Dismantling White Supremacy to Address the Climate Crisis

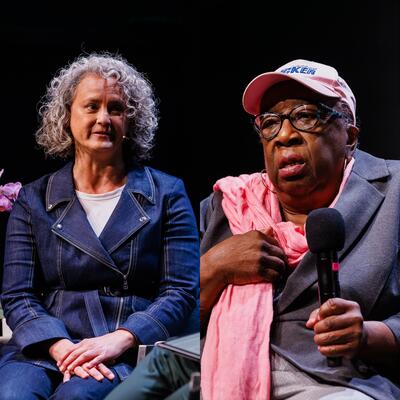

Guests

Leah Thomas

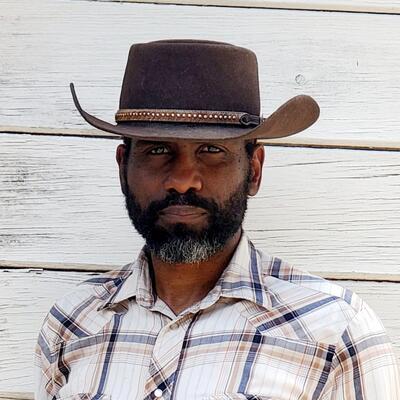

Hop Hopkins

Summary

We know that the climate crisis doesn’t affect everyone equally. A fundamental injustice of the climate crisis is that those who have contributed to it least are being impacted the most. This inequality will only be exacerbated as humanity continues to cause global temperatures to rise.

Hop Hopkins, director of organizational transformation at The Sierra Club, doesn’t mince words when discussing the roots of white supremacy in the climate crisis:

“Climate change is caused by white supremacy… We’re in this global mess because we have declared parts of our planet to be disposable, right. And for such a long time that disposability and extraction was happening in places that weren’t majority white that folks could escape from. And so, the cumulative impact of that disregard for those environments and those peoples meant that now the whole planet is a wasteland so no one is going to escape the detrimental impacts of climate change. And so, as we head deep into the climate crisis what we need to understand is that there are those among us who might promote fear and anger and who will seek to divide people based on their identities. And a lot of suffering is gonna take place in the US, as well as elsewhere. And when people suffer, they often look to find someone to blame for that suffering. Usually those are marginalized people based on their race or their immigration status.”

In her new book, The Intersectional Environmentalist, Leah Thomas presents a new model for working together to solve interconnected crises, tracing the origins of the ecofeminism, environmental justice and other movements to guide a new kind of work that centers the voices and experiences of Black, Indigenous and people of color.

This is how Thomas defines intersectional environmentalism:

“I think intersectional environmentalism is more of a lens to think about environmental issues and the goal is to be environmental justice, land back, those sorts of things, etc. So, I would say thinking about environmentalism through a lens of diversity and inclusion will naturally kind of pivot you to understanding and learning about movements like land back. Learning about the history of the environmental justice movement. Because when you’re thinking about the protection of both people and planet and the most vulnerable people then it’ll naturally kind of guide you to those sorts of other movements.”

When thinking about how she came to intersectional work, Thomas reminisces, “I bought the environmentalist dream through and through. I was a park ranger in the middle of Kansas and like, you know, I was a conservation girl. So, I was frustrated at times because I made a lot of great friends along the way and it made me question those friendships because I would go to protest with them and the reason I mentioned salmon so much is actually because I was one of the last environmental protest I went to was a protest to save salmon. And I went with like hundreds of coworkers and local activists that I knew and then when it came to racial justice movements they weren’t there. Many of them were not there. And when I would talk to them about it they would say, you know, this is more of a racial issue; I’m an environmentalist. And for years I kept hearing some sort of iteration of that, you know, I'm an environmentalist, the people thing, the social thing, the human rights thing, that's not really my thing. So, I think that was the frustration of just it has to be your thing how can you care about the earth and not the people on the earth? That sounds silly. So, I had a bit of a moment and never stopped talking.”

Related Links:

https://www.intersectionalenvironmentalist.com

https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/2021-4-fall/top/invitation-save-planet-ending-white-supremacy

https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/racism-killing-planet

Full Transcript

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious. We know that the climate crisis doesn’t affect everyone equally. In recent years, largely white environmental organizations have been reckoning with the communities whose needs have been ignored.

Leah Thomas: I would argue that most of the movements that we’ve had have been very specialized for a very long time in the United States and not thinking intersectionally I think is why we keep having to have these racial awakenings and environmental movements over and over again.

Ariana Brocious: What is the best way to address these injustices?

Hop Hopkins: Our work should aim to uncover those connections at the intersections of race, gender, ability, class and geography. And the challenge with representation is in these institutions like this. It’s not a problem that there is majority white it’s a problem that the way in which they approach the policy solutions don’t incorporate black, indigenous and those communities.

Ariana Brocious: Dismantling White Supremacy to Address the Climate Crisis Up next on Climate One.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious, in for Greg Dalton. A fundamental injustice of the climate crisis is that those who have contributed to it least are already bearing the greatest impacts. And as global temperatures rise, that’s only going to get worse. Real progress on these issues cannot be made if hard hit communities are left behind and ignored. In her book, The Intersectional Environmentalist, Leah Thomas presents a new model for working together to solve interconnected crises, tracing the origins of ecofeminism, environmental justice and other movements. Her approach centers the voices and experiences of Black, Indigenous and people of color. She walked Climate One host Greg Dalton through the tenets of intersectionality.

