The Enablers: The Firms Behind Fossil Fuel Falsehoods

Guests

Ben Franta

Christine Arena

Jamie Henn

Kathryn Lundstrom

Michaela Anang

Summary

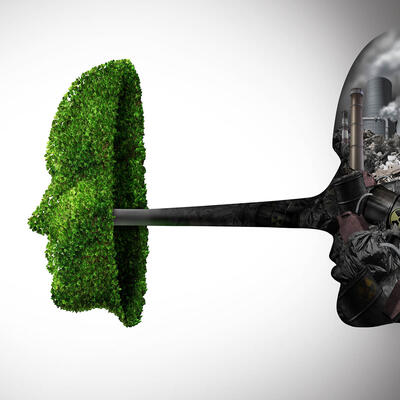

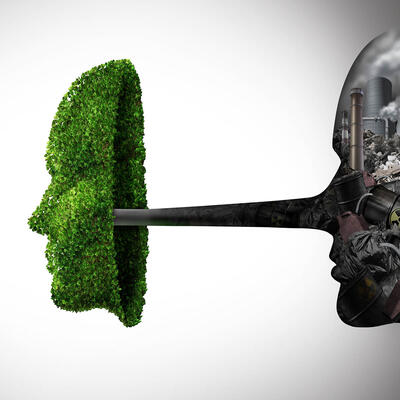

Public perception is important to any company, and fossil fuel companies are no different. Every year, they spend large amounts of money to make sure that the public is abundantly aware of all of the work fossil fuel companies are doing to help with the transition to clean energy. The problem is, the money spent on the messaging outpaces the money spent on the decarbonization.

PR firms, ad agencies, and law firms work behind the scenes to protect the fossil fuel industry and slow down the clean energy transition. Despite the industry having knowledge of the climate crisis as early as 1959, they continue to resist any change.

For example, many large oil and gas companies say they support a price on carbon pollution. Yet large oil companies invest a small fraction of their profits promoting carbon pricing policies and low carbon energy. The House oversight committee reports that less than half of 1% of their lobbying effort over the past decade focused on carbon pricing.The committee also reports that from 2010 to 2018, BP spent about 2% of its capital expenditures on low carbon investments. Exxon spent less than a quarter of 1% on cleaner energy. Jamie Henn, founder and director of Clean Creatives, gives some insight into these expenditures:

“I think it tells a story that big oil’s supposed commitment to climate action is little more than greenwashing. ExxonMobil just made record profits because of high gas prices. And what are they doing with it? They are telling their shareholders that they are going to increase oil and gas production, and they're doing a $10 billion stock buyback to reward their shareholders. In comparison ExxonMobil spent maybe upwards of about $300 million on algae research, which over the last 10 years, so that's about 30 million a year maybe. Yet that's the focus of all their advertising.”

Despite how much money these companies have to spend, they are still losing the battle of public perception. 60% of Americans say that fossil fuel companies are to blame for the climate crisis and about 50% of them want them to pay damages. Christina Arena, former VP at the global PR firm Edelman, argues that proponents of clean energy can use this reality to help deal with the climate crisis.

“This industry is kind of losing control of the narrative, even though it is trying so hard to direct it. And so, I think that opens the door for clean tech marketers and clean energy marketers to come in with a more compelling narrative. Tell your story better be more creative. Capture America's hearts and minds.”

Law firms also help fossil fuel companies' limit their legal liabilities. Michaela Anang, a research coordinator for Law Students for Climate Accountability and a law student at UC Davis, says the group grew out of a desire by law students to bring more scrutiny to their future employers.

“The top 100 law firms which we called the Vault 100 firms or Big Law are significantly contributing to furthering issues within our climate as opposed to mitigating those issues which we as students and as future legal professionals hope that they would be moving towards. ”

Related Links:

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: Many large corporations dedicate huge budgets to their image–selling the story they want the public to take in. Fossil fuel companies are some of the biggest spenders.

Jaime Henn: When you actually peel back the glossy advertisements and messaging from the industry, the real number showed that, practically, they're spending more on burnishing their image than they actually are changing their business plans.

Greg Dalton: Recently some law firms have come under fire, as well, for their work defending and representing fossil fuel companies. The next generation of law students want more accountability from the firms they may end up working for.

Michaela Anang: It's not that every law firm can drop a fossil fuel client overnight. But they can have these conversations and see that there is an ask and a need not just from law students, but from the communities that are being affected.

Greg Dalton: The Firms Pushing Fossil Fuel’s Falsehoods. Up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. For years, fossil fuel companies have claimed to support climate science and policy. Many have recently pledged to hit net zero emissions by midcentury. Yet behind the scenes they fight those very same policies, through industry associations, shadow groups, and lobbying. All while spending vast sums on advertising and PR campaigns touting their climate commitments. This week we’re looking at some of the entities that help these companies slow the transition away from fossil fuels, starting with public relations and law firms. Many of these groups are now facing their own pressure to drop their fossil fuel clients. First, let’s get some historical perspective. Climate One’s Ariana Brocious takes it from here.

