought that we should and it still turned into his word, a “mess.” And what he said was that he felt as if the company and himself had underestimated the power of social media and how that could affect the number of people that were involved in these protests.

Greg Dalton: L. Frank.

L. Frank Manriquez: I’d like to change something and that is I was not a protester. I am a protector. We were not protesting. We were protecting. It wasn't Indian trinkets and our wells, it’s 17 million people. We are doing what is mandated from creator creation that we protect. And it was the social media that drove everything and it was creator creation that drove the social media because it was a call from the young people and the women to show up, and we did. And then the social media got big, but first we came.

Greg Dalton: Lynn Doan, there's a lot there in terms of, you know, someone's either a freedom fighter or a guerilla or a protester. There's a lot of embedded in the language that we in the media use. I’d like to hear your thoughts on that which he just called me out on maybe, you know –

Lynn Doan: It’s funny because I had that written down – protester versus protector – as one of the messages that was clearly trying to be delivered by the people that were part of the opposition. And I think that it was heard loud and clear even if the media use the word protester that the opposition there was looking for a peaceful approach to fighting this pipeline. The day that the Army Corps in February decided to issue that permit to allow Energy Transfer to finish that line underneath the lake, I remember it broke at about noon our time in San Francisco and we got the headlines out, we got the story out and then we’re kind of just waiting for that reaction from Standing Rock and from the group that represented the Native Americans. And it wasn't until three hours later that after the news broke that we finally got a statement and the statement was about how disappointed they were and how they were going to fight it. But it offered no context as to, you know, were there talks, were there negotiations, did talks break down. The next day, we received a statement from Standing Rock, a second one that was much more retrospective. And they explained in the statement that the reason why there was a delay in response was because Dave Archambault, the chair of Standing Rock was actually in flight to Washington at the time for a meeting that he thought was going to be a sit down with members of the Trump administration so that they could talk about the concerns that the Native Americans had with the project moving forward. And that it wasn't until he landed that he had found out that the Army Corps had issued the permit and then just canceled the meeting and headed home. I think that from all of those statements it's clear that the message that the opposition was trying to send was we tried to talk, we tried to tell them our concerns and we tried to do this in a peaceful way.

I think it is important to note, however, because as a reporter I don't stand on either side of this that we also reported on Energy Transfer talking about the things that were happening at the camp to their own employees. And so, you know, we covered the executive for Dakota Access that filed testimony at a house committee meeting shortly after the Army Corps issued that permit in which they likened some of the opposition to terrorists. And he cited a few examples in which some people had broken into pump stations and had forcibly shot the pump stations and how some employees and their families had received death threats. So we’ve been reporting both sides of that.

Greg Dalton: Pennie Opal Plant, is there some truth to that, that there are also some that kind of aggressive and appropriate behavior on the side of the people against the pipeline?

Pennie Opal Plant: I don't know. I would tend to believe that that answer would be no to that because at Standing Rock there were prayers that were laid down hundreds of years ago for this time right now. And as indigenous people, we understand that the time that we’re in right now is a time of deep prophecy. The Keystone Pipeline, the Dakota Access Pipeline all of these other pipelines, you know, that are trying to be permitted to run through this country were foreseen hundreds of years ago, you know, that’s why it's called the black snake. So for indigenous people the understanding is that our power is our prayer. I’m sure that there are young warriors that are, you know, full of energy and full of the desire to just make the harms to the earth, air, water and soil stop. But I don't know that anyone of them would actually go against the will of the holy people and the spiritual leaders and the elders and threaten pipeline workers. I mean I don't know of anyone that would do that.

Announcer: We’re hearing about power, confrontation, and forgiveness at Standing Rock. This is Climate One. You can subscribe to our podcast at our website: climateone.org. Greg Dalton will continue his conversation in just a moment.

Announcer: We continue now with Climate One. Greg Dalton is talking about power, confrontation, and forgiveness at Standing Rock with Bloomberg energy reporter Lynn Doan. Indigenous artist and activist L. Frank Manriquez, and Idle No More SF Bay founder Pennie Opal Plant.

Here’s your host, Greg Dalton.