Leah Thomas: Basically, humans are really dynamic people. So, we have different aspects of us whether that's a religion and spirituality, race, gender or age where we’re born on and on and on. And all of those things contribute to who we are, how we identify ourselves and how other people around us identify us. So, intersectionality is looking at all those different components that might contribute to a person or a philosophy or a system.

Greg Dalton: Sure, yeah. I think we have sometimes a single action bias. We think that A causes B and it’s linear and direct causality. And what I hear you saying is, yeah, there’s many factors and systems of oppression, especially for marginalized groups. help us understand why movements like second wave feminism which sought to improve the collective rights and status of all women could still be exclusionary.

Leah Thomas: So, second wave feminism and I'm speaking specifically in the United States in my opinion was a really incredible movement and initiative. However, a lot of second wave feminist groups kind of focused more so specifically on I guess white feminism. Not intentionally but a lot of the activists that were a part of that movement were white. So, when they were thinking about advocating for the rights of women and it was kind of through their perspective and race maybe wasn't something that was super pertinent to them and what they consider to be their oppression. So, some of the issues that we saw with the second wave feminist movement is that there wasn’t a lot of consideration for different experiences of women whether that was talking about their race, talking about their sexuality talking about their spirituality, etc.

Greg Dalton: Right. And so, I wanna bring in one more which is since its founding through today, the environmental movement has largely been composed of white privileged people in the Global North, we would say coastal elites in North America and Europe. What are some of the resulting harms of that and how is that compared to the feminism sort of white orientation you just mentioned?

Leah Thomas: So, the Earth Day movement in the United States largely happened in kind of the late 60s and the 70s. So, it was right after the civil rights movement and it was mostly like you said a lot of middle- and upper-class white people who are really passionate about the environment and kind of they brought their friends along with them and sometimes you know your friends might look a lot like you. So, whether or not it was intentional or not, they were advocating for kind of themselves because they did see environmental issues in their communities whether that was a lot of highways or air-pollution etc. So, they were pushing for a greener society but they’re also specifically talking about their neighborhoods. So, even though the environmental protection agency was created, Earth Day was created, all of these environmental laws and regulations to them may have thought, hey, you know, things are getting better in the 70s and 80s. However, because the movement wasn't intersectional, didn’t really include a lot of low income and people of color then we just see toxic waste sites getting kind of diverted to these vulnerable communities and staying away from wealthier and white neighborhoods. So, the problem didn't disappear, it just disappeared for them.

Greg Dalton: And if you talk about this in terms of people like I think of you say feminists I think of, you know, Gloria Steinem, if you say environmentalist I think of John Muir or some other white guy in the woods which shows my bias. And those are the icons of those movements. Would it make sense to say that those movements weren't inclusive of other people and how is that different than intersectional because inclusive like I can understand it a little better. Intersectional sounds like a kind of fancy academic word.

Leah Thomas: It is kind of a fancy academic work but I’m trying to make it fun because it’s also really fun to say. So, yeah, we can say inclusive but I think intersectional is even more comprehensive. Because to them the Earth Day organizers probably thought this is inclusive. There are people from you know different churches. There are hippies there’s spiritual people. Maybe people are mostly middle-class but I’m sure there’s a couple people who are also low income. There was one Chicano organizer so then maybe they thought this is the most inclusive thing. There are women there is children. It's great. So, perspective is everything. But if that's what they knew they maybe didn't even know that it wasn't inclusive by saying my standards. And I think intersectionality is important because like we’re talking about inclusion can mean very different things for different people. And with intersectionality you can make sure you're not missing anyone because for something to be truly inclusive you should also look at different things that I sometimes don't even think about like race and income, ability and disability things like gender and on and on and on.

Greg Dalton: When I hear intersectional, I think of people I've interviewed who’ve educated me that, know, fossil energy put in clean energy job done. That's not that keeps the existing structures in place and that’s where some people are right. That's where kind of the traditional white environmental movement was. And I've learned from people like oh no capitalism patriarchy they kind of come from these extractive capitalism and patriarchy are intertwined you cannot solve one without the other inclusively. And that's where it gets complicated because some people would say, whoa that’s more than I’ve signed up for. That sounds too ambitious. The climate will fry while we’re trying to solve all those deep things.

Leah Thomas: I would say that it’s easier to think of solutions through an intersectional lens. Not always at first but it saves you a lot of time and momentum in the long run. So, for example if you are thinking about say there is endangered salmon in Montana and you know the waterway is polluted. And if you are only thinking through the lens of let's protect the ecosystem and the salmon then okay maybe you would address the salmon issue if you had, you know a couple solutions. But then what you're missing is okay are there indigenous communities that depend on this waterway for their livelihoods. What is the timeline for fixing it if you're not considering those people then maybe you could say this project restoration could take two years. But if you're considering the health and safety of indigenous people, then you might address it faster and make sure that they're okay. And then to take it one step further okay, are there fishermen or farmers that also depend on this waterway. How is this negatively impacting them? What about their jobs and their livelihoods? By considering the people as well as the salmon and the water and the environment. You can make sure you don't have to years later, then put all the spending and ideating of how can we make sure the farmers and fishermen are okay. How can we solve the water issue that indigenous communities are facing? So, you can have more comprehensive solutions. They’ll never be perfect but you can prevent a lot of kind of cleanup years later.

