Greg Dalton: The 25th anniversary of the Goldman Environmental Prize, the most prominent award of its kind in the United States and perhaps the world. Each year, grassroots activists from six inhabited continental regions receive an award of $150,000 for courageously confronting powerful interests to protect our natural heritage. In the past 25 years, Goldman Prize winners have gone on to win a Nobel Peace Prize, taken up prominent positions in government, and continued their tireless advocacy. One prize winner in Nigeria was executed shortly after he received the honor. Over the next hour, we’ll look back at the award as a window into the last 25 years of environmentalism.

Joining our live audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, we’re pleased to have with us two members of the Goldman family and two award winners. Later in the hour, we’ll be joined by

Maria Gunnoe, an advocate in West Virginia working to clean up the coal industry. We also will hear from Kim Wasserman, an activist who helped shut down a coal-fired power plant in Chicago.

First, the Goldman family which I should note has a long history of financially supporting the Commonwealth Club.

John Goldman is president of the Goldman Environmental Foundation. His brother Doug is vice president of the Goldman Environmental Foundation. Please welcome them to the Commonwealth Club.

[Applause]

Thank you both for coming. So

John Goldman, tell us the context – the late 1980’s, your parents creating the Goldman Environmental Prize. What was that time like and what was the inspiration for founding the award?

John Goldman: Well, first, Greg, thank you so much for inviting us to the Commonwealth Club and Climate One. We deeply appreciate this opportunity to kick off our 25th anniversary. Our parents were lovers of nature from the very beginning. We often joked that my mom was a recycler before the term was ever coined. She was far ahead of her time. And our dad loved the outdoors, Yosemite, Lake Tahoe and locally a lot of time in Golden Gate Park. But he was also fascinated by awards, especially the Nobel Prize.

And there were two seminal moments that captured his attention. The first was in December of 1988, the Brazilian rubber tapper, Chico Mendes, was assassinated while he was trying to protect the rights of the indigenous people in the Amazon. And then three months later, we all remember the crude oil spill of the Exxon Valdez. And those two events sparked his drive to think about is there possibly anything that recognizes environmental activism. Is there anything that really raises these issues to the forefront? And so he sat down with our mom and our executive director at the time, Duane Silverstein, and said, “Let's look into this.” And lo and behold, there was nothing that was dedicated specifically to recognize environmental activists. And that was the beginning.

Greg Dalton: And your dad was a Republican which is pretty unusual. I mean, maybe these days it might be unusual but President Nixon founded the EPA not too long before that. So how did that play into it? Was that even a concern?

John Goldman: Well, we've often said that a Republican in San Francisco is a Democratic anywhere else [laughter]. But he was on the forefront, I think, of social issues. And again, because the world around us was so important to him, he felt that we should do something and could do something. So I don’t think it was a political affiliation that dictated anything. He was very proud of what we have around us.

Greg Dalton: Doug Goldman, what are some of the memorable impacts of the award over these last 25 years?

Douglas Goldman: I would say, to start with the most noteworthy impact, is the fact that this prize has survived for 25 years and continues to exist, to be better known than ever. Basically, we have been able to find people, often not even known in their own countries for the work that they're doing. Because of our methodology of getting nominations for prize winners and the whole process, the research that goes on, we find some outstanding individuals who’ve done incredible work, courageous work where they live that's making a difference. So in total, the work of these many people is, frankly, making a big difference locally and throughout the planet. There's a lot more to be done though.

Greg Dalton: What have been some of the challenges getting their stories out into the broader mainstream media?

Douglas Goldman: Well, we've been successful in getting the story in communities like the Bay Area where there's a lot of affinity for what we’re doing, a lot of interest. We find that the countries where the winners emanate from at a particular time, get a lot of publicity there. But to be really blunt about it, the East Coast media, we have a difficult time breaking into them, I think, in part because this is a positive story, this is heartwarming, the stories of accomplishment of the people, not necessarily what caused them to get involved, but what they have personally done and accomplished. And it may be because as human beings to survive, we have to be – when you go way back thousands of years, that we had to be aware of negative things going on in our environment to survive. And maybe that's produced today that people have a greater interest in negative things than positive ones when it comes to news.

Greg Dalton: Well, as journalists say, I'm a former journalist, they write about the planes that crashed, not the ones that land safely. So there's definitely an orientation in news in that direction. But a lot of this is a real – the stories are real David and Goliath stories. A lot of them – Doug Goldman, have been going up against the IMF, the World Bank. Is that strill the case or environmentalism shifted a little bit from that sort of one person against a big multilateral institution?

Douglas Goldman: Well, absolutely. What you're describing – World Bank, International Monetary Fund, these were institutions that played a very big role in a lot of big projects around the world going back 10-20-30 years.

However, a change has occurred in those organizations, and they become much more responsible when it comes to the environment so that now the prize winners that we’re dealing with often are going up against governments, often national governments, big corporations, multinational corporations. It is this big against little situation that they get involved with. But I think we’re very pleased to see that World Bank and IMF are not as prominent in being opposed by our winners as they used to be.

Greg Dalton: They’ve come around.

John Goldman, who are some of the most memorable winners? I'm asking you to pick, I know, some of your favorite children. Overall, what are some that really come to the forefront?