Greg Dalton: I’d like to talk L. Frank Manriquez about the impacts, the health impacts that you feel now having been at Standing Rock.

L. Frank Manriquez: Right. I’ll start kind of in the middle. Because I am ill I've gone to my Indian health clinic where they say, “Well, you've been poisoned by what we don't know and that could be so broad and we don't know what happened.” So my doctor suggested I start a Standing Rock health survey, which is available online and it's anonymous, you don’t have to tell who you are and where you live and all that. But it asks a variety of simple questions how long were you there at Standing Rock? Did you go to the frontline? What was your experience? We have one chart that says your health rate it before Standing Rock and the bar graph shows on the healthy end that the bars are quite tall. And then after Standing Rock that’s flipped over those high bars are now all at the other side of the graph on the side that they’re all ill. And what some of them are experiencing are when they cough, they bleed from orifices. I, myself have camp cough or restricted chest where I can't really breathe very well. They flew planes over us that crop dusted us with we don't know what. Someone has been tested for Rozol, it’s supposed to kill the prairie dogs. Some 40,000 pounds was spread on the camp on the surface. So then you have the bullet holes and the canisters to the eyes and when they would grab you they would urinate on your sacred things like your eagle feathers and they would break them and they would stomp on feet and break them. And things were reaching a pitch level with the DAPL Army, they all had guns, we had nothing but prayer. And they would shoot us anyway and I would hear the elder say, “Everyone back up, stop.” I live through the 60s I've never seen a riot stop because an old person said back up. But what they did, Martin County Sheriff at one point said, and this I think relates to health is they allowed the ranchers to shoot us if we frighten them. So the preponderance of the surveys have a great deal of PTSD symptoms on them. And, you know, because a lot of magic happen there and people were useful no matter their skill level of about anything. And when you left, you were no longer that useful out here. So people coming back have this PTSD that their families don’t understand, we’ve been at war. We've had people with guns shooting us, we've had airplane circling over us, you know, we've been at war and so our families don't quite know how to embrace this. And we don't know how to re-embrace them because we've changed.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about the Dakota Access Pipeline the violent confrontation there and forgiveness. There was a powerful moment in December of 2016 when Wesley Clark Jr. knelt before Dakota medicine man, Leonard Crow Dog and asked for forgiveness for the atrocities carried out by the United States military. Let's listen.

[Start Clip]

Wesley Clark Jr.: We came here to be the conscience of the nation. And within that conscience we must first confess our sins to you. Because many of us, we particularly are from the units that have hurt you over many years. We came, we fought you, we took your land. We signed treaties that we broke. We stole minerals from your sacred hills. We blasted the faces of our presidents on to your sacred mountain. And we took still more land. And then we took your children and then we try to take your language. And we tried to eliminate your language that god gave you and that the creator gave you. We didn’t respect you. We polluted your earth. We’ve hurt you in so many ways. And we’ve come to say that we are sorry. We’re at your service and we thank you for your forgiveness.

[End Clip]

Greg Dalton: That was Wesley Clark Jr. son of former presidential candidate General Wesley Clark. Pennie Opal Plant, I’d like to have your reaction to what he did. He knelt down before that medicine man. Tell us about the ceremony and the importance or your reaction to that.

Pennie Opal Plant: My husband is a Vietnam veteran. And when we saw that, when we saw the veterans going in and what they were saying that, you know, they’ve been in wars where they were fighting people over resources around the world. And they came home and saw this thing happening in their own backyard. And my husband talked to me many times about going to Vietnam and as a native man and seeing, you know, being told to make war on these brown people that looked more like us than not. And so it was very emotional for both of us when we saw the veterans come in. And it was just another sign in this time that we’re living in is so potent with prophecy and signs of where we are right now. And so I think for my husband and I it was that and the apology, not only of all the atrocities that the United States government has perpetrated among indigenous people, but also the apologies for the doctrine of discovery which was also burned there, which the doctrine of discovery gave the Royals in Europe permission to come here and other places around the world and rape and pillage and steal continents literally. And so there were things that happened at Standing Rock that were so powerful and such powerful indicators of how the world is beginning to shift away from a system of capitalism that truly only works in an infinite system and we live on a finite planet. So capitalism it does not work on a finite planet. It is also a fairly new system it's, you know, under 300 years old, where we have existed for well over 100,000 years as human beings in this form on Mother Earth's belly. And so I think when the veterans came in it was just one of those really big potent moments of “We can do this. We can work together to inspire people to stand up with all the love in our hearts for everything that we hold dear, for the earth, the water, the air and the soil and just what we need the basic things that we need to simply exist and ensure that those qualities of this planet can continue to exist so that future generations can live at least as close to what we've enjoyed in our lifetimes.”