Greg Dalton: Sure. Think of holistically and systemically in ecosystems. There are unfortunately we know innumerable past and current examples of environmental injustice. The placing burden of pollution, energy production contamination disproportionately on communities of color. And the environmental justice movement began in the 1990s with some white people, mainly people of color and people of faith. As the environmental justice movement has grown and evolved, what have been some of the successes in the last 30 years or so?

Leah Thomas: I would say one success, I don’t know if I would call this a success but it’s just the awareness of it. So, for example, when you’re talking about the placement of toxic waste facilities and things like that someone might be able to say, oh my god it’s so unintentional. But there's been so many studies that look at redlining and things like that when there was housing discrimination which placed black communities in specific areas. And seeing that okay the toxic waste sites are in formerly redline neighborhoods which are still primarily black and brown neighborhoods. So, I think one of the successes of the environmental justice movement was maybe not having the data to prove it in the 80s and 90s but now we have the data because they’ve been researching it for over 30 years. And we can say okay, even things like tree cover is closely tied to income and whether or not a city has the presence of trees. And then you can look at various factors like race and income and how those things play with each other and where certain environmental hazards are placed. So, I would say that’s one of the biggest successes having the data to back it up.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, and anecdotally, Dr. Robert Bullard, the father of Environmental Justice, one of his earliest cases was a middle-income black neighborhood in Texas where there was going to be siting of an industrial facility. So, he says that debunks the story oh it’s low income it’s property value it’s not race because this was not a low property value area. You write that following the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 you didn't want to be an “environmentalist” if that meant that you had to choose between racial progress and environmental progress. Where did that realization take you?

Leah Thomas: Yeah it was definitely a couple years in the making. I had worked as a National Park Service Ranger intern at different kind of government agencies and also in corporate sustainability at places like Patagonia. And in each of these spaces very well-intentioned people but I continuously heard things that were kind of like well, you know, racism isn’t the most pressing issue. The most pressing issue is the climate crisis. And I think over time I just had a big wake-up call. Like I can care about these things at the same time. And I do it naturally, that's just the way that I'm wired. I care about my people and other people and other oppressed people and my care for people is also why I care for the planet and I know that there's so many other people who feel similarly. It's impossible to separate those things, you know, it would be insane if someone said, oh you have to separate your care from animals from your care for the environment because they are so closely linked and tied. But to answer your question more specifically, where did this realization take me. I started speaking about it a bit more and some of my frustrations and I found very clearly that I'm not alone. There are hundreds of thousands if not millions of people who feel similarly and want to advocate for people and planet and animals at the same time. And that led me to found my organization Intersectional Environmentalist and also write a book.

Greg Dalton: You spent years dreaming about becoming an environmentalist and then felt abandoned by the environmental community during acts of unjustifiable violence against people of color. I’d like to hear more about that and conversations you had with white environmentalists about their ability to turn off those protests for racial justice.

Leah Thomas: Yeah, I mean I bought the environmentalist dream through and through. I mean I was a park ranger in the middle of Kansas and like, you know, I was conservation girl. So, I was frustrated at times because I made a lot of great friends along the way and it made me question those friendships because I would go to protest with them and the reason I mentioned salmon so much is actually because was one of the last environmental protest I went to was a protest to save salmon. And I went with like hundreds of coworkers and local activists that I knew and then when it came to racial justice movements they weren’t there. Many of them were not there. And when I would talk to them about it they would say, you know, this is more of a racial issue. I'm an environmentalist. And for years I kept hearing some sort of iteration of that, you know, I'm an environmentalist, the people thing, the social thing the human rights thing that's not really my thing. So, I think that was the frustration of just it has to be your thing how can you care about the earth and not the people on the earth. That sounds silly. So, I had a bit of a moment and never stop talking.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, what’s this saying about, you know, three white people talking about race. There’s something about like that's yeah, that we have the privilege of not talking about it because white is sort of the de facto group. This may be a bit of an aside but I’m curious, you know, working for the National Park Service, were you aware of the legacy of the Park Service? I'm a big fan of documentary films. Peter Coyote, America's Greatest Idea and like wow and then I was like, you know, kind of got whitewashed in terms of what the park service just did in terms of, you know, to indigenous people. So, as a woman of color kind of buying into that vision and here it was maybe built as strong of the Park Service were you aware of that legacy?

Leah Thomas: Oh, my goodness, no, and that shattered before my eyes. And the thing is I actually was working at an historic site in Kansas, so it had a lot of black history because I was working at it’s called Nicodemus. So, it was the first place west of the Mississippi after slavery, where newly freed Black Americans went to to start their own city. So, they kind of built dugouts and homes from the ground up, their own post office, their own school so when I was a national park ranger. It was so closely tied to my identity that I felt pride in that space and it being preserved by the National Park Service system. However, the more I started to lean into the story I started to learn a little bit more about indigenous identity and then I started learning about the displacement, often violent displacement of people. And that was really earth shattering for me and I think it was an important moment to realize that like with intersectionality duality can exist. I can love and adore the parks but also deeply understand the history behind it, the painful history behind it. Acknowledge that history, not be defensive and see if there's anything that I can do to improve a better future for conservation.