Ariana Brocious: Dr. Benjamin Franta has a PhD in applied physics and is also a PHD candidate in history at Stanford. Through years of research, he and others have uncovered just how long fossil companies have known their products could hurt the climate–and how long they avoided telling anyone about it. Franta found one key example of this from more than 60 years ago in a Delaware archive.

Ben Franta: It was a speech given by Edward Teller, the famous physicist who worked on the hydrogen bomb, and he was giving a speech to an industry audience. It was a special conference put on by the American Petroleum Institute in 1959. And he warned them about the eventuality of global warming from fossil fuels and that that energy supply, that fossil fuels would have to be replaced.

Ariana Brocious: Franta says in the subsequent decades, the industry’s understanding of the climate impacts of fossil fuels only continued to grow.

Ben Franta: And by the early 1980s, the industry had a very sophisticated understanding of the issue. We now have internal reports from companies like Exxon from that time that predict very accurately how global warming would develop, many of the impacts and also had a clear understanding that the central problem causing it was fossil fuels and that fossil fuels would need to be replaced to stop the problem from developing. Around that time, I'm talking about the early 1980s even the late 1970s, scientists studying this problem and companies like Exxon were aware of the fact that if climate change was going to be avoided it was time to act then.

Ariana Brocious: This understanding wasn’t limited to U.S. companies, though some of them were leaders in hiding the facts. Instead of taking action on climate, companies did the opposite.

Ben Franta: Exxon deserves special mention because it had a quite advanced understanding of the issue and it was a leader in the industry in coordinating the whole industry's response to climate legislation and climate treaties. And in particular in trying to obstruct them and block them. In the mid-1980s Exxon informed many of the other oil companies about this issue, and essentially raised a red flag for them and said we’re going to be regulated as an industry because of this climate problem. And we as an industry need to be prepared and have a counter response ready to deal with climate legislation and climate treaties.

Ariana Brocious: Franta says throughout the 1980s, French company Total and others followed the strategies developed by Exxon to dispute and counter climate science.

Ben Franta: These included things like emphasizing the cost of climate action and deemphasizing the benefits of climate action and even distraction techniques which might surprise you things like emphasizing the need for reforestation or efficiency like these are things that alone would be good but they were deployed by the industry in order to distract attention away from fossil fuels. And they’ve been doing it ever since.

Ariana Brocious: In the late 90s and early 2000s, the industry started to reposition itself as integral to solving climate change.

Ben Franta: That's when the industry really began promoting things like carbon capture things like hydrogen and almost all hydrogen is made from natural gas is made from fossil fuel currently, at least. But basically, promoting industry friendly solutions to climate change that really you know have at least so far have not really been solutions but have continued to perpetuate the fossil fuel regime.

Ariana Brocious: Those tactics included shifting the blame to the public by popularizing the idea of an individual carbon footprint and personal sustainability.

Ben Franta: There are ad campaigns from the early 2000s that portray climate change as the fault of individual consumers and encourages them to do things like carpool more or change their light bulbs and portrays the fossil fuel companies as the leaders. And it was even worse because in reality those fossil fuel companies were not in fact taking the lead to address climate change. They weren't investing substantially in renewables, for example.

Ariana Brocious: Another frequent tactic of fossil fuel companies has been the use of so-called “advertorials” in major newspapers like the New York Times–often a full page ad written in the form of an op-ed.

Ben Franta: So, it’s made to look authoritative and neutral or objective but in reality, it's paid for by in this case a company like Exxon. And Exxon took these out you know for many, many years in the New York Times and used them to cast doubt on climate science but also to convince the public that climate action would be too expensive to undertake, that it would hurt the economy. And in fact, sometimes Exxon would cite studies by economists that said this, but those economists had actually been paid to do those studies by the oil industry. So, there's a lot of trickery involved and you know these were messages seen by huge numbers of people because they're in these, you know, very mainstream incredible authoritative newspapers like the New York Times. The New York Times still runs these sorts of ads for fossil fuel companies, and many of those ads still contain false and misleading statements like calling natural gas clean or exaggerating the amount of investment in renewables that the oil companies are making. And that of course skews all of our perceptions of what these companies are doing and, in a way, that New York Times stamp of approval on that ad it’s a form of the third-party technique. It's people who might not necessarily trust Exxon, but they might trust the New York Times and so they see it in the New York Times and they believe that message.

Ariana Brocious: These tactics–especially the economic arguments–have also been targeted at politicians, policy makers and business leaders.

Ben Franta: I saw then-President Trump give his announcement to pull the US out of the Paris Agreement. And to justify that he cited an economic study paid for by the industry and written by some of the very same economists who have been doing this for the industry since the 90s. And so, this strategy is still going on. It's still affecting public policy at the highest levels. And, you know, we need more oversight of that. We need to understand that whole phenomenon better, you know, because the future is at stake.

Ariana Brocious: In recent years, Franta says the fossil fuel industry has shifted to more greenwashing or climate washing techniques, often via social media.

Ben Franta: We see this all the time now with major oil companies. Exxon Mobil might be bragging about how much carbon capture it's doing, but if you actually run the numbers it's minuscule. So, they sort of specialize in giving a narrowly true fact that is presented in an overall misleading way. So, it's sort of a sin of omission or a sin of presentation.