John Goldman: Well, Greg, I think there are some people that are very well-recognized, Wangari Maathai, Ken Saro-Wiwa,

Maria Gunnoe and

Kimberly Wasserman who are here tonight. But in thinking about the possibility that this might come up and looking at our list of winners, I think what was a common thread is there are individuals that we might highlight their personality whose force of nature really made a difference, their impact was significant, and they may have had significant personal risk. And so people like Jeton Anjain who was in the Marshall Islands, a stately gentleman who died shortly after receiving the prize in 1991. He led his people from his community away so that they would not be beset by radioactive fallout from our atomic bombing and testing. Dai Qing who led the fight against the Three Gorges Dam project issued a compilation of essays and was in prison for 10 months.

The dam was built but, as Doug mentioned about the IMF and the World Bank, that was a sea change as far as making a difference in how people of these large organizations and governments decided to change the way that they were looking at massive projects like this. There are host of others that I could go through. Ursula Sladek who brought up a community based energy consortium that has led the German government by the year 2050 to set a goal of 100% renewable energy. That's one instance of somebody who stepped forward and decide to make a world of difference for this country.

And then Azzam Alwash last year who had the amazing task of trying to restore the marshlands in Iraq that were destroyed by Saddam Hussein, and subsequently established the first national park in that country. These are just a few examples. There are so many other stories we could tell. They're all amazing heroes but those are the kinds of people that pop out.

Greg Dalton: One thing that caught my mind was Demetrio de Carvalho of East Timor, the world’s newest country that got into the constitution of that country, a right guaranteeing a healthy environment. So actually getting into the constitution is something that, I think, is interesting for other countries to get it as a constitutional right. Doug Goldman, what do you see as some of the progresses, some of the main milestones of the last 24 years, thinking about the stories or these people?

Douglas Goldman: I would say that in the world, there's much more awareness of the environment. We’re seeing young generation as being very aware, much more than those before them. People care more about the environment, there are more people who are doing things around the world to better it. But the fact of the matter is that the threats are greater as well.

Greg Dalton: And what are some of the primary threats right now thinking about the current time or looking forward? Is it water, climate change? What are some of the real overriding concerns?

Douglas Goldman: In my mind, the two most important things, climate change, clearly. It's a shame that politicians, especially in this country, have been fighting this issue instead of recognizing the dire threat that exists for future generations here and around the globe. At the same time, water issue is a huge one in many different ways. There is much of the world that doesn’t have safe drinking water to begin with. Climate change is going to result in rising water levels throughout the planet that's going to threaten marine wetlands as well as simply community, cities, are going to be in danger as a result of that. I think there's a great concern that we’re going to see conflicts in the future over water and water rights.

Greg Dalton: So what are some of the solutions to those things? You're an environmental philanthropist. What do you see as some of the solutions? Climate change is so big. It's hard to move that needle. Perhaps water – we have the drought in California. Perhaps – is there more – something more solvable there, more immediate in California on the drought?

Douglas Goldman: Well, obviously, conservation is a key. We are great consumers in this country. In the environmental movement, there's been recognition of the distinction between the north and the south. I'm talking about the globe. And that northern countries contain much more consumers.

I'm certainly guilty of that as are many others. We need to change what we do. At the same time, we do need – like our mother have done before, we have to recycle more. We have to find ways to not use as much and produce as much waste as we do. Reuse those things that we do use – find different ways of being consumers in our society. As far as the drought itself – we’re going to be faced with water rationing, most likely if it continues. We've been there before. We’ll be there again. And can we tell the world to not reproduce as much as they are?

Greg Dalton: That's the elephant in the room. A lot of environmentalists don’t like to talk about population. We can all drive Priuses, et cetera, but if there's 10 billion people, it puts a tremendous strain at 10 billion consumers who live like everyone in this room listening to this does. The world doesn’t have enough resources for that.

Greg Dalton: John Goldman, your thoughts on water, climate change, how serious it is. Are we going to rise to this challenge?

John Goldman: It's going to take a huge effort. I think that anything that we look at as far as a solution is all long term. We can do a lot short term to mitigate it. But you're right, the fact, as Doug mentioned, the population side is something that’s dictating our usage of all commodities.

Greg Dalton: And you used to run an insurance business. And so I'd like your insight on how people, to address climate change and clean energy, there's often a current cost to forgo something in the future. And we’re all about today and now and we don’t like current cost like all – I'll have my hamburger today and go to the gym tomorrow. That's tough to do for climate change, something that seems so slow moving.

John Goldman: Well, I think we’re all guilty and, unfortunately, our leaders in particular kicking the can down the road. And we don’t want to deal with what is here and now because a lot of times people think that the present issues are the most pressing. But there is a need to call to action, there really is, to address this. And the difficulty and the challenges are immense.

Greg Dalton: Is environmental action always bad for business? It's often seen as this tension, well, it's going to hurt jobs, we can't clean up the air, it's going to hurt jobs. It's either or, environment or economy.

John Goldman: I don’t really believe that, to be quite honest. I think that there is a way to have economic benefit as well as environmental stewardship. I think that the two can and should be combined, to be quite honest.

Greg Dalton: Doug Goldman, are some environmentalists righteous to the point that they turn people off?

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: None in this room, I'm sure.

Douglas Goldman: It's interesting there's a – I think historically, it's a movement that tends to be negative, the struggles are great. We’re dealing with people that some of the things they've had to overcome few of us would choose to take on. So it's very impressive but I think when your achievements are relatively slim, when the recognition is rare, you can easily become negative, depressed over the work that you're doing because after all, we all need some positive reinforcement for what we’re doing. So it has a tendency to do that. And unfortunately, when people feel they're up against it, it brings out the worst in people. And that's not the way we’re going to address the environmental issues of today and tomorrow.

Greg Dalton: And as stewards of the most prominent environmental prize, do you think about that, that this criticism from the environmentalism is being negativity, it's anti this and stop that and don’t do this? It's seen as a negativity sometimes. As stewards of the most important prize, do you look for that in the stories of people you're looking for?

