Oil and Opioids on Trial

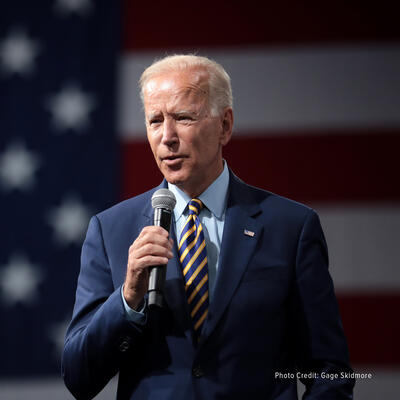

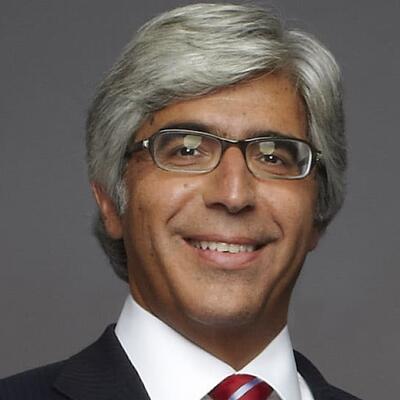

Guests

Ann Carlson

Ellen Gilmer

Theodore J. Boutrous Jr.

Scott Segal

Summary

What do Big Pharma, Big Tobacco and Big Oil have in common?

They’ve all been brought under fire, and into the courts, for knowingly causing public harm, and even death, with their products. You can include the gun industry in that list too. And, like the tobacco and pharmaceutical industries, evidence has shown that gas and oil companies have long known about the link between their product and increased greenhouse gases – and kept it to themselves.

“But they did more than that,” says UCLA environmental professor Ann Carlson. “It's not just that they knew about it, it's that then they actively campaigned to try to persuade the public that climate change was not connected to their product.

“So there's really deceptive practices involved here.”

Ted Boutrous, an attorney whose firm represents Chevron, disputes the characterization that the industry was covering anything up. Furthermore, he maintains that the fossil fuel companies aren’t entirely culpable in the climate crisis -- they’re only giving the public the oil and gas they want, and need, to fuel their daily lives.

“It's not just the production; it's the demand for it,” he says. “It's something we need for hot water. We need it for transportation, almost everything we do, the screens on our phones depend on fossil fuel products. And so we are really all in this together.”

Complicating the issue is the question of whether carbon emissions should be litigated or regulated. Scott Segal, of the lobbying firm Bracewell, sees it as a global issue, one that can’t be decided in state or federal courts, but is a matter for Congress to decide.

“One molecule of carbon dioxide emitted anywhere in the world is literally around the world within seven days,” Segal points out. “Which both shows the incompatibility particularly of state court actions, but also shows the necessity of having a policy-based solution rather than a judicially concocted solution.”

Should corporations be held liable for harmful outcomes like mass shootings, the opioid crisis, and climate change? How much responsibility falls on the product, and how much on the user?

Portions of this program were recorded at The Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco.

Related Links:

States Backing Climate Case Cite Litigation Over VW, Opioids (Bloomberg, Jan 3)

Could big opioid ruling bolster climate cases? (E&E News, August 2019)

Op-Ed: Why Big Oil fears being put on trial for climate change (LA Times, August 2019)

2019: The Year Climate Litigation Hit High Gear (Climate Liability News, December 2019)

Why Cities Suing Over Climate Change Want the Fight in State Court, Not Federal (Inside Climate News, July 2019)

Opioid judgement against major drugmaker holds hope for court action against U.S. fossil fuels (theenergymix.com)

Courts will be the climate change battleground (vnews.com)

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One, leading the conversation about energy, the economy, and the environment.

Evidence has shown that for decades, major oil corporations have known about the link between their product and climate change - and kept it quiet.

Ann Carlson: But they did more than that. It's not just that they knew about it, it's that then they actively campaigned to try to persuade the public that climate change was not connected to their product. So there's really deceptive practices involved here.

Greg Dalton: But Big Oil rejects the idea that their actions were designed to deceive the public.

Ted Boutrous: So I really just kind of want to debunk that point right out of the gate. We recognize there's an issue, we have to deal with it. Everybody bears responsibility, all of us bear responsibility for going forward as to how we address the issue.

Greg Dalton: Taking oil companies to court. Up next on Climate One.

---

Greg Dalton: What do Big Pharma, Big Tobacco and Big Oil have in common?

Climate One conversations feature oil companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats, the exciting and the scary aspects of the climate challenge. I’m Greg Dalton.

[music change]

Greg Dalton:Tobacco companies, opioid suppliers, gun manufacturers and the fossil fuel industry -- all have been brought under fire, and into the courts, for knowingly causing public harm, and even death, with their products. But there is an important difference, says environmental law professor Ann Carlson -- personal responsibility.

Ann Carlson: Climate change harms from oil companies, harm all of us. Whereas, one of the big distinctions that actually in some respects makes the opioid, and tobacco cases harder is that you have an individual who engaged in behavior that is contributing to the harm.

Greg Dalton:Ted Boutrous, who represents Chevron, recognizes the distinction too. But he maintains that his client and other fossil fuel companies aren’t entirely culpable - they’re only giving the public the oil and gas they want, and need, to fuel their daily lives.