Ariana Brocious: But there’s growing public awareness of this greenwashing, which Franta says is the first step in combatting it.

Ben Franta: Because if the public is aware of the trickery, then the trickery doesn't work as well. But also, this is unlawful, often, to deceive the public in this way about your company or about your products. And so, different parties can bring climate lawsuits that focus on greenwashing and try to put an end to it. And, you know, we’ve seen some suits like this in the United States and we’ve seen suits like this in other countries in Europe for example. And I think we’re gonna see a lot of these kinds of lawsuits as companies make climate pledges, as they try to green their images, as they make net zero commitments that might not actually have anything behind them. That's gonna be an important accountability mechanism to ensure that what these companies say they're doing or portraying themselves as doing, that they're actually doing that and not just not as trying to look good. So, it's a very, very important legal campaign, global in scope and the stakes are very high of course, because it’s going to affect the long, long-term future of the planet.

Greg Dalton: Dr. Benjamin Franta has a PhD in applied physics and is also a PhD candidate in history at Stanford University.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about those who enable fossil fuel companies to push misleading messaging about their role in the climate crisis. Our podcasts typically contain extra content beyond what’s heard on the radio. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods. Coming up, a former PR executive on the misleading messages from fossil fuel clients:

Christine Arena: They are advertising ideas that they're far more socially and environmentally responsible than they are in reality. Ideas that we can't live without them that it's dangerous to imagine a future free from fossil fuels and ideas that just generally confuse people about climate change and what the real solutions are.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about the firms that enable fossil fuel companies to maintain their social license to operate. I’ve invited three guests to weigh in: Christine Arena is a former Executive Vice President at Edelman and founder of the production company Generous Films, Katherine Lindstrom is Sustainability Editor at Adweek, and Jamie Henn is founder and director of Clean Creatives, a project for PR and ad professionals who want a safe climate future.

Companies spend a lot of money on advertising and messaging in order to appear more climate conscious. Exxon Mobil is the latest big oil company to announce that it aims to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. But Exxon's plans only cover Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, meaning it won't cover its biggest carbon impact: consumers burning the fossil fuel that it generates. Those are called Scope 3 emissions. I asked Christine Arena what she thinks about net zero pledges from fossil fuel producers.

Christine Arena: Oh, I think, you know, the fact that practically none of them to your point include Scope 3 emissions; they don't factor in the actual emissions generated when people use their products is a little bit deceptive. I think that at the very least, these marketers need to include the fine print so that people understand that Scope 1 and 2 emissions basically mean bringing fossil fuels to market more efficiently not decarbonizing our economy not scaling back on the emissions that scientists say we need to focus on.

Greg Dalton: Kathryn, how much advertising and PR money are companies putting towards this net zero and other climate-oriented campaigns? What’s the scale of the spend here?

Kathryn Lundstrom: That's a good question. I would love to know the specific numbers on this. But I haven't been able to dig that up. They’re pretty cagey, especially PR companies on how the money moves around. But I think the fact that these big PR firms are keeping oil and gas companies on their client roster despite a lot of really negative press, really bad PR for these PR companies. I think that shows that it's a big chunk of their revenue.

Greg Dalton: Many large oil and gas companies say they support a price on carbon pollution. Yet the House oversight committee reports that less than half of 1% of their lobbying effort over the past decade focused on carbon pricing.The committee also reports that from 2010 to 2018, BP spent about 2% of its capital expenditures or CapEx on low carbon investments. Exxon spent less than a quarter of 1% on cleaner energy. Large oil companies are spending pennies on carbon pricing policies and low carbon energy. I’ve asked executives in the past to specify their CapEx on renewables and they dance around the actual number. Jaime, what story do those numbers tell about capital expenditures and lobbying?

Jaime Henn: Well, I think it tells a story that big oil's supposed commitment to climate action is little more than greenwashing. ExxonMobil just made record profits because of high gas prices. And what are they doing with it? They are telling their shareholders that they are going to increase oil and gas production, and they're doing a $10 billion stock buyback to reward their shareholders. In comparison, ExxonMobil spent maybe upwards of about $300 million on algae research, which over the last 10 years, so that's about 30 million a year maybe. Yet that's the focus of all their advertising; it’s all about how they’re making fuel out of algae and things like that. So, again when you actually peel back the glossy advertisements and messaging from the industry the real number showed that practically they're spending more on burnishing their image than they actually are changing their business plans.

Greg Dalton: Kathryn, some high-profile podcasts like The Daily came under fire recently for oil company ads aired during the international climate summit in Glasgow touting the company's efforts for carbon capture, etc. There were questions about whether and how the New York Times fact checks those ads. It’s logical that these companies want to go reach popular influential audiences but what do you think about the trend toward moving to more advertising into newer media spaces?

Kathryn Lundstrom: I think it makes sense right from a strategy standpoint, you have a bunch of young people who may be a little bit skeptical of fossil fuel companies may be care more about the climate maybe are kind of hesitant to even start driving. Gen Zers aren't like driving at the same rate as previous generations. So, that's kind of a problem for oil and gas companies. They need to reach those folks and they need to advertise where those people are. It's just a question of whether those ads align with the policies of the platforms that are giving them space.