Douglas Goldman: I think that the easy answer for us is the Goldman Environmental Prize. This is a very positive thing and we emphasize its positiveness. So by example, we’re showing something that's instructive to the world, individuals whom everyone can be extremely proud of their accomplishments, even amazed at times by their accomplishments but, in a collective way, honored by what they have achieved, and feel desire to be motivated by what they're doing and make a difference in that way. And that, I think, is a very positive way of looking at the environment.

Greg Dalton: So

John Goldman, how about the next 25 years, what's it look like? Where is the award going? Can you envision one day when maybe it doesn’t exist?

John Goldman: Well, ideally, it would be great if it didn’t exist because then our world community, our leaders and all of the people that inhabit this globe realize that stewardship of this planet is of utmost importance, and that we all take responsibility for insuring that such issues that Kimberly and Maria and others have supported and fought for don’t need to be fought for any longer. So that would be the ideal.

But realistically, we don’t think that's going to happen. So we’re hoping that this anniversary, while on the one hand, is a great opportunity to look backwards at all the accomplishments, it's more of a springboard for going forward. And our future is one where we hope that instead of celebrating these wonderful individuals once a year, that there can be a much stronger effort to have impact year round and on a continuous basis so that these stories and these individuals who reflect incredible compassion and commitment are known to more and more people and that the prize actually becomes much greater than just something that is well-recognized in the environmental world but is broadly recognized as something that represents the very best in people and the best in achievement.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about the 25

th anniversary of the Goldman Environmental Prize at the Commonwealth Club. Our guests are

John Goldman, president of the Goldman Environmental Foundation, and Doug Goldman, vice president of the Goldman Environmental Foundation. I'm Greg Dalton.

Before we go to audience questions,

John Goldman, I'd like to ask you if you could envision awarding a Goldman Prize to a business entrepreneur. And I ask that because a lot of young people these days, they look at environmentalism and they say – I'm thinking of the Method, the cleaning products company. I'm thinking of Mosaic, the solar crowdfunding company. Some people, and there are young people in the audience nodding right now, think that they can have as much impact on the environment by starting a business rather than a nonprofit that has to beg and raise money every year.

John Goldman: We have a restriction that exist right now that those who receive this prize don’t receive it for their full time occupation. This is something above and beyond what they would do or their grass roots initiative are things that they take on themselves and don’t expect to be rewarded for it or compensated for it. But that doesn’t mean that a business leader couldn't receive the award. And I believe that some actually have in their own way, that have done things that are beyond what their occupation is. So, of course, it could be anticipated that somebody would receive it.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about the 25

th anniversary of the Goldman Environmental Prize at the Commonwealth Club. Our guests are

John Goldman, president of the Goldman Environmental Foundation, and Doug Goldman, vice president of the Goldman Environmental Foundation. I'm Greg Dalton.

Let’s go to our audience questions. Welcome.

Male Participant 1: So, earlier you talked about corporations and their engagement with the environmental causes. And what I've witnessed is a lot of greenwashing which is a term that's already become popular and everybody knows it, about corporations that use it as a marketing ploy.

So isn't there really a return on investment when companies can get involved in either their community or on a broader scale, whatever their scope is, to either demonstrate how they're operating sustainably or more conservatively when it comes to the environment?

Douglas Goldman: Well, clearly that’s a problem. When was it? About three or four years ago, it suddenly became incredibly popular, not to pick any targets , NBC has a green logo on it, they have a week devoted to it. Did it make a difference? Hopefully it raised awareness. Companies do – usually I would say pretty small steps, but looking for big credit for that. I applaud the little steps but I'd like to see them make much bigger ones, much more serious ones.

I think one of the issues in it is that as more corporations do serious environmental work, the demand will go up. And therefore, the supply – by basic economics, that the cost of this will start going down. And that's usually what the objection is by corporations, that it’s too expensive to be environmentally sound. So the more that we can reverse that equation by more people participating, hopefully we will have the day where, for businesses, it's not the expensive choice, they don’t have to look at it in those terms. Look at what's happening in automobiles and gasoline. We’re looking at a shift because of the cost of gas.

And also we’re seeing electric vehicles and hybrids that are becoming more and more popular. Then a lot of people want to make that choice and others, it's starting to become a more practical economic choice.

John Goldman: I'm hoping that there is going to be more of an incentive. The problem with the EPA standards is that's all from our government and our leadership. It's not from the car companies themselves. They've been put into that position. So if there were an opportunity not to simply leverage being green but actually be green, that would be a major accomplishment.

Greg Dalton: I think buildings is one area where it's being driven by tenants and customers. Commercial buildings is an area where tenants want to be in lead building and lead, silver, platinum, et cetera, that's really a market driving it. Let's have our next question. Welcome.

Female Participant 1: Hi, Goldmans. I was watching TV recently on ABC News. They had a report and they were showing the incredible horrible smog in China and how they had to go like on a three-hour trip, the distance from New York to Boston, to actually find some air that they could see in and breath in. And I'm just curious, do you know of any people working to combat that in China who might be winning a Goldman Prize soon?

John Goldman: There's a gentleman named Ma Jun who has been mapping pollution for some time. A lot of his work has been on the water side but he's expanded it to the air quality as well. And he was just out here. I can tell from personal experience – I was in China in November of 2012. And with three days in Beijing, the smog got steadily worse until the Forbidden City was invisible from 100 yards away.