Ted Boutrous: And so it's not just the production; it's the demand for it and it's something we need for hot water, we need it for transportation, almost everything we do depend on fossil fuel products. And so we are really all in this together.

Greg Dalton: On today’s program, we’ll look at recent litigation in so-called “nuisance cases.” Should corporations be held liable for harmful outcomes like mass shootings, the opioid crisis, and climate change? How much responsibility falls on the product, and how much on the user?

Joining me now are Ellen Gilmer, Senior Legal Reporter for Bloomberg News, who has been reporting on climate law for years. And Ann Carlson is co-Director of UCLA’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change & Environment. I asked her to tell us how tobacco, oil and opioid court cases are - and aren’t - connected.

PROGRAM PART 1

Ann Carlson: Tobacco, oil and opioid litigation are all related in a few ways. The first is just the basic legal case that plaintiffs made in the tobacco cases, and are making in both opioid and climate change nuisance litigation. That is under an old doctrine called public nuisance. Which is a pretty general concept that if somebody, a defendant, knowingly assists in the creation of a harm to a public right, then the plaintiff might be able to bring a case against that defendant. And there are lots of questions about what a public right is what it means to contribute to causing harm to a public right and so forth and we can talk more about those details. But that's the first similarity.

The second similarity is that in all three of these cases there is interesting and emerging information about what defendant companies knew. The tobacco companies, the opioid companies, pharmaceutical companies, and big oil about how their products caused harm, when they knew that information and what they did with that information that really perpetuated the harm and made it go on longer than it would have had the defendants acknowledged that their products were causing harm.

Greg Dalton: There seems to be a fundamental difference though, Ann Carlson, that tobacco, someone smokes a cigarette, and that smoke goes into their lung. Someone takes an opioid pill and the chemical goes into their body. But with oil it's very different, right, the harm goes into the atmosphere, and then it’s much more indirect.

Ann Carlson: It is a difference and I think one of the big questions is, is it a difference that makes a legal difference in court. But it's also worth noting that climate change harms from oil companies, harm all of us. Whereas, one of the big distinctions that actually in some respects makes the opioid, and tobacco cases harder is that you have an individual who engaged in behavior that is contributing to the harm. So in the case of a smoker, the smoker chose to smoke. In the case of an opioid user one, you know, argument that the defendants might make is that somebody takes opioids in a way that is harmful to them rather than helpful. Whereas, individual consumers are just using the products that oil companies produce to turn the lights on, or to operate their vehicles, and don't really have the same level of personal culpability at least from a legal perspective the defendants might try to argue about.

Greg Dalton: Ellen Gilmer, you’ve been following the oil and opioid connection in the courts. How are the companies in the cases looking at each other in terms of trying to learn, or not be like the other one?

Ellen Gilmer: Well, yeah it's really interesting there was actually a ruling in one of the opioid cases in Oklahoma in 2019, in which a judge sided with the state of Oklahoma against Johnson & Johnson which is a pharmaceutical company. And after that ruling happened people involved in the climate litigation were looking very closely at whether that meant anything for their own cases. You know, a single judge in a single court in Oklahoma interpreting Oklahoma law that's not binding in other courts, but it can be considered persuasive. So, you know, plaintiffs in the climate litigation were looking at it, to say hey this is helping our case, and you know, oil and gas attorneys were looking at it to see if there were any things that they should be nervous about in the climate litigation.

Greg Dalton: And why there’s a debate going on some people want these battles to happen in state court, some people want them to happen in federal court. Who favors what level of courts, Ellen?

Ellen Gilmer: So the plaintiffs, so we’re talking about these climate cases brought by local governments and the state of Rhode Island and cities. And they are all filing their cases in state court because that is where public nuisance claims generally arise. So they’re filing their case in state court they're talking about state law issues and harms to their locality. All the cases have been transferred up to federal court, which is something that a defendant can do if it's a question of federal law or for a variety of reasons. So they argue that hey, this is actually an issue of federal law because it's so broad in scope, it’s a global problem, this doesn't belong in state court it belongs at the federal level.

Greg Dalton: Ann Carlson, why do large corporations who are defending themselves prefer federal courts to state court?

Ann Carlson: Big companies that are defending themselves against these climate nuisance cases have a number of reasons they want to be in federal court. Probably the most important one is that there's a Supreme Court decision that was decided a number of years ago prior to the election of Donald Trump actually, prior to the election of Barack Obama, that said that the Federal Clean Air Act displaces or prevents plaintiffs from bringing public nuisance actions under what's called Federal Common Law. Which is something that federal courts kind of create and interpret themselves.

And so one of the things that oil companies are trying to do is to argue that these cases should also be displaced under federal law, even though they’re brought under state nuisance law. It’s a very convoluted and kind of complicated doctrinal question. And they think the federal courts are more likely to be sympathetic to those arguments. Then there’s a couple of other reasons. Another reason that they favor being in federal court is because there are some interesting constitutional questions, about federal courts deciding these cases that the defendants think are gonna be that judges in federal court are gonna be more sympathetic to them.

And a big one is a question of whether this is really a question that Congress ought to be considering, whether to regulate greenhouse gas emissions is essentially what they’re trying to say this is a federal really congressional question, as opposed to a court question. And courts getting involved in these questions are risking interfering with separation of powers under the Constitution. Frankly, I don't think those arguments are likely to prevail. I think the states that have brought these cases and the cities that have brought these cases have a better claim that they belong in state court, but that's not stopping defendants from trying to get them in the federal court. I think there's a third reason to and that is that the federal courts particularly since the election of Donald Trump are more conservative than many state courts. And so I think the hope on the part of oil companies is that they will be less sympathetic to plaintiff claims that the oil companies should be responsible for some of the harms the climate change is causing now and will continue to cause in the future.