Greg Dalton: L. Frank Manriquez, your response to the apology from Wesley Clark Jr.

L. Frank Manriquez: That whole day was just incredible. It was beyond, you know, a lot of people in camp put it down. A lot of Indians have animosity towards the military, I don't know why. And they were really cursing them out but as you said, you know, and as I told the kids because the kids are saying, well, these people have gone over and fight for oil, you know. And I said, well what side are they standing on now, you know, who are they standing with right now and what are they saying. And when they made that apology, those elders, it wasn't just that Indian doctor, it was all these elders. That one woman who got that electoral vote, she was one of the women there. And they accepted that apology. I mean you gotta start somewhere with some healing. Inside this is a, what I’m holding is a scarf that, it’s just a scarf that the high school kids at Standing Rock made for us vets when we came in. But wrapped inside is an eagle feather, piece of an eagle feather. They gave those soldiers this eagle feather and they cradled that eagle feather like it was a newborn baby. They couldn't take their eyes off of it. And there are this big burly Army guys, there were a few women but mostly it was dudes and telling us what to do, alright, okay. Not really, don’t try it. So, they were holding those eagle feathers and, you know, I keep telling my friends that to a soldier, a decoration they understand what a decoration is. And to receive these eagle feathers and to receive that forgiveness, a lot of them now well, now they're all speaking Lakota. “Mni Wiconi” water is life. They’ve gone to Flint, Michigan. They've gone to other places, you know, but we couldn't stand it when our own people, you know, we swore to protect and defend against foreign and domestic and this is about as domestic as it gets. We may not be domesticated but we, you know, we’re pretty well domestic. But what happened when the military came was nothing short of a miracle for the military because these people are going to go back out and talk to their friends who are not going to understand why they even went. And it was life-changing and one of the strongest, most potent things. I think that blizzard was held just to hold the Indians and the Cowboys in the same room so they could work it out.

Greg Dalton: L. Frank Manriquez is a protector of native California culture and we’re talking at Climate One about the Dakota Access Pipeline. Also have Lynn Doan from Bloomberg News and Pennie Opal Plant. I'm Greg Dalton. Pennie Opal Plant, there was a protest around the Army Corps of Engineers office in San Francisco protesting because they were in charge, had a role in this pipeline and you went in to see the colonel. Tell us that story.