You couldn’t see the buildings at all. The thing that was, at least, comforting was when we left for Tokyo, you were rising out of this brown mass. And we landed in Tokyo and, of course, it was crystal clear. But it shows how important it is to address the fossil fuel issue especially in China with their consumption just going through the top. The Chinese government has made some indication of attention because the people are demanding it now more than anything else but whether that's going to have a long term impact with their meteoric growth, its going to be hard to see.

Greg Dalton: We had Orville Schell, the China-watcher here recently. And he said that they will solve that problem because the stability of the regime could be at stake. He's less clear though that they'll solve the climate problem but they'll clean up the air because we did it in Pittsburgh and we know how to do it. Let's have our next question. Welcome.

Male Participant 1: Hi. Thank you both for all the great work you're doing. In your opinion, what's the best way to get the general public in the United States and local governments moving towards renewable energy?

Greg Dalton: Who would like to tackle that one?

John Goldman: I don’t know if it's going to come from the public. I think, in some ways, it will come from the top down. And one of the major initiatives that is happening right now is something called Divest Invest which is to take investments in fossil fuel companies and remove them from the portfolios of foundations and individuals and redirect them over time to renewable energy sources. That is going to, if it does take hold, be a dramatic shift in policy because we all know that money talks.

Greg Dalton: And there's also risk, real risk to investors in holding those stocks in the future. Let's have our question. Welcome to Climate One.

Female Participant 1: Hi. So I wanted to address the question related to the World Bank and the role of the World Bank. And it was stated that role is much more positive these days. And I wanted to bring up the recent proposed Eskom project in South Africa which was to fund a very large coal-fired plant that the World Bank supported in the end despite activism to stop it.

And right now there is a situation in Kenya with an indigenous group called the Sengwer who are being forcibly evicted from their lands which essentially constitutes cultural genocide. And there's World Bank complicity and all of that. How do we deepen the conversation about the role of the World Bank and share a little bit more knowledge in depth about what's really going on.

Greg Dalton: We have just a minute left. Doug Goldman.

Douglas Goldman: Well, I don’t want to give the impression that they're perfect, that their environmental record today is outstanding but there's clearly been a shift, and I think that there are people working in the World Bank, in IMF, that care much more about the environment.

But it used to be that it was overwhelming how many of the individuals that we would read about in preparation for our prize jury meeting, how many individuals were taking on projects that were being funded by the World Bank and/or IMF. And we are not seeing it as extensive as it used to be. So I'm taking that as a positive sign that there is change. They still have a ways to go to produce the kind of record that environmentalists would be extremely proud of.

Greg Dalton: I'd like to end this segment by asking each of you something I ask most guests who sit here on the stage, and that is what are you personally doing to manage your own carbon and water footprint?

John Goldman.

John Goldman: Well, I think, first of all, our mother was a great example for us. And so I think that we are totally dedicated to recycling as much as we can. I can't say we are carbon neutral yet but we’re trying really hard in every capacity that we can. We do support organizations that are striving. We are very conscious of what we’re doing. And my wife and I have already committed to Divest Invest as a major step going forward, and hope that others will also follow.

Greg Dalton: Doug Goldman.

Douglas Goldman: And in addition to what John mentions, it is a struggle. I won't say that necessarily everyone in my family sees this the exact same way. But for a long time, to be very blunt, I could have driven a more expensive car, drove a Prius. And now Tesla, John does the same, in fact. In fact, I'm very excited about – it happens to be a marvelous car.

[Laughter]

And other ways trying to be conscious as much as possible about not being interested an out of control consumer.

Greg Dalton: We have to end it there. Our thanks to

John Goldman, president of the Goldman Environmental Foundation, and

Douglas Goldman, vice president of the Goldman Environmental Foundation. Thank you for coming in and talking with us today.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: We're joined now by two winners of the Goldman Environmental Prize.

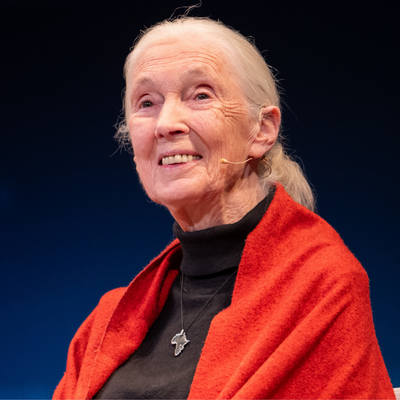

Maria Gunnoe is an organizer for a more environmentally friendly coal industry and an opponent of mountaintop removal. She's an organizer with the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition in West Virginia. She's a winner from 2009.

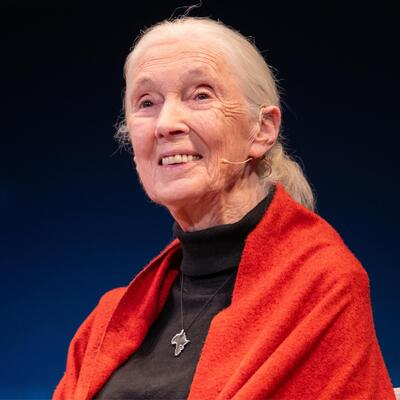

On the other side of the coal conveyor belt, Kim Wasserman, is an organizer that helped shut down a coal-fired power plant on Chicago's South Side. She's an organizer and director of strategy – organizing and strategy with the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization. She won her prize in 2013.

Please welcome them to the Commonwealth Club.

[Applause]

Being with you up here I got all tongue-tied and twisted it.

Maria Gunnoe, tell us about your land that's been in the family and how that got you into advocacy.