Ariana Brocious: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about intersectionality in the environmental movement. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods. Coming up, how focusing on the future can ignore the needs of the present:

Leah Thomas: They’re saying I want my future for my grandkids to be fine, but my present is okay. And to me there are people without clean air and clean water, and that is not complicated and we need solutions to address who is being impacted by that right now.

Ariana Brocious: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious, and we’re talking about an intersectional approach to environmentalism with Leah Thomas. Critical Race Theory has become a hot button issue in American politics, even though many people don’t fully understand what it means. Let’s return to the conversation between Climate One host Greg Dalton and Leah Thomas, author of The Intersectional Environmentalist, to learn how critical race theory relates to environmental justice.

Leah Thomas: Critical race theory basically says that race is a social construct that societies assign meaning to. And what that basically means like obviously, you know, there are white people there are black people there’s different people. People have different races but assigning a meaning or value to that is bad. Just saying that white people are better or superior. That is not good, it's incorrect. It is a social construction. But when that exists it positions certain races in particular in the United States as more powerful and better and kind of when you look at the power structures in the United States, whether it's the courts like who CEOs are etc. there's a power imbalance along racial lines. So, critical race theory argues that if one group is assigned more power and as a society, there will be systemic oppression with that group and we have seen that in the United States. So, what critical race theory is not is saying that white people are bad, but it is acknowledging that in the United States there is an imbalance of who is in power along racial lines.

Greg Dalton: Right. A lot of people associate American history built on systemic oppression. Therefore, I'm bad or the story that I've been taught and the story I told myself is flawed or wrong and that's a hard thing for people to accept. How do you position your work in relation to other movements like the land back work around reclaiming land language and more stolen from indigenous people?

Leah Thomas: I would say that these things coexist, and I think intersectional environmentalism is more of a lens to think about environmental issues and the goal is to be environmental justice, land back those sorts of things, etc. So, I would say thinking about environmentalism through a lens of diversity and inclusion will naturally kind of pivot you to understanding and learning about movements like land back. Learning about the history of the environmental justice movement. Because when you’re thinking about the protection of both people and planet and the most vulnerable people then it’ll naturally kind of guide you to those sorts of other movements.

Greg Dalton: Right. And what does restorative environmental justice look like to you and what would be an example of that?

Leah Thomas: I think one example I know reparations can sometimes be a trigger word for some people but in order to have restorative justice then I think there does need to be an element of climate reparations. So, one example of that is say there is a small island nation that does not emit a lot of greenhouse gasses does not, you know, use a lot of the oil is a very sustainable country. However, because of the climate crisis they’re no longer going to have a country to inhabit because of countries like the United States. So, if they have to flee their country because of sea level rise and climate change, then maybe there should be some sort of funding from the United States and other countries that have contributed to the climate crisis so they can not have a refugee crisis and have a place to live and preserve their culture. So, I would say that's an example of restorative environmental justice, making sure people who have felt the impacts have a brighter future.

Greg Dalton: In an initiative called Justice40, President Biden has pledged to deliver to disadvantaged communities at least 40% of the overall benefits from federal investments in climate and clean energy. How would you rate Justice40 so far?

Leah Thomas: The Biden administration has decided not to consider race to be one of the things that they’re acknowledging as the reason why different communities are disadvantaged by environmental injustice. --

Greg Dalton: I think the reason for that is that the civil rights laws sort of like unintended consequence, right? The civil rights laws are for good reason were argued for and put in place to take race out. But now if you want to put race into direct resources ironically the civil rights laws could make that illegal.

Leah Thomas: It’s so true and it’s so complicated. And I think that's why we’re running into intersectional environmentalism and I think they're doing what they can in an imperfect system. So, if that’s strategic to get funding and resources to the communities that need it most then I’m all for it. I was really excited even when this new administration came in. Their communications department reached out to my little tiny organization Intersectional Environmentalist and they said, hey, we know that you all are communicating with people who need to hear this information that may be don’t listen to the White House. So, is there a way that we can collaborate and share more information about environmental injustices together. And I thought that was so cool, little old me in Santa Barbara. So, and I love that they have one of the first environmental justice councils which is intergenerational. I think maybe there's some concerns because people keep leaving and coming in and out, but nothing is ever perfect the first time.

Greg Dalton: So, as I hear you talking about intersectional it certainly connects with my kind of holistic thinking and spiritual orientation about it's all connected. And yet, I also hear that we have climate emergency and urgency and it sometimes narrowing things and focusing and breaking things into pieces is the way that our legislative and political process can work. It's how much we can handle, you know, specialization. So, I'm asking you to be integrated and intersectional in this way in looking at all these interconnected things, does that lead to virtuous but slower progress and action. And do you see the utility of like okay yes, we got to prioritize we can't change all these things at once patriarchy and capitalism. And that’s where kind of like, you know, they’re like we’ll get to your people of color issue later we got to save the climate first. So, your thoughts on the speed and practicality of this approach.