Pennie Opal Plant: So Idle No More SF Bay organized two very large actions at the Army Corps of Engineers on Market Street in San Francisco. And each one had over 5,000 people at it and it was during the week so it was that kind of commitment that people had to not go to work that day or, you know, I’m self-employed, I own a business so I had to pay people to be at my business. So I wasn't there. And the first time we were invited up because we were mic checking up on the fifth floor where the Army Corps offices are from the outside. And what we were mic checking at the top was “we’re not going away, we’re going to stay here forever.” And it was, you know, we were saying it metaphorically, like Indian people are not going away. We've always been here, we’re going to continue to be here you can't make us go away. Well, I think they took that literally and they sent someone down. And so three of us went in the first time and it was very informative. It was outrageous to me how much they didn't know. The dog attacks that just happened that sacred site where DAPL had jumped ahead 15 to 20 miles to destroy a recently acknowledged sacred site had just happened. And they didn't know anything about that. They didn't know at that time there were over 200 Indian nations sovereign nations that had sent supplies and solidarity letters and busloads of people there to the camps. It was astounding what that they didn't know. So that was the first meeting and I am compulsively inclusive. I've always been like that. I take that whole we’re all related thing very seriously. And so when we left, I hugged everyone except for the really big homeland security guy who is like not he was very clearly not huggable. So I just patted him on the shoulder. So the second time when we had the big action there, they sent someone down to find me. And a friend of mine an NLG attorney was next to me and so we went in and each time there was the colonel, the attorney, the public relations person, the homeland security guy. I think I’m forgetting someone. Anyway, when we sat down at the table, Colonel McFadden looked at me and he said, “Pennie, before we start will you lead us in a prayer?” And I said, “Sure” and so we stood up and held hands and prayed together. And we prayed for, you know, we prayed for the water protectors and we prayed for Martin County Sheriff to remember how to be a real human being, and for their minds to be clear and their hearts to be open. And then we prayed for all the people along the pipeline and the fossil fuel industry executives to become aware of what they're doing to the system of life that we need to simply exist. And we prayed for their families of the people who were in the room and what that told me is that we truly are all human beings, I mean even the people that some people consider to be our enemies, they are part of our human family. And I believe that most human beings want clean air, clean water, clean soil and a vibrantly healthy future for their children and those to come. And so because of that I personally don't have a human enemy. So I have walked into, you know, these oil lease auctions in New Orleans, where they're full of fossil fuel executives and spoken with fossil fuel executives. And, you know, asked them do you have kids and, you know, just talked to them like people. I asked them if they knew about Mark Jacobson's work at The Solutions Project and, you know, just to have conversations because I'm sure that they want the best for their children and the children to come and their own families. You know, I feel like I have these pom-poms for Mother Earth. And I don't care who it is that standing in front of me I'm just gonna come at them with that because that's all I have. And that always opens the door because who doesn't have a child in their life, a neighbor, a niece and nephew, somebody a child that they love. And that's how I open the door.

Greg Dalton: Lynn Doan, let's talk about that shift, that transition. You cover for a very important news organization. Oil and gas have these encounters had an impact on the companies or the markets?

Lynn Doan: That's a good question. I think you can probably answer that two ways. One is yes, absolutely there is a quantifiable impact. You can do some simple math just on Dakota Access. This is a 500,000 barrel a day pipeline that was supposed to come into service in 2016. We’re now in 2017 and five months in the 2017 they're still preparing to put that into service as of June 1st. So that’s 500,000 barrels. Bakken crude is probably trading at somewhere around $47, $48 a barrel. So that right there is almost $25 million worth of oil that's supposed to be flowing through this line right now, so that's real money. I think the other answer is more difficult to quantify, which is the broader industry impact that this site is inevitably going to have on future fights against controversial energy infrastructure. And I think what’s important to note there is that while Dakota Access was being fought, there was a whole other set of energy infrastructure projects that were coming up against the same kind of confrontation. I mean very targeted, personalized attacks. And so we as a team we’re already interviewing analysts and banks on Wall Street about this and how it was changing the conversation. And I can tell you that even then the discussion was already shifting from what pipelines or projects do we put our money in that are going to lay brand-new shiny lines through lands that have yet been touched to where do we put our money into existing pipelines where we are retrofitting those or expanding those, those projects aren’t going to get as much backlash, right. So that kind of impact I think still remains to be seen.

Announcer: You're listening to a Climate One conversation about power, confrontation, and forgiveness at Standing Rock. You can check out our podcast at our website: climate one dot org. Greg Dalton will be back with his guests in just a moment.

Announcer: You’re listening to Climate One. Greg Dalton is talking about power, confrontation, and forgiveness at Standing Rock with Bloomberg energy reporter Lynn Doan. Indigenous artist and activist L. Frank Manriquez. Idle No More SF Bay founder Pennie Opal Plant.

Here’s Greg.

Greg Dalton: We’re gonna go to our lightning round where I’ll mention a noun and ask our guests to name the first thing that comes to their mind, unfiltered. Starting with Pennie Opal Plant: Barack Obama.

Pennie Opal Plant: Yeah, just another guy sitting in the chair.

Greg Dalton: L. Frank Manriquez, former U.S. Interior Secretary Sally Jewell.

L. Frank Manriquez: Just another gal sitting in a chair.

[Laughter]

Lynn Doan: I think I know my answer is gonna be just like.