Greg Dalton: Christine, there's a line from a Guardian article about this that stands out. It says, “Oil companies almost never advertise their products, opting instead to advertise ideas, particularly the idea that they're working hard to address the climate crisis." Give us a sense of how PR firms work with fossil fuel clients on messaging and the relationship of their product versus making people feel they’re on the same side.

Christine Arena: Fossil fuel marketers are basically bombarding us with their messages doing very aggressive media buys across channels, right? So, if you have logged into Twitter, Facebook, the New York Times, Politico, or listened to a podcast recently. Chances are you've probably heard a fossil fuel ad, and really, if you look at the nature of those very, very pervasive ad messages you're right, they're not really selling us products. They are advertising ideas. They are advertising ideas that they're far more socially and environmentally responsible than they are in reality. Ideas that we can't live without them that it's dangerous to imagine a future free from fossil fuels and ideas that just generally confuse people about climate change and what the real solutions are. So, I think this is a very dangerous mix. This mix of misleading messages from fossil fuel marketers amplified so aggressively across media channels. This is a systemic issue, and it's an issue that is a serious problem because fossil fuel marketers aren’t restricted the same way tobacco or opioid marketers are. And they’re spending vast resources so their agency partners are turning around and creating these messages and programs and social and ad platforms are themselves not incentivized to police misinformation or police the problem. So, this is a systemic issue and to your question, you know, what is that role that PR partners play well, you know, they basically take the client’s money and execute messaging that fits the objective of that client. The objective of most fossil fuel ads is you know to do one of two things. Either you know it's not to transition us away from clean energy anytime soon. The agenda and the messaging are designed to keep the demands for fossil fuel products up and to avoid regulatory intervention and that's why they're trying so hard to influence public opinion and reaching out so aggressively.

Greg Dalton: And so, what is the possible avenue for regulatory intervention? Obviously, we have, you know, First Amendment, etc. regulating free speech very contentious. Is there a path for oversight by a government entity?

Christine Arena: There is, and if you look at opioids or tobacco, they provide models. Fossil fuel products kill 8.7 million people a year through pollution. If you compare those numbers to fatalities in tobacco, you know, tobacco products kill about 480,000 people year opioids death about I think deaths from opioids are at about 70,000 a year. So, why aren't fossil fuel marketers restricted in the same way that tobacco marketers are? There are clearly mechanisms for this level of intervention it just hasn't happened yet and that is partly thanks to the power of the fossil fuel lobby.

Greg Dalton: Jamie, you lead Clean Creatives that campaign pressuring public relations and advertising agencies to quit working with fossil fuel companies to spread climate disinformation. In January, your group joined with more than 450 scientists who signed a letter calling on advertising at PR agencies to drop their fossil fuel clients. What was the impact of what you’re trying to achieve?

Jaime Henn: Well, I think the impact of that letter really showed that this is a topic that PR and advertising agencies can no longer avoid. I think the role of PR in advertising in blocking climate action has been hiding in plain sight for years because it's the water we swim in every day. It's the messages, the advertisements that create the reality in the very language that we used to talk about the climate crisis. And as we've seen over the last few decades. These industries have played a huge role in blocking the type of conversation that we need to have about climate change and then the type of political action that could result from that. So, about a year ago my colleague and friend Duncan Meisel and I were looking out there and actually seeing all of this advertising out there that was flowing during the 2020 election and feeling like there had to be a way that we could begin to try and dismantle or at the very least throw a wrench into the gears of this propaganda machine. And so, we launched Clean Creatives as an effort to really go after the PR and ad agencies that work most closely with the fossil fuel industry. The idea being that Exxon Mobil, you know, their business plan really depends on selling oil but a firm like Edelman or WPP they can make money doing all sorts of things. They could work with sustainability-oriented clients. They can work with really big companies like GM which you know doesn't have a perfect track record, but is making the transition to electric vehicles and trying to move into this clean energy economy. So, the idea was that these were really essential agencies that were a part of the way the fossil fuel industry blocked progress but they were also movable targets who we could really bring onto the right side of this issue and tap into the incredible talent that exists in the creative sector. And instead of using that to destroy creation try and get those creatives to actually help address the climate crisis.

Greg Dalton: Well, Porter Novelli is a PR firm that dropped a client. Tell us that story.

Jaime Henn: Right. So, early on we were working with the writer Bill McKibben to put out kind of the first piece about the campaign that he was writing for the New Yorker and the case study that we were zeroing in on was the firm Porter Novelli which is a storied PR firm that dates back, you know, into the last century. And they’ve been working with the American Public Gas Association, which is the leading lobby group for the natural gas industry. And Porter Novelli had helped them develop a campaign called the gas genius which was targeting “woke millennials and Gen Z” and there was a lot of photos of people grilling fish tacos on their open gas flame and working with chef influencers on Instagram to talk about how they would only cook with natural gas. And we were gonna really take them to task for this campaign, you know, it had nothing about the risks of natural gas and methane emissions. Nothing about the health risks of having gas stoves in your homes, etc. And when we got in touch with them to kind of fact check the piece and talk to them about the issue they said, here, wait a second, well, give us a couple weeks and we’ll get back to you. And lo and behold to their credit, they came back and said, look we’re no longer gonna work with this gas association because “it is no longer compatible with our commitment to environmental justice.” And I think that was really telling both that they brought up the environment, but also social justice. We have seen a reckoning in the advertising space around Black Lives Matter around racial justice issues. We’re hoping that they extend that conversation to really look at climate justice and the climate crisis as well. Now, I’ll put a little caveat in the story and say that we’re not exactly sure that Porter Novelli has followed through on their commitment to not do any more work with fossil fuel clients. So, we’ll keep digging into that but it is a good sign that this campaign can move some really large firms and hopefully reshape the industry as a whole.