Leah Thomas: I would say where did specialized thinking get us in 2022? Because I would argue that most of the movements that we’ve had have been very specialized for a very long time in the United States and not thinking intersectionally I think is why we keep having to have these racial awakenings and environmental movements over and over again. Because to me I think specialization is important and people should use their specific skills in ways that they’re only good at for the movements that they care about. I think my argument is more so that people should acknowledge the intersections and be aware of them. Because when they’re aware of them they can create better solutions even with the things that they're specializing in. So, if someone is incredible when it comes to economic reform, I think they should also consider how the climate crisis might factor into all of that. I don’t see the limitation of thinking that way and I don't have examples yet on a really broad scale in the United States people saying, okay, let’s do away with specialization.

Greg Dalton: Well, I mean the Green New Deal was a big sort of like jobs and security and everything. And they got a lot of pushback even from some very liberal people. Barney Frank saying, hey, America can only handle so much change at once. And yes, these things might be connected with the legislative process if you’re talking about legislation, I think it's a little different than talking about social movements. And you point out even the civil rights movement was, you know, men, right. It was Dr. King and John Lewis and mostly men, yeah, Rosa Parks, but it was mostly men, right?

Leah Thomas: Yeah. So, what I hear from a lot of white kind of well-to-do environmentalists is this sentiment of it’s too complicated I just want to focus on you know, reducing greenhouse gas emissions. But they don't realize the privilege that’s kind of wrapped into that because they’re saying I want my future for my grandkids to be fine, but my present is okay. And to me there are people without clean air and clean water, and that is not complicated, and we need solutions to address who is being impacted by that right now. So, I would say thinking about who’s being impacted the most in creating solutions and legislation that will address that as soon as possible is not virtuous thinking. But I get where people are coming from, but I think what I hear when people say that is that I'm okay in the present. My livelihood is not being threatened right now so I don't wanna think about these other things that you’re trying to make me think about little black girl. So, I don’t know about that.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I recognize that. I put myself in that category like the system mostly works. But I get it, right, that if the system works for you now you want to preserve it and just kind of change the energy source from one type to another and keep a lot of the rest of it in place. I’d like to borrow a question from your book. How can allies use their privilege to advocate for people and the planet?

Leah Thomas: I would say allies and in this particular case it might be people who I guess more specifically, if you’re not from a group of people that right now being impacted by environmental injustices. And that’s even me in certain situations. I live in Santa Barbara right now. It's beautiful. Then I can use my privilege and my comfort and lack of urgency because my needs are met to advocate for people whose needs aren’t being met right now and I can start having conversations. I definitely would say stay away from preaching to anyone but just having conversations with people in your life who might not know too much about this. Just like hey did you know down the street there's like 20 landfills? That’s ridiculous and someone might say, well, I never thought about that or I never thought about the fact that there is like no grocery stores in this neighborhood and there’s all fast food. And that's you know pretty messed up and whoa, you know, there’s so many conversation starters I think people can have to kind of spread the word of environmental justice as they see fit.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I like the part about no preaching. And I would add no persuasion because that really works. And I was really struck by Sabs Katz’s quote in ``The first thing for allies is just taking time to really genuinely listen and not to share fragility, or defend yourself for the privileges you hold.” So, that was interesting because I think I sometimes do that. Like I like, oh, she’s talking about me white privilege like I got like justify it. And I wonder, if you also feel a little bit defensive for your privileges even as a woman of color in Santa Barbara?

Leah Thomas: Absolutely. I think though, this is yeah, it’s such an important question like there are things that I don’t think about. I presently I don't think about disability and ability because I’m an abled body person presently. So, I remember there are a lot of conversations this is the biggest wake up call for me. I was talking about banning plastic straws. I was just on a tirade in college. And there is someone who let me know kindly, Leah, I need plastic straws to survive like it's the only way that I can consume the food that I can eat is with a bendable straw. So, if you want to advocate for inexpensive biodegradable bendy straws becoming the mainstream but I can't use your metal and pasta straws. And then I realized like that’s something that blew my mind that I wasn't thinking about oh okay my solution is just get rid of this thing, while well-intentioned, could be bad or what if everyone started shaming people without knowing that there are people who depend on these for survival or maybe it's all they can afford. So, that was a huge wake-up call for me to start thinking a little bit more, especially if I’ve been proposing really dramatic or absolutist solutions. And I think that's what drove me towards intersectionality because I was that really annoying environmental tyrant as many college students are and then realizing there’s flexibility and there's nuance to everything every problem and every solution should have nuance and flexibility.

Greg Dalton: Leah Thomas is Founder of Intersectional Environmentalist and author of The Intersectional Environmentalist: How to Dismantle Systems of Oppression to Protect People and Planet. Leah, thanks so much for coming on Climate One and talking about this. It’s really appreciated.

Leah Thomas: Thank you. This is great.

Ariana Brocious: You're listening to a conversation about intersectional environmentalism. This is Climate One. Coming up, how can large, historically white-led organizations change their approach to environmental and climate justice?

Hop Hopkins: Coming to terms internally and externally with the history of the environmental movement and trying to ensure that moving forward we really employ intersectional analysis about how we view the environment.