Greg Dalton: Rhode Island is the fastest warming state in the lower 48. Alaska is the state that’s seen the most warming and Rhode Island is a close second already seeing 2°C of warming since industrial times. They’re suing Shell, Chevron, Exxon. Ellen, what is that case about and why are other states supporting it?

Ellen Gilmer: So, Rhode Island is suing those oil companies and saying that, you know, they are marketing, production and marketing and sale of fossil fuels is contributing to problems in Rhode Island. Sea level rise various other impacts of climate change that the state and state’s residents are experiencing on the ground. So they have raised a public nuisance claim among several other legal arguments against oil companies.

Greg Dalton: And is product liability, you know, the gun manufacturers have a liability shield from the 2005 Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act. There’s been a dent in that recently after Sandy Hook. Is product liability a factor in the oil litigation, Ellen?

Ellen Gilmer: In some of the cases they are blending in claims over product liability. So product liability is, you know, you made a product that ended up hurting people because of faulty design or you failed to warn the public about harms from a product. And so in some of the cases that cities and counties have filed they've said not only is this a public nuisance but it also violates these product liability provisions.

Greg Dalton: Ann Carlson, any parallels between guns, oil and these other products we’re talking about?

Ann Carlson: Well, the biggest difference is what you have already mentioned and that is that the gun manufacturers have pretty close to absolute immunity from lawsuits because of a congressional act. The oil companies have played around with trying to get Congress to immunize them from these lawsuits in the climate change context. So for example, one of the carbon taxes that has been proposed for a while included a liability protection provision it's actually been dropped from the proposal. So I guess that's the biggest difference. There are similarities again as Ellen suggested that when you have a product that you put into commerce and it causes harms that those harms can carry liability with them.

Probably the most straightforward way of thinking about it is that some of the lawsuits include failures to warn consumers about the harms of the product that was being sold. And in fact, in the case of the oil companies they’re actually in some respects more culpable than the gun manufacturers because they tried to hide the harms of their product from consumers by engaging in a campaign to dissuade the American public that climate change was occurring. Gun manufacturers I think for the most part don't deny that their products actually cause harm they’re in fact designed to cause harm if they’re use against other human beings. That’s something that the oil companies have not easily acknowledged and for many, many years denied.

Greg Dalton: Ann Carlson, one of the interesting things that came out of the tobacco cases was there were whistleblowers there were documents boxes of documents dropped on doorsteps portrayed in Hollywood films which often is a result of discovery that’s one of the key tools in these cases. What are we seeing in the oil and opioid cases in terms of documents coming forward because the tobacco stories and deals were played out before everyone had cell phones and email. Are we seeing the revelation of internal documents now as part of these proceedings?

Ann Carlson: We are starting to see in the oil company cases, documents, emerging about early scientific studies that the oil companies funded in the 1950s and 60s and into the 1970s that established really clearly the connection between the burning of fossil fuels and climate change and the kinds of harms that we're likely to see from climate change. In fact, there's some really remarkable documents that have come forward that show that the oil companies predicted with near certainty what the parts per million of carbon dioxide would be in 2020 looking a lot like what it looks like today. They also predicted that in the 20 teens I guess that’s the way to say it that there could be a super storm hurricane that hit the state of New York and that that kind of hurricane could increase public support for regulating greenhouse gases. Turns out, of course, that we had Hurricane Sandy that looks a lot like that prediction.

So we have documents showing that and then we have documents that show that the oil companies poured massive amounts of money millions of dollars into these campaigns to try to confuse the public about whether climate change was actually caused by the burning of fossil fuels. We’re only in a very preliminary stage however, most of those documents were revealed actually by journalists who found a trove of documents at the University of Texas library from Exxon showing a lot of this and we've also seen the uncovering of some documents from Shell. But the discovery process in the cases is only just beginning. So we are likely to see a couple of things through that process. One is requiring executives of oil companies to actually testify about what they knew and when they knew it.

So again we're likely to see discovery in these cases, presuming that they go forward and the discovery is something the oil companies really I think do not want made public.

Greg Dalton: How about Ann Carlson, one of the things, tools, is nondisclosure agreements is to prevent people from talking. What have companies learn from the tobacco case to either lockdown information or to prevent something like that happening to their industry?

Ann Carlson: I’m not sure that we've gotten far enough yet to know the answer to that question. But one really interesting development that could occur is if one of these cases succeeds. So there, as Ellen said, there about a dozen, 12 or 14 of these cases that have been filed around the country. If one of them succeeds and a municipality gets damages to either prepare for the climate change effects that are going to impact their jurisdictions or to pay for damage that has already occurred, then you're likely to see the floodgates open so to speak, no pun intended there. Where you’re gonna see municipalities around the country looking to see whether they should also be filing cases, that's really parallel to what happened in tobacco.

Ellen Gilmer: And a lot of cities and states are watching the cases that have already been filed really closely and thinking about filing their own. We already have a couple of municipalities in Hawaii that are working on filing cases as they've watched these initial ones go through their preliminary steps.