Greg Dalton: Kathryn, PR firms are hired to predict and create trends. Climate disruption is a trend that's accelerating. How much is fossil fuel a dividing line between the old guard and the new guard among people working in these agencies?

Kathryn Lundstrom: I mean, I think that it's only starting to become that. I think we talked a little bit already about that comparison to tobacco. And I think it works well in this one thinking about these PR and ad agencies because that really did become kind of a moral bellwether for agencies in the 90s. And I think since then, you know, like I mean I talked to one advertiser who worked at an ad agency, a really big ad agency in Chicago. And when she was hired, they asked her, it was her last round of interviews they asked her. Would you be willing to work on a tobacco account? And she had to like really you know struggle with herself, you know, eventually did say no, I wouldn't do that. They hired her anyways though and then they just her on different accounts. So, I think that kind, you know, that we're getting there with fossil fuels.

Greg Dalton: We hear elsewhere in this episode about an effort to in the law field to associate or disclose what law firms are doing business with fossil fuel companies and that’s very much targeted at law school students who are recruited by top firms and whether they want to work for firms that are representing fossil fuel companies coming out of law school. Christine, as a former VP at Edelman, how much do you think this kind of outside pressure has shifted their business model? In December, The New York Times reported on an internal meeting during which Edelman CEO Richard Edelman said the company would not walk away from fossil fuel clients, adding that Edelman services are needed by the energy industry as it transitions. So, what’s your response to that?

Christine Arena: Well, I didn't expect Edelman to walk away from very lucrative client contracts. I mean we know that between 2008 and 2018 Edelman did about half a billion, with worth of work for that’s just trade associations fossil fuel trade associations, including the American Petroleum Institute, the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers, National Mining Association and others. So, it is, you know, Edelman has different practices and the energy practice is extremely lucrative. So, I don't expect them to divest. But what I do expect is for them to continue to be a primary target for lawmakers and that's not just because of activist campaigns are my personal experience, but it's because there is real evidence showing how PR firms have played that central role in promoting misinformation on behalf of fossil fuel clients. I do suspect that that the focus and scrutiny on this industry will increase, not decrease. I am concerned that the industry is just really unwilling to acknowledge the core problem of misleading communications. PR firms just haven't wanted to talk about this despite the fact that there is an ongoing congressional investigation into climate disinformation. There are 13 active state AG lawsuits that center on that basis of misleading communications in advertising. And I just think that PR and ad firms are in a position where they're not only having to fight off activists but they're under some real scrutiny. So, I just think this is a conversation the industry needs to have much more openly and it needs to take actions to stop damaging potentially communities through misleading marketing communications.

Greg Dalton: We invited Edelman to join this discussion and they declined. Our invitation is still open and hope they’ll come on another time.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about those who work behind the scenes to enable fossil fuel companies. This is Climate One. Coming up, law firms also do a lot to protect fossil fuel companies, and slow the transition to clean energy.

Michaela Anang: The narrative that like everyone deserves representation and that fossil fuel industry deserves the, still deserves the best kind of representation. Why is that? Fossil fuel industry has so many resources.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Let’s get back to my conversation about PR agencies and the fossil fuel story with Kathryn Lundstrom, Sustainability Editor at Adweek. Jaime Henn, Founder of the Clean Creatives campaign. And Christine Arena, former Executive Vice President at Edelman. Chevron is hiring journalists to work in an internal “newsroom” to cover stories it doesn’t think mainstream outlets will write about. I asked Jamie Henn if it was possible that oil companies could bring these messaging functions in house and thus mitigate the need to work with outside PR firms or ad agencies.

Jaime Henn: Well, I think you are seeing that from a variety of different fossil fuel companies and throw concern. Chevron's been engaged in a fight for years over in Richmond, California, which is the largest point source, their refinery there is the largest point source of pollution in the entire state of California and had a devastating impact on the local community with their air pollution. And, yeah, Chevron started not only hired its own journalist, they started their entire own newspaper to try and put out their own spin on the news about local issues in Richmond. And of course, accompanied that with the major political campaign to try and take over the Richmond City Council. I think thanks to the work of grassroots communities there, activists and community members were really able to push back on that. And that is where the hope lies, I think that the fossil fuel industry when it tries to be so egregious to go so far to create their own newspaper or create their own content, they do tend to get called out on that. And I think people are a little bit sharper consumers these days and when they see stuff that looks so clearly like propaganda, they’re able to push back on that. And I think so examples like that are places where I think we’re able to try and make progress. I think the bigger risk is when actually a fossil fuel company isn't putting forward outright climate denial, but they're actually talking about solutions when they pretend to be our friend. That’s the harder stuff to really cut through. But ultimately, it's just as damaging because the goal of that content is to delay the type of public outrage and ultimately political pressure that could cause these companies to really change. And so, in some ways I'm less worried about Chevron coming out there and really pushing back on regulations. I'm more worried about them pretending that they are big fans of climate action when in fact they’re lobbying behind the scenes to block regulations everywhere from the local level all the way up to the international.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, these days everyone agrees on decarbonization and net zero; the debate is really about how fast. Whether it takes decades or centuries, or happen on the timeline that science wants.