Ariana Brocious: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious. The nation’s largest, most prominent environmental organizations have typically been run by white men. Because of this, the needs of marginalized communities have often not been put at the forefront of the groups’ efforts. As director of organizational transformation at The Sierra Club, Hop Hopkins is one of the people working to change that. I asked what led him to that organization after years of working in the racial justice and environmental justice movements.

Hop Hopkins: For me personally it was a recognition that climate was a major issue as well as environmental injustices that I was seeing and experiencing as an environmental justice organizer. And recognizing that the Sierra Club was a huge organization; it had lots of power and clout in the policy space. I felt like it was an opportunity for me to get engaged with the organization and I'd gotten wind that the organization was really beginning to look at its work and trying to be more holistic in its approach to how it addresses environmental degradation and climate change. So, I thought it was an opportunity to get engaged and get involved to help the organization move to a place of being more holistic in its approach to how it was addressing those issues.

Ariana Brocious: So right now, the work that you do what is it look like? Can you describe kind of the work that organizational transformation consists of?

Hop Hopkins: Sure. So, my role as director of organization transformation is really about trying to help the organization develop intersectional analysis about how it does its environmental work, right? We wanna try to be more effective partners to social movements that we share goals and objectives and values with. It’s also trying to help clarify the organization’s role as part of a larger prodemocracy, profeminist multiracial intergenerational cross class climate movement and developing our practices and policies towards becoming an anti-racist organization. And what that means more specifically is coming to terms internally and externally with the history of the environmental movement and trying to ensure that moving forward we really employ intersectional analysis about how we view the environment, right, that we develop a holistic analysis that both incorporates ecosystems and human communities impacted first and worst by environmental degradation and climate change. That we center those communities and that we’re making efforts to educate both our base and our funders about the need to support that work.

Ariana Brocious: So, I think there's been a growing awareness really of some of the racist roots of the environmental movement and The connection between this sort of white nationalist white supremacy and environmentalism overlap. Could you just explain that a bit more for people who may be aren’t familiar with that history and what it looks like right now.

Hop Hopkins: Well, some of the founding members of the conservation environmental movement were also some of the founding members and leading voices in the eugenics movement. And as we know the eugenics movement was a very pernicious ideology that hierarchy a racialized hierarchy where white folks were at the top and anyone else below that in how dark you were along the color spectrum the less human you were almost. And so, that idea has permeated through the environmental movement and led to such things as blaming immigrants for a certain level of environmental degradation, right. So, we need to understand that as a part of our origins of foundations of the environmental movement come out of this, And so, not understanding that foundation makes it difficult for environmentalist to understand these dog whistles when they are spoken about and it makes it very difficult for them to separate what might be an eco-fascist environmental message and what might be a holistic intersectional environmental message. And we need to be able to continue to educate our base about some of these ideas and some of these groups are pushing these things. So, that when we’re out in the battle of the ideas for the narrative over a particular issue, our base is able to identify these specific messages that are coming from very racist places.

Ariana Brocious: Why is it important for majority white organizations like the Sierra Club to do this work of self-examination facing that legacy that the harm that may have resulted from years decades of work stemming from these roots?

Hop Hopkins: The Sierra Club has a valuable role to play as part of a multiracial intergenerational cross class anti-racism like I mentioned before. And primarily that role is to undermine white support for white supremacy. Black folks along with black and indigenous and people of color communities have been calling for a long time from the majority of white organizations like the Sierra Club to step up to this work for decades. And the Sierra Club has an open invitation from those communities to support solutions that marry the fight to end white supremacy and the fight for livable planet are those two things that are inextricably linked. Like the indigenous environmental networks call key fossil fuels in the ground or the more for black lives call for reparations to be included in policy approaches like the Green New Deal.

Ariana Brocious: As you do this work, do you find that there is a somewhat of a Catch-22, where people of color are less interested in joining or being part of an organization where they don't see a lot of other people of color, either in leadership or even in the membership.

Hop Hopkins: Yeah, I think that that is true. And personally, and professionally as I that bring it to the Sierra Club. I see anti-indigeneity, anti-blackness and anti-racism is central elements in all aspects of social justice working in the United States. our work should aim to uncover those connections at the intersections of race, gender, ability, class and geography. And the challenge with representation is in these institutions like this. It’s not a problem that there is majority white it’s a problem that the way in which they approach the policy solutions don’t incorporate black, indigenous and those communities. So, when folks come in and, one, don’t see themselves represented that’s one thing. But two, when they don’t see their community issues represented that's another thing. And those two things combined together make it a very unwelcoming environment.

Ariana Brocious: In a 2020 article on Sierra magazine you wrote, “You can’t have climate change without sacrifice zones, and you can’t have sacrifice zones without disposable people, and you can’t have disposable people without racism." So, we need to change that fundamental premise in addressing climate change in transitioning to a carbon free economy still requires power plants mining for minerals. These types of energy generation. So, how do you think we should share the burden of powering that future?