Maria Gunnoe: My land was purchased in 1951 by my grandfather. He passed on in 2001 and I gave him my word that I would oversee his land. Little did I know what I was saying. And my grandfather worked as an underground coal miner, and he worked and earned only $18 a week for a 40-hour week when he first started working. And he managed to work and pay for this 40 acres of property, and it's all been tended through the years. It's been taken care of in a way to where it takes care of our family. We have fruit trees and nut trees and a lot of medicinal herbs, and the mountains themselves take care of us and always have.

Greg Dalton: And there are springs on this land and how have the springs changed over time?

Maria Gunnoe: There are springs and then streams and also wells. We have wells on the land and this is our water resource, and over time since mountaintop removal began in the '70s, I have watched – I was born in '68, so I've watched as this happened. I've watched as they polluted our water, our surface water, our underground water and, most recently, our municipal water.

Greg Dalton: And so what got you into advocacy and how did you go from steward of this land and watching your streams change and how did you get into fighting the industry?

Maria Gunnoe: Well, I didn't really get into fighting the industry; the industry took me on. I tended to my family property. That's what I'd done. And in doing so, I realized in 2001? that I was going to have to fight mountaintop removal in order to protect this property and it just seemed like an astronomical task. And it has been. But, yeah, it – they took me on. They challenged me and my love for my property is what pushes me forward.

Greg Dalton: And were you threatened?

Greg Dalton: And what kind of security do you have at your home?

Maria Gunnoe: I live – I have 40 acres of property and I live inside of a 400 feet worth of chain-link fence, 6-foot tall. I have three guard dogs that live inside of the fence that watch over me, one that goes with me most times when I go somewhere; he goes with me. And I also have security cameras on all sides of my home. But it's necessary. There's times I feel like a prisoner in my own home, but at the same time, I'm still there and I'm still safe.

Greg Dalton: Because people threatened to burn you out.

Maria Gunnoe: Absolutely, they did. And my children overheard these threats. And my son was only 16, 17 years old and he was in the last years of school when he looks at me and says, "Mom, I can't go to sleep. I heard what they said at the football game. They're going to burn us out tonight." Well, that's when we realized that we're going to have to have security in here. I had went for two weeks with no sleep because I gave my son my word I would stay up at night and watch over things so that he could get the proper rest to get in school the next day. And after two weeks of that, we had to get guards to watch over my home to keep us safe.

Greg Dalton: Do you ever think of giving up?

Greg Dalton: Moving?

Greg Dalton: Do you think they knew who they were messing with?

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Kim Wasserman, your parents were activists and advocates. Tell us how you got into – your family background, how you came to advocacy.

Kim Wasserman: Both my parents are organizers and have always been, and we were raised going to marches and rallies and protests, and at a very young age, I decided that that was not going to be for me. I did not want to do that anymore. But I think both living in Little Village and then having my own family and feeling the impacts that countless parents in our community feel of having children with asthma just triggered that voice in me to want to understand why this was happening and want to do something about it. And I think there is no greater threat than a mom who's mad, to be quite honest with you, and it led me down a journey of 16 years now of organizing Little Village around environmental justice because I know that what I went through, I didn't want any other mom to have to go through. And so it became my life.

Greg Dalton: And how did you get the coal plant shut down in the south of Chicago? I just – South Side of Chicago, I think of Jim Croce, I think right – so how did you get that plant shut down?

Kim Wasserman: It took a very long time. I think that, as was mentioned by the Goldmans, a lot of what was very helpful was in the last 10 years kind of the greening of society, people talking about their carbon footprints, people understanding that the pollution from the coal power plant doesn't stop on Western Avenue because that's where our neighborhood stops. It goes all over the Chicagoland area. So I think people definitely started to understand that this was impacting them just like it was impacting us. And so it really took both that and I think the luck of having a change of administration in Chicago and actually having a mayor who understood what we were talking about and wanting to be supportive and help us get across that finish line to shut them down.

Greg Dalton: So was Mayor Daley not so supportive?

Kim Wasserman: No. You know, Chicago got a lot of acclaim for their climate action plan, and if you look at the plan, there was literally about seven sentences – seven words in the entire document that referred to the coal power plant, which is the largest single source of pollution in Chicago. Seven words to talk about that and so –

Greg Dalton: So a little bit of greenwashing in Chicago.

Kim Wasserman: Most definitely. [Laughter]

Greg Dalton: I like to talk about the jobs both of the people who worked at the plant and perhaps in the mines. What happened to the workers who worked in that coal plant?

Kim Wasserman: In our case in Chicago, actually out of the 100 and about 75 workers from both plants, none of them came from our neighborhood. They actually all came in from the suburbs or other neighborhoods, and so for us, there wasn't a direct job loss affecting our community, per se, but we were very much prepared for it. We reached out to the unions, we reached out to the workers really just to the talk about the exposure that they had working in these outdated coal power plants and to want to build solidarity with them and say, "Look, we're not trying to get you fired because we have nothing better to do with our time, right. This is really about your health and economic stability." Unfortunately, they did not see the benefit of working with us and so they went about what they did, and I believe it was a third retired, a third got bought out and a third got transferred to other plants across the state, unfortunately.

Greg Dalton: And,

Maria Gunnoe, your son works in the coal industry. So talk about the prospects for – I mean, if you were successful, mines will be shut down and men will lose their jobs.

Maria Gunnoe: Including my son. And just as a mother, I can't wait.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: To put your son out of work.