Jaime Henn: I think that’s really critical because we've had the conversation with live advertisers who we've talked to about signing our pledge and they say hold on a second, we’re working with BP or Shell all about their climate solutions and how much they care about the issue. So, we’re helping the transition happen by putting out advertising from BP about how committed they are to climate action. And I think the thing to understand is that that is exactly the tactics that an industry under pressure would do, right. They want to act as if they’re solving the problem; they want to pretend as if they're making progress so that they won't face the type of pressure and regulations that would cause them to really change. And so, that advertising that “helping” is actually even more damaging. And I think that that's hard for people to hear because it is a beautiful ad about how committed BP is to climate action. But when only a few percentage points of their capital expenditures are going to clean energy and the rest is being poured into fossil fuels, that ultimately is false advertising and it should be called out as such, and ultimately regulated as such.

Greg Dalton: Let’s look to the other side. Christine, the clean energy sector is growing quickly, but it's a small amount and it’s fragmented compared to fossil fuels. They don't spend as much on advertising. They don't have the mega national consumer brands that happen that we know from the oil companies. Although car companies are starting to advertise EVs more, you know. Look at that side of it where is the power and the brand power and spending power on the clean side. Because ultimately these firms will move when there’s money to be made by these other clients.

Christine Arena: Well, yes, I mean, look, the fossil fuel industry is unique in that they have an exorbitant money to spend. it's just a huge industry and clean tech marketers can't match that scale at this level. But what they can do is command the narrative. Fossil fuel marketers even though their messages are so pervasive even though they're so aggressive about telling their story and trying to position themselves as part of the solution also are losing faith. People are losing faith in fossil fuel companies. We have about 60% of Americans right now saying that fossil fuel believing that fossil fuel companies are to blame for the climate crisis and about 50% of them want them to pay damages. And that's now I think that's only gonna increase. So, this industry is kind of losing control of the narrative, even though it is trying so hard to direct it. And so, I think that opens the door for clean tech marketers and clean energy marketers to come in with a more compelling narrative. Tell your story better; be more creative. Capture America's hearts and minds.

Greg Dalton: Jaime, how do you see the power dynamics there of this sort less mature, more fragmented, less wealthy clean energy sector, compared to these fossil giants who have been around and had 100 years to accumulate power and brand?

Jaime Henn: Well, I think Christine put it exactly right. I mean there’s no doubt that right now the oil and gas sector is dramatically outspending clean energy when it comes to PR and advertising. We did a report to launch the Clean Creatives campaign that looked at some data that we had available and this was between 2014 and 2018, which there’s a lag time because it's hard as Katherine mentioned to get this information from advertisers at certain points. But during that period what we could find, suggested that the fossil fuel industry had spent over $1 billion over the course of just five years to influence public opinion on these issues. And that outweighed the clean energy by a factor of 400 to 1. So, there’s just no competition between the two. That said, I think Christine is exactly right that this is changing and there's a few reasons why. One, everybody knows that this is where the future is headed. And if advertising and PR is about anything it’s about trends. It's about predicting the market, driving the market and everybody's clear that the market is moving away from fossil fuels to clean energy. Second, those are the companies that people want to work with. If you go to the main PR and advertising agencies around the country and around the world. Hardly any of them put their fossil fuel clients on their website. And if you're not proud enough to put your client on the website maybe you shouldn’t be working with them. This isn’t a work that people are happy about or proud about or that is attracting talent and winning awards it’s kind of the dirty secret that maybe keeps the lights on. So that's saying something about where the industry is going. And finally, it's not just clean energy companies that are part of this new economy or have something at stake in this conversation it’s also huge consumer facing brands that are trying to convince their consumers that they are committed to sustainability and wanna be part of a more sustainable economy. So, if I’m a brand like Unilever and I'm trying to convince my consumers that I care about the climate I care about the environment, do I really want to work with an advertising agency that is also working with Exxon Mobil to block climate action to put out propaganda about my product? That just increases the type of distrust that is destructive to brands. And so, I think that conversation is one that we’re really trying to have with major companies that might not be involved in clean energy but do have a stake in this conversation to say hey, just like you take a really close look at your supply chain to figure out whether or not the products you are sourcing are sustainable. Take a close look at your advertising firm and ask them if they're working with clients that are really aren't aligned with the mission and the values that you’re trying to put out there in the world. And I think that's beginning to happen. I think again this has been a sort of sector that's avoided the type of scrutiny perhaps not surprisingly, because they're very good at shaping public narrative. But it's something that's beginning to really take effect and I think in conversation that’s only going to expand in the years to come.