Greg Dalton: And Ellen Gilmer, the industry had a very interesting response to these counties filing public nuisance cases which is, hey you municipalities, counties, you wish you public municipal bonds to build infrastructure roads and airport and you don't fully disclose the climate risk in the bonds you're selling. Right back at you.

Ellen Gilmer: That's true, there's been a big fight over that. And, you know, there's been a lot of reporting on that a lot more to come. So that’s gonna be an issue that’s gonna come up in all of the court documents too.

Greg Dalton: Ann Carlson, the tobacco litigation started in the states and ended up with a $250 billion universal macro settlement. How do you think this might play out in oils it’s gonna be lots of states and then as you said start to hear the first jury verdicts or verdicts is there a grand bargain that is on the horizon that people think might happen like tobacco?

Ann Carlson: I think it's a little too early to say whether any kind of grand bargain could emerge. These preliminary legal scuffles about whether the cases belong in state or federal court are just the beginning of a lot of motions that the oil companies are gonna file trying to get rid of the cases so they never even get to a jury. And then there are really complicated questions about causation about relative contribution from one company versus another versus companies that aren't even in front of the courts in these cases. And what level of damage climate change is responsible for say with respect to wildfires which are naturally occurring but have gotten worse as a result of drought and higher temperatures.

So I think we’re a long way from knowing kind of whether one of these cases is gonna succeed. If they do succeed however, you know, I could imagine some sort of grand bargain that involves some effort by municipalities to get compensated for at least some of the harms for particularly the most provable climate change harms; sea level rise is the best one of those where there's really a linear relationship between rising sea levels and rising levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. But I think we're a long way from really try to figure out what that would look like and whether it will occur assuming that we get a successful jury verdict.

Greg Dalton: And there is shared culpability responsibility, right. We all use fossil fuels every day. But is it -- seems true to me that the oil companies knew their product was harmful before the public generally did. That they knew first before the public realized that their lifestyles were causing these problems, is that fair?

Ann Carlson: The oil companies have known since the 1960s even earlier that their product contributed to accumulating greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, which was gonna cause climate change there’s no question about that. But they did more than that. It's not just that they knew about it, it's that then they actively campaigned to try to persuade the public that climate change was not connected to their product. So there's really deceptive practices involved here.

The other thing to note is just that the vast majority of greenhouse gases have been contributed in the last 30 years and there's a relatively small number of defendants or oil companies that are responsible for a very, very large proportion of those greenhouse gases. So that makes this question of liability a stronger one for the plaintiffs and easier for a court to think about how you might actually portion damages if you get to that stage.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about climate change liability. We’ve been speaking with Ann Carlson of UCLA’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change & Environment, and Ellen Gilmer, Senior Legal Reporter for Bloomberg News.

Coming up, two attorneys who believe the oil and energy corporations they represent shouldn’t have to shoulder all the blame.

Ted Boutrous: It really is a situation where we’re all in this together. And from a legal perspective, it makes no sense to really say it's those who are producing something that really contributed to the modern society, it's the way civilization is developed. [:15]

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton and we’re talking about climate liability. Who should take responsibility for the climate disruption caused by fossil fuels? Harvard historian Naomi Oreskes and others have proven that oil companies spent millions of dollars over decades deceiving the public about the fact that burning fossil fuels disrupts the climate. Who should take responsibility now?

Joining me now are Ted Boutrous, an attorney in Los Angeles at Gibson, Dunn and Crutcher, who represents Chevron, and Scott Segal, partner at the Washington DC lobbying firm Bracewell, where he represents energy companies.

To start things off, here’s a clip from a 1991 documentary produced by Shell Oil. As you’ll hear, it offers a rather unexpected take on global warming.

PROGRAM PART 2

[Start Playback]

Male Speaker: Global warming is not yet certain, but many think that the wait for final proof would be irresponsible. Action now is seen as the only safe insurance. But what should that action be? If the threat of global warming is to be realistically addressed the future will need to be different.

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: That’s a Shell Oil film produced 30 years ago. Ted Boutrous, what's your response to what the oil companies knew 30 years ago, and what they were saying publicly in the subsequent 30 years?

Ted Boutrous: Well, it really is interesting because back in 1990, that was the beginning of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, which is really the leading group of scientists. And back then the IPCC as it's known and it's a UN organization was saying, look, that we see a change in climate. We think that human activities are contributing to that and we think there could be serious consequences but we’re not sure and there was uncertainty. And so science has gotten better and better and clearer and clearer on these issues. And the United States government back in 1965 President Johnson issued a proclamation saying that that there is this issue and that human activities are contributing. So there was a lot of knowledge, a lot of scholarship out there and the question is always been how to grapple with those issues and adjust to our energy needs our national security needs our economic needs while addressing climate change. So it sounded, I had not heard that clip before it sounded like that was the theme that they were sounding there and it carries through this day we’ve got an important global issue. I think that the energy companies the oil and gas companies can be big participants in helping solve the problem

Greg Dalton: Scott Segal. But in that ensuing years as the signs became more clear the industry through the global climate coalition and other organizations pursued large spending campaigns, creating doubt, taking a book from the tobacco playbook. So is there some responsibility or liability between what the companies knew internally and the doubt they were expressing publicly?

Scott Segal: Well, one thing I think you hear from the clip that you played is that policy choice is a very difficult and complex question. Exactly what to do is a difficult question. For example, if you choose a policy mechanism that is too inflexible or imposes too much cost, reduces the affordability or reliability of power, you may find that you have a public backlash on your hands that ends up with the repeal one step forward two steps backward So, you have to be careful in the direction you move.