Maria Gunnoe: I love my son very much and I also – he is a hard worker and has never missed a day's work. He's a good employee. I also have two brothers that work in the coal mines. And he has learned the hard way that it's very necessary to be able to stand on your own and not depend on these companies for your life because you can't. I mean, it's not only environmental laws or regulation that shuts these companies down. When their bottom line drops, these men get laid off, period. In 1960, for instance, we had a 125,000 coal miners in the state of West Virginia. Now, we have less than 12,000 coal miners. And that's because of mechanization. That's not because of regulation. So like Kim, most of the workers that work on these mountaintop removal operations are not from our areas. Most of the men that mine coal that live in our communities work in underground mines and that's the traditional room and pillar mines where they go underneath the mountain; that's where my family – the men in my family work.

Greg Dalton: But where would they live? A job lost is a bad news for that family, and so what's the prospect either for your son or for other equipment operators, coal miners, if coal is on the decline – and we'll get to that in a little bit – where will the jobs for these people?

Kim Wasserman: Exactly.

Maria Gunnoe: Yeah. That's all they got to do is turn around their dozers.

[Laughter]

Kim Wasserman: That is exactly right. Exactly.

Greg Dalton: And in the case of your son, he's going to school and preparing for that day when you put him out of work?

Greg Dalton: And what's he studying.

Maria Gunnoe: Well, he's got his electrician license now. He's got – he's a certified emergency medical technician. He's got a lot of certifications that would make him employable in other fields.

Greg Dalton: And so Chicago, West Virginia, really two ends of the coal conveyor belt, very different cultures, urban America, Appalachia, yet there's something called Holler to the Hood where you actually – your organization, some others kind of went to each other's community to understand what the other end of the coal spectrum looks like. So we'd like to – Kim, do you want to tell us about that?

Kim Wasserman: Sure. So for us, it came about through meeting folks at the U.S. Social Forum in Atlanta and learning about mountaintop removal and coal extraction and meeting folks who talked about what it was like to live in the holler, what it was like to live next door to mountaintop removal. So it made sense for us to take a trip and take young people from our community and the hood to go down to the holler and understand what does mountaintop removal look like. And I think it was a real shifting point for our campaign to be able to talk about coal not just how it's affecting Chicago but how the life cycle of coal or the death cycle of coal, however you want to look at it, is affecting all of us. And so to be able to come back to Chicago and say, "Do you realize that we are not only killing people here, but we are also contributing to the deaths of people in West Virginia and any place that mining happens, extraction happens?" And for those young people to come to Chicago and see where their coal was coming to and to see how it was being used – I mean, how our community was being killed for a profit I think also brought that home for our young people. And so we continue to do that project every year. We continue to take young people from the holler to the hood. And I think it's a great way of showing that environmental impact doesn't just happen to any singular community. It's happening across the board to low-income people, and we need to be united and be coming together to fight this because that's what helped so much in our fight.

Greg Dalton: Maria Gunnoe, I'd like to get your take on that. I saw a video once where you said when someone in urban American flicks on a light switch, they are blowing up coal in your neighborhood.

Greg Dalton: So what was your insight from the Holler to the Hood program, meeting people from the other side?

Maria Gunnoe: Well, it connected the links for me and for many other people in our community, to see what mountaintop removal and coal mining was doing to people in our area, and I did – beginning with the miners. I mean, they live a very short life. Most of them don't live to see retirement. They live in very poor – they work in very poor conditions. And for us to see what was going on, it's sort of like watching a cancer eat away at a body. In our areas, you have mountaintop removal that is blowing up the mountains, polluting our air, destroying our water and then, lo and behold, they're carrying this coal to Kim's community and polluting her air and her water, and ruining the quality of life for people there. And it made the connection all the way into China. A lot of our coal goes overseas now. So basically, the coal industry is – they're spreading this cancer is, I believe, what we've discovered.

Greg Dalton: Coal use is down in America dramatically. It used to be over 50%. Now it's somewhere in the 30s, largely that's because of natural gas and there's a whole fracking conversation around that. But,

Maria Gunnoe, do you feel like you're winning in terms of trying to narrow the use of coal in the United States? Making progress.

Maria Gunnoe: I think, yes, we're making progress. We're definitely making progress. And fracking is not progress. Fracking has its own nightmares and water is our real true – we have to have water. We have to have air. If we don't have that, we die. Without electricity, we're not comfortable, which is more important? I mean, it's that simple.

Greg Dalton: But we may be exporting our coal to somewhere else.

Kim Wasserman: We are.

Maria Gunnoe: Yeah. Well, for instance, Mechel is a company and Essar are two companies – Mechel is from Russia and Essar is from India – they are in Appalachia. These companies are operating in Appalachia, blowing up mountains and polluting water, and taking every piece of the coal back to their country. In the case of India, they're taking it to India, they're making steel out of it, and then they're selling it back to us. So to me, it's a cycle of the dog chasing its tail, if you will. It just doesn't make sense. And, you know, human beings are being sacrificed for this. On one end of the spectrum, you have the government telling you that we have to do this for humans and it just doesn't make sense. It basically boils down to the fact that we're sacrificing part of the people in the United States to keep everyone else comfortable. That's just unsustainable.

Greg Dalton: Maria Gunnoe is an organizer with the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition. And our other guest today at the Commonwealth Club is Kim Wasserman, director of organizing and strategy with Little Village Environmental Justice Organization in Chicago. I'm Greg Dalton.

Maria Gunnoe, I'd like to ask you about the recent water contamination in West Virginia, lots of headlines around the country. It's affected you and your well. Tell us how that's affected you.

Maria Gunnoe: The municipal water in West Virginia – it's West Virginia-American Water Company – there was a chemical leak. The chemical was called MCHM. It's a chemical that's used to wash and prepare the coal and there was a leak, or a spill – or a release, however you want to call that.