Greg Dalton: Lynn Doan, current Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke.

Lynn Doan: Perhaps more fossil fuel friendly.

Greg Dalton: L. Frank Manriquez, Standing Rock Sioux Chairman David Archambault.

L. Frank Manriquez: DAPL Dave.

Greg Dalton: Pennie Opal Plant, President Andrew Jackson.

Pennie Opal Plant: Oh, murderous, genocidal maniac killer.

Lynn Doan: It sounds like she was prepped for that one.

Pennie Opal Plant: Always.

Greg Dalton: Lynn Doan, Kelcy Warren CEO of Energy Transfer Partners the company building the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Lynn Doan: Billionaire pipeline magnate. That’s usually what we describe him as.

Greg Dalton: True or false, Pennie Opal Plant. Some Caucasian people don't like to think about what their ancestors did the first nations because they feel guilty about it?

Pennie Opal Plant: Get over it.

Greg Dalton: Lynn Doan, financial markets incentivize profits above everything else?

Lynn Doan: False.

Greg Dalton: L. Frank Manriquez, when you were invited to come here today you thought you would be entering a bastion of white privilege?

L. Frank Manriquez: Yes.

Greg Dalton: Pennie Opal Plant, bringing oil to the San Francisco Bay Area via a new pipeline would be safer for humans and the environment than ships or railcars that currently bring that oil here now?

Pennie Opal Plant: It’s time to completely transition off of fossil fuels and no new infrastructure projects.

Greg Dalton: L. Frank Manriquez, villainization of people who work in fossil fuel companies is an effective strategy for moving the country off of fossil fuels?

L. Frank Manriquez: No.

Greg Dalton: Last one, Lynn Doan, when you go into the office tomorrow you're going to assign your team of oil and gas reporters at Bloomberg a big story on the flow of love?

[Laughter]

Lynn Doan: If love can move markets, affect business or finance, maybe.

Greg Dalton: Good answer. Let’s give them a round for getting through that.

[Applause]

Pennie Opal Plant: I’ll invest in that.

Greg Dalton: Pennie Opal Plant, where does this go now the Dakota Access Pipeline it's in court, maybe it could slow down maybe it gets completed. Where’s the big picture going forward?

Pennie Opal Plant: The big picture is that the water protectors that were at Standing Rock are saying that Standing Rock is everywhere. And of course it is everywhere because all of the waterways and air. I mean I have, I'm a signer of the Indigenous Women of the Americas Defending Mother Earth Treaty. And there are signatories of this treaty in the Amazon and in Alaska and at the tar sands and at a lot of these big fossil fuel projects on indigenous territories. And we get crude from the Amazon, from the heartland of the lungs of Mother Earth. And so I think for anyone listening to this show that if you look at your own area like what's being threatened here and by whom and what can I and my family and friends do about that. And that has been the message from all of the water protectors at Standing Rock. Standing Rock is everywhere, it’s not just in the United States, it is around the world and we have a responsibility to making sure that the future is safe for not only human generations to come but the rest of our nonhuman relatives.

Greg Dalton: Lynn Doan, if a, you know, a drop of oil spills out of Dakota Access Line, it gets covered. Is it gonna be more coverage of these things whether there are demonstrations, et cetera, pipeline resistance going forward because, well, Keystone and Standing Rock have put them on the map or are they just gonna be no longer news anymore because they happen all the time?

Lynn Doan: There's no doubt that it raised the level of coverage of pipeline spills overall. I can give you one example right now. The same company, Energy Transfer, that built the Dakota Access Pipeline is also building a natural gas pipeline known as Rover in the eastern U.S. And not too long ago, we actually broke the news on the fact that Energy Transfer had reported to federal regulators that they had just billed 50,000 barrels of drilling fluids while constructing that Rover pipeline. And, I mean, perhaps we would've written about it anyway because 50,000 barrels is a lot of spillage. But the context there really informed that story the fact that it was the same company that had developed Dakota Access and the fact that there was also opposition to Rover even before the spill happened. And the fact that this is just the latest woe, the latest development in this ongoing story definitely elevated it.