Now I will tell you at the very time that there was a robust debate going on in Washington regarding what to do about climate change there was serially public policy being adopted along the way. So for example when the UN framework first came out the United States joined that with the acquiescence of the Congress and moved forward at that point. We did not end up endorsing the Kyoto protocol for reasons that had had more to do with whether all countries in the world would be equitably engaging and whether it would therefore be effective. But we adopted broad sweeping energy efficiency legislation that set up the basis of energy efficiency standards for appliances and buildings covering dozens of industrial sectors. We set up an inventory to measure what we were dealing with. We passed principal production tax credits for bringing new renewable power to market.

So all along the way we have made advances in the area of public policy until now for two of the last three years we’ve seen reductions in CO2 from the power sector. We've seen increase in improvements in the energy efficiency of automobiles. So all of that occurred as a result of not only market trends but also developments in public policy. A lot of times if you listen to what some in the advocacy community will say you think it's been a complete wasteland there's been nothing that's happened to advance the cause. And I guess the point I’m trying to make is know that it's been taken seriously, but it's been approached carefully and that’s what you've seen in the public policy area.

Ted Boutrous: Greg, I was just gonna jump in because kind of one of the things -- I wanna take head on the notion that I think the plaintiffs lawyers in a lot of climate change cases have been advocating is that the oil and gas companies were they had secret knowledge and they were then putting out misinformation and they try to analogize it to tobacco and other areas. It just it doesn't make any sense because and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals noted in a big case this Juliana case against the United States a couple weeks ago that it was well known. The federal government knew the problems of climate change the potential causes and knew that there was an issue here. And there was widespread discussion and in fact, in the San Francisco case that I've been handling we had a climate science tutorial that I presented at several scientists it was really a great experience I thought because we agreed on a lot of things. The judge said sounds like there’s a lot of agreement, and there was. And in that case, the lawyers had tried to make the argument that there was this secret misinformation campaign. And once they were in court the claim fell apart.

Some of the documents they were relying on were industry documents where industry officials were talking about and presenting the findings of the IPCC, the UN organization talking about what those findings were. So it wasn't secret knowledge, it was they were talking about the public knowledge. So this is a playbook that they're trying to adapt to climate change and it's really counterproductive because we are for example, I represent Chevron they accept the IPCC findings they don't do their own science. And so for a decade that's what they looked to. So I really just kind of want to debunk that point right out of the gate. We recognize there's an issue we have to deal with it everybody bears responsibility, all of us bear responsibility for going forward as to how we address the issue.

Greg Dalton: And that was I guess that sharing and distribution of responsibilities is one of the key questions, you know, everyone listening to this podcast and radio uses fossil fuels every day. And there’s a question of producer responsibility and consumer responsibility. And that's one of the issues that is being wrestled in court right now is what responsibility do the producers have. There's been studies that have shown that over the last decades, 25 producers account for just over half of the emissions of the last three decades, that the top hundred account for about 71% of this. And that’s just as industrial concentration, right, and a lot of those oil companies are from Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, India and some of them are Exxon and Pemex and China of course. So what is the industry responsibility for knowing the signs as you’ve acknowledged, Ted, what is the industry responsibility for the harm that we’re seeing now?

Ted Boutrous: Well, I think it really does affect it. It's very different than other circumstances where you've got some dangerous product that can be used in a way that can be harmful. Oil and gas, and I’ll just focus on those two products, are something we all need. And so it's not just the production it's the demand for it and it's something we need for hot water. We need it for transportation, almost everything we do, the screens on our phones depend on fossil fuel products. And so we are really all in this together.

I’ll just read you a passage from Judge Alsup's decision in the northern district the San Francisco case. He was balancing the potential harm versus the benefits and he said, “Without fossil fuels, virtually all of our monumental progress would've been impossible. All of us have benefited. Having reaped the benefit of that historic progress, would it really be fair to now ignore our own responsibility in the use of fossil fuels and place the blame for global warming on those who supplied what we demanded?” So it really is a situation where we’re all in this together. And from a legal perspective as Judge Alsup was pointing to there, it’s not legally appropriate, it makes no sense to really say it's those who are producing something that really contributed to the modern society, it's the way civilization is developed. And does that mean we shouldn’t all look around and say for example, Chevron, you know, it’s seeking to reduce its own carbon footprint. It's investing in innovative technologies. And I really think technology is going to be the key and things like carbon capture.

Greg Dalton: While lots of fossil fuel companies have acknowledged the scientific consensus and they say they support Paris. They've constrained competition, oil in particular has had a monopoly on transportation mobility for more than 100 years. Now electric is chipping away at that. Scott Segal. The companies say publicly we support Paris we recognize the science but in Washington, American Petroleum Institute and other groups do everything they can to prevent a price on carbon to prevent new entrants and competing fuels coming into the market. So they're trying to protect basically oil’s monopoly on mobility for aviation and automobile. So they're saying one thing publicly but in the policy realm they’re trying to prevent carbon pricing and new competition from other fuels.