It was 10,000 gallons of this chemical that was taken up by our municipal water. There were 300,000 people that lost water, period, don't use it, don't use it. You can only use it to flush. And it was an eye-opener for everyone, I believe, and most importantly, it risked the lives of 300,000 people. It was very, very poorly managed, all of it, from the time that they enacted the water ban to the time that they lifted it. The water ban currently is lifted, but the water is still not safe. There is still MCHM in our water. Our governor, after he proclaimed to not be a scientist, said that the water was fine, and that we should feel comfortable using and consuming this water again. But yet there's still a presence of MCHM in the water and it smells really bad. And our governor says, "You should drink the water, not smell it."

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: And so you have a well and you wanted to hook up to the municipal system. Are you going to now?

Maria Gunnoe: No. No. I called and told them actually that to not come back on my property. I didn't want their water.

Greg Dalton: And so people are getting by with bottled water?

Maria Gunnoe: Yes. Unfortunately. I mean – and we know that's not safe water either, but it's much safer than ours. And there is no safe water in the State of West Virginia. We've polluted – and keep in mind, water does not know boundaries. Where does this water stop?

Greg Dalton: Kim Wasserman, what's your community doing to get ready for the climate impacts, severe weather, climate readiness?

Kim Wasserman: A lot of what we're doing is trying to be proactive instead of reactive. I think, for us, one of the exciting things about the Goldman Prize and the acknowledgment of our work is it's able to show that we're not only really good at kicking butt, but we're also really good at planning. And as a community, we want to make sure that we're not only preparing, but we're doing it from a space that's culturally sensitive, that is local that really talks about what are the needs of our community and doesn't look at it necessarily just from a business perspective.

And so for us, it's a question of what are the impacts that are happening in Chicago. We've had one of the worst winters in Chicago. I left 20-degree weather to come to beautiful San Francisco. Record-breaking snow. And when you have 30-below days followed by 50-degree days two days later, the amount of flooding that happens and then it freezes again and then you have frozen water pipes.

So how is this impacting our community and then how are we advocating for the infrastructure changes that we need, and for us, it makes perfect sense. We need to rebuild our economy. We need to deal with climate change. Why aren't we putting our folks back to work to fix our infrastructure? Why aren't they fixing the bridges? Why aren't we fixing our streets? Why aren't we changing the plumbing? Those are spaces where we need jobs. Those are spaces where we need that work. And so for us, it's a question of how do we line ourselves up to advocate and be prepared for climate change but at the same time looking for the economic solutions that need to come along with that.

Greg Dalton: So it sounds you're rolling up health impacts, environmental impacts, job impacts which is – often our society is not very suited for dealing with things wholistically.

Kim Wasserman: Exactly.

Greg Dalton: Tell us about some of the improvements in your neighborhood, shut down this coal plant and now there's parks and other good things happening.

Kim Wasserman: So in line with the shutdown of the coal power plant, we were also able to advocate for the construction of a new 24-acre park which was desperately needed. They hadn't built a new park in our neighborhood in 75 years, and so we have a new park. And we also have a new bus line. We were able to advocate for better public transit in our community.

And so along with those improvements, we want more. We know that if it takes 15 years, we'll fight for 15 years, and we've done it. And so for us, it's really a question of how do we build off of that progress. Again, how do we become proactive in defining what is a sustainable community for us. I thought it was very interesting when you asked about the carbon footprint because that's actually a term that we don't use in our community because it doesn't apply to what folks are doing. Our folks are growing their own food. They are thinking about what they're consuming. They're thinking about the water and the plastic because it makes – it’s natural for folks to think about these things and not think about it from a carbon footprint space.

And so for us, a lot of the conversation on climate change, really we see it as separate from the clauses of climate change. What we want to do is bring those things together. All this money is going to prepare for climate resiliency and climate adaptation, but why aren't we making the link to what's happening in West Virginia and how that is making us have to prepare for climate change.

The fact that in the United States 300,000 people don't have access to clean water is astounding, yet we're willing to come after another country for violating the rights of some people and we can't even protect our own people here in the United States. And so for us, it's a question of how do we bridge our work but then also how do we prepare.

Greg Dalton: Maria Gunnoe, I'd like to ask you about EPA efforts to control emissions from coal-fired power plants. That's been in the news very much with the Obama administration. Where is that now and how is that affecting West Virginia coal?

Maria Gunnoe: There's less coal being sold to the United States by coal-fired power plants. Most of the coal now is going out of the United States and the coal-fired power plants have retrofitted their plants to use gas. And the coal market has failed tremendously. It's now 34% of our energy comes from coal.

And I think that's a good thing, considering a portion of the change has been renewable energy, but also gas and gas is not – it's not sustainable either. It's much like coal.

Greg Dalton: Could people put windmills on those mountains of Appalachia rather than blow them up?

Maria Gunnoe: Absolutely, they can. There is one mountain specifically, Coal River Mountain, there's 6.600 acres of wind-viable ridge lines there that coal companies want to blow up. And the people in the communities in Southern West Virginia are fighting to protect this mountain because it's our only chance of having renewable energy in the coal fields.

Greg Dalton: And windmills might be less destructive, but they're not going to provide the local jobs that a mine would.

Maria Gunnoe: Not long term, during the – and then, too, mining is temporary. It only takes approximately 7 to 10 years to blow up a mountain. That's not long enough to pay off a house loan. It's just barely enough time to pay off a car loan. So these are temporary jobs. It's not like you go into the mines and you're there for 10 generations. It don't happen like that. You have to move along and blow up another mountain to sustain those –

Kim Wasserman: Or move to another state like Illinois.