Hop Hopkins: Well, I think for the way that that burden’s been shared it’s been primarily in those sacrifice zones and those disposable people, right. And so, I think moving forward when we’re transitioning from both from a fossil fuel-based system to one that's more are regenerative in nature. We actually have to think about dividing the burdens of where that extraction happens, where that manufacturing happens, where that transport happens. As a rule I think that companies look for poor working-class communities in order to cite their extractive facilities. Because those communities are viewed as being less powerful, have less access to power ultimately has less resilience to fight and resist that project from moving forward. So, in essence, I'm saying we have to look at redistributing the way the burden has been inequitably placed and moving forward that the negatives are shared more equitably and also the benefits are shared more equitably.

Ariana Brocious: In that same article, you also write white privilege offers no escape from climate chaos. And I wanted to push back on that a little because isn't it kind of the case that wealth and privilege does insulate some people more than others with climate catastrophes, extreme weather things like that. And isn't that part of the problem of the structures that we’ve built?

Hop Hopkins: Well, what I meant when I said that is that we actually, you know, climate change is caused by white supremacy. And that was me in that article trying to highlight that, that we’re in this global mess because we have declared parts of our planet to be disposable, right. And for such a long time that disposability and extraction was happening in places that weren’t majority white that folks could escape from. And so, the cumulative impact of that disregard for those environments and those people meant that now the whole planet is a wasteland so no one is going to escape the detrimental impacts of climate change. And so, as we head deeper into the climate crisis what we need to understand is that there are those among us who might promote fear and anger and who will seek to divide people based on their identities. And a lot of suffering is gonna take place in the US, as well as elsewhere. And when people suffer, they often look to find someone to blame for that suffering. Usually those are marginalized people based on their race or their immigration status. And so, by expanding the way in which we view the impacts of climate change we can demonstrate that this is not something that just that community or that environment is experiencing. That the cumulative impact of that has us all in the crosshairs of climate change and climate chaos.

Ariana Brocious: During the racial justice protest in 2020 we heard a lot about white fragility, especially as a barrier to progress toward equality and justice. So, I’m curious how your work has been received within the Sierra Club by staff and by its membership.

Hop Hopkins: Well, it’s been an ongoing process long before I got on board in the Sierra Club. I mean there's been work of other black indigenous and people of color particularly African-American women inside the organization have been pushing the organization for a long time as well as white allies. And we try to come to the work from a position of compassion and empathy for the difficult and challenging work it is to take on an anti-racist approach to how we do our work because it’s very different than the work. It's very different than how the organization has taken on this work in the past. And with change any kind of change comes difficulties. And we’ve tried to manage that change as best we’ve could. And along the way we’ve made some strides and we’ve made some errors and will continue to experiment and continue to do that work.

Ariana Brocious: So, we often talk about policies or actions in pragmatic terms. You know that things can't be too radical, particularly when we’re talking about legislation for example, or they won't get anywhere. So, what compromises should and shouldn't be made when crafting intersectional climate policy?

Hop Hopkins: I’m not certain I’m understanding your question about compromise. I think that one of the things I think about is we coming to with the ground and assessment of action what we need in a moment paired with what's actually politically realistic. And then thinking about what are some of the false solutions that we are looking at and really trying to move. If we think about in terms of three circles really trying to move the circle of what we need and what's politically possible close in alignment with each other while moving away from false solutions. And what I mean by false solution I’m thinking about things that actually take a compartmentalized view versus an intersectional view to how we’re gonna address a systemic issue.

Ariana Brocious: Right. So, you know, there have been policies proposed that are viewed by some as just far way too out there way too moving too fast. If we try to accomplish that we’re not gonna get the political support we need and thus we won’t accomplish anything. So, are there specific policy examples you can cite that have suffered from this over compartmentalizing.

Hop Hopkins: Let me not point to one policy. I think we have to look at it more holistically and think about what has been the detrimental impact of taking a very narrow view to what environmentalism is and what environment is. When you separate people and communities from that analysis, it becomes very difficult to come up with a holistic approach. And what we’re saying now moving forward is that we have to also include ecosystems as well as people and communities as part of that assessment. So, when we’re coming up with policies, we have to make sure that we're addressing it in such a way that no one is left out or left behind in that equation. And even when we do that there may be critics about it going too far not going far enough. However, if you do it, not in isolation for example, if the Sierra Club just comes up with a policy on its own, but if it was in coalition with other communities black and brown, indigenous people of color working-class communities who are first and worst impacted by those things. And at the very outset of those policy discussions those communities and individuals and groups and movements who are involved we have a much better chance to coming up with a policy that's holistic and intersectional that ameliorates the challenges that we’re trying to face.

Ariana Brocious: So how does the latest IPCC report drive urgency around climate change and climate action?

Hop Hopkins: Well, what I’ll just say about urgency in general, I think, is that we need to be thinking about ameliorating again take in consideration those who are first and worst impacted. And one thing I want to say about urgency without not addressing your question is that urgency often leads to what we’ve been talking about is a less intersectional approach to how we’re gonna solve things. And I think that that's how we got into this situation in the first place. And yes, climate is urgent, but we also need to step back and take a look to make sure that all voices and all communities have a say in the policy approach, which we’re taking. I think that's critically important. I also think that looking at urgency as a motivator for change is also challenging. One of the things that I've been aware of and trying to deal with in our work is that the sense of urgency leads to a sense of hopelessness. And that sense of hopelessness leads to a very dystopian view of what the future might hold for folks. And that dystopic view oftentimes leads to scapegoating and really trying to come up with very narrow short-term solutions that actually have detrimental impacts in the short term for other communities who already are first and worst impacted by it. And that dystopian view also leads to one of the foundational elements of the conservation environmental movement that is not well known, which is some of the eco-fascist elements of it. And what those eco-fascist elements lead to is this kind of dystopic view and blame of black indigenous people of color communities for the environmental situations they’re in. It's actually erroneous racist view. And so, I'm very quick to step back away from urgency and as it relates to dystopic views. If we don't do this right now then we’re gonna fall off the edge of the planet because that view doesn't allow for a much more holistic approach that we’re gonna challenge something.