Scott Segal: Well, you know, the first thing I'd say is that with respect to the fuel mix for automobiles in the United States today, actually the downstream of the oil industry that's the petroleum refiners have been the active participants bringing a new range whether that be advanced fuels, biofuels. In fact in the 2005 Energy Policy Act and the 2007 Energy Policy Act they were active negotiators on what the renewable fuels policy in the United States would look like. And so that has not been the situation --

Greg Dalton: It’s a lot of corn, right.

Scott Segal: Yeah. And believe me that's not my favorite product, right. But those that advocate in favor of biofuels have suggested that that is a way to address global climate change as well but there is controversy there.

Now with respect to electric automobiles, there isn’t just one energy industry in the United States. It may be true that the oil industry reflects at least some of where its own consumers are with respect to how free and available auto mobility can be and the significant benefits of the internal combustion engine. But on the other side of the spectrum the electric industry has been I know this will really shock you, no pun intended, has been a strong supporter of the introduction of electric vehicles. So, you know, industry is not a monolithic concept one way or the other. In addition, even in the oil sector there are companies that are now getting into the electric charging stations and doing what they do best, which is distributing the power that runs automobiles and trucks. And so if the fuel mix is going to turn more toward electricity I think we can anticipate that these companies will be involved in that market as well. They’re very innovative and that is their true history, innovation.

---

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about climate change and corporate responsibility. This is Climate One. Coming up, should carbon emissions be litigated, or regulated?

Scott Segal: One molecule of carbon dioxide emitted anywhere in the world is literally around the world within seven days, which both shows the incompatibility particularly of state court actions, but also shows the necessity of having a policy-based solution rather than a judicially concocted solution. [:20]

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. This conversation was recorded over the Internet with people in different places and times. We are doing that more and more these days to expand our reach, and cut our carbon impact. Climate One records many of our conversations with a live audience at our modern and green new home on the waterfront in San Francisco. When you are in town come I invite you to check us out. Our programs are open to the public and listed on climateone.org.

Let’s get back to my conversation about climate litigation, with Ted Boutrous of Gibson, Dunn and Crutcher, and Scott Segal, who represents energy companies at the Washington DC lobbying firm Bracewell.

A number of high-profile climate cases over the past decade, notably in New York, Baltimore and San Francisco, have been thrown out or gotten bogged down in legal wrangling over whether these decisions should be made at the state courts, federal courts, or in congress. Ted Boutrous gives us the backstory, and some context.

PROGRAM PART 3

Ted Boutrous: If we look back at the history there was a first wave of climate change litigation starting back in the early 2000s. And I mentioned the auto case that I was involved in. And the plaintiffs bringing those cases included governmental entities and they brought them in federal court. And the federal courts found that and it went all the way to the Supreme Court in the American Electric Power what we call the AEP case. In the U.S. Supreme Court in a decision authored by Justice Ginsburg said, global warming, climate change is a complex issue that involves science that involves economics that involves energy needs that involves the kind of things that federal courts just aren’t equipped to deal with. And that the Congress has delegated to the Environmental Protection Agency and therefore the Supreme Court held those claims could not go forward and they were nuisance claims. And in following nuisance law has never been applied to anything remotely like climate change. It started out as a tort for if, you know, someone was throwing garbage into your yard and it’s a very broad vague tort. But it's always been a much more micro cause of action.

So this has been a real swing for the fences for almost 20 years now trying to expand that tort. But the federal courts and the Supreme Court said those claims can't go forward. So fast forward about 10 year or eight years after the Supreme Court's ruling there was a the playbook changed and the idea was to go to state courts and make the same arguments under state law. We, in these cases that were brought, removed them to federal court saying that if anything these are cases that involve not activities in one state one neighborhood, even in just the United States. All the claims seek to regulate global activity oil and gas production all around the world and emissions all around the world. And the only courts that can deal with that and the only body of law you can look to is federal law; that's the source of the law. Then the question is, is there a cause of action. So we removed those cases. And Judge Alsup found that those cases should be in federal court. Couple of other courts have gone the other way. But whatever court they're in they are claims that cannot go forward because states don't have the power to regulate activities outside their own state. The plaintiffs recognize to their credit that their claims depend on all of the conduct. And you can't tell which emissions from where are causing what it’s everything together.

And so the courts simply cannot address these issues through litigation. These are policy issues our policymakers need to step up. You mentioned Congress and, you know, different groups and organizations and companies are gonna have different positions on issues and that admittedly are, you know, based on their shareholders needs in their companies. But the policymakers need to step up we all agree there's an issue here. Congress, the president, the other countries, we need to address this problem. But litigation like this is not going to be the ticket. And as I mentioned the Ninth Circuit in the Juliana case ruled where a public interest group and sued on behalf of young people said, these are problems. The federal government has known it’s undisputed for years, but a court can't tell Congress what to do or tell United States to stop using oil and gas and demand that there be laws enacted; that is for the policymaker. So that's why these cases are not gonna work.

Greg Dalton: And we’ll get to Congress in a minute. But first let me go as follow up with Ted Boutrous first about there is growing wave of opioid litigation and that is happening at state level as tobacco did. And is there any connection or concern about in the oil industry about what's happening in opioids, that that could prevent some difficult precedents for them.