Greg Dalton: Our guests today at Climate One of the Commonwealth Club are

Maria Gunnoe with the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition and Kim Wasserman with the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization. I'm Greg Dalton.

Let's go to our audience questions. Welcome.

Josh: Hi. My name is Josh. And at my school, one of our teachers got cited in a tree for climbing the tree and they got a ticket for it. And so what I've noticed is that a lot of people are taking away our childhoods and they're pretty much destroying it, and it's kind of like taking – it's pretty much ripping out half of our body and we're not learning as much as we could from the environment. And so what would you do to get more kids to get into the environment and help out?

Greg Dalton: First, where did this person get cited for climbing a tree?

Josh: Here in San Francisco.

Greg Dalton: We're not responsible for San Francisco, [laughter] but we know it's a little strange that you come from West Virginia and Chicago, but how about getting kids involved? Who'd like to – Kim Wasserman?

Maria Gunnoe?

Maria Gunnoe: Well, I think that, number one, the future belongs to you, young man. And just like all of the younger generations in here, the future belongs to you. You make out of it what you want it to be. And anyone to be cited for climbing a tree has never – whoever done the citing has never climbed a tree.

[Laughter]

Kim Wasserman: And I think, for us, I think it's knowing that your voice, regardless of how old you are is important and to know that we are always – we see our young people eye to eye, whatever their age, they are no different. It's not an opinion; it's a fact. And so for us, every young person who comes to us and says, "I think we should do this," we do it. No idea is a bad idea and everybody should be respectful of young people and hear your voice and hear your message and carry that out because, as Maria said, you are our future, but you're also our now. And the more that you can get involved will hopefully lead to you staying involved for the rest of your life.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question.

Female Participant: Thank you both of you for your incredibly inspiring work. My question is for Maria. We got the news yesterday that Alpha Natural Resources, and this is the largest coal company that does mountaintop removal in West Virginia, they've just had a record fine imposed on them and as part of a $200 million settlement for water contamination. So my question is, is this a sign that organizations like the EPA are taking a stronger stance? Is this going to have an impact on communities like Bobwhite? And what needs to keep happening?

Female Participant: 200 million for cleanup and 25 million fine – 27 million fine.

Maria Gunnoe: Okay. Okay. Based – I feel like the EPA is – we've exposed the fact that the EPA is not doing their job around mountaintop removal and I feel like that they've been embarrassed into giving these citations and fining these companies. It's very blatant – the pollution in our area, the EPA has turned a blind eye to it for the past 15 years and we've humiliated the EPA into admitting that there's a problem and doing something about it, and that all started at the community level at grassroots. We visited with the EPA every year for, I don't know, at least 10 years.

Greg Dalton: Thinking about the electoral map perhaps. Kim Wasserman, anything to add to that?

Kim Wasserman: I wish I could say that our experience is different with EPA, but it's exactly the same. It's to get them to move on our Superfund site, to get them to move on the coal power plant, we had to embarrass them, we had to show that they were basically in bed with these companies.

And so for us, it's exactly the same thing. It's unfortunate because their job is to protect human health, but a lot of times it seems like we have to force their arm.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question. Welcome.

Female Participant: Hi. Thank you for both sharing your experiences tonight. I know that I could probably speak for a lot of us when I say that it's invigorating to hear your message and specifically the point that you have brought up several times about the global aspect of the power generation, coal and how energy is used throughout the world. I was wondering if either of you have gone abroad and taken your message in a cross-cultural context and worked with local community organizations, say, in China, for example, or with businesses or if you've really tried to stoke the fire of the grassroots movement on this elsewhere.

Kim Wasserman: Yeah. We were very fortunate last year to participate in a caravan to Mexico with Via Campesina which looked at how environmental impact is affecting all aspects of life.

And so it was a drive through Mexico to see both world and city life and to see rivers, like in Appalachia, that are white from polluting companies up river. To see folks who are dealing with mining issues in Central Mexico next to the Yucatan, it was amazing to know for our folks that their fight is not alone, that it's not just folks in West Virginia, folks in Chicago, that there's folks in Mexico, that there's folks in China, that there's folks all over the world battling the same thing. And I think what was the most compelling is that our stories – being that we were so many thousand miles apart, our stories were so similar, but I think what was the most amazing is that we still had governments that were ignoring the situation in Mexico, the situation in Appalachia, the situation in China, and saying, "It'll be different here. We'll have rules and regulations that'll make it safe. We'll be able to do things differently here." And it's like when do you stop that repeated cycle of the same thing and say, "No, it hasn't worked there, it hasn't worked here and it will not work here." And so when do we start to look at different ways of doing things versus continuing the same cycle over and over again? So we were very fortunate to be able to do that.

Greg Dalton: Maria Gunnoe, last word. What keeps you going? What fuels you to keep going in this fight?

Maria Gunnoe: Through most of my life, it was my children and now it's my grandsons. I just can't imagine it continuing to get worse, people that I care about, my grandsons' namely, will be here for that. And I would like to see my grandsons live in peace.

Greg Dalton: Will they stay on that land?

Greg Dalton: We have to end it there. Our thanks to

Maria Gunnoe who is an organizer with the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition and Goldman Environmental Prize winner from 2009, and Kim Wasserman, director of organizing and strategy with the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization and a Goldman Environmental Prize winner from 2013. I'm Greg Dalton. Thanks, you all, for coming today at Climate One.

[Applause]

[END]