Ariana Brocious: Elsewhere in the show we hear from Leah Thomas of the Intersectional Environmentalist. And she said that after protesting an environmental cause some of her white environmentalist friends didn't join her at the black lives matter protests. And said, sort of, you know, that’s not my focus I’m focused over here that's not really my issue. I was curious if you've experienced something similar in the work you've done.

Hop Hopkins: Well, shout out to Leah, first of all, just say what’s up to her and appreciate the work that they're doing. No, I've never experienced that.

Ariana Brocious: That’s encouraging. Actually,

Hop Hopkins: I’m kidding. I'm joking. Yes, of course I think most people of color who are in this work have faced that. And I think those folks who would consider themselves allies in this work have faced that as well. And I think that's par for the course in terms of how the compartmentalization of environmental work has happened here before where it only looked at very narrowly and only looked at environmental very narrowly. They didn’t include communities and environments that were urban let's say, or rural that were populated by folks with less wealth or less access to power. The pushback has come from both the climate justice and environment justice communities that really, you know, challenged the environmental community to really take a more holistic approach to how it's viewing the environment and to take those issues on. And so, for sure when we began to look at issues I think white environmentalists who’ve come out of that orientation definitely were not able to see the intersections between how having the lack of clean air in a community is very much related to the lack of democracy and justice in the forms of police brutality and over policing and injustice. And it’s been through years of working both internally with our board members, staff, and volunteers also partnering externally with folks inside the climate justice community who have more holistic approach to how they do their work and folks in the racial justice community that the environmental community as a whole has been able to expand this approach in view of environmentalist to also include racial justice. And coming to the conclusion that climate justice is racial justice has taken a bit of time for large parts of the environmental movement. And I would just say all parts of environmental movement aren't there and it still continues to be a struggle. And again, that is a role of organizations like the Sierra Club who might be further along in their journey in their racial justice journey to then do work with other environmental community and organizations to help move them further into an intersectional approach to how they do their work.

Ariana Brocious: Earlier you used the phrase solidarity not charity, and I just find that really powerful. And I wanted to return to it and ask you if you would just sort of break that down again in helping people think through the gravity of what's at stake here and how we can be all working together to address climate disruption and racism and these other structures that we've built and created over generations.

Hop Hopkins: Yes, so I think it’s very important. I think as part of developing the intersectional analysis about environmental work is that previously I think that mainstream environmental groups came to this work from a place of charity, that they were going to do something for the benefit of other communities on behalf of other communities without really being in relationships with those communities. And without understanding that actually by addressing this issue was actually helping address issues that might be impacting them, although we are differently impacted, we are ultimately impacted if there is an injustice happening. And so, coming from a place of solidarity where you understand that my liberation is actually wrapped up in your liberation, that I'm actually not doing anything for you. I'm actually working in concert in relationship with you to solve an issue, gets us to a different place of being able see exactly and understanding what my skin in the game is. In this particular moment, it might look different than yours but ultimately me supporting you in your effort to ameliorate an issue that's negative impact in your community is a way in which of understanding that my humanity is also being negatively impacted if your humanity is being impacted. In terms of addressing white supremacy and eco-fascism understanding that that this isn't something that white folks are just be doing on behalf of people of color that it actually creates a truncated human experience for them because white supremacy and eco-fascism is requiring a certain level of compliance of them that truncates their own humanity, right. And so, at stake is not just mine because these negative things happening here, but it also is costing you as a person coming from the position of privilege because you actually have to cosign that oppression. And that cosigning often comes at censoring or truncating your own sense of self and humanity. And in a short term that seems like it might be a cost worth giving, but again looking at the impact cumulative impact of environmental injustice now the whole planet is at stake because we, for years and centuries relegated certain communities and population geographies to a certain level of environmental disposability and sacrifice that folks calculated was acceptable. But again, the cumulative impact of that is now the whole planet is at risk.

Ariana Brocious: Hop Hopkins is Director of Organizational Transformation for the Sierra Club. Hop, thank you so much for joining us today on Climate One.

Hop Hopkins: It was a pleasure. Appreciate you.

Ariana Brocious: On this Climate One... We’ve been talking about intersectional approaches to environmentalism. Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe to our podcast on Apple or wherever you get your pods. Talking about climate can be hard-- but it’s critical to address the climate emergency. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation. Brad Marshland is our senior producer; our producers and audio editors are Austin Colón and me, Ariana Brocious. Our team also includes Arnav Gupta, Steve Fox and Tyler Reed. Our theme music was composed by George Young (and arranged by Matt Willcox). Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. Our host and executive producer Greg Dalton will be back next week. Thanks for listening.