Ted Boutrous: No, those cases really first they're really at the early stages. In the tobacco cases they did try nuisance theories and the nuisance theories and the cases never went anywhere. They were dismissed because the cause of action just doesn't fit. But the analogy doesn't hold up. Opioids and tobacco are completely different situation from the oil and gas industry. We’re talking about products in the fossil fuel area that are all of us use and need to exist in the modern world. They’re products that the federal government and the states encourage be produced. San Francisco and Oakland and New York and I handled the New York case as well. Our major users of fossil fuels, major contributors to the issue they're claiming is a nuisance. That's totally different than the opioid case, which is a more and those aren’t interstate international regulatory issues because you're talking about things that, you know, the opioid someone who was prescribed the drug and argues they were prescribed too much and they’re in a state. And the state can regulate what happens in its own state. Here, it's just this literally global issue being seek where you're seeking to try to regulate through a state nuisance cause of action which is light years away from even those more extraordinary efforts to expand nuisance law. So we don't think those analogies hold up at all.

Greg Dalton: And there’s something fundamentally different too. Tobacco, you smoke into your body, pills you put into your body. That’s very direct cause of action versus fossil fuels. The harm is literally globalized very different, although there some similar tactics and the companies’ sort of clouding science and some industry tactics are similar. The use of products is very different.

But I want to get to Scott Segal and the idea that policy leaders need to step up. You said that a lot of policy has happened the science which you both acknowledge will say that that policy is not enough in particular under the current administration that a lot of those regulations are going auto efficiency is going backwards from 5% annual fuel efficiency increased to now they’re proposing one point something percent annual increase. And there's a large influence of the fossil fuel industry in Congress that many would say is trying to slow down progress. So where's the policy gonna step up as Ted Boutrous just asked for?

Scott Segal: Right. Well, the first thing I want to do is agree on two important scores. First, this issue is an inherently international issue. One molecule of carbon dioxide emitted anywhere in the world is literally around the world within seven days which both shows the incompatibility particularly of state court actions but also shows the necessity of having a policy-based solution rather than a judicially concocted solution.

I guess I would also say that the worst of all worlds would be if the court sort of beat the Congress to the punch in addressing CO2 in a comprehensive way. Because if they did, we might have a patchwork quilt, we might have a failure to consider the economic consequences of exactly what would occur. The public health consequences of having an inadequate supply of affordable and reliable power. So no people don't want that. People might find it reassuring that the effort to address climate change in Congress may be is a little closer than we think that it is. There has been definitely a change in the way the public views this. I know we’re all familiar with polling data which indicates that 6 in 10 Americans are now either alarmed or concerned about global warming, even among Republican voters 7 to 10 Republican adults under the age of 45 regard climate change as the likely result of anthropogenic activity that needs to be addressed by public policy.

So there is this political consensus which has been missing; scientific consensus has been present. The political consensus is beginning to emerge in powerful ways. How can you test that hypothesis? Well, the house Republican leader, Kevin McCarthy just on the 12th of February announced a new set of policies which I think reflect an inflection point, even among the members of the Republican caucus of the necessity of dealing with comprehensive climate change solutions. He talks about advancing clean energy technology carbon sequestration making permanent tax credits to encourage the implantation of that technology. Enhancing plastics recycling, famously planting a trillion trees. All of these issues designed to address it. Are all of those going to be enough taken together? Perhaps not, but it’s certainly a good start and it shows the political salience of addressing climate change of both the Democratic and Republican side of the aisle. Look, in this Congress there have already been 306 bills introduced to deal with either methane or carbon dioxide or other forms of global climate change.

Just recently, the committee of substantive jurisdiction in the House of Representatives introduced a 622-page bill which it has about every mechanism, one can think of that would potentially -- with the exception of a carbon tax and that's for jurisdictional reasons -- that would address a global climate change. All of these things are moving faster than you would guess. You can say well it's a presidential election year it’s very hard to pass legislation during an election year. That's true. We regard from a Washington perspective the year 2020 is more of a table setting year but I believe dinner will be served in 2021 or 2022 as Congress begins to pick more and more going beyond merely incentives and research programs and into regulatory or quasi regulatory programs. So I think there's a lot more tumult around the policy choice now than there has been even in the very recent past. We've reached an inflection point in public policy.

Greg Dalton: Right. And it's just no longer tenable for Republicans to be in that place of it's not happening or we don't need to worry about it. But, Scott Segal, part of that, you know, the centerpiece of all that is a price on carbon. There's various proposals supported by George Shultz, Trent Lott a lot of Republican elders from the Senate putting a price on carbon but a liability shield has been one piece of that. The industry basically saying we’ll accept a future price but we want to be shielded from past consequences, accountability costs. So let's talk about the liability shield as part of a grand bargain which was I think that was part of the tobacco and perhaps others where it’s often industries price for participating is a liability shield.

Scott Segal: Right. Well, let's talk about that. If in the best of all worlds we would pick the most sensible, most cost-effective approach to dealing with global greenhouse gases. And that would be the congressional --- that would be the national policy of the United States. And mechanisms that are inconsistent with that policy would either be preempted or at least there would or either directly or indirectly. In other words, there are two different kinds of preemption. When Congress acts comprehensively to occupy the field then we are not supposed to also rely on common-law remedies that trod the same ground.

But sometimes as you've talked about there can be a direct form of preemption in the form of a liability shield. I have lived and worked in Washington for a long time and I will tell you there is very little chance of a liability shield being enacted. You talk about powerful horses from the regulated community who insist on liability shields. Well, brother I'll introduce you to some powerful forces on the other side called the trial bar which spends a lot more money actually in the political context than the energy industry does. I know that sounds crazy but it's true. And so I think the chances that we actually legislate a liability bar are low. However, God willing and the creek don't rise we will have comprehensive climate change legislation that will preempt the field having profound effects in both common-law remedies and state action. But if that happens, that'll be great for everybody because that will mean that we have adopted a very comprehensive approach to dealing with these emissions.