Greg Dalton: So, as we wrap up. What’s the next chapter in this Christine, what do you think the next term will be that you’re looking for trying to make happen?

Christine Arena: The next term is I think, you know, accountability. I think we’re seeing a wave of accountability journalism. I think we’re going to probably see some PR firms and executives specifically called as witnesses to testify at the oversight the House hearings on climate disinformation. I also think that we’ll probably see a lot of activity on the state level those lawsuits, the state lawsuits filed against oil firms for their deceptive advertising. I think that we’ll see some of the marketing partners named as defendants in some of those suits. And I think we're going to continue to see this wave of public interest and curiosity about this issue because climate change is something that everyone listening and everyone in the world is experiencing on some level.

Greg Dalton: Jaime, Martin Sorrell is like one of the gods of the advertising industry. He's made some moves recently. What is that told you about the way the winds are blowing in PR and marketing?

Jaime Henn: Well, I think it's a good sign and for those who don't know Martin Sorrell is one of the early kind of leaders and founders of WPP which has emerged as one of largest advertising firms in the world and he's now started a new company and one of the first steps he took was to sign the Amazon climate pledge and say that his agency was really going to focus on this. Since then, the details have been a little scant about what exactly that means. So, there's some accountability work that needs to be done there. But the point is that this is clearly where the market is headed. You are not gonna be an advertising agency in 2030 and not have a position on climate change. There is a parallel with big tobacco here, however imperfect. And I think people need to look at themselves and ask what I've been proud of working for Phillip Morris to block action to address cancer from cigarettes. You know what I wanted to have been on the account that put out the lies about that. And if the answer is no, then you better ask some serious questions about the work you're doing for the fossil fuel industry right now. Because the level of anger that people feel towards those companies today is only going to magnify as the impacts of climate change become more clear. We need those creative minds working for the good guys instead of putting out propaganda for Exxon.

Greg Dalton: We have to wrap it up there. Our thanks to Christine, Jamie and Kathryn. Thank you so much for coming on Climate One.

Christine Arena: Thanks for having us.

Jaime Henn: Thank you.

Kathryn Lundstrom: Thank you.

Greg Dalton: Law firms help fossil fuel companies' limit their legal liabilities, and they’ve also come under recent scrutiny for that work. The group Law Students for Climate Accountability grew out of a desire by law students to bring more scrutiny to their future employers – particularly those who shield the fossil fuel industry. They released their first climate scorecard in 2020. Ariana Brocious spoke with Michaela Anang, a research coordinator for Law Students for Climate Accountability and a law student at UC Davis.

Ariana Brocious: Your group released its second report in 2021 grading major law firms on their climate change work, and specifically looking at their litigation, lobbying and transaction work for clients. What were your key findings last year?

Michaela Anang: Well, they were quite similar to the previous year, which are that the top 100 law firms which we called the Vault 100 firms or Big Law are significantly contributing to furthering issues within our climate as opposed to mitigating those issues which we as students and as future legal professionals hope that they would be moving towards. So, our climate scores go from A to F, and also the potential for an A+ should a law firm take the climate pledge that we have as well as not represent any of the fossil fuel companies in the work that they do in transactions, lobbying or litigation. So far we don't have any of those on that list but we saw that because we changed our metrics just a bit to not have like a zero sum of renewable energy work canceling out the fossil fuel work that a lot of the firms who were performing maybe at a B level or a C level even moved down in rank.

Ariana Brocious: And so, how did you grade firms? You mentioned renewable energy work, not negating working for fossil fuel clients. What was the criteria that you used?

Michaela Anang: So, each of the scores so A to F has its own criteria for a grade. And for A scores across litigation transaction and lobbying we did factor in the renewable energy just so that we had something that could distinguish from a B score and below. But there had to be no cases or transactional work or lobbying for the fossil fuel industry and then a little bit of work for the renewable industry. For B cases or for B firms rather, there is no cases that either mitigate or exacerbate climate change so that is predominantly work for fossil fuel industries. And then C through F there’s a number range for litigation. It could be 1 to 2 cases, 3 to 7 cases depending on which letter grade. And for transactions it would be the dollar amount that they would be receiving from a firm and lobbying the same kind of metric.

Ariana Brocious: Firms are highly attuned to the values and preferences of graduates from top law schools who are their future leaders. So, how much of your intended impact is focused on that talent pipeline and sort of providing information to them?

Michaela Anang: I’d say a lot of it is focused on the students and we know that a lot of students have do have choice and others might be have less availability of options to choose whether they have financial barriers or they just don't have as much access. And that's something that we recognize and we don't want to feel like students should feel ashamed about their decisions. But they should be well-informed about them, right? And so, I think students are really trying to move in alignment with their values often but aren’t given the right information to do so. So, I think part of the intention of the scorecard is to say here is something that you should know when you're making these decisions. These law firms are complicit in these climate emergencies that we see daily.

Ariana Brocious: Beyond the responses from the firms themselves, what's been the impact of the report?