Greg Dalton: We’re gonna go to our audience questions. Welcome to Climate One.

Male Participant: Thanks. Hi. My name is Hunter Franks. This questions is for either Pennie or Lynn. I wonder if you could talk a bit about the divestment campaigns that have happened as a result of Standing Rock either financially or otherwise. I know there's been a couple cities that have divested, but curious if you have any updates on that.

Greg Dalton: Before we go to that question, we actually interviewed a professor at UCLA, Professor Ivo Welch. He spoke to us about the divestment campaigns. He thinks there are better alternatives to making real change. Let's listen.

[Start Clip]

Ivo Welch: My name is Ivo Welch. I am the J. Fred Weston Professor of Finance and Economics at UCLA. I think what one should learn from our research is that embargos and boycotts are likely to work only if there are few alternatives. So if I were, say the city of Santa Monica and I was asking myself will our taking out the money cause the CEO of Wells Fargo lose any sleep. The answer is probably no. It is not like Wells Fargo is earning a large amount of its profits by dealing with Santa Monica or anybody else in particular. The other problem with embargo is that they give one the feeling of success as if something is accomplished and that actually distracts from other activities that might be more productive. So if I was interested in stopping the Dakota Pipeline I would probably try and sue in court which is what they are doing, but I would also put in a lot of money in getting the people that live there on board and voting if they could manage to put their only elected representatives in there locally, they are far more likely to make a difference than they will by changing the financial incentives here.

[End Clip]

Greg Dalton: That’s UCLA Finance and Economics Professor Ivo Welch. Lynn Doan, he’s saying look, it's not gonna hurt the bank, be political. Your thoughts on that and also the question about the divestment campaign.

Lynn Doan: I think I would agree there has been impact but it has been limited. So I'm sure the person who asked that question is probably already aware that there were actually 17 banks, different banks that were involved in the financing of the loan that helped pay for Dakota Access. And the divestment campaign did spur some of those banks to end up transferring those loans. Three, I believe ING, D&B and BNP. And so, there's that. But there's also the fact that there are still 14 other banks that have those loans that are helping finance and also the fact that those loans didn't just go away when they transferred them. They just sold them to another person that is then going to now hold that loan to Dakota Access. There've also been spurred initiatives at banks like Wells Fargo, so there was a proposition that a shareholder put forth there in which they asked the company to impose a policy in which indigenous peoples’ rights were taken into account when they're making their investment decisions. That shareholder vote got about 17% approval, and that sounds small but, you know, keep in mind that these shareholder propositions often don't garner very much approval at all. So that's actually pretty high for one of those. I think that if people are looking to be more environmentally conscious or drive change in investors’ attitudes to how their money affects the environment and the communities around them, there are a growing number of ways to do that. There are now indices that track environmentally conscious and like ESG-focused companies.

Greg Dalton: Environmental, social and governance.

Lynn Doan: Oh, sorry. Yes. And actually, Bloomberg helped sponsor a report recently that showed that asset managers had more than $18 trillion worth of assets that they made investments in with some kind of ESG metrics taken into account. On top of that, there was another survey that we reported on that showed that asset managers for the first time the majority of the world’s largest asset managers are now taking climate change into account in their investments. So there is movement afoot that is larger than the divestment campaign that is having some kind of impact and how investors are making those decisions on where their money is going.

Greg Dalton: Lynn Doan is a reporter for Bloomberg. Pennie Opal Plant.

Pennie Opal Plant: Yeah, I would like to add something to that. There's another part of this conversation that very rarely gets spoken about, and that is that because of the divestment movement millions of people across this country has started looking at their money and where their money is. At some point I pray and hope that there will be a tipping point where regular citizens like us will say, “you know what, every penny that I have I'm going to ensure that it goes towards something healthy and positive, and I am not going to put it in any of these big banks that are harming what we need to simply exist. And I’m going to start working on how do we make a community bank where I live.” And those conversations are happening across the country and that's very, very exciting and that could, you know, completely shift on the ground. I'm not talking about Wall Street. I'm not talking about these huge finance corporations. I'm talking about where people live, what they do with their money. And, you know, a bazillion pennies is a lot of money. And the system won’t work without all of us giving our consent to it working.