---

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining us we're talking with Scott Segal, a partner at Bracewell in Washington DC, which represents energy companies. And Ted Boutrous, who represents Chevron and other energy interests as an attorney.

I wanna go to our lightning round. First, this is a yes or no questions for our guest Ted Boutrous and Scott Segal. True or false. Ted Boutrous, in the past 10 years, there's been a big gap between what oil companies scientists knew about human clause climate change and what the company said publicly about it?

Ted Boutrous: False.

Greg Dalton: True or false. Ted Boutrous, Chevron underestimated the environmental liability of Texaco's operations in Ecuador when it acquired Texaco for $45 billion in 2000?

Ted Boutrous: False. I think that they underestimated the fact that there could be fraudulent litigation brought against them as the court in New York in the Second Circuit found. But I think the courts have helped resolve that by calling it a fraudulent extortion scheme.

Greg Dalton: True or false. Scott Segal, you are concerned about the eroding rule of law in the United States

Scott Segal: I think everyone should be concerned about the eroding rule of law in the United States. And it has nothing to do with climate change it has to do with other decisions some of which are in our executive branch

Greg Dalton: Which leads to Ted Boutrous. True or false. I’ve looked at your tweets you are concerned about active attacks on the rule of law by the Trump administration?

Ted Boutrous: That is absolutely true. I've been deeply troubled by those sorts of attacks, including attacks on judges, including interventions by the president with respect to what line prosecutors are doing. We’ve seen that just over the last couple of days attacks on freedom of speech and freedom of the press. So I’m very concerned and I think this is the time for citizens to rise up on all these issues and participate in our democracy and protect the rule of law.

Greg Dalton: Recently, I’m gonna bring this as we wrap this up, I wanna bring this down to kind of a personal level. I find this fascinating that Ted Boutrous, you're a lawyer defending the oil industry but you're concerned about the Trump administration, you’ve tweeted that our democracy is in trouble. And Scott Segal, you’re a former partner with Rudy Giuliani. He officiated your wedding, his first same-sex wedding. So I'm just interested in you two as personalities and people talking about, you know, how climate change will affect you and can our democracy right now solve something like climate change because you both said the courts are not the place, Congress is the place. It seems to be broken and it's run now by a climate denier and it doesn't look very good.

Scott Segal: I spoke a moment ago about how I think we’re reaching an inflection point politically. And I really do believe that and you’re really gonna think I'm crazy in a second when I tell you, irrespective of who’s elected in 2020 I think there will be a significant amount of pressure to take action on climate change. And once you remove the president from pressure from his right wing by reminding him that he can't be elected again, there you know, he might have some more maneuverability too. But just some data for people to take a look at. You know, Tom Steyer is running for president; he spent $126 million so far in advertising. Jay Inslee before he dropped out spent another 2 million. Mike Bloomberg said he’d spend a billion dollars. He’s spent 275 million so far and climate change is one of his key issues for framing up.

Why do I bring these statistics forward? Because it shows that the climate change issue is being framed as a front and center issue for political action. And that those dollars don't instantly fall away as soon as they're spent. It creates an impression it moves the needle and it has. The polling data has shown that and I think Republicans and Democrats alike know that they have to do something.

Greg Dalton: Ted Boutrous, your thoughts on Trump, oil and climate and democracy.

Ted Boutrous: Yeah, well, you know, it’s interesting I’m glad you asked that question. From a personal perspective, I really do think our democracy is in trouble and facing significant challenges. And I think the press has been extremely important in terms of scrutinizing what the president what the government is doing and companies. And I think companies need to engage with journalists and respond and be responsive and as transparent as they can be. And I think in terms of Republicans and Democrats, one thing the silver linings of this troubling time I think we've been going through is it has taught me that Democrats and Republicans who think about the issues, who really care about our country and our democracy, have a lot more in common than I ever would've guessed.

And so I've really, I tend to be from the Democratic side, but I'm, you know, sort of a centrist, but when I see the dialogue between really thoughtful people who disagree on a lot of policy issues. It makes me think we can come to solutions as long as we are able to preserve our institutions and they are under threat. So we are in a really serious time, both from climate change and issues like that but to solve those issues we need a strong democracy where citizens participate where we have vigorous press where you have a strong, three strong branches of government. So we’re at a really important moment here and I think, you know, I think we’re going to get through it and we’re gonna be stronger, but it's significant.

Music: In

Greg Dalton: You’ve been listening to Climate One. We’ve been talking about corporate responsibility and what’s ahead for climate policy. My guests were Ted Boutrous, a partner at Gibson, Dunn and Crutcher, who represents Chevron, and Scott Segal, a partner at Bracewell, Ann Carlson, Environmental Law Professor and co-Director of UCLA’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change & Environment, and Ellen Gilmer, Senior Legal Reporter with Bloomberg News

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast climateone.org. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or reviews.

Greg Dalton: Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Sara-Katherine Coxon is the strategy and content manager. The audio engineers are Mark Kirchner, Justin Norton, and Arnav Gupta. Anny Celsi edited the program. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, where our program originates. [pause] I’m Greg Dalton.