Michaela Anang: We’ve been heartened by folks who reached out, so, you know, really grateful for your outreach as well but just to kind of lift up this work. We know that structurally we're playing a role that we’ve seen in other areas, right, so like the banking sector and financing projects for the fossil fuel industry and who’s financing coal and fossil fuels or the advertising agencies saying more of a frontal callout. And so, we kind of just are nested in part of a larger ecosystem that’s trying to take away the social license of the fossil fuel industry. So, within that we’ve had outreach from particular firms. We've had outreach from students as well who are able to say I saw the scorecard and it was really helpful in me making decision or I saw the scorecard and I want to do something similar. I want to localize this information. I wanna know how I can kind of get an impact that I can reach the students at my school or I've been working with a particular community that was having an issue. How can we kind of leverage that. So, I think that's been huge. And then we've also had outreach from various organizations that we've been able to kind of try to learn from, and be in partnership with around the work that they're already doing about environmental justice in particular. And so, those are the kind of building and budding relationships that we want to continue to build so that we are better informed and positioned in like in right relationship with the work that’s already going on in so many areas.

Ariana Brocious: Will there always be smart and talented lawyers willing to defend polluters and oil companies as we see, you know, for other actors?

Michaela Anang: Yeah, that's the unfortunate thing that we just want to call to task honestly. Because what we've noted in the legal industry is that there tends to be this negating of responsibility, right? So, even the narrative that like everyone deserves representation and that fossil fuel industry deserves the, still deserves the best kind of representation. Why is that? Fossil fuel industry has so many resources? These big law firms have so many resources as well. We already know that they're highly well-paid, highly funded. And they are good at what they do, otherwise the same issues wouldn’t be continuing, right? So, I think that it should create a bit of pause to think we don't have to move in the same kinds of ways. There are other areas that again these big law firms will tell their pro bono work and say look how good we are in these particular areas but at the same time still continue to work with these fossil fuel industries that have so many resources and in-house lawyers often that they don't really need this kind of legal counsel that has a dozen big law firms within one set of litigation, right. This also is like serves kind of like an intimidation factor even against communities from being able to call out these industries. So, imagine being somebody who is being, who their community is being polluted by has negative impact of a fossil fuel industry and they know that these well-resourced law firms are gonna put their all behind the fossil fuel industry. How does a community move back, push back against that? A law firm has to think about those things.

Ariana Brocious: Michaela Anang is a research coordinator for Law Students for Climate Accountability and a law student at UC Davis. Thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Michaela Anang: Thanks so much for having me.

Greg Dalton: In developing this episode on professions that have promoted the fossil fuel narrative, I thought about academia. Are universities enabling fossil fuel companies to shape the story in a more subtle and less visible way than the PR firms we explore in this episode? Columbia and Stanford, for example, are starting interdisciplinary schools focused on climate and sustainability. That’s exciting because addressing the climate emergency calls for new holistic approaches drawing on all dimensions of our being and all parts of universities - chemistry, sociology, psychology, politics, communications. Climate changes everything we do and learn. But then I wondered how these two startup schools would be funded. Would they accept money from the very companies that for decades have spent huge amounts of money on delaying policies - such as a carbon price - researched and developed at America’s top universities? So I asked.

Columbia, my alma mater, referred me to its statement announcing its endowment would divest from fossil fuel stocks. The university didn’t respond to my question about program funding from oil and gas companies. Columbia’s energy program does list funders that include the world’s largest oil companies. Think about that for a minute. Columbia doesn’t want to profit from fossil fuel companies but it’s perfectly comfortable starting a climate school that runs on oil and gas money.

Several years ago, Stanford Professor Mark Jacobson said on Climate One that the university’s acceptance of $100 million from ExxonMobil in part compromised its energy research. In response to my recent query, a Stanford spokeswoman said the transition to net-zero carbon energy is expensive and will benefit from funding from energy companies. It added that energy companies can play an important role in scaling new solutions developed at Stanford. On the investment side, Stanford divested from coal around the time that most US coal companies were going bankrupt. And while Harvard, Dartmouth, Georgetown and other prestigious universities have committed to fully divesting their endowments from all fossil fuels, Stanford has yet to do so.

Corporate influence on campus is not confined to the energy industry. In 2003, Derek Bok, then president of Harvard, wrote Universities in the Marketplace: The Commercialization of Higher Education. He argued that universities are jeopardizing their fundamental mission in their eagerness to make money by agreeing to more and more compromises with basic academic values. I fear the stakes of that corrosion are even higher now as universities navigate away from fossil fuels to more sustainable, and just, ways of powering our economy. Lastly, it’s fair to admit that these issues are complicated and changing. Years ago, Climate One did accept funding from major oil companies. We no longer do.

Greg Dalton: Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe to our podcast on Apple or wherever you get your pods. Talking about climate can be hard-- but it’s critical to address the climate emergency. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation. Brad Marshland is our senior producer; our producers and audio editors are Ariana Brocious and Austin Colón. Our audio engineer is Arnav Gupta. Our team also includes Steve Fox and Tyler Reed. Our theme music was composed by George Young (and arranged by Matt Willcox). Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.