Greg Dalton: L. Frank.

L. Frank Manriquez: Yeah. You know, all those Santa Monica's can add up and there's another thing is that we are visible. We are visible in the street. So if people in government are looking at us and we’re having to scream, we’re having to be very loud. And we don't want to be loud. We want people to do what we we've elected them to do. But since they are not, then we are going to become visible. And we natives we are invisible a lot and we know how to become visible. And so staying visible, you know, like we've been dealing with Wells Fargo they came to California and there was some Emancipation Proclamation stuff going on that got ignored over here and we were actually slaves. And Wells Fargo they paid out $1 million one year to capture all us little Indians. So we're really familiar with banks and what we had to do with banks. I don’t need to go to UCLA to know what to do with a bank.

Lynn Doan: I think the idea that there's a growing awareness, I mean, one testament to that is the fact that outside of the Bloomberg terminal, outside of the terminal that professional investors subscribe to, Bloomberg just last month established a website, just for a plug, climatechanged.com. And that website, which is open to a general audience, anybody who goes to climatechanged.com, is 100% dedicated to explaining the business, finance and markets impact of climate change. And so I think you know if there's some proof that there is a sort of growing awareness among all investors as opposed to just professional investors, there is the fact that there was enough interest that Bloomberg established that.

Greg Dalton: One more tool is there’s fossilfreefunds.org. You type in the ticker for any mutual fund and they will tell you how much fossil fuel is in that mutual fund that you may own. Let’s go to our last question. Welcome to Climate One.

Female Participant: Hi. My name is Nicole. When I heard a professor from my alma mater come in and sort of disparage activism, I had to come storming up here and of course the panel did a much better job of articulating how, you know, it doesn't change overnight but we’re already seeing these actions targeting the financial institutions, cause people to take notice and start to calculate this risk whether it’s the 25 million that's lost from the delays in Dakota Access Pipeline or the reputational risk. So instead I’m gonna ask what gives you hope.

Greg Dalton: Pennie Opal Plant.

Pennie Opal Plant: The children. The children give me hope. These young people like 35 and under that are brilliant and inspiring and wise and powerful and willing to put it all on the line to make sure that their great-great-grandchildren survive. And I know them. I know these young people and they are amazing. And they were born just in the nick of time. And they give me hope.

Greg Dalton: L. Frank Manriquez.

L. Frank Manriquez: For me it’s more obligation. My ancestors have been visiting me before I was born and all throughout when I was born and during the 60s when I was doing other things, and other people were partying and I was getting visitations from ancestors with plenty of obligations on the plate. So it's really about doing what I'm here on this planet for. And that is one step in front of the other, and it's for children, it's for animals, it’s for the air. I can't really question because it's not my place to question what it's for, the creators said to do this. So the whole part, I mean, I love millennials, I love them to death. It’s a whole new mindset. I just love it. But the hope is not so much hope as to keep continuing that foot one after the other.

Greg Dalton: Lynn Doan.

Lynn Doan: I think I would go back to the growing interest just in general in the impact that climate change and that these other issues have, and the fact that there is a readership for it on the reporting side. And as long as there is a readership for it and people are actively asking for that kind of information we as journalists are going to provide it.

Announcer: Greg Dalton has been talking with Lynn Doan, lead oil and gas reporter for Bloomberg News. L. Frank Manriquez, indigenous artist and activist who went to Standing Rock. And Pennie Opal Plant, co-founder of Idle No More SF Bay.

To hear all our Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast at our website: climateone.org, where you’ll also find photos, video clips and more.

Please join us next time for another conversation about America’s energy, economy, and environment.

[Applause]

Announcer: Climate One is the sustainability initiative at The Commonwealth Club of California. Greg Dalton is our Executive Producer and Host. Jane Ann Chien is the producer. Kelli Pennington Directs our Audience Engagement. Carlos Manuel is our Booker and Associate Producer. The audio engineer is William Blum and the editor is Devon Strolovitch. The Commonwealth Club CEO is Dr. Gloria Duffy.

Climate One is presented in association with KQED Public Radio.